A Blazing Suburban Gothic Imagines the American West on the Brink

In the 1970s, Mimi Plumb began photographing adolescent life and the bleached-out landscapes of California. Her suspenseful new book foretells the disasters of the present—and the future.

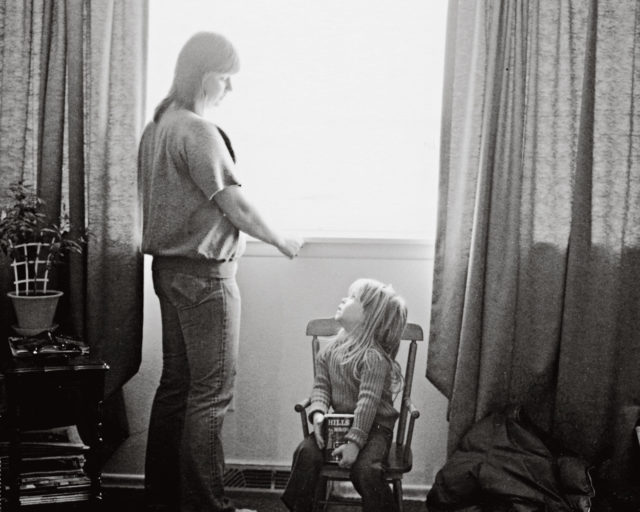

Mimi Plumb, Highway 4, 1975

The first time I moved to California was in late summer 1998, when I was young and romantic enough to refer to the place by its nickname, “the Golden State,” and to believe that this was what people there called it. (They didn’t, it turns out.) Then fall began, ushering in the ban on the use of affirmative action in admissions at all campuses of the University of California; the impeachment of President Bill Clinton; and the tule fog, which engulfed the Oakland Hills like a fuzzy grey mold. I left within the year, but not before I experienced my first earthquake and learned that the empty white skies in nineteenth-century photographs of Yosemite were casualties of overexposure—reminders of information lost more than records of light.

The second time I moved to California was in 2011, when I was old enough to recognize that its bounty and boom were largely the result of sunshine that casts noir shadows. On my departure from the East Coast, friends gave me a copy of James Ellroy’s novel The Black Dahlia (1987), which I received as a portent rather than a gift. I started to second-guess my decision to move. By the end of my first year in LA, Southern California had descended into the driest period in its history. But I stayed. Every catastrophe I’ve since witnessed here affirms what historian Bernard DeVoto wrote in his 1947 essay “The West against Itself”: “The West has always been a society living under threat of destruction by natural cataclysm and here it is, bright against the sky, inviting such cataclysm.”

This line would be a fitting epigraph to Mimi Plumb’s new photobook, The White Sky (Stanley/Barker, 2020). Its title was chosen, in part, because it simultaneously conjures an assortment of threats—aridity, extreme heat, unease, malaise—that conditioned Plumb’s early life in California. Born in Berkeley and raised about twenty miles east, in Walnut Creek, Plumb has described her adolescence in Northern California suburbia as a kind of purgatory. Intellectually stifling and insulated from the prevailing counterculture movement of the 1960s, Walnut Creek felt physically inhospitable as well, a place susceptible to drought and fire.

“I remember the summers there,” Plumb told me. “Being outside was just so hard for me as a redhead. My tolerance for sun wasn’t good. I would get sick.” She escaped Walnut Creek at age seventeen, moving across the bay to San Francisco, where she enrolled at the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI) and studied with Henry “Hank” Wessel. Work that she generated for photo classes, however, almost immediately drew her back to the Bay Area’s suburban enclaves. It was there, between 1972 and 1978, that Plumb made the photographs compiled in The White Sky.

