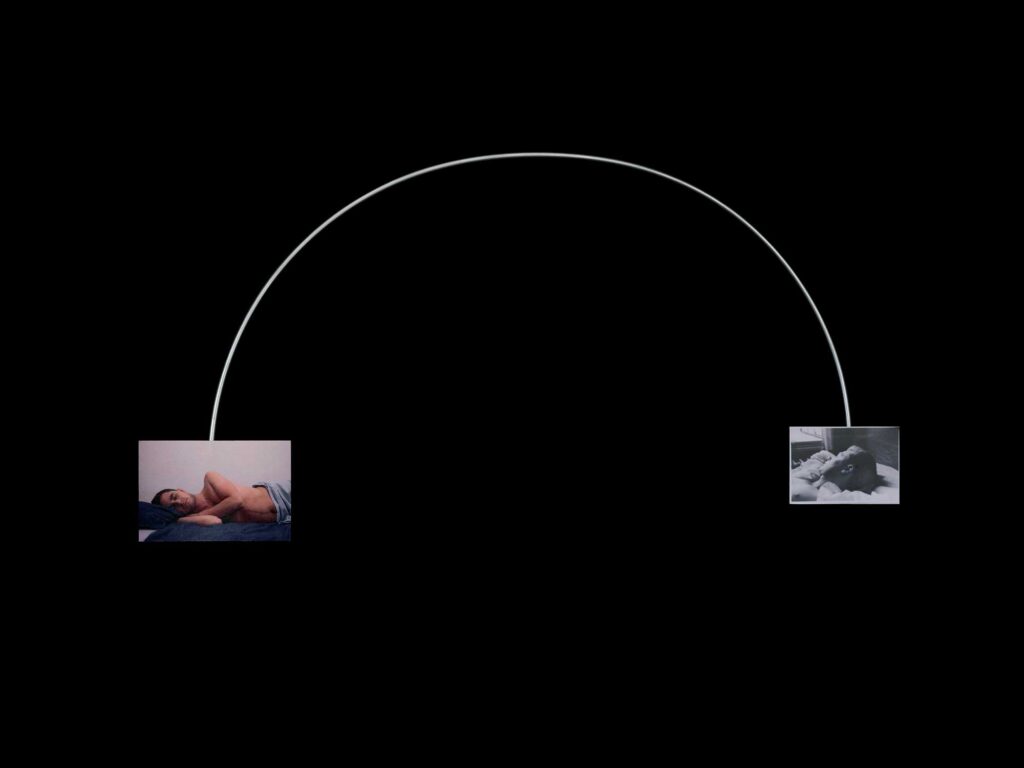

Gonzalo Reyes Rodriguez, Untitled (Piso de Isaac), 2021

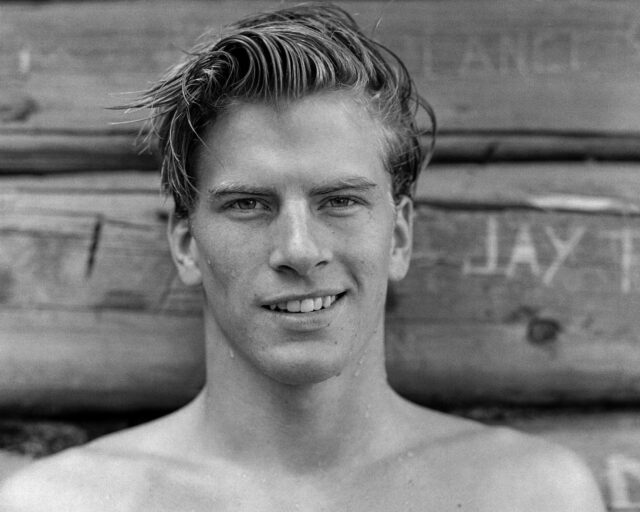

Gonzalo Reyes Rodriguez was in a used bookstore in Mexico City in December 2020 when a packet of vintage snapshots caught his eye. Most were self-portraits of a young man with luscious teen-idol locks, a supple pout, and the vulpine gaze of someone who can pose as well as compose. There were over two hundred pictures, including those with or of friends and lovers, all perceptibly queer, dressed up, playing dress-up, or in various states of undress. Handwritten on the backs of the photos were dates between 1987 and 1993, as well as the signature “Technoir.” Perhaps taken from the nightclub scene in The Terminator and that genre of dystopian thrillers, the pseudonym casts a pallid haze over otherwise effervescent vignettes. These blithe visions of youth appear in stark contrast to the reality of the time—the convergence of the AIDS epidemic and Mexican peso crisis. Rodriguez, curious and moved, procured the pictures for his studio.

