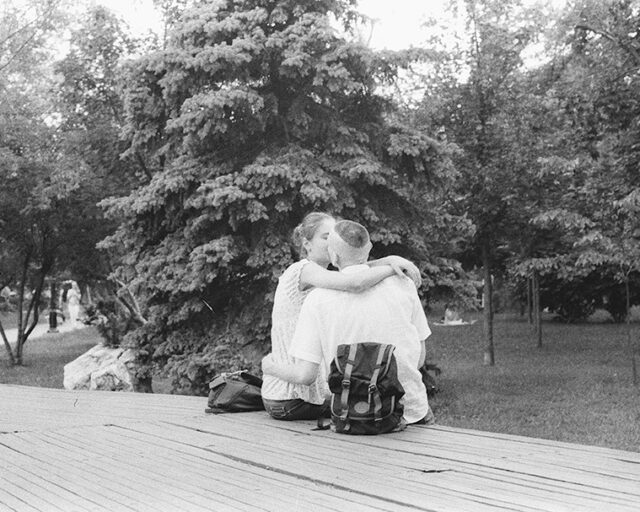

Daria Svertilova, Portrait of artist Krystyna Melnik in her studio, Kyiv, 2023

On a three-week trip to Ukraine last spring, I experienced the innovative and engrossing exhibition Essential Goods, which felt like a labyrinthine voyage of discovery. It featured 166 photographs by twenty-four younger Ukrainians, the “next generation,” according to curators Isabella van Marle and Sonya Kvasha, of photographers and lens-based artists. This was a relatively rare and extremely welcome exhibition in Ukraine, where the art world has long skewed toward painting and sculpture.

All of the photographs in Essential Goods, which was on view briefly in late May through early June, were made during wartime, many since Russia’s full-scale invasion, on February 24, 2022, and others before. The earliest images dated from 2014, when Russia and its proxies “temporarily occupied” (a term employed all the time in Ukraine) Crimea and parts of both Luhansk and Donetsk in the East. There was an expansive range of subjects, themes, and sites: a bullet-pocked wall in Kyiv, partially demolished buildings, and sandbags in a pile; vibrant nature and a fresh cemetery; youth culture and family life; alienation and memory, loss and connection; among numerous others. Flat-out talent abounded and deep feeling was palpable in this collective, multipart portrait of contemporary Ukraine.

