2020 PhotoBook Awards Shortlist: First PhotoBook

The First PhotoBook category celebrates the creativity and commitment to bookmaking by photographers publishing for the first time, highlighting new work by June Canedo de Souza, Ronghui Chen, Buck Ellison, and more.

Ronghiu Chen from Freezing Land (2020)

Paris Photo and Aperture Foundation, in partnership with DELPIRE & CO, are pleased to present the shortlisted books for the 2020 Paris Photo–Aperture Foundation First PhotoBook Award.

The First PhotoBook category highlights the creativity and commitment to bookmaking by photographers publishing for the first time. This year’s shortlist includes a wide range of publications—from June Canedo de Souza’s self-published title about family separation, and Maryna Brodovska’s social-media inspired paean to long-distance friendship, to this year’s winner, Buck Ellison’s thoughtfully crafted book about the visual language of privilege.

This year’s shortlist was selected by a jury comprised of Joshua Chuang (New York Public Library), Lesley A. Martin (Aperture Foundation), Sarah Hermanson Meister (MoMA), Susan Meiselas (photographer, Magnum Foundation), and Oluremi C. Onabanjo (independent curator and historian).

Courtesy the artist

Predicting the Past—Zohar Studios: The Lost Years is a rare example of where more actually is more. “Absurd—just completely over the top,” says Sarah Meister. “This book has plenty of signals why it is not what it purports to be from the start.” Its oversized scale and heft resembles a compendium publication for a nineteenth-century studio photographer’s lifetime achievement, precisely what the artist Stephen Berkman aims to evoke with his antiquated glass-plate work and the fictive Zohar Studios—similar to artist Joan Fontcuberta’s elaborate trickster approach. Meister notes, “The minute you realize that what you’re looking at is constructed and new, you find incredible humor.” With images like a man selling a trunkful of merkin samples, Berkman’s wit seems inexhaustible. Meister concludes, “If the immense ambition and scale of this work were anything less, it would not achieve the same impact.”

Courtesy the artist

Pleasant Street by Judith Black (STANLEY/BARKER, Shrewsbury, United Kingdom, 2020)

In 1979, Judith Black moved with her children to Cambridge, Massachusetts, where she knew no one. She began to turn her lens toward her children and the dilapidated apartment they shared. Pleasant Street is “a gentle chronicle of a family over two decades,” says Susan Meiselas, one that takes the viewer through Black’s life as a mother watching her children grow up. Organized chronologically, we watch through Black’s eyes as her children grow older, become taller, change hairstyles, learn to express themselves, and eventually, become adults. In some cases, Black turns the camera on herself, documenting her own changes alongside her children’s. “The balance of the family members not only looking at themselves, but at each other, seems quite perfect,” Meiselas concludes. The book is full of photographic gems underscored by the rich black-and-white reproductions of each image, presented with a generous border and without titles; handwritten captions appear at the back of the book.

Courtesy the artist

My Dear Vira by Maryna Brodovska (Self-published, Kyiv, Ukraine, 2020)

Maryna Brodovska’s My Dear Vira acts as a letter addressed to her childhood friend, who emigrated to the United States from Ukraine more than eight years earlier. The book feels like a Tumblr account in book form: candid snapshots from the friends’ lives together and apart are mixed together with screen captures from their social-media correspondence—sometimes with direct intervention from Brodovska in the form of collage or vividly colored scribbles, personal notes, and even a page of stickers. The book tells the story of their friendship and life-long bond in a playful, nostalgic, deeply intimate way. The story operates on multiple levels, considering not only their shifting relationship over time, but also the changing geopolitical relationship between their two countries. “The conflation of popular-culture reference points, embrace of bright colors, and dizzying design formats across spreads give a sense of confusion at moments—but in the best way,” Oluremi C. Onabanjo comments. “It’s a really loving, enjoyably strange rendition.”

Courtesy the artist

Mara Kuya by June Canedo de Souza (Small Editions, Self-Published, Brooklyn, 2020)

June Canedo de Souza’s Mara Kuya tells the story of a family separated by citizenship status. Taken over the course of seven years between Brazil and South Carolina, Canedo’s photographs present a striking, yet tender look into her family’s life and experiences, while also considering the often overlooked emotional and psychological toll caused by migration and separation. Encased in a bright yellow cover, Canedo’s lush and colorful photographs are interwoven with her own short written reflections. The resulting narrative and sequence unfold with a poetic impressionism, offering a deeply personal and nuanced perspective of this global experience. Onabanjo comments, “Mara Kuya considers the depths of what an intimate story can convey to us over the course of a photobook, as disclosed from the specific position of a Brazilian American woman, artist, and photographer.”