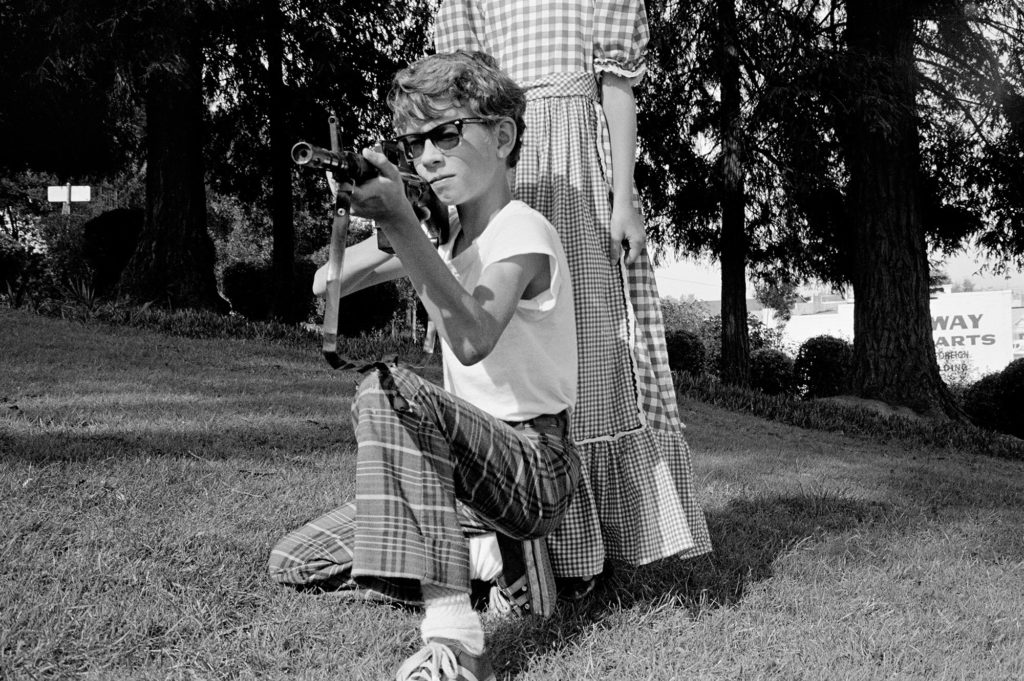

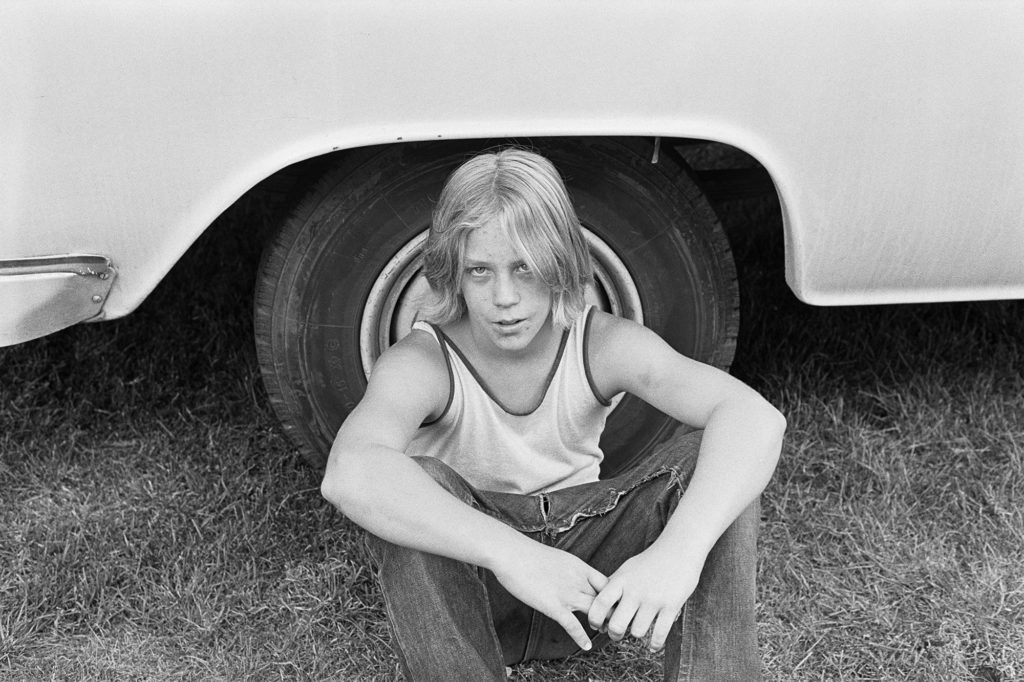

“I wasn’t seeing my experience,” Plumb said, when I asked her what motivated this particular group of pictures. None of the popular depictions of suburbia available in the 1970s squared with her upbringing. Born into a progressive household and raised in the shadow of the Cuban Missile Crisis, she didn’t relate to sitcoms premised on benign middle-class family dramas, such as Leave It to Beaver. Plumb’s interest in suburbanization aligned her with several photographers associated with New Topographics—a term coined around 1975 that encompassed conceptual work concerned with the built environment and its increasing impact on the (primarily Western) US landscape at the time. But the cool, formal approach and banal aesthetic that characterized that movement doesn’t correspond to Plumb’s way of seeing. Much of her imagery, by contrast, could be considered “hot”—a word that Larry Sultan, her teacher in graduate school, was known to employ when assessing student work. Warmth and affection radiate from her photographs of adolescents, whom she catches sneaking cigarettes, hanging out at the Walnut Festival, and killing time. Plumb was a teenager when she began making these portraits; she worked in close proximity to the kids, gained their trust, and portrayed them in tightly composed close-ups. She clearly identifies and sympathizes with their existence in the innermost circle of hell that is suburbia.

Plumb compounds the oppressiveness of California’s cul-de-sac ecosystem with allusions to the relentless, unforgiving sun. Expansive, bleached-out skies dominate images selected for the book’s front and back covers. The persistent cycle of droughts, wildfires, and heat waves is also on display, signified in ecological devastation—cracked earth, barren trees, dry hillsides devoid of vegetation. Forget the well-worn myth of California as Eden, Plumb’s work seems to say. This is the land of smoke and fire.

“For some kinds of people, the West is something of a paradise,” DeVoto wrote in his 1946 essay “The Anxious West.” “Even they, however, show symptoms of psychic insecurity.” The publishers Gregory and Rachel Barker keyed into this idea as they edited The White Sky in concert with Plumb, whose work possesses what Gregory described as a “psychic weight.” The observation that several unusual, unnerving themes emerged among the photographs Plumb shared with them, combined with Plumb’s reverence for books with a cinematic feel—Gregory told me that Plumb cited Mark Steinmetz’s languid Past K-Ville (Stanley/Barker, 2018) as a touchstone—ultimately led the Barkers to conceive of The White Sky as a suburban gothic in the style of Stephen King.