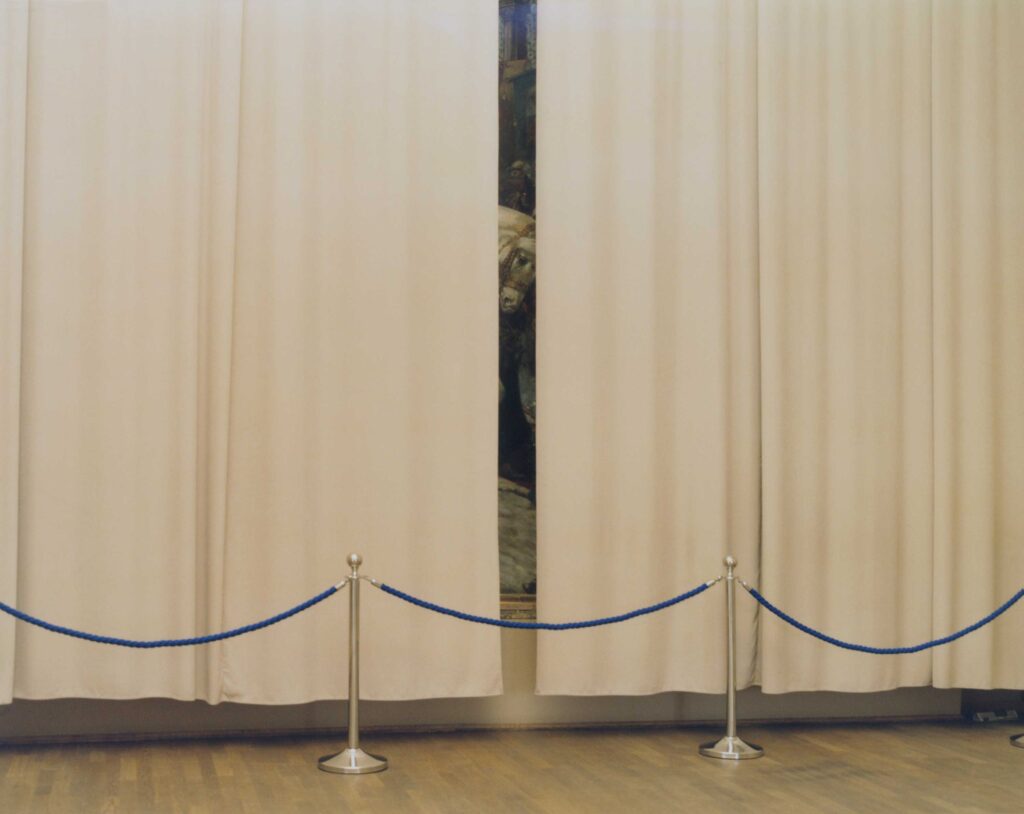

The exhibition’s setting was the glass-walled Pavilion of Culture, in a massive and imposing Soviet-era complex. In 1967, the Pavilion was constructed as an exhibition space, also to celebrate the coal mining industry in the Ukrainian SSR. Soon after the full-scale invasion, it was repurposed as a warehouse for humanitarian aid, while still presenting exhibitions. That a building so emblematic of Russian domination and oppression is now being utilized to assist Ukrainians suffering from renewed Russian aggression is striking. Novel architecture by the Ukrainian firm FORMA allowed for photographs to be displayed alongside boxes of aid supplies.

The exhibition showcased the vitality, intensity, and vision of Ukrainian photographers. (Russia has been suppressing, imprisoning, and murdering Ukrainian cultural figures for centuries.) Near the end of the final class in his Yale University course “The Making of Modern Ukraine” (which is available online), Professor Timothy Snyder quotes the contemporary Ukrainian poet Yuliya Musakovska: “I thank all of the Ukrainians who are continuing to create in times of war.” Essential Goods was full of such creators.

Back in New York, where I live, I met with three of the participating artists—Vladyslav Andrievsky, George Ivanchenko, and Daria Svertilova—on Zoom or WhatsApp. Ivanchenko photographed Izyum’s residents; the city was brutally occupied by Russians and later liberated by Ukrainian forces, who discovered a mass grave full of civilians in a forest. Svertilova made distinctive images of scenes especially significant for her in post-invasion Kyiv and Hostomel, the site of the first major battle between Ukrainian and Russian forces. Andrievsky’s pre-invasion photos of gray and alienating Soviet-style, high-rise apartment buildings on the outskirts of Kyiv show the young adults (his peers) living in that environment. In our conversations, which have been condensed and edited for clarity, they each spoke about how the war has changed their lives and work, and how Ukrainian identity itself has been transformed by the conflict.

Gregory Volk: Could you speak about your work that’s in that exhibition, where it came from, what your concerns and motivations were?

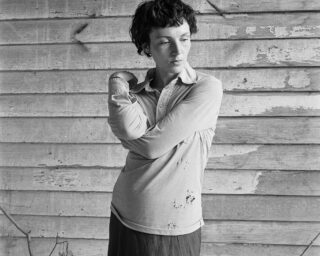

Vladyslav Andrievsky: I was showing my main series at this moment, it’s called District (2017–22). This is a series about the outskirts of a big city. Most of the buildings here are constructions from the Soviet era. So, they are buildings of economic changes, of new ideas, but they are not really comfortable. They are concrete, and they became even more raw and dull after the Soviet Union collapsed. And now, this place feels quite depressing. But despite that, many young people were born there, grew up there, and still live there, and I feel a certain tension between these faceless buildings of the outskirts, and the young generation growing up in the internet reality. We are scrolling Instagram, we see a lot of beautiful places, we see that we are the same as our peers in England or the US, but we have a different environment. That is why I was interested in outskirts and in the young generation, and how we can dream about something different. So, it is about a tension between this depressive, concrete, and gray environment and a young generation with bright minds and hearts.

Daria Svertilova: The series that was partially presented in Essential Goods was my reflection on the first year of the full-scale invasion. I was working on a long-term project before the full-scale invasion started, and then, all of a sudden, nothing was making sense to me. I was abroad at the time. For seven years, I have been partially living in Paris. Now, I can say that I’m based between two countries, because I have been returning to Ukraine constantly. I spend half of my time here and half of my time in France.

During the first month of the invasion, I was overwhelmed with journalistic images, and I was questioning my practice, my place as a photographer in that context, whether I was ready to do journalistic photography, or if I needed some more time to reflect and create other imagery. When I came back to Ukraine after the invasion, it was August 2022, so I started to take pictures that were kind of like what everybody was taking. I wanted to go to liberated towns around Kyiv. I wanted to photograph the remains of the destruction.

And then, throughout the first year, between 2022 and 2023, I was focusing on things that I found different every time I came back. I called the series Irreversibly Altered because everything was kind of altered to me. I constructed it around a notion of a dream, because since the full-scale invasion started, I was dreaming a lot about the war.

