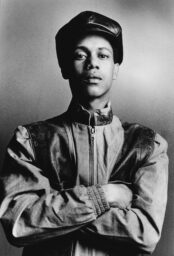

Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo, Ngiz’khumbuza ityma, 2022

On June 26, 2022 twenty-one high-school children below the legal drinking age of eighteen died in a tavern in East London, South Africa, after inhaling methanol fumes in the overcrowded, unventilated venue. In a Soweto shebeen two weeks later, fifteen patrons were gunned down with rifles and pistols in what survivors called “an orchestrated hit.” The actual targets had already left. Follow-up reports of other murders dominated the current affairs programming through much of July until the media frenzy cooled off.

As I mulled over these grisly stories, I thought of the photographer Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo’s work constantly. Last April, the Goethe-Institut in Johannesburg presented a solo exhibition by Hlatshwayo, Umnyakazo, which incorporated works from his compelling tavern-based series Slaghuis I and II. Hlatshwayo, the child of shebeen owners in the township of Lawley, southwest of Johannesburg, doesn’t deny the social impact of the business that fed him. Instead, he seeks catharsis from his inextricable links to it. (Under apartheid, shebeens referred to illegal taverns, as Blacks could not drink or purchase alcohol without restriction.) As a result, there is space and quietude to the images as they explore his invisibility within the shebeen’s confines.

In 2016, Hlatshwayo joined the East Rand–based Of Soul and Joy project thanks to a tip from his mentor Jabulani Dhlamini, a photographer and project manager of the initiative, which seeks to expose vulnerable youth from Thokoza to photography and art through mentorship. (Alumni include the Magnum photographer Lindokuhle Sobekwa.) Through the program, Hlatshwayo was inspired by his contemporary Tshepiso Mazibuko’s use of expired film. The effect was that of “a lot of dirt on the surface,” a kind of spotted, off-color grain. “There was an interruption,” he told me, from his bare home studio in Lawley. “It was not a clean image and I really liked that.”

Hlatshwayo found a permissive environment at Of Soul and Joy and access to photographers who gave interesting workshops. “What I liked about Jabu was that when he didn’t understand the space you were entering, he’d call on someone who could understand it better to give you more feedback,” says Hlatshwayo, referring to Dhlamini. “Some people try to recreate themselves through their students.” Two years later, Hlatshwayo embarked on the series Slaghuis (an Afrikaans word meaning slaughterhouse or butchery) as a way of voicing the violence of his surroundings. In a reflective article he penned for the Mail & Guardian, he describes, at the age of seven, waking up to a dead body and feeling “overwhelmed by the desire to disappear.”

