A Biennial in Houston Explores the Politics of Visibility

The latest edition of FotoFest features artists and collectives from around the world who consider the weight of history on the present.

Phillip Pyle II, Forgotten Struggle #32, 2023

Courtesy the artist

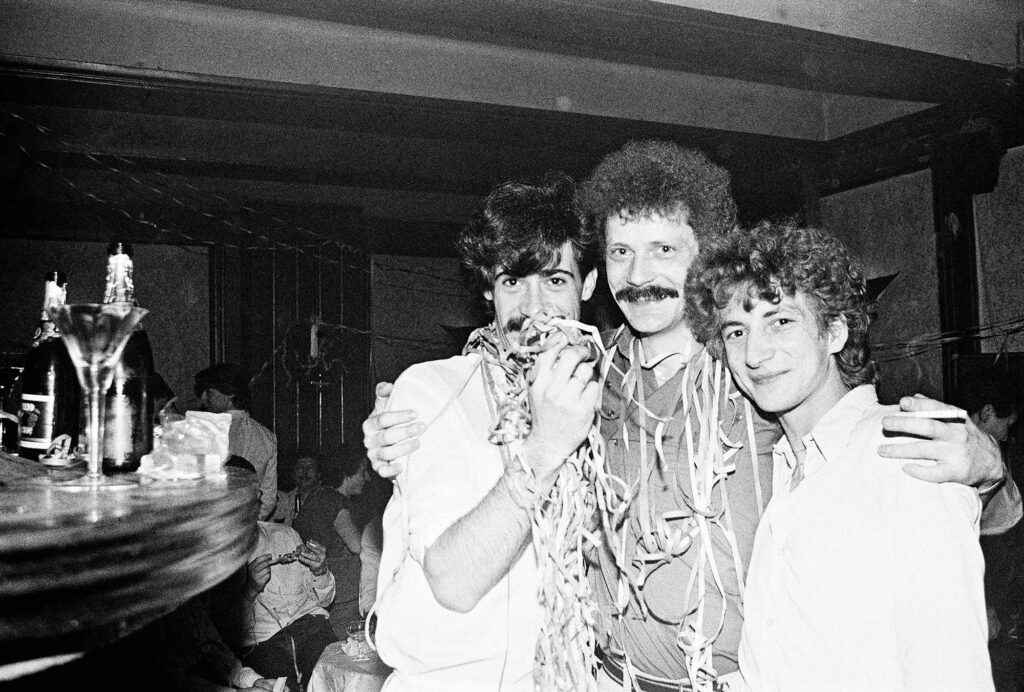

In the waning decades of Soviet rule in Czechoslovakia, Prague’s T-Club was an open secret. The clandestine gay nightclub had claimed its own gravitational force, tucked into a basement behind Wenceslas Square, where much of the drama of the 1968 Prague Spring and the subsequent “normalization” period were playing out. It was an anxious time, and the country was quickly sliding back into autocratic rule; there were widespread crackdowns on pro-democracy reformists and state eyes were everywhere. For patrons who were marginalized by the sitting regime for their sexuality and politics, T-Club was a space of possibility and freedom—however precarious—but also one where the presence of plainclothes police was routine.

The photographer Libuše Jarcovjáková came of age in this Prague. She was still a teenager when Soviet tanks rolled into the city in the late 1960s, and over the years, she charted a private geography that ultimately led her to T-Club in the early ’80s. It was here that Jarcovjáková learned to see with the intimacy and intensity that define her vibrant, monochrome images. People draped over chairs, tables, and one another in a drunken stupor; glimmers of leather, sequin, and metal, all shining against Jarcovjáková’s totalizing flash, which was both a practical necessity and form of permission. She wanted to get as close as possible—and perhaps to even try and bridge that impossible gap the camera creates. “I am trying to document the world . . . without describing it,” she writes in a diary entry. At a time when the camera invited suspicion, Jarcovjáková’s photographs freeze the club in opposition to the political reality aboveground. Her subjects stare directly into her lens, insisting on their presence.

