Russell Lee, 4-H Club members give their club pledge, Mrs. Faro Caudill, who is second from end on rear right is their leader, Pie Town, New Mexico, 1940

In April 1941, Russell Lee traveled to Chicago with fellow photographer Edwin Rosskam to document life in the “Black Belt,” an area of predominantly Black neighborhoods on the city’s South Side. The photographers were on assignment for the Farm Security Administration, the New Deal agency that sought to combat rural poverty, and became famous for its project to photograph the struggles of impoverished Americans. Escorted by Richard Wright—whose landmark novel Native Son had been published a year prior—the pair spent three weeks visiting sites throughout the South Side, including public housing, schools, grocery stores, hospitals, nightclubs, and churches.

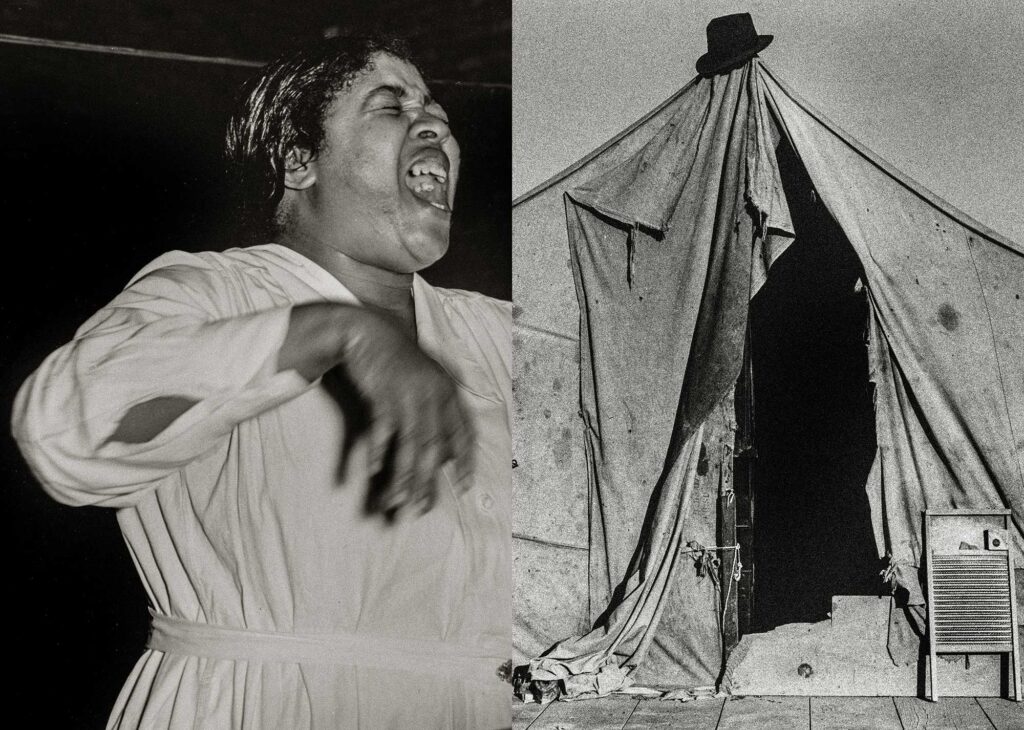

At the historic Langley Avenue All Nations Pentecostal Church, Lee took one of the most captivating images of his career. A church leader, a Black woman, stands at the pulpit dressed in white robes, testifying before the congregation. She is animated, eyes closed, head thrown back, mouth open mid-speech, right arm hovering as if steadying herself against some unseen force. The photograph radiates a sense of spiritual surrender. It tells a different story than the images most often associated with the FSA: Dorothea Lange’s portrait of Florence Owens Thompson (the “Migrant Mother”), for instance, or Walker Evans’s photograph of Allie Mae Burroughs, iconic portraits of the twentieth century that elide as much as they illustrate what it looked like to be poor in America during the Great Depression.

By the time Lee arrived in Chicago, the FSA, under the aegis of program administrator Roy Stryker, had begun to document poverty in urban centers. A master propagandist, Stryker understood that the hard-luck, Dust Bowl imagery the agency had been producing since the mid-1930s was sidelining other narratives. What was the experience of the millions of Black Americans who had moved to northern and midwestern cities from the rural South during the First Great Migration? To fulfill the FSA’s goal of introducing “Americans to America,” the scope of the images expanded.