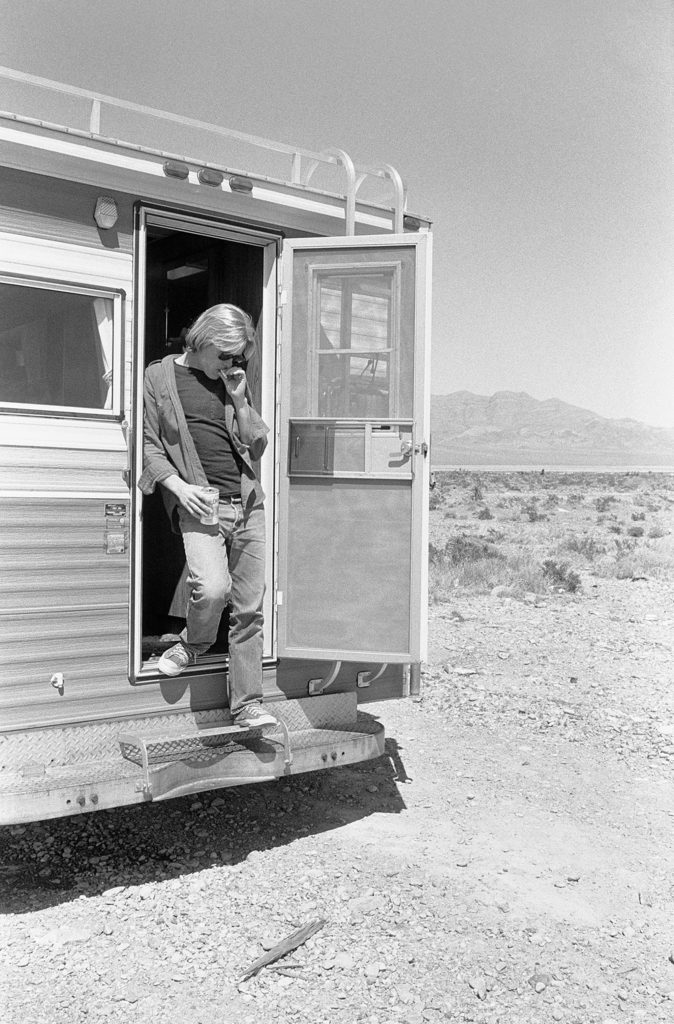

Premised on a stranger who gets stuck in a small town where an ominous incident takes place (its mysterious details never revealed), the imagined, unwritten plot of The White Sky hinges on the stranger’s realization that something is amiss in these new surroundings. Adults vanish over time, children form feral gangs and overtake the streets, and the land that surrounds this town appears increasingly uninhabitable. Design choices reinforce that storyline and sometimes operate like fear cues, devices that build suspense in films: the broken-down Pontiac gracing the book’s cover, for example, presages the arrival of the stranger and explains how he ends up stranded in the town. Bold intertitles that open the plate sequence impart a sense of drama, which crescendos with images of people standing around in a parking lot, staring up at a blank sky for reasons unknown. The calculated deployment of variant images and the repetition of certain subjects, from lit cigarettes to kids in Halloween costumes, produce a narrative as circular as the “loops and lollipops” patterns of cul-de-sacs.

In the middle of the book, an enviable backyard pool transforms into a remnant of civilized suburban life when alternate views reveal that a fire has claimed the surrounding property, leaving only the pool—complete with submerged patio furniture—and a chimney intact. Adding to these unsettling moments, the book was released in 2020, a year that played like a horror film: the largest wildfire season on record in California’s history took place, while the global COVID-19 pandemic broke out and prompted a mass exodus of city dwellers, many of whom fled to the suburbs. Plumb’s brand of horror seems derived from her eerily prescient vision as a photographer. In her mind’s eye, the future is a nightmare.

But the past is no less disturbing for Plumb. Her first monograph, Landfall (TBW Books, 2018), opens with a succinct statement that posits the consequential relationship between memory and fear: “I remember having insomnia for a time when I was 9 years old. My mother told me there might be nuclear war.” Recurring events—the frequent duck-and-cover drills at school, countless nights spent worrying about her inability to sleep—helped perpetuate the terror she felt at the time. This fear resurfaced while Plumb was in graduate school at SFAI in the 1980s, prompting her to ask a question that propelled her: “How do you photograph a fear?” By then, her concerns had expanded to encompass the wars in Central America, the AIDS epidemic, and the danger that the Reagan administration posed for democracy. She ultimately identified the threat of climate change as the inspiration for Dark Days, a body of work made between 1984 and 1990 that, years later, was published, albeit fractionally, as Landfall.

Plumb characterized her earliest efforts to document the effects of climate change on the landscape in the 1980s as like “trying to describe something that really hadn’t happened.” Plumb began to “people the landscape,” as she put it. She photographed children cavalierly playing with military-grade weaponry. She depicted her then-husband building model tanks in a bunker-like room. Other figures, many of them engaged in equally mysterious and foreboding activities, appear in Landfall, but everyone remains unidentified and, therefore, anonymous; Plumb frequently photographed individuals from behind, protecting their identities and heightening the strangeness of their presence. She also amplifies the anxiety coursing through these images with her calculated use of flash, which punches like a chord progression in a post-punk Clash track, while also gesturing toward a nuclear meltdown. (Plumb told me the nihilistic punk slogan “No future” aligned with her worldview back then.) Did Plumb succeed in photographing fear, or at least in capturing its timbre? Stephen King, when asked if fear was the subject of his fiction in 2006, said, “What I do is like a crack in the mirror. … an intrusion of the extraordinary into ordinary life.” If the threat of nuclear devastation constituted the point of origin for Plumb’s fear, then perhaps Landfall was the fracture that grew from it, an attempt to synthesize the chaos of feeling that had haunted her for years.

