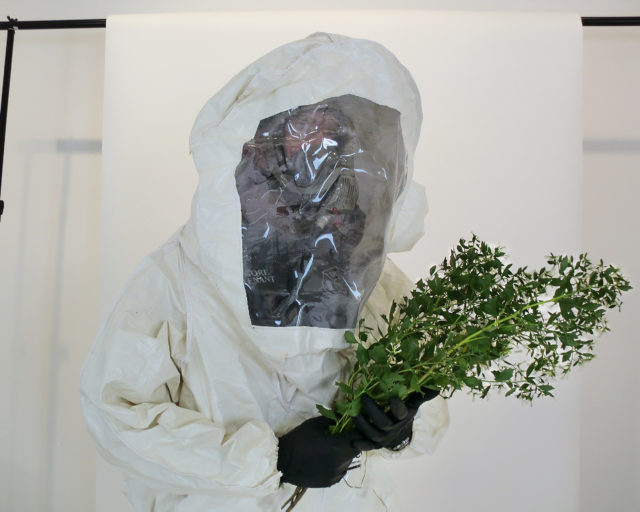

Tony Oursler, Phase/Trans, 2019–22

Courtesy the artist

Water coursed through the opening weekend of the 2022 FotoFocus Biennial in Cincinnati, Ohio—visually and metaphorically. Established in 2012 as “a month-long celebration of photography, film, and lens-based art,” with dozens of exhibitions and events in Greater Cincinnati, Northern Kentucky, Dayton and Columbus, Ohio, this is its first iteration since the pandemic. My visit started with a water-themed exhibition by Tony Oursler at Michael Lowe Gallery titled Crossing Neptune, which features dozens of works from the artist’s archive: photos, videos, objects, and three of Oursler’s video sculptures that together express the complex mythic, religious, elemental, and ecological aspects of H2O. The display is as generously haunting and witty as the chattering, animated objects for which the artist is known. With half of it occupying a subterranean gallery bathed in a soft blue light, the experience is immersive.

Collection of Tony Oursler

FotoFocus takes place at various venues and touched off with a two-day symposium at the beginning of October. The latter concluded with a keynote lecture by the filmmaker Jeff Orlowski-Yang, who spoke about his documentary Chasing Ice (2012), which follows a group of photographers who use groundbreaking time-lapse cameras to capture the speed and extent of melting glaciers due to climate change. It was a chilling presentation, especially when Orlowski-Yang showed horrifying yet sublime clips of skyscraper-sized ice blocks collapsing into the sea. The talk generated an incisive audience question: “I’m an artist, but after seeing what you’ve captured on film, it seems like nothing else matters. How can we go on making art?”

Courtesy Robert Mann Gallery

Many of FotoFocus’ exhibitions, panels, and artist talks tiptoed around that question, with works located between aesthetics and activism. The Biennial’s title, World Record, encompasses the dynamic, suggesting the buoyant popularity of the Guinness Book of Records while alluding to that term we’ve heard so often the last few years: unprecedented. During the weekend of the opening, Hurricane Ian was pummeling the southwest coast of Florida. With wind speeds placing it just shy of a Category 5 storm, it was one of strongest to strike the US. Meanwhile, California’s water year, used to measure hydrologic records, concluded on September 30, and the state’s Department of Water Resources declared the drought from 2020 to 2022 “the driest three-year period on record.” Few of us would be surprised if these records break before the next Biennial.

This backdrop might suggest the Biennial would comprise a series of dour exhibitions, but FotoFocus exudes visual verve and curatorial energy. The Oursler show was a heady, intoxicating brew of pop-culture references and mysticism: the artist’s archive includes anonymous vintage photographs of hydrotherapy, mermaids in makeshift costumes, the Loch Ness monster, wishing wells, beached-whale carcasses, and historic floods. There is a vitrine holding ornate bottles of holy water. Kitsch mingles with metaphysics in a balance necessary to survive contemporary crises.

Courtesy the artist and Mendes Wood DM, São Paulo/Brussels/New York

Land and sea both figure in FotoFocus’ centerpiece exhibition, On the Line: Documents of Risk and Faith at the Contemporary Arts Center. Curated by Harvard Art Museums photography curator Makeda Best and FotoFocus artistic director Kevin Moore—who also organized the Oursler show—On the Line uses the line as a metaphor for something that might be crossed, inviting us to assess risks and rewards both personally and politically. This approach offers plenty of opportunity to include works related to borders, including by An-My Lê, Paulo Nazareth, and Jim Goldberg. Borders are often conceptually liquid, as Dara Friedman makes plain in Government Cut Freestyle (1998), a silent 16 mm film of young people gleefully jumping into the ocean from a pier in Miami Beach. The exact location, identified on the wall label, is South Pointe Park, a spot home to the “government cut”: a manmade shipping channel.

