A Brazilian Artist Finds Beauty in Hidden Revelations

Celebrated for her drawings and installations, Tadáskía’s photographs promote a new visual vocabulary about memory, property, and the Black family.

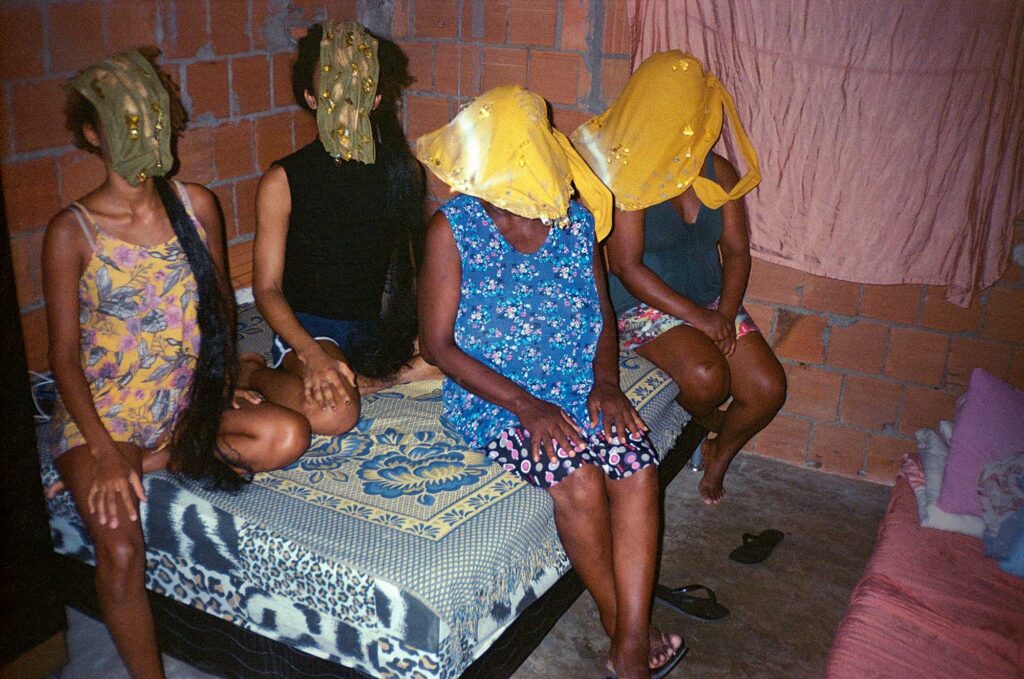

Tadáskía, Corda dourada com minha irmã Hellen Morais (Golden rope with my sister Hellen Morais), 2020

It was during the last Carnival, where Tadáskía said she had truly abandoned herself to the revelry for the first time, that she was bitten on her leg by a lacraia—what certain Brazilian regions call a centipede with a long body, a flat back, and numerous pairs of legs. They may or may not be poisonous.

I wasn’t familiar with the word lacraia before hearing this story, but I was struck by how it had become key to helping me describe Tadáskía’s practice. Tadáskía is an artist based between Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo in the southeast of Brazil. I have been engaged in a number of extended conversations with her, especially after the inclusion of her work Ave preta mística (Mystical black bird) in the 35th São Paulo Biennial in 2023, a large-scale installation currently featured in Tadáskía’s solo show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. During one of our encounters, Tadáskía used the centipede episode to explain what she describes as “apparition”: a moment of revelation in which one of its principles is believing that “something is going to arise; it is already arising, it already exists,” even if the moment of creation is an inoffensive centipede.

Tadáskía—who uses drawing, sculpture, photography, installation, and performance to express the enigmatic capacity of finding beauty from her experiences as a Black trans woman—has an ability to process an event as a “hidden revelation” by reading ordinary situations beyond their obvious meanings. In the case of the centipede, for example, between its most diminutive and extreme degrees of significance, the artist launched herself into a chromatic approximation of the chilopod with the figure of Exú—a deity in Afro Brazilian religions such as Candomblé and Umbanda. Due to Tadáskía’s long relationship with the Pentecostal church, she had not been intimate with his figure nor experienced his festival par excellence, Carnival.