Courtesy FotoFest

Photographs from T-Club—now the subject of a photobook and documentary—fill a quiet hallway at downtown Houston’s Sawyer Yards, the sprawling rail-yard-turned-arts-complex that has been the longtime home of the FotoFest Biennial, now in its twentieth edition. Jarcovjáková is one of many entry points into the biennial’s larger theme, Critical Geography, which explores photography’s role in constructing and critiquing our conception of place. These ideas aren’t new to the medium, but in the context of FotoFest’s wide and notably international program—featuring more than twenty artists and collectives across a central exhibition curated by executive director Steven Evans—they spark intriguing connections and contrasts.

Courtesy FotoFest

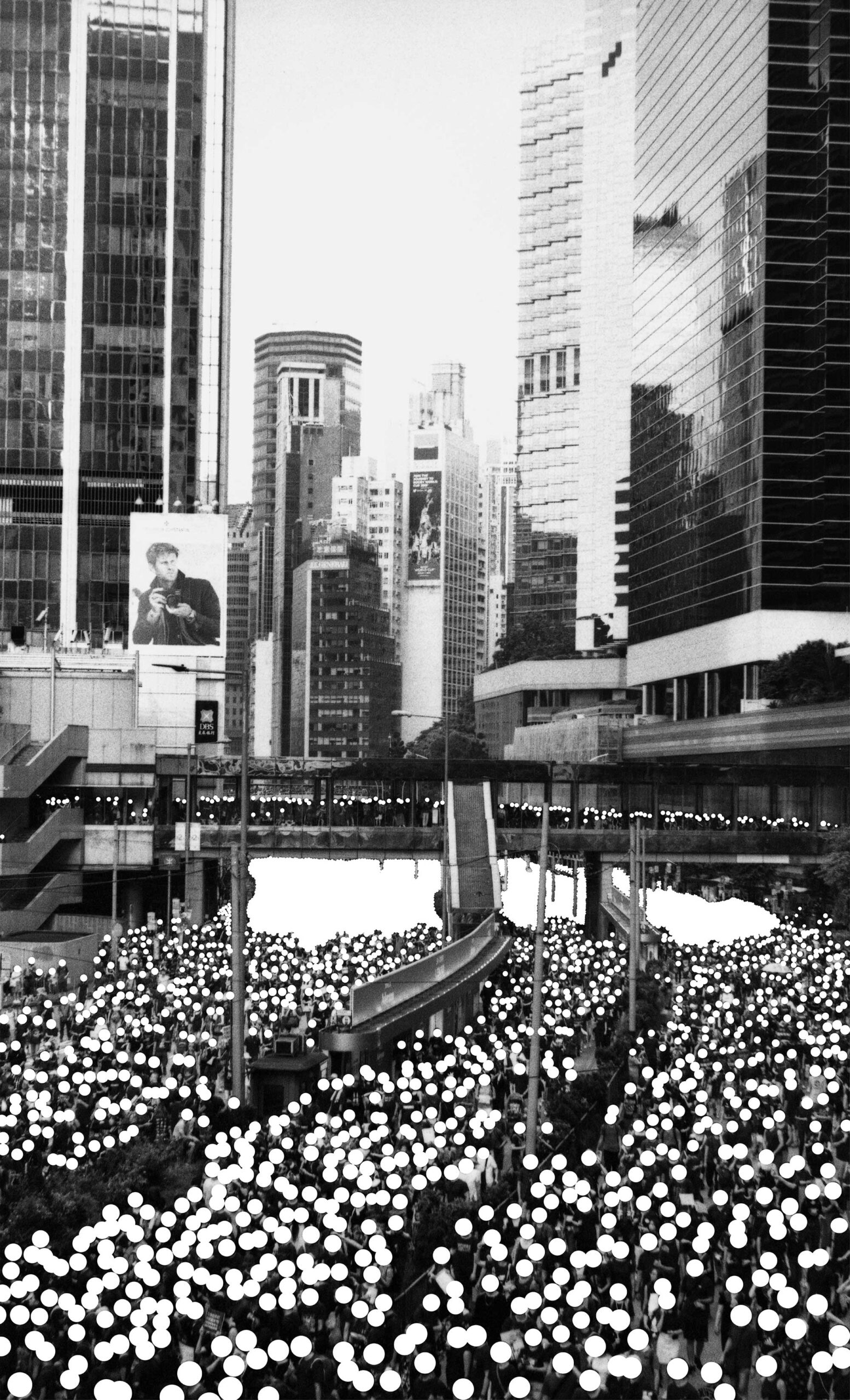

If Jarcovjáková’s work recovers a sense of spontaneity and visibility against the regimenting of public life, Siu Wai Hang’s series Clean Hong Kong Action (2019) suggests that absence can be a viable strategy for survival too. In his images of Hong Kong’s anti-extradition demonstrations, Siu obscures protestors’ faces by punching holes into his prints. The careful, repetitive omissions, and ironic series title, reframe anonymity as an active position rather than a retreat from authority, with the camera as accomplice. Houston-based artist Phillip Pyle II similarly uses strategic erasure in his series Forgotten Struggle (2011–ongoing), for which he removes all text from the picket signs of civil-rights protest photographs, provoking a reflection on the gradual dilution and removal of Black revolutionary thought and history from Texas school curricula.

Courtesy FotoFest

The politics of visibility, a motif across the biennial, gains further meaning in the work of Stephanie Syjuco. Her series Block Out the Sun (2022) asks how one might talk back to an archive, drawing on images from the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, Missouri, for which the United States government forcibly brought over a thousand people from the Philippines, then a new colony, to populate staged ethnographic scenes for American audiences. To Syjuco—who thinks deeply about how institutions and archives legitimize imperial histories—the very act of seeing these faux arrangements reinforces racist hierarchies and colonial narratives. She uses her hands to partially block the archival images and rephotographs them, evidencing the medium’s violence while denying it historical power.