Lee’s photograph of the Pentecostal leader appears in the opening pages of Omen: Phantasmagoria at the Farm Security Administration Archive, 1935–1944, which reimagines the project of the FSA through a study in radical contrasts. Edited by Mexican designer León Muñoz Santini and Colombian photographer Jorge Panchoaga, the book draws on images from the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints, and Photographs of the New York Public Library to feature work by eight of the FSA’s twelve full-time photographers: Russell Lee, Dorothea Lange, Ben Shahn, Walker Evans, Carl Mydans, Arthur Rothstein, Gordon Parks, and Jack Delano.

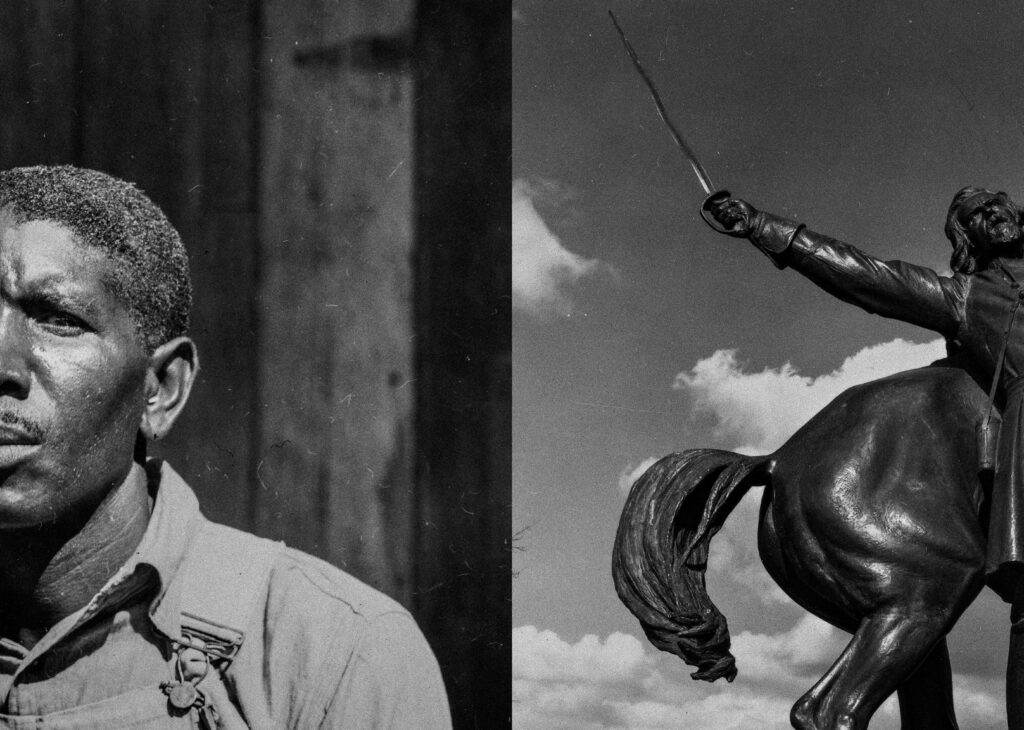

A phantasmagoria is a succession of real or imaginary images, as in a dream. Omen fully embraces this concept, both through its sequencing, which creates a loose, unsettling narrative, and through particular pairings that suggest oneiric fictions, possession as much as dispossession. Lee’s aforementioned photograph, for instance, is juxtaposed with the solitary tent of a pea picker, photographed by Dorothea Lange two years earlier in California’s Imperial Valley. Taken nearly two thousand miles apart, the pictures collapse time and distance, together conjuring evangelical tent revivals and faith healings.

