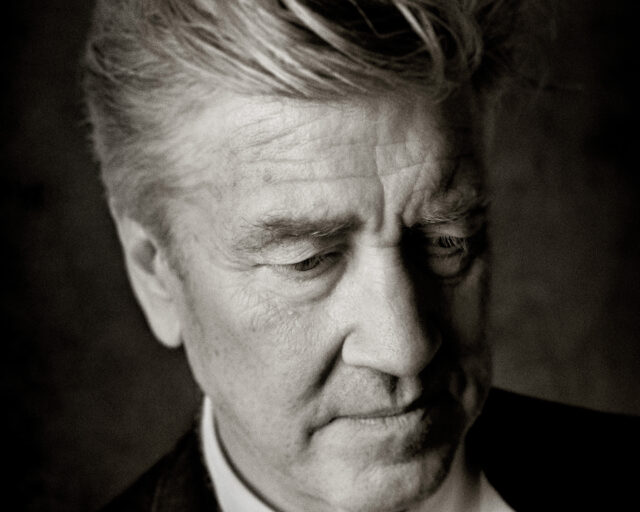

12 Photographers on How They Conceptualize Their Work

What comes first for you: the idea for a project, or individual photographs that suggest a concept?

Todd Hido, #2479-a, 1999, from House Hunting, 2001

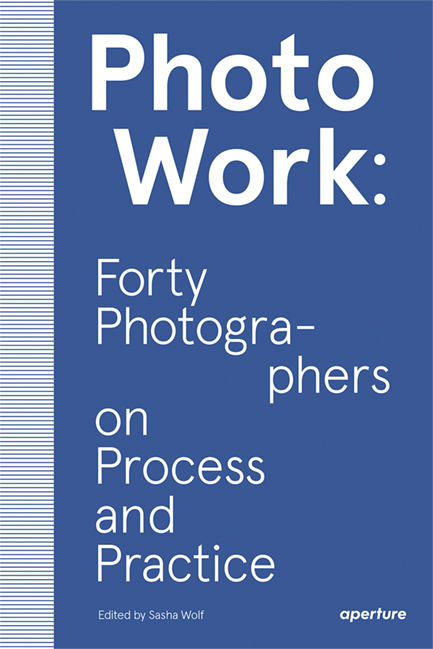

Over the course of her career, curator and lecturer Sasha Wolf has heard countless young photographers say they often feel adrift in their own practices, wondering if they are doing it the “right” way. She was inspired to seek insight from a wide range of photographers about their approaches to making photographs, and, more important, a sustained body of work. Their responses are compiled in PhotoWork: Forty Photographers on Process and Practice. Below, twelve artists respond to the first question in the interview series:

What comes first for you: the idea for a project, or individual photographs that suggest a concept?

Courtesy the artist

Robert Adams

Thinking up a project and then making pictures that fit does not, in my experience, usually result in the best pictures. Most of the books I’ve published have started with just walking and photographing, free of any plan.

Courtesy the artist

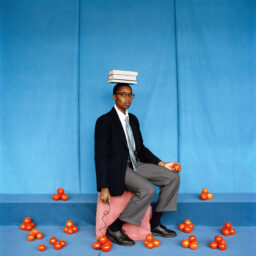

Dawoud Bey

My work always begins with an idea, with something that I need to talk about. I make my photographs in order to provoke a conversation around things that I am invested in. The challenge is how to give those concerns a resonant and coherent form so that the viewer becomes interested and invested. I want the things that matter to me to matter to the viewer.

Courtesy the artist

Elinor Carucci

Somehow both things are happening: I can have an idea for a project and then take individual pictures that will lead me to change the project. Many times I will take pictures that I think are about one thing, but they end up being about another thing—then I listen to my own pictures and understand what my project is about. At that point, I have the idea for a project that I follow and develop.

Courtesy the artist

Siân Davey

My first series [published in 2015] was about my youngest daughter, Alice, who was born with Down’s syndrome. It was ignited by feelings of anger at how I felt others perceived her. I felt a need to articulate and disseminate these feelings. In that sense, the concept preempted the work.

The series I am currently working on, about my youngest son, Joseph, was inspired by an August Sander picture I saw in a gallery in Paris. Seeing the Sander print felt like a transmission—in that moment I knew exactly what I needed to do. I have always worked in medium format (6-by-7) but decided, like Sander, to work in large format (8-by-10). Working this way strips everything down. All I am left with is myself, Joseph, and our shared histories revealing themselves in that single moment.