Appropriating found ephemera is central to Rodriguez’s artistic practice. He was born and raised in Mexico, and his family moved to Chicago when he was thirteen. Before he was even conscious of art and the possibility of it as a career, he was obsessed with images. He cut out photos of Latin pop stars from his sister’s Eres magazines and plates from encyclopedias that his father purchased secondhand. “It was how I learned about the world,” Rodriguez says. “I knew I was gay, and it was my way of figuring out who I was because I constantly felt alienated.” Rodriguez eventually applied and was accepted into Chicago’s After School Matters program, which provides teens a stipend while they learn a trade skill of their choice. For Rodriguez, it had to be photography.

As Rodriguez went on to study art—he received his BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and MFA from the University of Pennsylvania—he became intrigued by the slippage of time and mutability of a photograph’s meaning . “When I started grad school, I didn’t really want to make photos anymore,” Rodriguez says. “I was less interested in making pictures than understanding how they function.” He discovered the works of artists like Nancy Davenport and texts by the theorist Ariella Azoulay, who writes about photography as a tool for social and political interrogation. For a self-titled show with Roots & Culture Contemporary Art Center, Chicago, in 2018, Rodriguez juxtaposed archival photographs from the Nicaraguan Revolution with production notes and stills from the Nick Nolte film Under Fire, text from a 1983 Playboy interview with the Sandinistas, and excerpts from declassified psychological-operations manuals. Emblematic of his more documentarian mode of working, the exhibition unraveled tidy, valorizing narratives about the United States’ intervention in Latin America.

The Technoir archive inspired Rodriguez’s return to a more intimate way of engaging with pictures. “They’re private but can be read publicly,” he says. “They move through the personal and political in interesting ways.” What if, he wondered, their potential energy was intentionally harnessed to construct a shared history? His cheekily titled New Photographs series marks the first time he incorporated the Technoir archive in his work. He considered the found photograph an object of inquiry and elevated status, influenced by the Pictures Generation, particularly Sarah Charlesworth’s Objects of Desire (1983–89), in which she rephotographed iconic imagery sourced from antiquity to contemporary culture against saturated backdrops of pure color—semiotic gestures that sought to evoke and stimulate the cognitive process of desire. For New Photographs, Rodriguez superimposed Technoir’s images over his own, staging heart-to-hearts across time.