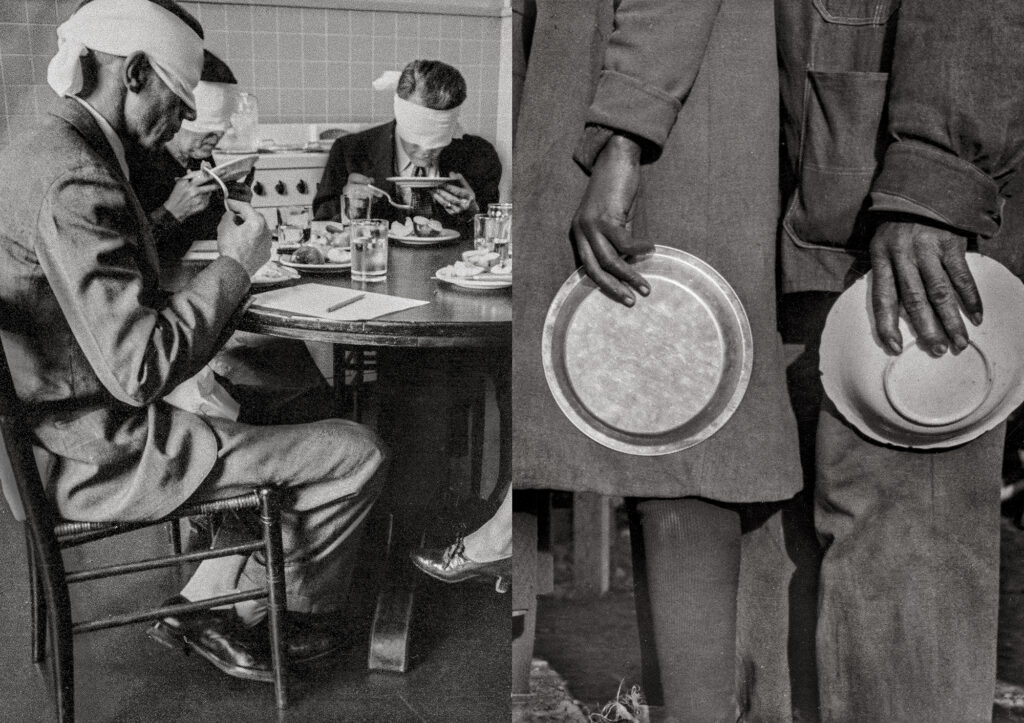

Another spread pairs two photographs taken in 1935 by Carl Mydans. The first, shot at the Department of Agriculture in Beltsville, Maryland, depicts several blindfolded men and women—all white—taste-testing meat while seated around a kitchen table. Opposite is an image taken in Forrest City, Arkansas, which shows a Black man and woman waiting in line for food at a camp for flood refugees. The photograph is cropped to show only their torsos and left arms, empty plates in hand. The striking, ominous racialized contrast illustrates the chasm between blind abundance and true need.