Courtesy the artist

Freezing Land by Ronghui Chen (Jiazazhi Press, Ningbo, China, 2020)

Chinese photographer Ronghui Chen documents the uncertainty and isolation of young people amid the colorful but derelict landscape of China’s northeast region in Freezing Land, which investigates the once prosperous northeast region and the burdens and hopes of its youth. Chen used a video-sharing mobile app, Kuaishou, to find people willing to tell their stories. The resulting portraits—informed by photographers such as Alec Soth, Joel Sternfeld, and Zhang Kechun—capture a tangible mixture of hesitation, loneliness, and hope. Softcover and printed on uncoated paper, the book’s overall design feels suitably spare; the accompanying text appears in both Chinese and English. “Freezing Land is a standout debut by a promising contemporary Chinese photographer,” juror Joshua Chuang states. “Chen shows a side of the modern Chinese story that eludes cliché and helps round out our understanding of the country as a whole.”

Courtesy the artist

2020 Juror’s Special Mention: LIKE by Ryan Debolski (Gnomic Book, Brooklyn, 2020)

LIKE explores the experiences and relationships of migrant workers in Oman. But rather than focusing on the defining public image of poor working conditions, photographer Ryan Debolski depicts men finding agency and connection to the landscape of the beach and companionship in each other—they are as playful as they are introspective. A running dialogue of conversations via text message weaves together details of infrastructure and landscape and highlights the men’s digital communications with one another. LIKE refuses to dehumanize or mystify the laborer, and an accompanying essay by Jason Koxvold, “Raw Material: Capital and Exploitation at the Neoliberal Frontier,” contextualizes the work in the history of representation of labor in art. “The editing of this book is superb,” Chuang acclaims, “a compelling entrée into the roster of photobooks about lives otherwise lived out anonymously.”

Courtesy the artists and Poursuite

Los Angeles Standards by Caroline and Cyril Desroche (Poursuite, Arles, France, 2020)

Los Angeles Standards is a photographic portrait of Los Angeles, an iconic city in continuous flux and an experimental laboratory for twentieth-century architecture. Boasting 1,300 photographs taken between 2008 and 2012 by French architects Caroline and Cyril Desroche, the book is divided into fifteen typologies that compare and contrast defining archetypes of the city’s sprawling urban landscape—minimalls, billboards, freeways, parking lots, microarchitectures, and stilt houses, among others. This chunky brick of a book presents the work via a rigorous design that Chuang calls “a pleasure to flip through again and again.” The Desroches nod to the likes of Ed Ruscha, Learning from Las Vegas (1972), and Bernd and Hilla Becher. Los Angeles Standards both records and deconstructs the fragmented urbanism of Los Angeles—reflecting on its history and present identity, which, as Chuang states, “in its totality and density, gets to the heart of what makes Los Angeles distinct.”

Courtesy the artist and Loose Joints

Buck Ellison’s Living Trust investigates the visual language of privilege. Organized into chapters named by subject—such as “Daughters,” “Still Lifes,” and “Performance Fleece”—the book also includes two text contributions by Lucy Ives and Brooke Harrington. Photographs range from overtly staged Christmas cards and portraits, to still lifes of food and flowers and upper-middle-class activities, such as lacrosse, rowing, and golf. Taken together, these series offer a sustained, almost anthropological examination of the ways whiteness and privilege are both recapitulated and broadcast. “Living Trust emerged in our conversations as something that focuses really well on what many take for granted,” Onabanjo comments. “It is important to consider and make visible the silent violence and security of whiteness as it is continually maintained. This book does that precisely.”

Courtesy Edition Patrick Frey

MOM by Charlie Engman (Edition Patrick Frey, Zurich, 2020)

MOM is an intense collaboration between photographer Charlie Engman and his mother, Kathleen McCain Engman, who has been posing for her son since 2009. Containing a decade’s worth of portraits—and rich with fashion, art, and photo-history references—MOM possesses what Chuang calls “a strange magnetism and delirious complexity.” Through an exhaustive array of personas and performative situations, Engman and his mother experiment with discomfort, artifice, vulnerability, and familiarity. “Engman’s project has shades of the conceptual masquerade of Cindy Sherman, the outrageousness of Juergen Teller, and the critique of Boris Mikhailov,” Chuang says. MOM tests boundaries in a rigorous display of creative control, collaboration, and deep trust.

