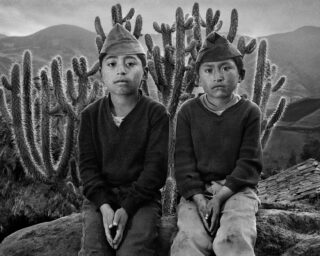

Martin Toft, Descendants of female members of the family of Te Utamate Tauri, also known as Mrs. Waetford, 2016

© the artist

Te Ahi Kā: The Fires of Occupation is a record of the Danish photographer Martin Toft’s time living with a Māori community in New Zealand in 1996, as well as his return twenty years later. Toft’s deep connection to the land and the community is largely a result of his participation in an illegal occupation of Mangapapapa, an ancestral land inside Whanganui National Park, in 1996. During this time, Toft was adopted into a Māori family. They even gave him a Māori name—Pouma Pokai-Whenua. But, as photographers and critics reckon with the medium’s colonial, often racist history when it comes to representing non-Western people, who can tell the story of a community? Do we really need another white man representing Indigenous life? I recently spoke with Toft to understand Te Ahi Kā against the backdrop of decolonization, climate change, and Māori spiritualism.

© the artist

Will Matsuda: I’m interested to know the origins of this project. How did it begin?

Martin Toft: I lived in Auckland in 1995 while backpacking around the world. In 1996, when I was twenty-five, I returned to New Zealand on the recommendation by my mentor, a Danish photographer and photobook collector. He suggested I should begin a project about the Māori. I was very young and naive and I had no connection to Māori. I also had very little knowledge of white men using photography to explore Indigenous cultures and I knew very little about New Zealand’s colonial history.

I ended up living in a Māori community for six months in the King Country, the central plateau of the north island of New Zealand. This is where the Whanganui River runs. The river is the border between three major tribes. I spent my first two months in this area speaking with people in the community and not taking any photographs. I realized that I needed to learn to speak the language to really present who I was, as well as explain my intentions.

I met a Māori elder who taught me how to deliver a formal speech to the tribe. And when I gave a speech the first time, the elders who were listening told me that they could see my ancestors behind me when I was speaking. I had never experienced anyone talking like this. I think they saw me as someone who had come from another place, but someone whose ancestors had been there before. That’s why they welcomed me into the community.

© the artist

Matsuda: And once you were part of the community, you became involved in their political actions as well?

Toft: After the initial ceremonies, I got integrated pretty seriously into the community. I took part in their occupation of a piece of ancestral land, Mangapapapa, deep inside Whanganui National Park, which surrounds the Whanganui River. It’s a very politically charged landscape. Many Māori tribes since the 1870s have been fighting the New Zealand government for ownership of this land and the river itself.

When the Europeans began colonizing New Zealand, they followed Western codes of land ownership; they began to portion off sections of the river and sold off pieces of land to new landowners. For the Māori, the river is a single living being, a whole thing. The tribes of Whanganui often refer to their river as an ancestor and talk about their river from the mountain to the sea. You cannot take one portion of the river, and seperate it from the rest.

In 2017, the government finally gave the customary rights and ownership of the river back to the Māori. Even more, the river has the same legal rights as a human. Before, if the Māori wanted to go fishing, travel by boat, establish a community, there were always legal disputes about how they could do this. With this new development in a settlement between the government and Whanganui tribes, it seemed a good time to return and finish the book. The book is about the time I spent with them in ’96, as well as my time there twenty years later, reestablishing the kinship that we had on a physical and spiritual level.

© the artist

Matsuda: The Whanganui River appears throughout the book. In a white, Western framework, we think of a portrait of a person and a landscape photograph as two very different things. But if you’re thinking about this river as a spiritual being, as an ancestor, how does that change the way you photograph it?

Toft: I traveled up and down the river on numerous occasions. It’s a major tourist destination, and I didn’t want to take the clichéd photos that everyone else was taking. I wanted the book to mimic what it’s like when you’re traveling the river. All you can see is water and the bush on the riverbanks. In the book you never see any images of the river from above. Instead, it’s dense and dark.

The river has 239 rapids and each one has a Māori name and story attached to it. For people who never have been there, it just looks like water. But for the Māori, they see the water and the rapid and it may inspire them to recite a poem or incantation. So I wanted to photograph these rapids for that reason.

But how do you photograph something that is not physical? I’m not sure if photography can do that and I’m certainly not claiming that I’ve done that. But I am interested in exploring how a photograph can have a third dimension, a spiritual dimension.

© the artist

Matsuda: This interview is published online in conjunction with the “Earth” issue of Aperture magazine. In the issue, Wanda Nanibush, a curator of Indigenous art at the Art Gallery of Ontario, argues that Indigenous people need what she calls “visual sovereignty”—the idea that native people should be the ones in control of their image. A lot of people question if we need another white man photographing an Indigenous community. I’m curious as to how you worked through this idea yourself.

Toft: It’s a very important question. As I said at the beginning, I was naive when I first arrived, but that doesn’t mean I didn’t have any respect for the culture. I arrived with an open mind and open heart wanting to learn from Māori and their unique way of life. In retrospect I think this naivete helped me make connections and form relationships, because I didn’t carry any historical burden that may have influenced my approach then. But of course now, twenty-some years later, having studied and gone to university, and teaching photography, I have a much better understanding of photography’s role in colonial history.

