Can Photographs Provide Information When Truth Is Disrupted?

The 2020 Aperture Summer Open, Information, presents new work by fourteen photographers and lens-based artists who examine globalization, technology, and politics, and the dynamic changes to personal and social identity charted by mass media today. They consider declassified military archives and CIA conspiracy theories, stage encounters with race and memory, present evidence of incarceration and violence, and visualize the physical spaces where digital information is concealed from the public eye. While some artists interrogate the construction of images themselves, others rely on the photograph’s power to cross between dream and dystopia, fact and fable. Together, they broadcast new ways of viewing our present—and our future.

Javier Alvarez is a documentary photographer who examines inequality and social justice. His project PRÉDIO (Portuguese for “building”) explores the Marconi building, a repurposed office tower in São Paulo. In the 1990s, workers and social activists broke into the building and began squatting there. In 2013, Alvarez started visiting the Marconi building regularly, living there off and on a few times per year for up to eight weeks at a time, and began compiling a series of photographs, video footage, interviews, archival material, and collages from a personal travel journal, all of which deal with themes of home and family (or lack thereof), social responsibility, and the power of visibility. Alvarez deftly adapts his work to match the improvised style of those living in the Marconi building: he layers short, emotional accounts on top of and around images; collages hand-colored pages; and tapes portraits into his small notebook. Toggling between images of entire buildings and close-cropped portraits, Alvarez portrays the Marconi building as a metaphor for the issues facing urban life and survival in contemporary Brazil. —Luke Bolster

The photographs in Gus Aronson’s series Eurydice are individual stories of engagement with obsessions and motifs found in his wanderings, yet together, they provide point and counterpoint, fact and fiction. Central to the series is an attempt to visualize the myth of Orpheus, who travels to the underworld to retrieve his wife, Eurydice, only to lose her again when, breaking the set conditions for Eurydice’s return, he turns back to see if she’s still following behind him on their way out. While the story is often interpreted as one of love and despair, Aronson prefers to center the act of looking. Photography does not have to be a record of the past but can remain in a constant present or envision a potential future. In Eurydice, pictures of hands flipping through a photo album, or of an artist painting a facsimile, break down the temporal walls that confine old theories of photographic fact. “Don’t look back,” these pictures seem to say. “Keep moving, and see what you will find.” —Eli Cohen

As a Haitian-born artist now based in New York, Widline Cadet’s identity is deeply rooted in duality. At the center of this duality is the self, the subject Cadet investigates most thoroughly in her project Seremoni Disparisyon (Ritual [Dis]appearances). Across her images, she considers how race, memory, migration, and specifically Haitian cultural identity function in the United States. With other women often serving as her doubles in “self-portraits”—flashes or scarves obscuring their faces—Cadet thinks of photography as “a means of disappearing into visibility,” a sentiment that arises from the fact that for immigrants, especially those who are undocumented, recognition or surveillance can be dangerous. For Cadet, a photograph can provide a form of camouflage, actively disrupting a viewer’s expectations and offering to her subjects—and herself—a sense of poetic visual presence. —Luke Bolster

Emma Cantor’s series The Production of Certainty investigates the material presence of information in the digital age—the flow and protection of information through data servers and fiber-optic cables, and the destruction of information in high-security facilities. “The physical presence of information is both hidden and also, with each passing year, shrinking,” she says. Storage units, the transfer of confidential documents, and a private investigator’s inventory each represent tangible forms of information otherwise invisible and transferred online, yet a blasted hard drive or an Infoshred worker vacuuming shreds of paper dramatize destruction. The facilities where Cantor photographed, what she calls “physical spaces concerned with the material reality of digital information,” are a backdrop to illustrating the spectacular erasure of information in a time when most records of our personal and professional lives would seem, paradoxically, to have a permanent digital footprint. —Zora Gandhi

Yu-Chen Chiu’s work focuses on notions of migration and belonging in the United States, her “second home,” as she puts it. In her project America Seen, Chiu brings an outsider’s perspective to the country’s tumultuous social and political moment. The project, she says, is “a visual poem about the social landscape of the United States during the Trump administration.” Rather than exacerbate the deeply personal and often volatile themes of race and patriotism, Chiu crafts subdued and contemplative images. Through the use of black and white, and somber subjects framed by buildings or train windows, Chiu creates images that border on memories or dreams, vaguely familiar, but just out of reach of comfortable nostalgia. Her work attempts to access the varied nature of America, “from the happy dreamers to the lonely wanderers.”—Luke Bolster