It doesn’t have the classic narration of a documentary series. It’s really like a puzzle of impressions of some parts of the reality that I would find every time I would come back. For example, in December ’22, there were blackouts. In summer, there were still ruins in the Kyiv Oblast, but then they were quite quickly cleaned away. I also photographed some women members of the military. My series, it was really like reactive photography. It was some kind of sublimation of the things that I was living through.

George Ivanchenko: I’m not an art photographer. I work with reportage. But for this exhibition, I sent the pictures of people who were living together, in a building, during the occupation of Izyum. I just love these people; we speak a lot. I lived there in a flat because I was working with volunteers. I started to make pictures about these people. I see the simple soul of the East of Ukraine and in Izyum it’s special, it’s not like in Donbas, it’s not like in Kharkiv.

Volk: How did you come to photography? Did you first explore other mediums, or have you long known that photography is your calling in art?

Andrievsky: First I wanted to be an artist. I used to draw, but then I discovered photography when my mother gave me a camera and a few rolls of film. From that point, I started to document my life during summer camp. That’s how I got involved in photography. I started to buy some photography magazines, to watch some documentaries. Later, I met Viktor Marushchenko, a Ukrainian master of photography and a great teacher. I was studying in his photography school for about three or four months, and that experience changed me forever. That was a very, very big influence on me as a person and as a photographer. Unfortunately, Viktor died in 2020, and I think this was a huge loss for the future of Ukrainian photography.

Svertilova: I took painting classes as a kid. I was a teenager when I started trying to do photography, and it was a kind of hobby. My grandfather gave me this old Soviet film camera, and I was also experimenting with just taking pictures on film. Basically, it all started at school, and at some moment, I was taking pictures of my classmates and they were encouraging me to continue. And progressively, I started to take photography more seriously. I met some people older than me who would advise me about books, some photographers to look at, and that’s how it developed.

When I was 21, I entered an art school in France, and basically, since then, I had access. I feel quite privileged to have access to photography events, to exhibitions, to bookstores. And it’s true that in Ukraine, we are quite limited with all this photography market, let’s say, because photography is not really taken seriously here. It is starting to be taken more seriously, but we’re not very supported by institutions like it is in Europe, or in the US.

Ivanchenko: I had been studying journalism for one year in Lviv when the big invasion came. The first day I understood, I can do this now or never.

Volk: How has the war affected you personally and as lens-based artists? Have your work or motivations substantially changed? I’m guessing that none of you ever imagined you would be wartime artists.

Svertilova: It’s a big, big question. We have been speaking about it with a lot of friends and we’re still speaking about it. We are Ukrainians, we were born here, raised here, and even if some of us are working abroad, partially, we still identify ourselves as Ukrainian artists. So, basically, all the work we’ll do, it’ll be war-related in some point.

The full-scale invasion, it stole a lot of things from us, but it also stole our ability to speak about other non-war-related subjects. The war has been taking place since 2014, but still, we had more freedom to speak about some things that were, maybe, less tragic, let’s say. Now, it’s so overwhelming.

I believe that art is political, and I believe that the work we do is political, because we witness something, we work with the medium of art photography or documentary photography. We’re not making collages, or completely abstract things, so we work with the reality, and the reality is tragic. I believe that my personal work changed. I don’t see now a possibility to do work that is completely un-related to the invasion, or to politics somehow. That can be tough, sometimes, because I don’t feel like I’m able to do the work that is purely aesthetic.

Andrievsky: It is also quite tough for me as well, because I have not been practicing photography since February. I don’t understand how to react to this reality today, as I see that a lot of works that artists are doing now in Ukraine, they are more documentary reflection of reality. And I’m not really sure that I want to be a documentary photographer.

At some point, I decided just to live through this experience, and maybe, in the future, I will try to say something, with distance. But, of course, I take photographs on my phone and I somehow experiment with Xerox, because I like this filter that Xerox does. It is like broken images. It is not smooth, it is not perfect, and it somehow reflects and shows this current time.

Ivanchenko: Gregory, I can’t say I’m an artist.

Volk: Just wartime photographer?

Ivanchenko: Yes, it’s like that. The war makes faster all the processes in your life and all relationships with people. You change many times during these three years. You want to find something, you learn, you do stupid things, you study, in your way. In the first week, I went to Kyiv from Lviv, and for one and a half years, I didn’t have a room, a house, someplace where I stay and keep all my things. I have everything in a bag, my camera, and then it’s another city, it’s the front line. It’s south, it’s east. You just live somewhere, sometimes without money. You don’t know exactly what you do, but you just feel it and you understand. It’s a lot of experience, a lot of really important moments with this big pain.