Courtesy the artist

Courtesy the artist

Recetario para la memoria by Zahara Gómez Lucini (Self-published, Mexico City, 2020)

Can cooking be a form of activism? And can a recipe-driven cookbook also be considered a compelling photobook? Recetario para la memoria (Memory recipe book) stronglymakes the case that the answer is yes. Author Zahara Gómez Lucini serves as the project coordinator and photographer, working with Las Rastreadoras del Fuerte, a group of Sinaloense women dedicated to finding their missing loved ones. The book presents a series of recipes for the favorite dishes of various disappeared family members, interspersed with photos of the dishes and of the women midpreparation, and with recollections of those who are missing. “Recetario para la memoria proposes an unexpected interpretation of the photobook, in the process, tapping into questions of memory, state violence, and familial connectedness,” Onabanjo states. “Ultimately, it offers a portal for remembrance while engaging with an important element that people share with their loved ones who are no longer there—the food that brought them together.”

Courtesy the artist

Road through Midnight: A Civil Rights Memorial, by Jessica Ingram, is a deeply researched body of work that brings together photographs, oral histories, newspapers, FBI files, and other ephemera to tell the stories of individuals who were victims of racial violence in the American South. Released at a time of ongoing civil unrest, Ingram’s book is a stark reminder of America’s long racist history and an indication that what is happening today is not so different from the past. The photographs depict seemingly ordinary spaces—neighborhood sidewalks, motels, unmarked dirt roads—but, in the manner of Joel Sterneld’s On This Site: Landscape in Memoriam (Chronicle Books, 1996), depict places where heinous crimes against Black Americans took place. Ingram “looks to uncover and reveal the history of violence while searching to relearn histories that are buried and obscured,” notes Meiselas. No plaques or monuments mark these spaces; instead, Ingram “brings greater visibility to what is left for us to revisit and learn.”

Courtesy the artist

Regarding Paul R. Williams: A Photographer’s View is a visual duet between architect Paul R. Williams and Los Angeles–based photographer Janna Ireland. Popularly known as “Hollywood’s architect,” Williams designed buildings in his native Los Angeles with versatile range. His achievements broke racial boundaries: in 1923, as the first Black member of the American Institute of Architects; and in 2017, posthumously, as the first Black recipient of the prestigious AIA Gold Medal. Meister observes, “Ireland works in black and white, which softens but doesn’t erase the passage of time.” She is also sensitive to this past, approaching the creation of a lyrical photographic record of Williams’s achievements as both a personal and restorative tribute. “This book is a real discovery and delight,” says Meister, reflecting on the omission of Black artists’ and architects’ work in institutional collections, “a loving photographic tribute to the legacy of this important architect and an entry point into both Ireland’s and Williams’s work.”

Courtesy the artist

’O Post Mio by Francesca Leonardi (Postcart Edizioni, Rome, 2020)

’O Post Mio follows the life of Claudia and her two daughters, who live in Saraceno Park, an illegal building complex in the village of Coppola, near Naples, Italy. For eight years, Francesca Leonardi has photographed Claudia, capturing intimate family moments, struggles, and growth among a crumbling landscape. Leonardi beautifully captures Claudia’s struggle to be the mother she never had. The work is a lyrical, if unflinching journey into motherhood. “The photographer’s eye remains focused on the small moments—everydayness and the banal. Moments that are harsh but telling,” Meiselas notes. The book is intimate in scale, with a deep red cover and bound-in pink pages that include text by Claudia about her estranged mother. “The book intrigued me the moment I opened it and discovered two different kinds of readings—phrases and fragments, and a strong visual narrative,” states Meiselas.

Courtesy the artist/Magnum Photos

La casa que sangra by Yael Martínez (KWY Ediciones, Lima, Peru, 2019)

Based in Guerrero, Mexico, Yael Martínez has spent a considerable amount of his career thinking about and documenting the impact narco trafficking has had on his community and region. This project, however, brings home the violence and its effects in a personal and harrowing way, focusing on the murder of three of his brothers-in-law and the lives of their extended families as they struggle with these losses. “The work is threaded together with a profound sense of melancholia and loss,” notes Martin. The story is told bilingually from Martínez’s perspective, who speaks of nightmares and nausea in the aftermath of each murder, one of which was initially passed off as a suicide in jail. “These bite-size narratives hit hard,” Martin observes. “The book is rigorously constructed: from the carefully controlled and muted palette, to the interwoven text elements connecting personal traumas, to larger stories of endemic violence, corruption, and the increasing dominance of organized crime in the photographer’s homeland.”