Theory and practice intersect in Ash Garwood’s Common Fault, a series of grandiose gelatin-silver prints, where an uncanny valley of landscape photography meets digitally constructed images. The process begins in Cinema 4D, a modeling software in which Garwood pieces together photographs with generated textures to render a negative that is then developed and printed in the darkroom. Garwood does not hide the construction, deciding instead to showcase the process as a focal point in understanding the work; when the final image hangs on the wall, it performs as both photograph and digital art. Garwood’s landscapes bring together seemingly disparate ideas about queer theory, environmental studies, and quantum physics into depictions both familiar and unrecognizable: a mountain range could look like an ocean, a rocky field like the surface of the moon. In presenting digitally created works that “pass” as landscape photographs—in a confluence of the word’s meanings—Garwood reclaims the power implicit in producing landscape imagery, a field often dominated by white, male, heteronormative, settler-colonial ideas of power. Rather than evading ideals of authority and reality, her prints invite the viewer to the feeling of uncertainty. —Eli Cohen

Growing up in the Virginia suburbs of Washington, DC, Evan Hume spent much of his life in close proximity to the operational center of the US government. In his work, Hume transmits a version of this early familiarity to a wider audience. Through years of research and requests through the Freedom of Information Act, Hume has amassed a collection of informational photographs from agencies such as the CIA, FBI, and NSA. Viewing Distance deals with the form of photography as much as with its content. Leaning into both deliberate redactions and unintentional distortions that occur after years of archival storage and repeated photocopying, Hume’s work evaluates the supposed authenticity of an image as well as its subject matter. Presenting what he calls “historical fragments in a state of flux,” Hume shows how incomplete, indeterminate, and fluid images can be, despite capturing a fixed moment in time. The line between past and present is often blurred—modern iPhones sitting on top of stacks of old, Polaroid-type photographs; or futuristic jets flying across black-and-white, grainy landscapes. These distortions probe the source of the image, and the time between its capture and the present. —Luke Bolster

Balancing natural and unnatural elements in the frame, Seunggu Kim highlights the societal ironies embedded in contemporary Korean life. In the large-scale images of his project Better Days, Kim shows people enjoying leisure activities in crowded scenes, the cityscape of Seoul looming in the background—people work so many hours and have so few vacation days that they’re unable to travel very far. “People are sincere, optimistic, and dynamic,” Kim says. Crowds enjoy their limited time off amongst one another, camp alongside each other, assist each other in taking group photos, maintain a watchful eye over children in a swimming pool. This enduring sense of community—possibly a fantasy, definitely a dream in the era of pandemic—reminds us: is there anything more important than living happily together? —Allie Monck

Who controls the conversation around Black men in the media? This question animates the artist and photojournalist Joshua Rashaad McFadden’s project Evidence, which revolves around the seven years he lived in Atlanta. His time there exposed him to the numerous and disproportionate ways violence is enacted on Black people in the US. Transcending statistics to focus on individual lives and experiences, McFadden confronts the conventional, too-often negative representations of Black men in America by including, alongside his portraits, written testimony, historical newspapers, and conversations with and texts by playwrights, actors, and historians. Evidence is a project of disruption, what McFadden calls “an archive to reframe societal views of Black masculinity and gender identity.” As an homage to Frederick Douglass’s The North Star antislavery newspaper, McFadden’s own broadsheet, Evidence, acts as both a way of transmitting information and as a pure artistic pursuit that extends beyond the museum walls. McFadden’s work is ultimately optimistic, but nuanced, as he pushes for photographs and words to recognize Black men’s lives as a “collective story you can’t ignore.” —Luke Bolster

