A Miraculous Trove of Pre-Stonewall Secrets

In the 1960s, Casa Susanna empowered a community of self-identified cross-dressers at a time when gender nonconformity was a crime.

Andrea Susan, Susanna by the Casa Susanna sign, Hunter, NY, 1964–1968

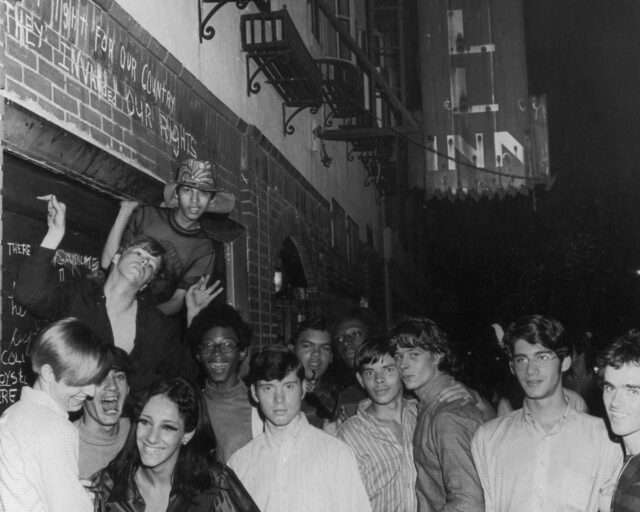

In a photograph from the mid-1960s, identified as a “photo shoot with Lili, Wilma, and friends, Casa Susanna, Hunter, NY,” three women spill out from what appears to be the wooden slats of a closet door. The walls are clad in period-perfect knotty-wood paneling. The women, too, look fabulously of the moment, all kicky little mod dresses and gently curling bobs and headbands and horn-rimmed glasses and pearls. A fourth woman reclines, and yet another stands, filling the tiny room. All are holding cameras pointed at one another. In the corner, a blond with a wicked gleam in her eye trains her pocket-size camera on the person taking the picture. But she’s also winking at her future viewer, whom, one might imagine, every person in this photograph assumed would be someone like them: someone the world saw as a man but who found pleasure in seeing themselves as a woman. Which makes this photo not only joyous but dangerous. Because in appearing as women, each of them, in that moment, was committing a crime. And having the time of their life.

The exhibition Casa Susanna at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, organized in collaboration with the Art Gallery of Ontario and Les Rencontres d’Arles, showcases this image alongside some 160 other works made by and for a community of cross-dressers in New York and beyond throughout the 1960s. (While many of these folks identified as “transvestites,” the exhibition’s curators use the term cross-dressers, and this text follows suit. All identifying pronouns are used per the curators’ direction.) This community had a series of hubs. The first was a wig shop on Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue, run by Marie Tornell. One day in the mid-1950s, Humberto (Tito) Arriagada, who had moved to New York after serving in the United States’ Foreign Information Service during World War II, walked into the shop. It was love at first sight between Arriagada and Tornell—and love at second sight when Tornell met Susanna Valenti, the person Tito had been cross-dressing as since teenage years. The pair transformed Tornell’s shop into a dear, clandestine resource for cross-dressers at a time when New York’s so-called masquerade laws still criminalized wearing clothes associated with the “opposite” gender.

Once this close-knit underground community had the looks, it needed somewhere to show them off. Tornell and Arriagada—now free to be Susanna Valenti more regularly—made their apartment a safe space. In a photograph of “Susanna standing by the mirror in her New York City apartment” (1960–63), the home is a charming hall of mirrors. At the forefront, Valenti poses seductively in a lavender-pink dress not far from the shade of the painted walls, her eyes burning with confidence through the chromogenic print. Behind her, her reflection shows off the elegant cut of her lavender dress; farther back still, another woman stands in front of another mirror, bent over some distant domestic task as a lamp gently illuminates the back of her neck. That lamp, too, is reflected, forming a pair that frames the woman’s dark hair. These photographs are charged. They are proof that their subjects could live as they wanted, happily. They electrify the viewer. They urge the viewer to take charge of their own lives.

The exhibition design groups photographs of women engaged in similar pursuits—posing in front of televisions, for example, or for Christmas cards complete with girly, curliecue well-wishes in ink. The subjects assert their identities through action. They are women because they look and act like women. Femininity is an achievement, and these photographs advertise the spoils. In these images, “wish I was her” becomes “wish you were here.”