When I decided to finish the book, I did a lot of research about how Indigenous people in New Zealand had been photographed, especially in this particular region. In that research, I came across an expedition made by a white photographer in 1885, named Alfred Burton. His works now are held in national collections and some of his images are well-known within photographic history of that time, especially in the South Pacific regions. But he decided to go upriver, similar to me, to make photographs of the Māori at home. In 1921 there was another big ethnographic expedition to the river by a photographer named James Ingram McDonald, another white man. I wanted to make sure that the work that I produced recognized that history and context. I then began to think about how I could involve and collaborate with my Māori friends and family. I wanted them to have some creative ownership, and I wanted them to have input in the ways their images would be used.

Research in New Zealand archives was also an important element of the development of the book’s narrative and structure, and allowed images of ancestors from national collections to be seen by the descendants of those featured in nineteenth- and twentieth-century portraits. An important aspiration of the book is to reconnect people to their tribal treasures (taonga), and in the broadest sense to assist in wider reclamation of Māori knowledge, language, and customs.

Consultation to use the images was sought from living members of the Māori family, and permission was granted according to Māori taonga policies held in New Zealand museums, that acknowledge the guardianship (kaitiaki) and copyright of any Māori cultural treasures, including photographs that belong to tribes.

© the artist

Matsuda: How did you involve the Māori in the project?

Toft: When I returned to New Zealand in 2016, I took ten book dummies with me. I presented them to the tribe and explained to everyone, especially the elders, what my intentions were. I gave them the book dummies, which were more like family albums. It really showed the community and it was quite personal. It was far less abstract than the final book. So I wanted it to be a gift. Some of the people in those photographs from 1996 have since died, so I knew the photos would be valuable to the tribe.

I wanted to make sure that I had their permission to continue. This was partially what the trip was for, but it was also to make new work, now that I had much more background knowledge about my position as a photographer from outside the community. This time the images were mainly of the natural landscape. There were very few portraits.

After I transcribed all the interviews, I checked with members of the tribe to make sure that they made sense and that the information was correct. I wanted to make sure they were happy with the narrative.

Another reason I returned after twenty years was to ask why they had given me a Māori name, Pouma Pokai-Whenua. What exactly did that mean for them? This book also explores what it means for me.

But of course, I totally understand what your question is. I’m not trying to shy away from it; I still understand my position in the sense that they haven’t made the images, although in some of the images we collaborated on how we set them up, and how they posed. But essentially it is my interpretation. And, of course, I am a big advocate for Māori people themselves to be their own visual storytellers.

© the artist

Matsuda: I want to return to your Māori name. I think that gesture is key to this work. In one of the interviews about this in the book, you say, “I was young then and I didn’t fully understand the honour that was bestowed upon me. It is something that brought me back here 20 years later because I knew you had given me this privilege of being allowed to make these images. I do feel that there is a sense of responsibility to do something with this before I pass on.” Can you describe that responsibility? Is this book the “something”?

Toft: The group that I lived with was known in the area as being very politically active. They had been doing protests before, had been on television, and people had read about them in national media. I didn’t go there specifically to get involved politically with them, but that’s what ended up happening.

After I became accepted into the community, I was given the responsibility to talk to the media. It sounds very strange now. They knew that by doing the protests, and illegally occupying the land in the national park, that the media would be there. And of course they were. I was given the task to facilitate and mediate that side of things, while other members of the tribe had other responsibilities. It was my responsibility to make sure the story was handled in a proper way. I told them from the very beginning, even in the first formal meeting that I had with them, that I wanted to make a book.

I left in ’96, due to visa complications. My family (whānau) believe in Māori sovereignty and self-determination (tino rangatiratanga) and did not recognize the authority of the New Zealand immigration authorities. I persuaded them to not go forward with a legal challenge, and so I had to leave the country. And when I left, they told me that they trusted me entirely to use the material how I see fit. That was a very big responsibility that they gave me—to look after these photographs and stories of the community. I went back in 2016 to make sure that they still felt this way.

© the artist

Matsuda: Now that the book is out, what are your hopes for it and the stories it contains?

Toft: I hope that this book is used within the community as a resource for future generations about what happened during the occupation in ’96. Those protests have now changed the law. The rights to the river have been given back to the people. There are still many claims on the land that surround the river, and those are now in the process of being settled too between Māori people and the New Zealand government.

I want this book to be part of that story. The book first and foremost is for them. I am, of course, not denying that it is for myself, too. But I am more interested in how it is received by them, and the wider Māori community, more than anything else. It’s great that a place like Aperture will write about it, or that the book will go to Paris Photo, but it’s for the Māori, first and foremost.

Right now we live in a world where the biggest issue is climate change and the environment. As Westerners, we have destroyed the natural world. We can learn so much from Indigenous communities, not just the Māori, about their relationship with the natural world. I hope we listen.

Te Ahi Kā was published by Dewi Lewis in 2018.