In October 2019, protests erupted across Bolivia after a national election resulted in claims of fraud committed by then president Evo Morales, who returned with a counterclaim calling the protests a coup. Over the next month, Morales would resign, the conservative senator Jeanine Áñez would step in as an interim leader, and a new election date would be set for 2020. In the meantime, protests turned violent. Photographs of protesters and rioters circulated worldwide as people watched the unfolding events in Bolivia. Daniel Mebarek, whose family is Bolivian and Algerian, and whose uncle and grandfather were involved in Bolivian revolutionary politics—his grandfather was killed in 1971, during Hugo Banzer Suárez’s dictatorship—converges two distinct sets of photographs in his series La Lucha Continua (The Struggle Continues). One comes from archival material—pamphlets, family photographs, and identity photographs that Mebarek collected in recent years from his family members—which he has remade as cyanotypes. He pairs these with photographs he made in January in La Paz. A direct challenge to a historically linear vision of protest and progress in Latin America, La Lucha Continua seeks to define a space between archive and news, past and present, what Mebarek refers to as “the loopholes in official memory.” —Eli Cohen

Kean O’Brien’s interdisciplinary projects focus on masculinity, queer strategies for survival, and the construction of identity. His project Mapping a Genocide attempts to “develop a theoretical bridge between environmental and social justice” by documenting sites where transgender individuals were murdered, and noting how unexceptional many of these spaces appear. By using Google Maps to create images of intersections and neighborhoods, O’Brien co-opts a technology of surveillance in an effort to create a queer cartography of life and death. Mapping a Genocide asks viewers to imagine a world that is free of radicalized and gendered violence. Instead of prints, O’Brien presents the work as a slideshow, with images flickering in and out of presence, an evanescent quality that serves as a reminder, he says, that “trans people are verbs rather than nouns and are ever evolving and shifting. And so is the meaning of these landscape maps that we occupy and place ourselves within.” —Allie Monck

Florence Omotoyo’s photography explores the impact of social surroundings on narratives of identity in the UK, often highlighting communal spaces and transit systems. For her series Everywhere + Nowhere, she stages photographs of seemingly mundane acts, such as commuting, gathering with one’s friends, and moments of solitude. “As much as we may present and embody a group or collective,” she says, “on a deeper level, we are ruled by a set of histories, perspectives, and tastes that can only be explored by first looking at the solo individual.” This framing of community is threaded throughout Everywhere + Nowhere, emphasizing the multitudes that exist in everyday spaces. Whether depictions of waiting for a train, joining a group of friends, or taking selfies in the bathroom, Omotoyo’s photographs consider “alternative ways to be away from the structures and systems that have continuously perpetuated the same story.” —Allie Monck

Rowan Renee is a genderqueer artist who examines the complex and restrictive relationship that law enforcement has with queer identity, addressing intergenerational trauma, gender-based violence, and the impact of the criminal justice system. Their project No Spirit For Me is a deeply personal examination of the evidence compiled by the Florida State Attorney surrounding Renee’s father’s criminal prosecution in 2008. Renee recreates the official photographs as photolithographs, adding little alteration to the cold, factual images. The transformation from digital to print mimics the transformation that these once mundane items underwent upon their father’s prosecution—VHS tapes, cameras, and computers emerge as pastel-hued ready-mades, objects of inquiry and mystery. No Spirit For Me invokes the violence inherent in the criminal justice system, pushing the limits of photography’s “burden of proof” by showing how it uses, or misuses, imagery to enforce official narratives. —Luke Bolster