Listening to Tadáskía and reflecting deeply both on my commitment to written history and her commitment to things created to be impermanent, I thought about the French writer Annie Ernaux, whom I had read on the eve of Carnival, and Saidiya Hartman, who writes about Black women’s ordinary lives and the monumental nature of their everyday experiences. Together, the two led me to consider the overlaps in the relationships between photography and performance, and between events, permanence, and disappearance. When I ask Tadáskía about how her photographs happen, she answers, “Things show up. And what I don’t know, maybe is in the notebooks.”

Lacraia (Centipede) is the title with which she baptized her 2024 notebook. At the time I began writing this essay, that notebook didn’t exist yet, but it was nonetheless happening, and ultimately appeared within another entitled Traveler’s Tote Bag—as Tadáskía would tell me. Tadáskía has often asserted that her work is grounded in composing with her eyes closed and in the relationships between doing and not knowing, showing and hiding, drawing and not seeing. The ideas and forms appear and reappear. They arrive through different channels. And just like the many images, orientations, instructions, sketches, and observations that have already begun to take shape in Lacraia, her works to show to hide (2020), Corda dourada (Golden rope, 2019), and Hálito (Breath, 2019) sprang to life through a similar procedure performed through notebooks.

In to show to hide, the mystery of apparition tells us about facing the issue of representation. “I believe that not everything can be revealed, not everything can be delivered,” Tadáskía says. “When you think about photography of Black and low-income people, there is always something to try to represent, to document, to bring an identity, an identification.” Certainly, that’s not what the artist is aiming for. With these photographs, if on one hand she feels the need to show the reality she came from—which on its face looks like a tremendously precarious context—then on the other the photographic language provides the chance to show what it itself is hiding. “It’s the moment when you are going to find a treasure, a certain spirituality of life as well as all of the conflicts that still haven’t been resolved,” she says.

Made with a Yashica 35mm camera that her father used during many childhood outings, to show to hide displays Tadáskía’s interest in the idea that something can appear in a photograph based on this belief in apparition. Because she stops looking at her notebooks after she creates them, the photographs arise from the pages of her imagination, almost like a prophecy. The apparitions aren’t rehearsed or literal. Her performative writing, which is often poetic and fantastical, plays a central role, coexisting in a syncretic way to allow the manifestation of expression to appear in different languages and converge in the construction of the apparition’s meaning. We can get even closer to this making-abstraction procedure in the work Ave preta mística (Mystical black bird), originally a book-length poem-drawing in pastel whose mystical words give wings to a multisensory world. As an installation, this world is animated with floor-to-ceiling charcoal drawings that embrace sculptures of cattails, where citric fruits, golden eggshells, sticks of bamboo, and colored powder gravitate.

Between notebooks and family albums, there is a golden thread that ties, connects, sews, stitches together and, as Tadáskía says, “redistributes the center” in many of her works.

As she performs with and against the camera, Tadáskía often invites the presence and participation of members of her family. The epistemologies of escape and the affective ancestral repertoire fill her cognitive framework. In to show to hide (2020), Tadáskía creates a family of sculptural objects that are worn and performed by her mother, Elenice Guarani, and her father, Aguinaldo Morais. Their names are Zumbidas (Buzzings), Rastejantes (Crawlers), Rabos (Tails), Trepadeiras (Creepers), and Gruda-gruda (Sticky-Sticky). These wearable sculptures end up camouflaging or masking the expected image of everyday Black life. The play and the dialogue between two families—human and sculptural—show and hide the ordinary and the alien in an interaction in which the family appears not only as a theme within the work, but also as the protagonist of a broader artistic project of redistributing abundance.