During his symposium conversation with Best at Memorial Hall, on October 1, Moore acknowledged Friedman’s piece as a curatorial catalyst for the exhibition and noted its emphasis on human play and sociopolitical complexity. A similar performative precociousness is conveyed in the first works we encounter in the show: images documenting David Hammons and Dawoud Bey’s infamous Bliz-aard Ball Sale (1983), in which Hammons sells snowballs on a street corner, and Francis Alÿs pushing a hefty ice block through Mexico City in his equally famous Paradox of Praxis 1 (Sometimes Doing Something Leads to Nothing) (1997). These performative acts of futility reminded me of Orlowski-Yang’s lecture, in which he noted that in the face of collapse, you cannot sit complacently: doing something is an expression of hope.

Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

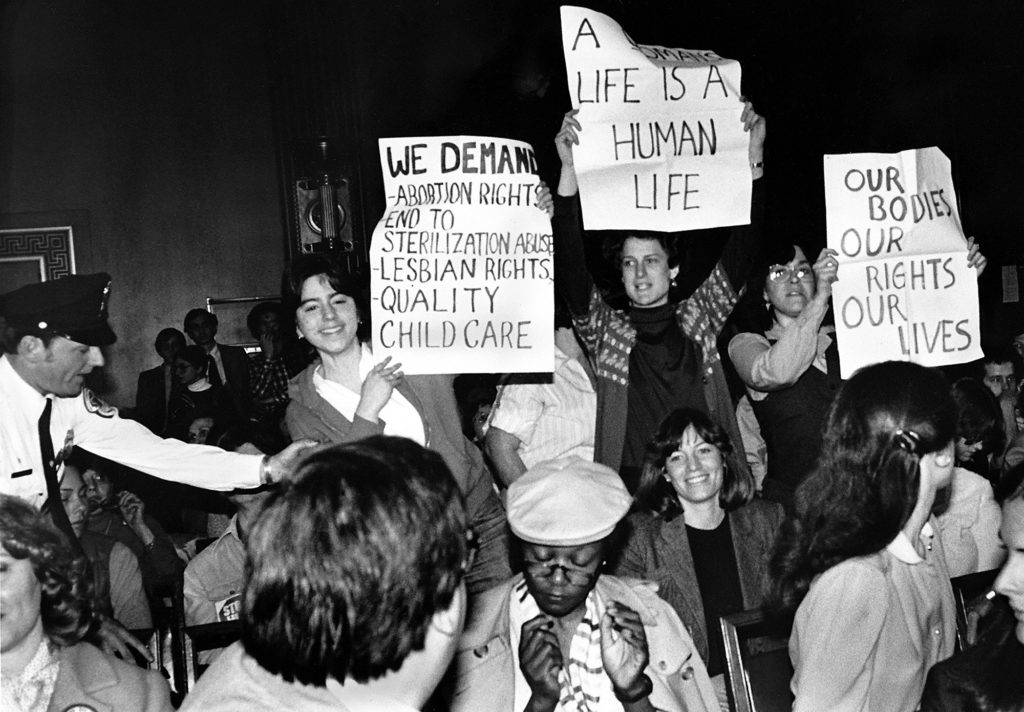

Action is very much the operative word in the exhibition Images on which to build, 1970s–1990s, a compelling look at historical activism by queer and trans image-makers also on view at the Contemporary Arts Center. Curator Ariel Goldberg features six artists and group projects that are as much about forging community and disseminating important information as they are about making art, and as such offer a counter to our view of social media as a political catalyst, albeit an illusory one. Diana Solís’s photos form an archive of Chicana feminism in the 1970s; Lola Flash’s vibrant, unearthly color studies are rooted in club culture and AIDS activism; and The Dyke Show (1979) by JEB (Joan E. Biren) is an astounding compendium of lesbian imagery and ideas that the artist presented in person as a slideshow, at venues across the United States. The human connection attached to such projects, among others in the gallery, is important to reconsider in the age of facemasks, quarantine, and rising queer- and transphobia.

Courtesy the artist

FotoFocus exists in this spirit of bringing people together to discuss the implications of images. I, for one, would not have experienced Orlovsky-Yang’s frightening and vital work about climate change had I not traveled to Cincinnati. Nor would I have heard him say that despite the enormity of the crisis, he still holds hope for change—and the ability of artists to depict and inspire it.

World Record, the 2022 FotoFocus Biennial, continues at various venues in Cincinnati, Ohio, through 2023.