Courtesy J&L Books

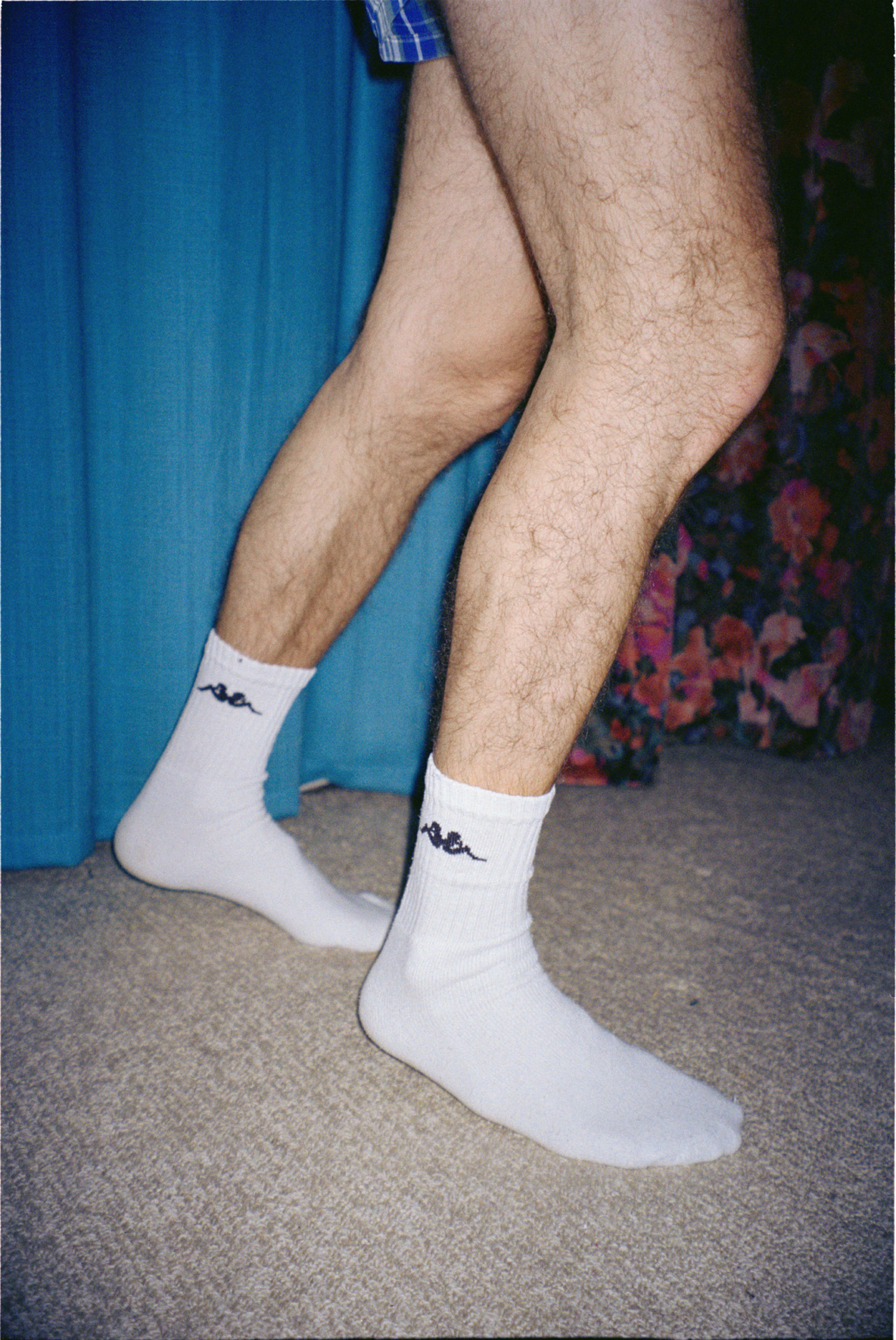

My Father’s Legs by Sara Perovic (J&L Books, New York, 2020)

In My Father’s Legs, Sara Perovic presents what Martin calls “a charmingly obsessive photographic meditation on the arbitrariness of what makes us fall in love.” For Perovic’s mother, it was her spouse’s tennis-sturdy legs, photographs of which appear intermittently throughout the book, reproduced in exaggerated, blue halftone on pink paper. Tennis may have made her father’s legs beautiful, but—as a singular line of text explains—as a child, the artist also felt that the sport took her father’s attention away from her. The rest of the book comprises photos the artist took of her boyfriend’s legs, crouched in a similar, ready-to-serve pose. “It’s a lighthearted riff on the typological, fetishistic way that photographs can be used to both commemorate and exorcise a personal fixation,” Martin suggests, “a mesmerizing little book that showcases how a simple conceptual project can be effectively framed via a rigorous design treatment.”