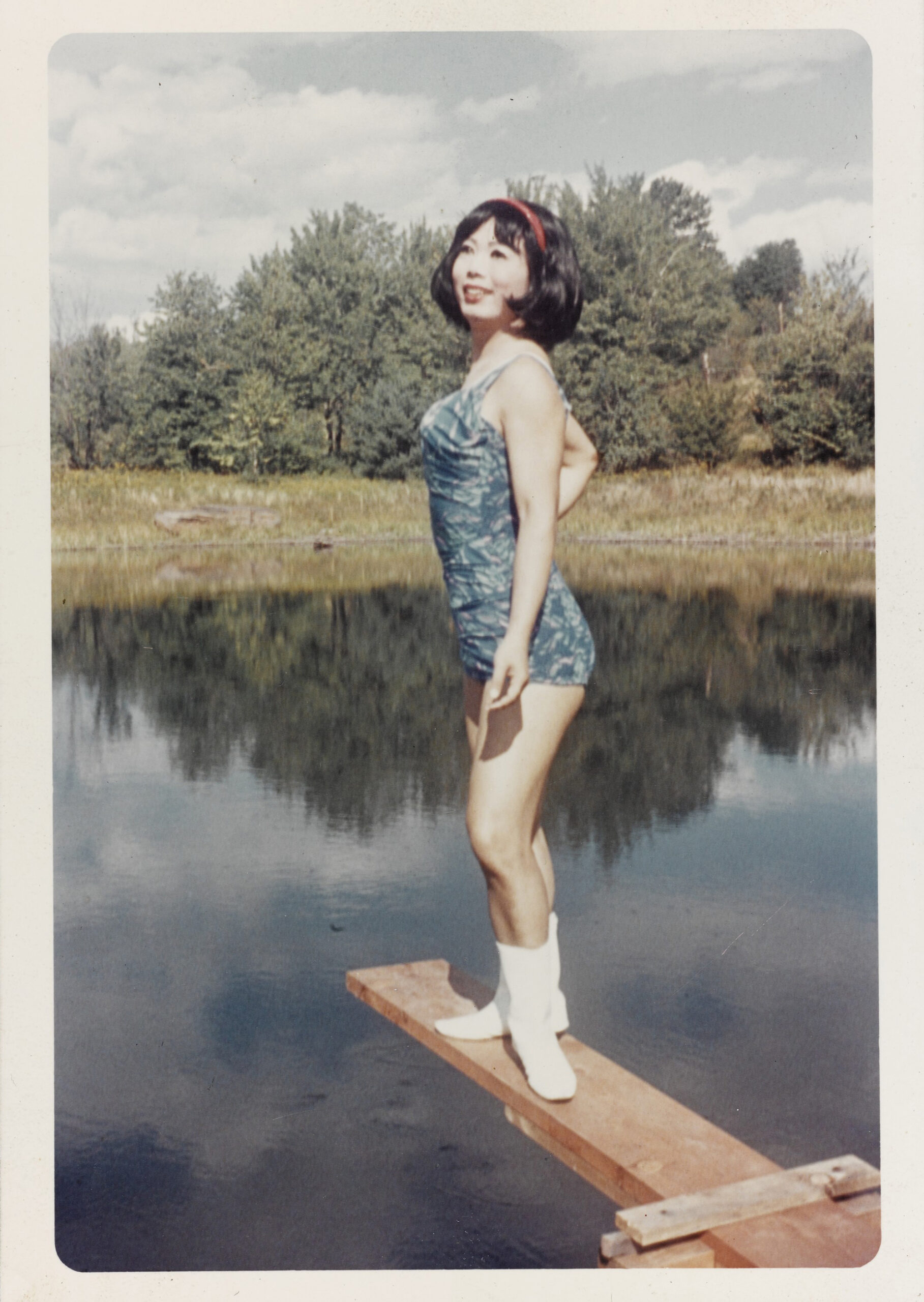

Arriagada and Tornell certainly took charge of their own lives. In 1960, they began transforming a humble cluster of bungalows and a barn in the Catskill Mountains into Chevalier d’Éon—named for the eighteenth-century cross-dressing French spy Chevalière d’Éon—and invited their community to visit and stay. A photograph of “Susanna and Felicity in the kitchen, Chevalier d’Éon, Hunter, NY” (1960–63) shows two women thrilled to be in their element, the former camping it up with her leg on a stool while the latter, cross-legged, laughs and cuts her food as if at dinner theater. Like “Lili on the diving board, Casa Susanna, Hunter, NY” (1966), taken at the second resort Arriagada and Tornell set up in 1964, these are holiday snapshots. They’re proto-selfies. But they’re also performances: moments of people willing themselves into the kind of person and life they desire.

All photographs © AGO

Casa Susanna surrounds these photographs with others taken in their friend Gail’s Greenwich Village apartment, along with copies of the groundbreaking Transvestia magazine, founded in 1960 by Virginia Prince to connect and celebrate cross-dressers across the country. Arriagada starred as Susanna herself for its December 1961 cover. The ephemera, alongside the photographs, help shape our contemporary understanding of transgender identity. Some of these individuals later took further steps towards living as women—medically and legally. Whether or not all the people in these images fit our current categories, the community they built offered the chance to experiment and escape the narrow confines of gender before the modern gay rights movement exploded.

Moreover, the exhibition emphasizes how Transvestia and its photographers seized the means of production: Before the DIY freedom of the Polaroid arrived, they must have had to find sympathetic photo-lab workers to develop their chromogenic and gelatin-silver prints. They certainly kept these photographs safe. Although countless images have been lost, much of this show draws from a cache discovered at a Manhattan flea market in 2004. The pictures are in such exemplary condition that there’s no doubt they were held dear, and perhaps close to the vest. This exhibition is proof not only that people have always refused the despicable gender laws now resurfacing in this country, but also that remaking the world in your own image is possible, vital, and a hell of a lot of fun.

Casa Susanna is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, through January 25, 2026.