Volk: The first night I arrived in Kyiv, Russia sent fifty-three Iranian-made Shahed drones and five missiles, including at Kyiv, and there was a big explosion not far away from me. And then, the next morning, I went to your innovative show, in which humanitarian aid was exhibited alongside your works. And I understand that the Pavilion of Culture, since the start of the full-scale invasion, has been used to store and distribute humanitarian aid. How did you feel, as artists, as photographers, showing in that context?

Svertilova: I knew Isabella van Marle, the curator, from a Pictures for Purpose fundraiser, and she contacted me to ask if I was willing to participate. Initially, she planned to organize a show in Paris. And then, she said that the show would be in Kyiv. There are not lot of photography exhibitions taking place in Kyiv right now. The exhibitions that are there are mostly photojournalistic ones, and art photography is very underrepresented, in my opinion. It was right to use this space, because it’s like an old Soviet pavilion. The humanitarian aid was part of the context, because we were speaking about war-related subjects, even if they’re non-explicit. I think I wouldn’t like to see these pictures in a white cube gallery space. For me, the choice was right for the time we showed this work.

Andrievsky: I agree with Daria, because it is how everything is now, it couldn’t be separated. We live in this time where everything is all together—war, life, death, and so on. It is a reflection of today.

Volk: I’m wondering about the role of artists in Ukraine. One thing I know is that artists, poets, and writers have long been essential for Ukraine and Ukrainian culture, and have often suffered greatly at the hands of Russia. But right now, there is resurgent interest in Ukraine, in contemporary art and literature, and I hope this extends to photography. Can you talk a little bit about your audience, or what you want your works to do in the world in terms of connecting with other people?

Svertilova: For me, personally, it’s horrible to say, but the only positive thing of what’s happening is that all foreign countries, finally, started to distinguish who are Ukrainians and who are Russians. What is happening now is very brutal process of decolonization. Basically, we had the same cultural context with Russia for a long time. I remember, when I was a teenager, we would watch Russian TV series because we had Russian TV channels.

It’s crazy how tricky it was that so many people were identifying themselves with a Russian context. And now, we realize that it’s totally different, and it was artificially-implemented during Soviet times. And also, there is this complex of inferiority, that we were growing up with the idea that Russian language is better. It’s equivalent to you being educated that Russian culture is better, that everything is better.

What’s happening now, it’s very complex. The war is not just about life and death. It’s also about moral choices and a lot of cultural processes taking place at very accelerated speed. In a very, very short amount of time, like in three years, we are completely changing our mind, and understanding who we are.

Volk: And art is an important part of that.

Svertilova: Absolutely. In this context, I would like to bring attention to some things that matter to me through my own prism, because I’m not a war photographer. I don’t see myself going to trenches with soldiers and taking journalistic pictures. I don’t feel that’s my place, because there are so many people who are doing it much better than I would do.

I’m more in slow documentary photography, processing things and speaking to people and also living through all this experience. For me, photography is always about this double-sided, let’s say, position, like you are supposed to be a bit insider to understand the context and to treat the subject in the right way. But also, you are supposed to have this distance. I’m trying to balance between these two because I’m trying to reflect on things which I’m a part of, but at the same time, I try a bit to take a step away to understand what’s it all about. And sometimes, it’s overwhelming.

Andrievsky: I also think that it is good for us that we investigate a lot of Ukrainian culture now. There are not many exhibitions of photography, but we have a lot of art exhibitions of the masters of earlier times. It is really important to be an artist, and I think we should not just be artists, but be Ukrainian artists.

We need to be supported by the institutions. We need education programs for the young generation. Unfortunately, our universities are very Soviet. They have a very strict vision of what is beautiful, what is not beautiful, what is right, what is not right. We need new programs, new visions, new names. It’s very important to talk about Ukraine abroad and about culture, but it’s even more important to do exhibitions and programs here to raise and educate a new generation who will know what it means to be Ukrainian and what Ukraine is.

All photographs courtesy the artists

Volk: George, what is your role as a photographer in Ukraine now? You took photographs in Izyum when it was occupied. The Russians left a mass grave, you’re photographing people who lived there, who lived under occupation and now are liberated, so your photographs are important.

Ivanchenko: It’s important because you can give information via your pictures, and they’re also part of history. People really see this and they will think about it.

Essential Goods: Ukrainian Photography Now was on view at the Pavilion of Culture, Kyiv, Ukraine, May 23–June 6, 2024.