Between notebooks and family albums, there is a golden thread that ties, connects, sews, stitches together and, as Tadáskía says, “redistributes the center” in many of her works. This redistribution of resources as an aesthetic methodology and ethical procedure (a perspective recurrent in the practices of many other Black and Indigenous artists) recalls Stefano Harney and Fred Moten’s affirmation, in “Fade of the Black Family Photography,” an essay in the 2023 book What Matters Most: Photographs of Black Life (2023), that “of all the art forms photography is the one most susceptible to a discourse of rights, for good reason. And the right it most invokes is the right to ownership.” Harney and Moten’s positioning of photography in relation to property resonates with the compulsory but generative state of dispossession, the expropriation of Black life, and the relationships between the subject and object “that resists the ends of gaze and image,” they write.

The fundamental ethics of Tadáskía’s photographic project include sharing any earnings with the family members present in the images, as well as undertaking a range of economic reparations projects. As such, the photographs seem to confirm a family pact that ironically says, “We can have some ownership, even being owned.” The artist herself has said, “On January 10, I invited my family and friends to appear at 1 p.m. to eat a golden meat and a black juice . . . I served the golden meat and the black juice into the hands of each person using a wooden spoon. After eating, we put away the towel and the objects for our second apparition. On the same day, at 4 p.m., we appeared in front of the door of Cavalariças. And so, we heard people saying olha o passarinho [watch the birdie] as they photographed us and we rolled our eyes. Each person in their own time.”

Family pictures can fade or be abandoned—or they might not exist at all. In one group of photographs from 2020 called Corda Dourada (Golden rope), Tadáskía considers the economy of visual ownership and the relationship between owning and being owned. Here, the rope in the title is seen connecting various figures. For Tadáskía, the past is the present as well as the history of Black existence. The rope revealed itself as an apparition, she tells me; fortune can’t simply be summed up in material measurements. The performance, then, arises as a gesture that expands reality’s objective need: to realize an act in which gold is ritualized and is prophesied as an image for the future. Even if framed by the bricks of an unplastered home or by an architecture that structures poverty, family is a commodity that resists its own photographic objecthood and competes with history’s own reproducibility. Tadáskía’s photographs promote the creation of a prolific visual vocabulary in which the relationship to memory and property is remade under her own terms.

Perhaps this change in perception and scratches of humor and irony are among the difficult gifts that Moten and Harney speak of in relation to the image of the Black family. “Existence insists upon this blur of wound and blessing,” they write. “It’s the aspiration of our dying breath, the substance of being unseen in always being seen, which, secretly, selflessly, we see with ourselves, not seeing our selves but seeing something more in seeing with, as if seeing with were all, as if all were just that practice, just how we do on Sunday evening, evidently.”