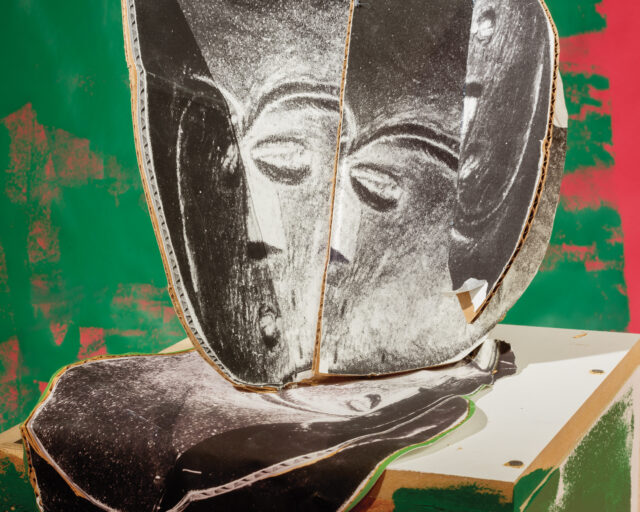

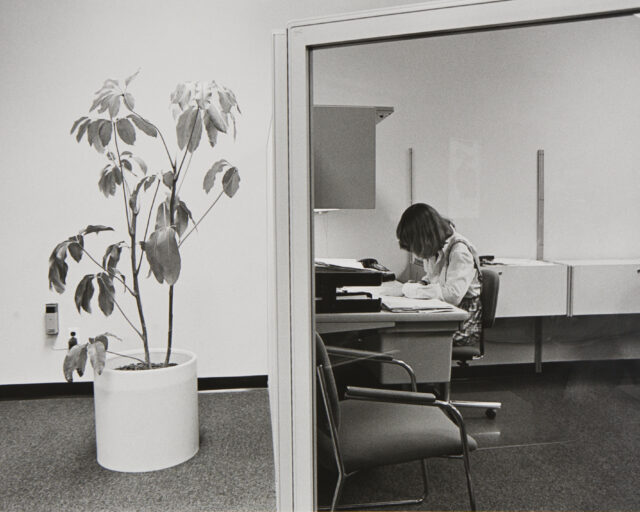

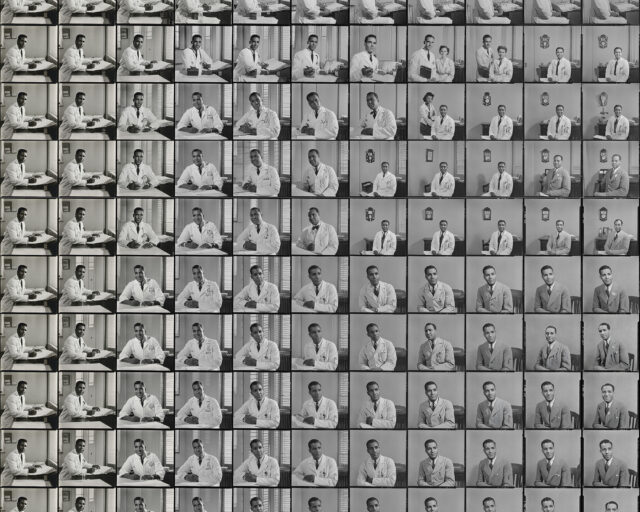

Cropped, blown up, refocused, and uncaptioned, these pictures lose their old propagandist veneer, revealing a stranger, more vulnerable America. A man and woman roller skating in shadow are brought to light. Young boys at a Halloween party are cropped and centered as a man with demon eyes gazes from beyond. A dead eagle, the right wing clipped from the frame, hangs totem-like against a razor-wire fence. A field of burning wheat stubble is magnified into a firestorm.

Muñoz Santini and Panchoaga—who met in 2019 after being invited by the Centro de Fotografía de Montevideo to lead an editing workshop at EN CMYK—characterize their work as “excavations,” which is apt, given how deeply they have mined the New York Public Library’s archive of forty thousand FSA photographs. That the book includes 124 images is a reminder that national histories are always incomplete. Looking through the library’s archive, the editors would have encountered few if any images of the protests, riots, and strikes that convulsed 1930s America, when New Deal programs sought to stave off socialist revolution and resurrect capitalism following the 1929 crash.

Omen belongs to a growing canon of creative work reinterpreting the FSA’s archive. For Killed: Rejected Images of the Farm Security Administration (2010), William E. Jones assembled a selection of 157 negatives destroyed by Stryker—whose editing process involved punching holes in faces, bodies, buildings, and landscapes—and hypothesized about what motivated the bureaucrat’s choices. Day Sleeper (2020), a book by Sam Contis, distills the iconic work of Dorothea Lange to a dreamlike narrative about the waking world, her portraits of people asleep in public balanced by many previously unpublished images by her, both professional and private. Earlier this year, the exhibition Color Photographs from the New Deal (1939–1943), was presented at Carriage Trade, New York. Its shockingly vivid, rarely reproduced Kodachrome images presented pioneering artistic achievements of the FSA photographers in a new light.

Photographs from the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs of the New York Public Library

In a coda to Omen, American novelist, poet, and critic Lucy Ives stresses how tenuous the connections are between fact and fiction when looking at documentary photographs; how our eyes can deceive us. In her view, Muñoz Santini and Panchoaga have created “something powerfully nonnarrative” with their image selections. “What I mean is that Muñoz Santini and Panchoaga make the photographs more difficult to see—and therefore more visible—because in Omen these famous photographs are no longer the photographs that we remember,” Ives writes. “They are not photographs that were taken in 1936 or in 1941. Instead, they were, in a manner of speaking, taken last week.”

Unmoored from time, the images are presented in a way that confounds their original purpose to “introduce Americans to America.” The photographs map a country of strangers and ghosts, while holding a mirror up to ourselves, daring us to open our eyes.

Omen: Phantasmagoria at the Farm Security Administration Archive, 1935–1944 was published by RM and Gato Negro Ediciones in 2024.