What she delivers in the space of that book is an imagined fallout: a molten globe discovered after a nearby house fire; a pier that has burst into flames; the charred remains of a lamp. Such images of conflagration and its aftermath present the American West as we expect it to look in the end, so it stands to reason that the work is sometimes described as “apocalyptic” or “postapocalyptic.” However, these terms obfuscate Plumb’s prelapsarian vantage point—she might anticipate the Fall, but it hasn’t necessarily taken place. Susan Sontag speaks to this idea in Illness as Metaphor (1978), declaring the apocalypse an “unreality,” and explaining it as “a permanent modern scenario: apocalypse looms … and it doesn’t occur.”

Living, as we do, in this state of suspended Armageddon, it’s worth asking what Plumb’s books have to tell us on their belated publication, decades after the photographs they feature were made. Things look different now than they did in the early 1970s, when Plumb started photographing suburbanization, and the adverse ecological impact of sprawl remained relatively invisible. Walnut Creek and other so-called “edge cities”—urban centers that radiate outward from the metropolitan area—in Plumb’s native Contra Costa County hadn’t yet been fully developed, let alone transformed into “economic atom bombs” (to invoke a term used by the writer Mike Davis) with the potential to devastate the economies of “inner-ring suburbs” closer to San Francisco. To document the threat posed by suburbia and the myth of the American dream, as Plumb did in the 1970s and published in 2020 in The White Sky, is to recognize American exceptionalism itself as a catastrophe revealed in slow motion.

Courtesy the artist and Robert Koch Gallery, San Francisco

The photographer Janet Delaney, who has known Plumb and lived in the Bay Area for decades, told me that Plumb’s photographs in The White Sky “were more like notes, a memoir that you recreate … by working with the images that you have at hand.” As Plumb tells it, she began to revisit her archive and scan old negatives only after her retirement in 2014 from San Jose State University, where she taught photography for nearly thirty years. But another indisputable factor involves Plumb’s age and gender—she is part of a generation of women photographers in the Bay Area (Delaney among them) whose work didn’t garner much attention until recently, and who didn’t necessarily seek out publication opportunities over the years. In 2018, the release of Landfall offered a welcome introduction to Plumb’s work, though its contents reveal, as the California Sunday Magazine photography director Jacqueline Bates (who published Plumb’s work the same year) noted, “Mimi’s California isn’t a welcome place for new beginnings.”

People “come to California to die,” Nathanael West wrote in his 1939 novel The Day of the Locust. To live in California is to believe that disasters are not only probable—they are inevitable. California’s seasons have names (“fire,” “dry,” “fog,” “wet,” even “mudslide”) that correspond to severe weather conditions with the potential to devastate the land. Its tectonic spine, the San Andreas Fault, could produce “the big one” at any moment, keeping Californians in perpetual suspense. Its extreme heat, the result of a harsh desert ecosystem and the reason for new climate catastrophes like hot drought, fuels the extreme fires of the Anthropocene that, according to Mike Davis, have “become the environmental equivalent of nuclear war.” There may be a perceived ease to life in California, but it belies a deep-seated unease. Residents here are instilled with an awareness of our precariousness—“beneath that immense bleached sky, is where we run out of continent,” Joan Didion wrote in 1965. With Plumb’s books and the imagination of disaster they reflect, she shows us how to inhabit that edge, time and again.

Mimi Plumb’s The White Sky was published by Stanley/Barker in September 2020.