On Remote Sites of War by Diana C. Stoll

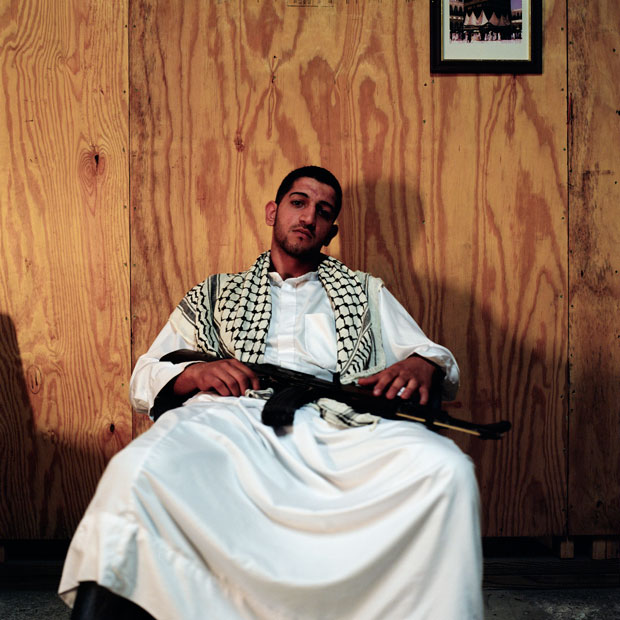

Todd Drake, from Looking In, from the Double Vision: Perspectives from Palestine series, 2013. Courtesy the artist

In June 2014, as Barack Obama readies to deploy a team of “military advisors” to Iraq, Americans have reason to reflect, yet again, on how distant this conflict and our ongoing war in Afghanistan seem to many of us here at home. The numbness (is it really inevitable?) that dulls our consciousness with regard to news and images of violent atrocities—from wars overseas to shooting rampages at home—is all too familiar, and yet remains beyond comprehension. The exhibition Remote Sites of War, at Western Carolina University’s Fine Art Museum, brings us into the mind of conflict from several oblique angles, looking for ways to puncture the stupor. The show, curated by David J. Brown (the museum’s director), features three protagonists: artist Skip Rohde, and photographers Todd Drake and Christopher Sims.

Skip Rohde, Consultation, from the series Faces of Afghanistan, 2012 (ink on paper). Courtesy the artist

Rohde, a Navy veteran, worked as a consultant with the U.S. State Department in Afghanistan’s Kandahar Province from 2011 to 2012, helping to bolster “Afghan capabilities” in terms of both security and governance. His job required that he attend many shuras—gatherings of Afghan officials and tribal leaders—where he took the opportunity to sketch portraits of attendees. More than fifty of Rhode’s rather classical pen-and-ink and pastel drawings from Afghanistan (and some from Iraq, where he lived from 2008 to 2010) are hung salon-style here, offering an unusual glimpse into the specific human dimension of places we tend to understand largely in terms of statistics.

Todd Drake presents Double Vision: Perspectives from Palestine, which was created in the West Bank and East Jerusalem over the course of three weeks in 2013. In recent years, Drake has traveled and conducted photography workshops in Saudi Arabia and Bahrain; like those trips, his visit to Palestine was at the invitation of the U.S. State Department. The project is in two parts: “Looking In” (photographs by Drake); and “Looking Out” (images by young Palestinians with whom Drake held workshops). “Looking Out” follows in the steps of Wendy Ewald, Eric Gottesman, Zana Briski, and others who have worked with young people in underrepresented communities around the world with a view to “empowering” them with the capability of generating their own photographic narratives (though the practical agency of that power is not always clear).

Here, the resulting images are mixed, of course—some are plainly youthful attempts at polished commercial-style work; others are more raw and more intriguing. Several are accompanied by impassioned texts, as for example Yara’s image of a young child and a birthday cake topped with fireworks, with a poem/declamation about the life of a Palestinian girl living under occupation: “I will keep resisting,” Yara writes. “And resisting/And resisting.” As for “Looking In,” Drake’s images of barbed wire, Israeli settlements, the separation wall, and checkpoints belie the ingenuousness of his statement: “To be in Palestine is to walk inside two visions: that of Zionists seeking a place to come home to, the other of Palestinians seeking to keep olive trees and stones they can call their own, their pasts, presents, and futures seeming to run along parallel tracks.” And yet, as irresolute as Drake’s stated position is, it may be as good a summation as any of the intractable loggerheads of that region: Israel and Palestine have far to go on their “parallel tracks.”

Christopher Sims, Richmond International Raceway, Richmond, Virginia #1, , from the series Hearts and Minds, 2008. Courtesy the artist

The three photo-projects by Christopher Sims in this exhibition take us in directions that are more complex and less trodden. Hearts and Minds is an unsettling look at young people (all boys, as represented here) at a U.S.-military-administered traveling recruitment event known as the Virtual Army Experience. Here, inside massive tents set up at amusement parks, state fairs, and NASCAR races, participants can play virtual-soldier games and engage with other forms of “militainment.” As Sims notes: “The army reveals itself to be a keen reader of American adolescent emotions and passions, and employs this understanding through a brilliantly designed and bloodless simulation of the thrill of the fight.” Indeed, the young men in these photographs are aflush with the intensity of the moment—the fun of it—reminding us of journalist Chris Hedges’s chilling observation that “the rush of battle is often a potent and lethal addiction.”

Far calmer—and disturbing as such—is Sims’s series of images from Guantánamo Bay, where he traveled in 2006 (after more than two years wrangling for U.S. government clearance). Under rigid military restrictions about what could be photographed at Gitmo—no aircraft, no radio domes, no faces of prisoners, etc.—Sims shot scenes that are quite intentionally action-free: worn playground structures, an empty café, desk chairs in anonymous, fluorescent-lit offices. These images serve as an ominous basso continuo, bracing the unknown activities taking place in detention camps just around the corner.

Christopher Sims, Iman’s Bodyguard, Camp Mackall, North Carolina, from the series Theater of War, 2006. Courtesy of the artist.

Finally, Sims’s Theater of War: The Pretend Villages of Iraq and Afghanistan brings us into mock worlds set up within the training grounds of U.S. Army bases in North Carolina, Louisiana, and California. Here, in the pretend tumult of pretend countries (“Talatha,” “Braggistan”), U.S. soldiers can (sort of) see how it feels to interact with people in the Middle Eastern territories with which the United States is engaged. In these staged environments, the “villagers” are often played by recent immigrants from Iraq and Afghanistan—and Sims himself sometimes plays the part of a “war photographer” in these non-wars. While Sims’s photographs inevitably bring to mind the images of war simulations by An-my Lê and Richard Barnes, here we are in full color and full disclosure: there is nothing convincing about these bizarre games.

A former photo archivist at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, Sims knows something about the many ways images interact with the monstrous fact of violence. Of his Guantánamo project, he has said: “I became interested in the idea of making war photographs that . . . weren’t about seeing violence, or spectacle, or the things that make people turn away from most war photographs. I began thinking that maybe the thing to do was to try to make a type of war photograph that captured something else.”

In a sense, this is the challenge taken up in each of the projects in Remote Sites of War: they are sneak attacks, intended to poke at, and perhaps reawaken, our exhausted cultural psyches.

_____

Remote Sites of War was presented at the Fine Art Museum, Western Carolina University, Cullowhee, North Carolina, April 10–May 30, 2014.

Diana C. Stoll is a writer and editor based in Asheville, North Carolina.