Courtesy the artist

East of Nowhere by Fabio Ponzio (Thames & Hudson, London, 2020)

East of Nowhere is a collection of photographs made by Fabio Ponzio over two decades throughout Central and Eastern Europe, before and after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Although Ponzio’s photographs depict countries on the brink of radical transformation and individuals struggling to survive, they are also filled with a vibrant, timeless energy. Meiselas observes that in these photographs, “elegance frames a respect for seeing time pass—the stillness, the waiting—hoping to be filled with the promise of an unknown future.” The book is an expansive documentation of turbulent times, yet sprinkled throughout are moments of joy and pleasure—a couple celebrating on their wedding day, a group of men enjoying a drink together. With sumptuous reproductions that showcase the richness of his photographs, Ponzio’s book leaves a lasting impression.

Courtesy the artist

Where the Birds Never Sing is a riveting story told in fits and starts, gathering together a series of images, documents, and textual commentary to address the 1979 massacre of Bengali refugees on Marichjhapi Island in Sundarban, West Bengal. Soumya Sankar Bose has worked with survivors of this traumatic event to recall and, at times, reenact memories of their survival for his camera. Their stories and the resulting images are buttressed by a number of small-scale facsimiles of various governmental reports tipped into the pages of the book—rare fragments of documentation that have survived an effort to destroy official evidence of the incident, one of the many violent repercussions that continue to follow, decades later, in the wake of Indian independence and partition. The results, per Martin, form a “strong example of book making in the subjective documentary mode.”

Courtesy the artist

HOAX by Agnieszka Sejud (Self-published, Wrocław, Poland, 2020)

HOAX, a crowdfunded book by Polish photographer Agnieszka Sejud, is an extraordinarily vivid barrage of wildly patterned, digitally tweaked street scenes and details. What’s “real” and what’s been tampered with is called into question on every page. The images are printed full-bleed on thick, hyperglossy paper. The spreads come nestled together in a clear vinyl envelope, and the unbound pages, like the images themselves, feel tantalizingly on the verge of falling into creative chaos. The sequence weaves together photographs of religious and national iconography with acid-color scenes of everyday consumerism—a mash-up of the sacred and the kitsch that is simultaneously seductive and seditious. “While this is more a thrilling short story than a novel,” comments Martin, “it effectively delivers a sly and visceral critique of the manipulation of contemporary values in Poland (and elsewhere) today.”

Courtesy the artist

Flower Smuggler by Diana Tamane (Art Paper Editions, Ghent, Belgium, 2019)

In Flower Smuggler, Diana Tamane edits together multiple suites of deceptively ordinary and eclectic photographs to describe her mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother. “This book hits all the right notes about the ways in which life and photography can intersect,” praises Meister. The artist collects colloquial images from her family and works with her relatives to jointly stage and create some of the images. In doing so, Tamane suggests how the meaning of photographs, their significance as artifacts of daily life and memory, can change profoundly over time. The concluding series, arguably the most poignant, is of rephotographed drugstore prints that were used by her great-grandmother to record her daily heart rate and blood pressure, with notations made on the back—and even the front—of the pictures. “This final statement in the book enriches Tamane’s endeavor while raising vital questions about why photographs matter today and to whom,” Meister notes.

Courtesy the artist

n e w f l e s h (Gnomic Book, Brooklyn, 2019)

n e w f l e s h is a curatorial exploration that recasts concepts of queerness in relation to the body. This compilation encompasses a diverse set of practices, including abstract, studio-constructed, and digitally manipulated images by artists of various backgrounds and levels of experience. Meister explains, “Parts of the work might be seen as obliquely interested in questions of queerness, while others are more direct. Combined, they represent a truly personal perspective.” n e w f l e s h draws parallels between bodily experience and photography—and their shared transformative potential to render forms of sexuality and identity free from societal constructs or physical limits. In its modest scale, the book is inviting as an object, with thoughtful binding choices that complement its vision: softcover, with an exposed and printed spine, and a reflective bronze shape on the cover that evokes a shimmering fleshy feel.

These text were originally were published in Issue #18 of The PhotoBook Review.

The 2020 Paris Photo—Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards Shortlist Exhibition will be on view at DELPIRE & CO through December 24, 2020. Read more about the 2020 PhotoBook Award Winners here.