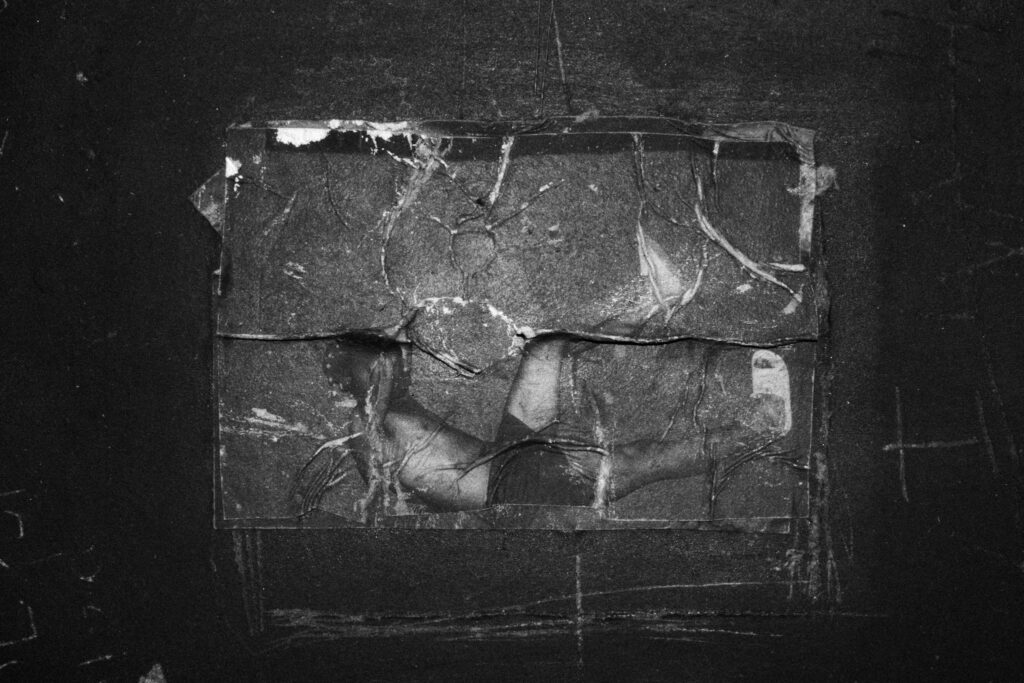

In Slaghuis I (2018), Hlatshwayo reenacts this desire, layering his images through multiple phases of photography until the subject (often himself) appears distressed, distorted, or dismembered. To add further textures, Hlatshwayo reintroduces prints of the initial photographs into the tavern space, allowing patrons to step on or ash their cigarettes on them, and then rephotographs the paper. In this initial series, Hlatshwayo’s impulse to experiment comes across as feverish and fearless, but also a bit literal.

By the time he has a second go at the topic—Slaghuis II (2019) was first exhibited at the Market Photo Workshop in February 2020—an embodiedness begins to permeate his approach. This time, Hlatshwayo exhibits a flair for the Ballenesque; with less situational context in favor of more conceptual execution. These stylistic changes have been gradual, but the photographer’s openness to collaboration and keenness to explore multiple disciplines has meant that breakthroughs are always around the corner.

As soon as Slaghuis II opened in February 2020, the exhibition had to move online because of COVID-19 lockdown restrictions. Fatigued, Hlatshwayo retreated and thought about how to create new work. “I was wondering about walls and imposing movement on walls,” he says of a process-driven style through which he began to regard installation as performance. When the photographer and curator Luvuyo Equiano Nyawose was selected to be part of the Goethe-Institut’s Young Curators Incubator 2022 program (in partnership with the History of Art department in the Wits School of the Arts), he opted to collaborate with Hlatshwayo, after they had each exhibited work at the South African Pavilion at the Dubai Expo in 2021.

The resulting exhibition repurposes some of the images contained in Slaghuis I and II and explores interiority through tactility while experimenting with various modes of presentation. “You saw newsprint, you saw wallpaper, you saw video and engraving, which are all super related to his image-making process,” says Nyawose.

Nyawose, who describes their collaboration as “collapsing the line between curator and artist” nudges Hlatshwayo towards the idea of inconclusiveness, where the production process—and the subversion of it—becomes a language in and of itself. The Umnyakazo exhibition became both “format and medium in real time,” says Nyawose, crammed with affective details such as the use of specialist paint that would change hue according to the time of day. He spent time thinking about “the idea of shadows,” which is prominent in Hlatshwayo’s work.

While the shebeen was a site of momentary pleasure and an appendage of the migrant labor system for predecessors like Rose Motau and Santu Mofokeng, for Hlatshwayo the speakeasy of today lays bare the limits of self-determination. What Umnyakazo achieves through a lack of finish, a speculative approach, and a preference for less stable materials, is a sharp dissection of alienation. As we are decreasingly able to physically access the tavern in his newer work, a suggestion that the photographer is no longer preoccupied with his pain as an individual, Hlatshwayo edges towards more systemic concerns. Through the use of scrawls and screens, he ponders the unaltered spatial landscape of apartheid (suggested here by materials that evoke the posterized city), and the overarching violence that still corrals the underclasses to the beer hall.

All photographs courtesy the artist

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.