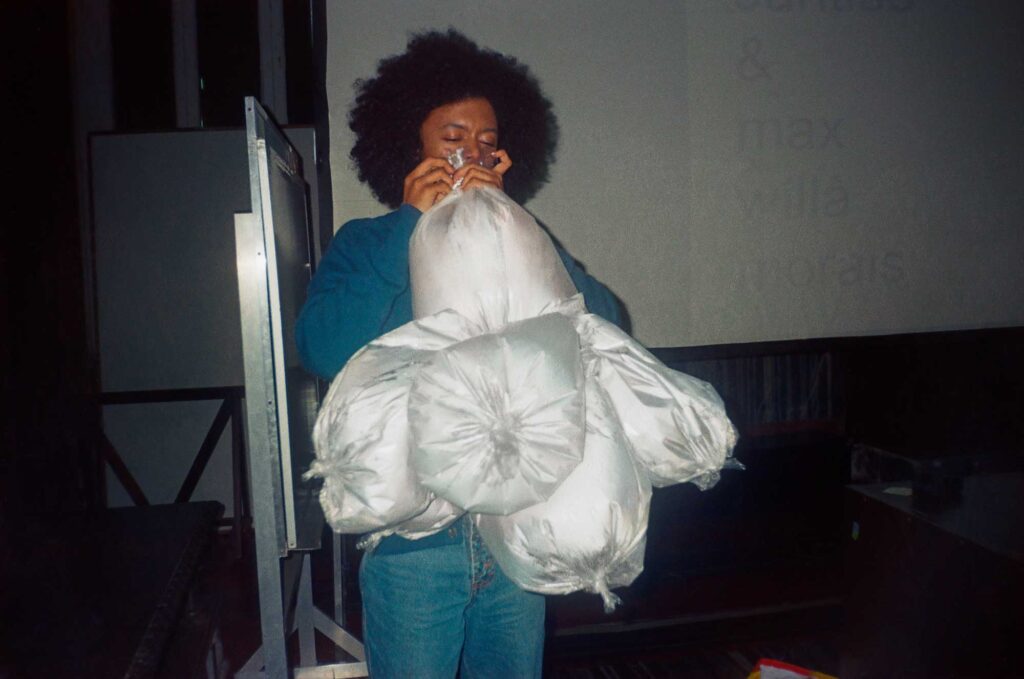

It’s also with a sigh and a breath that Tadáskía meditates on the brutal event that lit up the news in 2018: the murder of Matheusa Passarelli, a twenty-one-year-old student, artist, and LGTBQ activist, in Rio de Janeiro. After days without explanation of her disappearance, at 10 a.m. on May 30, Tadáskía built a small fortress to hide in. “I am wearing a red dress in homage to Matheusa Passareli,” the artist recalls. In her performance Atrás do muro (homenagem à Matheusa Passareli) (Behind the wall [homage to Maltheusa Passareli], 2018), Tadáskía passes a plastic bag through a hole in a wall of cement blocks that she built; she fills, empties, and breathes into the bag as it is wedged into the wall. Passareli is family, and this breath of life appears in different scenes. Tadáskía’s work becomes a photograph of a family that was destroyed, dispossessed of its self-image. Or could it be another kind, our kind, the kind considered possible for a Black family album?

Hálito (Breath, 2019), which includes a photograph of Tadáskía puffing into plastic bags melted by fire, unfolds in the kitchen of the artist’s home with her mother, her father, her grandmother, aunts, and cousins. It is the duration of a life that creates this portrait. The framing of the photograph, Harney and Moten write, “is commissioned against but also under the terms of a contract of civil butchery. Held out, held back, shard, shielded—the chemistry of stolen moments is our true and terrible and beautiful black share.” Hálito may be what the artist calls “an elementary exercise in vitality” or “a temporary meeting that wilts.” Harney and Moten continue: “This chain of viewing (looking, looking like, seeing with, seeming, unseaming) is a chain of handing. There’s violence in being held on the verge of being hidden. Being treasured is all but being lost. Nothing found in being sought. Common breath is gone and we can’t reconstruct it. And, anyway, what’s this presumption of family, and its rights and its brokenness, all of which are confirmed in the snapshot’s uncanny, untimely career? Can there be such a thing as a Black family photograph? Should there be?”

All photographs courtesy the artist and Fortes D’Aloia & Gabriel

The breath of life of Tadáskía’s photography, as a whole itself a sweaty and hot photography, stems from her insistence on the animating power of transformation and resistance, and through her awareness that this is the language of perception that we possess in order to be possessed. Between what Harney and Moten call “the interminable flash, the undefinable moment of being stolen,” and the fact that “we are disappearing,” the Exú-like centipede renews the artist’s commitment to believing that “not all dangers are lethal,” and in our own belief that apparition is an act of faith. We need to take stock of shallow and banal images. I return to the prophecy of the artist’s notebooks: “We belong to the family of the Mystical Black Birds. We are also known as the Enchanted Chickens. Inspired by Sankofa. Friends of Magic.”

“All the images will disappear,” Ernaux writes. Will there be someone who recognizes us?

This essay was originally commissioned by ZUM magazine, published by the Moreira Salles Institute in São Paulo. Translated from the Portuguese by Zoe Sullivan.