2009 Portfolio Prize Runner Up: Jason Hanasik

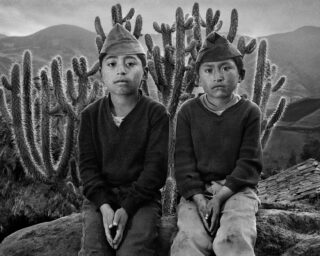

Steven in a bed of flowers, 2008

Despite commonly held assumptions, complex visual treatments of straight male masculinity are hard to come by. One could even argue that artists avoid the subject, perhaps for fear of veering uncontrollably into the realm of homoeroticism, a trap of sorts that presents itself at both the most and least overt ends of the masculine continuum.

In light of this trend, Jason Hanasik’s He Opened Up Somewhere Along the Eastern Shore is quite remarkable. Invoking the Soldier—commonly a tired, shop-worn masculine trope—Hanasik upends expectations, creating a beguiling portrayal of a gender (and military) in limbo, where individual men struggle to navigate the cultural expectations put upon them. Try as they might to contain it, emotion and vulnerability permeate the lives of Hanasik’s soldiers, Steven and Patrick, as they vacillate between the hyper-masculine world of military service and the more delicate reality of their home lives. Steven’s self-portraits, taken on duty in Iraq, show him in various states of composure, sometimes confident and collected, sometimes weary or mournful. Patrick’s expressions are more cautious, perhaps reflecting a self-consciousness about how the camera could cast him. Even so, Patrick’s surroundings betray his sensitivities—whether basking in a beam of sunlight or standing by his front door, complete with a “welcome” sign that bears an uncanny resemblance to him, Patrick’s softer side emerges tacitly from his shell.

The portfolio is also striking in that it occupies an indistinct sexual space very comfortably. Hanasik, who is openly gay, won his subjects’ trust to such an extent that, in portraying them as the multifaceted people that they are, he was allowed to photograph them in traditionally homoerotic poses—Patrick in bed, Steven in a meadow. It is a testament to Hanasik’s skill both as an artist and curator (since he did not take all of these photos himself) that these images do not tip the project into an overly sexualized realm. Rather, they serve to question not so much Patrick or Steven’s personal sexuality, but the relevance of the impulse to determine sexual preference in dry, finite terms, when so often reality is more complicated. Hanasik portrays his subjects, and by extension, men at large, as enigmatic conflations of seemingly opposing qualities: they are guarded, yet open; hardened, yet sensitive. His work questions our proclivities to pigeonhole and underestimate, encouraging us to find comfort in our ambiguities and emotion where we least expect it.

All photographs from the series He Opened Up Somewhere Along the Eastern Shore. Courtesy the artist.