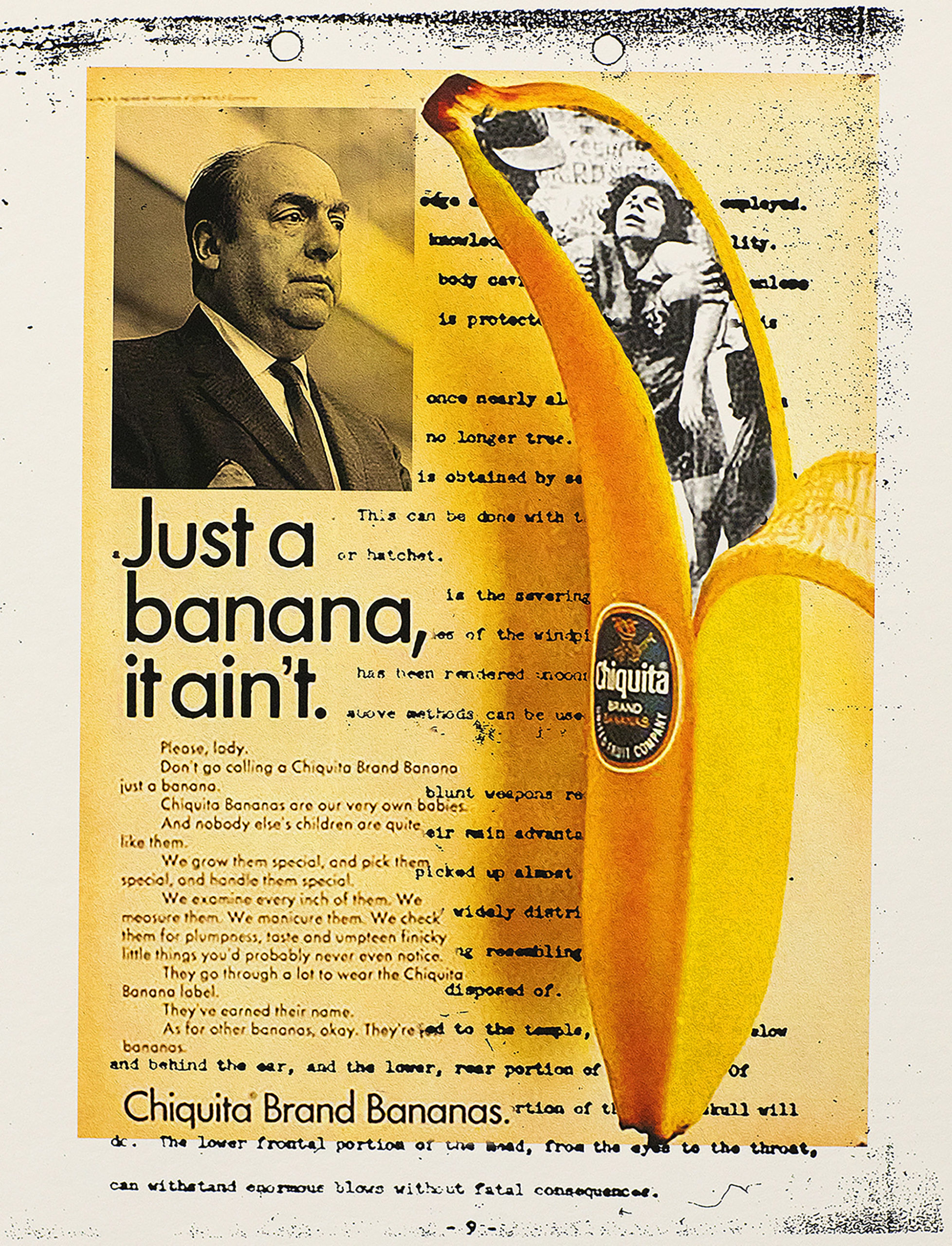

A Study of Assassination, declassified through the Freedom of Information Act in 1997, was a manual developed prior to the US-backed 1954 coup in Guatemala and details the CIA’s methods and standards for extrajudicial killings. The United Fruit Company, which had ties to the destabilization of multiple Latin American governments, was entangled in the violence and has settled class action lawsuits regarding its funding of paramilitary groups in Colombia as recently as 2018 under its current conglomerate, Chiquita Brands International. Alongside his photographic interpretations of A Study of Assassination, George Selley collages images of Chiquita bananas and military photographs together with pages from the manual—specifically, instructions on how to divert attention and operate covertly. He uses quotes from the manual as captions, the tense language often removing the agent from the act of killing. Selley’s reconstruction of the manual underscores the disturbing realities of American involvement in Latin America and the strategic alliance between capitalist enterprise and corrupt governance that continues to this day. —Eli Cohen

The 2020 Aperture Summer Open, Information, is curated by Brendan Embser, managing editor of Aperture magazine, with Farah Al Qasimi, artist; Amanda Hajjar, director of exhibitions at Fotografiska; Kristen Lubben, executive director of the Magnum Foundation; and Paul Moakley, editor at large for special projects at TIME. The exhibition is on view at Fotografiska New York through October 25, 2020.