Binh Danh’s daguerreotypes from All I Asking for Is My Body (2024), which sit in vitrines at the far end of an adjacent corridor, engage a related history of imperialism and enslavement. Danh, who often uses early photographic processes, impresses archival images of Japanese, Chinese, Filipino, Korean, Portuguese, and African laborers who worked across America’s plantations in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries onto silver tableware (“a symbol of sustained American colonial power and status,” as the exhibition text reads). His intervention—like Syjuco’s—wrests these images from their presumed archival facticity and questions the kinds of knowledge produced from their preservation.

Courtesy FotoFest

Courtesy FotoFest

C. Rose Smith’s series Scenes of Self: Redressing Patriarchy (2022–ongoing) likewise responds to the visual legacy of transatlantic enslavement through a subtle but sharp juxtaposition. Dressed in a white cotton shirt and code-switching between distinct gendered postures, Smith photographs themself at former American plantation sites, drawing an association between identity, fashion, place, and the performance of whiteness in the antebellum South. Presented as dye-sublimation prints on translucent white polyester, Smith’s images hang like ghostly curtains down a wide hallway, culminating in a video-performance piece. The series, a highlight of the biennial, will also be on display at Autograph ABP, London, this summer.

Courtesy the artist and Inman Gallery

In addition to its core programming, every edition of FotoFest involves several partner institutions, which mine their collections to create a dialogue with the biennial theme, spilling across Houston and its suburbs. Madrid-based artist Linarejos Moreno’s subseries On the Geography of Green, installed at Inman Gallery, is a standout. Moreno’s large-format images mimic the organizational logic of German geographer Alexander von Humboldt, who traveled and mapped American landscapes in the nineteenth century. Her photographs feature abandoned drive-in theaters in Texas, Arkansas, and Louisiana, and include a central image bracketed by an index of data, from the scientific to the subjective: numbers on geography, weather, vegetation, and, in one instance, ratings of films out during the years the theaters were active, in order of popularity. The overabundance of information reinforces Moreno’s broader point about how data’s supposed objectivity—like photography’s—both catalogs and produces specific social realities and hierarchies.