Courtesy the artist

Paul Graham

They go hand in glove. If you are a photographer who works with life, then you have to put yourself into the territory where that imagery and your thoughts might coalesce, because you need the vital lesson that first key image provides. Not the first image, but the first key image, the one that unlocks the door. The one you stumble over. It might surprise you by coming in from left field, taking things in a completely different direction, but that’s the beauty of working with the world, with the moments that time hurls your way. It’s a collaborative dance between the artist and life itself, so embrace the partnership. Often the world’s complexity is far more interesting than your concepts. If you can have the humility to admit that, you’ll do well.

Courtesy the artist

Gregory Halpern

My answer to this is a little messy, but working through the messiness of that process is part of the joy of fumbling my way toward clarity. It may begin with an idea, but sometimes it’s simply a hunch, or a feeling. I don’t clearly understand the evolution of the process until the work is done, and I like to take my time working on projects—A [2011] and ZZYZX [2016] each represented about five years of work, respectively. Finding out where the work will go is what keeps them going.

Once I begin to understand what will hold the work together, even if it’s just a loose binding structure at first, then I am able to narrow my field of vision, or “material,” to whatever is within the parameters of the “project.” Once I have loosely defined parameters, I am free to be as obsessive as possible within that framework. I want parameters narrow enough to make the work compelling and cohesive, but broad enough to allow myself, and my viewer, the pleasure of being able to find their own way through the work.

Courtesy the artist

Todd Hido

I always find the concepts in my work through making pictures and sorting them out, which clarifies my ideas. Most often I am using my intuition up front. The process of analyzing comes later.

Courtesy the artist

Rinko Kawauchi

Most of the time the photographs tend to be a prelude to the concept. With my earlier works Utatane and Hanabi [both 2001], for example, I carefully selected photographs to use from the pool I had accumulated after a number of years of shooting—all the while thinking about how to structure the pages of a book. To bring each to completion, at the end I went out and photographed additional shots to create the imagery I wanted to depict. For Halo [2017], a more recent work, I felt that I could achieve the desired aesthetic by amalgamating photographs I had taken for different projects—culminating in compiling the series into book form.

© Catherine Opie, Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles, and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, and Seoul

Catherine Opie

Normally the idea of the project comes first. When I begin to make a body of work, surprises or different situations often happen that allow me to think within the original idea but still experiment. So I like to start with a concept, but I also like the freedom of how it can transpire during the making of the work.

Courtesy the artist

Kristine Potter

If we want to talk about long-term projects, I typically begin with a conceptual architecture that loosely defines where I’m going and whom I’m looking to find. When I first began work on Manifest [2018], for example, I thought it would be comprised entirely of portraits. But you’ll notice that the body of work is full of landscape pictures: those evolved because the area, Colorado’s Western Slope, was so sparsely populated that I would sometimes go a few days without making a portrait. There I was, in this incredible landscape that had all kinds of photographic history, holding a 4-by-5 camera. It came so naturally—and I can’t imagine this work existing without the landscapes—but that wasn’t the original plan. For me, it is increasingly important to avoid treating my initial concepts as a formula or something to illustrate. These ideas are necessarily loose and the magic usually happens at the margins.

Courtesy the artist

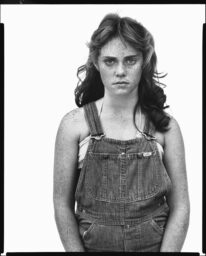

Richard Renaldi

For much of my career I have focused on specific projects. I think of an idea and execute it. Either the project develops sufficiently or eventually I drop it. I have nearly as many unfinished projects as completed ones. Sometimes, one project gives rise to another. For example, a portrait series I worked on for a number of years, photographing at Greyhound bus stations across the country, led me to attempt group portraits of strangers sitting together on public benches. Those images relayed themselves into a new idea, to shoot pictures of two or more strangers posing intimately with the stipulation that they must physically touch one another. This became the genesis for Touching Strangers [2014].

Courtesy the artist

Alec Soth

I usually start with a vague idea. But after the first exposure, this idea invariably is transformed. I’m reminded over and over again of William Carlos Williams’s “no ideas but in things.” By the time I’m done shooting, the original idea is barely recognizable.

Responses have been edited for space. To read the full interviews, order your copy of PhotoWork here.