Courtesy the artist and Koslov Larsen Gallery

Nearby, at Koslov Larsen gallery, Mexican photographer Lou Peralta experiments with the limits of portraiture and sculpture for her series Disassemble (2022), introducing both contemporary local and pre-Hispanic materials and foliage into her photographic compositions. Along a similar vein, at Anya Tish Gallery, Dallas-based Vietnamese artist Han Cao hand-embroiders colorful botanical motifs onto found photographs, using her interventions to play with new ways of engaging and connecting with old images. “I am always trying to change the story of the photo,” Cao says.

Courtesy FotoFest

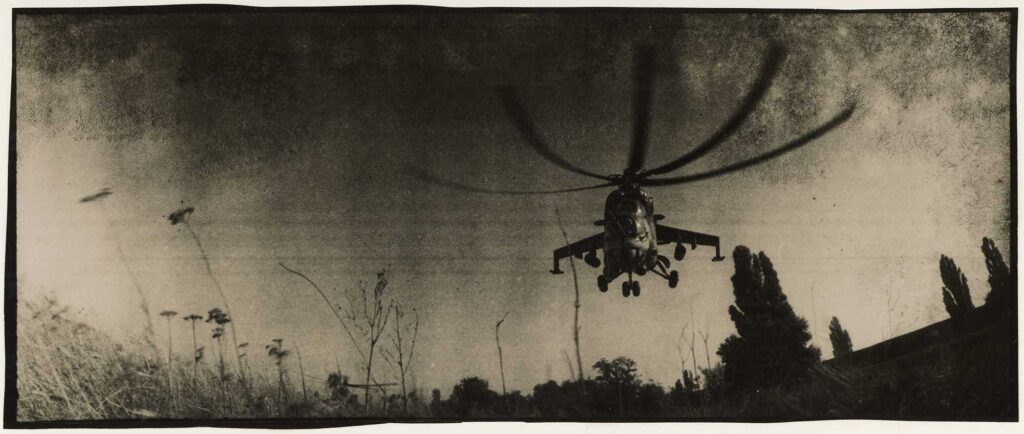

Walking the corridors of the central exhibition, one feels the weight of history—and a palpable energy among artists to reconsider its terms. Two notable works, however, bring us directly into the present day, where the relationship between the camera and the politics of place is tense and unresolved. The war-stained photographs of the series Documentation of War (2022–ongoing), by Ukrainian collective the Shilo group, chronicle the destruction of several cities, including Kharkiv, home to the group’s founding members, Sergei Lebedinsky and Vlad Krasnoshchok. Made from expired Soviet-era papers and homemade developer chemicals, the images are charged with the imprints of wartime. They constitute what artist and researcher Susan Schuppli would call a “material witness” to the conflict. The hazy, impressionistic dispatches have the effect of wet-plate prints, subverting our expectations of modern conflict imagery and the photojournalist as a detached observer. They’re reminiscent of the relationship between process and place in Blackwater, Sally Mann’s haunting, Prix Pictet–winning series from southeastern Virginia.

Courtesy FotoFest

“Images do not have an innate truth,” argues Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, writing about the Israeli government’s weaponization of images to further its occupation of Gaza. “They live in community with or against those who are involved in them.” The idea resonates throughout Critical Geography—from Jarcovjáková’s covert paradise to Siu’s public protests; from Syjuco’s belated interventions to Smith’s reclamation. Danish Scottish artist and filmmaker Shona Illingworth’s video Topologies of Air (2021) engages with this idea directly. Using precisely arranged footage, photography, and interviews across a three-channel installation, Illingworth explores our evolving relationship to the sky and how airspace has been increasingly exploited and territorialized by global corporations and governing structures. The video draws from the Airspace Tribunal, a public forum founded by Illingworth and human rights lawyer Nick Grief to advocate for a “new human right to live without physical or psychological threat from above.”

Against the larger context of increased aerial surveillance and warfare, as well as the biennial’s broader interest in placemaking as socially, politically, historically, and environmentally bound, Illingworth’s work suggests one strategy for re-narrating our historical assumptions. The broader argument proposed by Critical Geography rests on the power of such strategies, and their ability to create room for disruptions, reorientations, close readings, and—crucially—dialogue.

The 2024 FotoFest Biennial, Critical Geography, was on view at the Silver Street Studios and Winter Street Studios in Houston March 9–April 21, 2024.