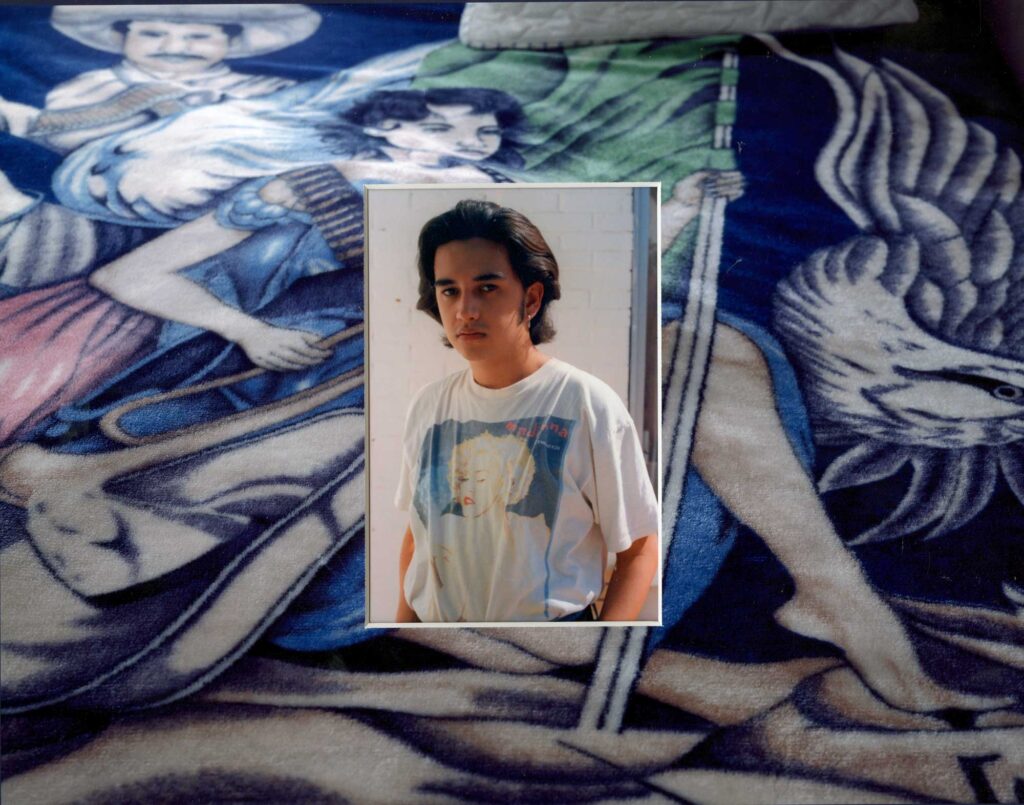

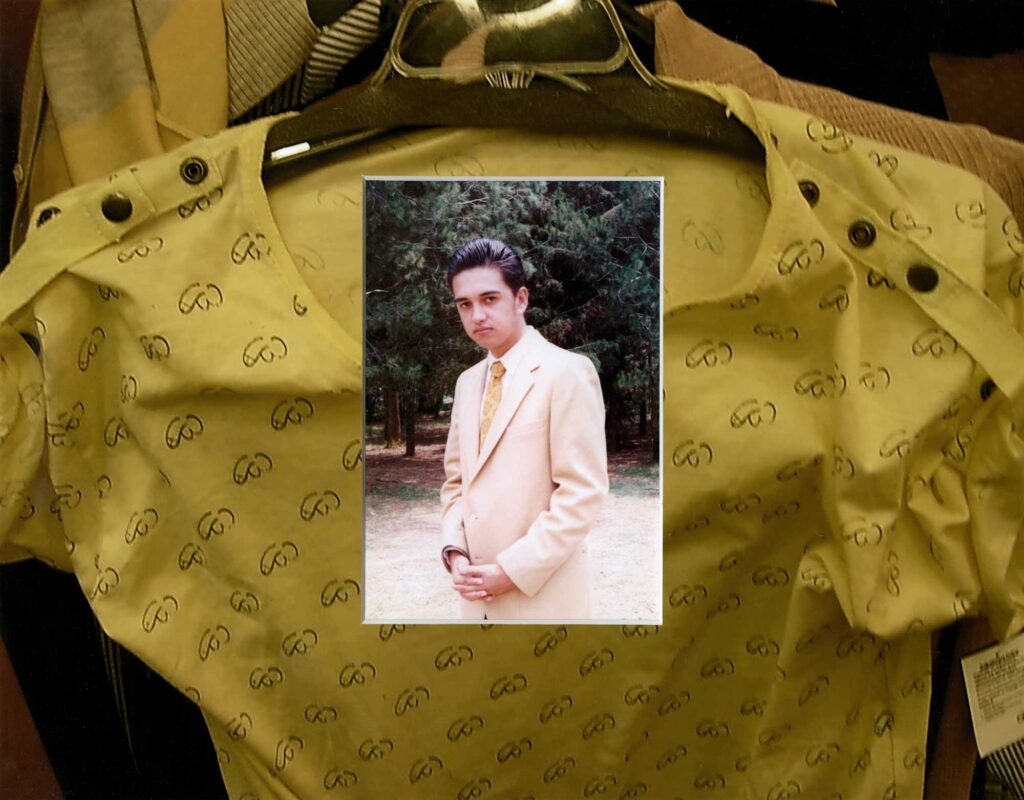

The tension between middle-class conformity and ecstatic self-liberation ripples on the surfaces of the works in New Photographs. In Untitled (Formal Portrait) (2022), a vibrant yellow blouse patterned with the childish scribble of a penis and balls looms behind Technoir in a tan suit. In Untitled (Dying Slave) (2021), the sterile, classical depiction of agony is disrupted by a gonzo shot of Technoir in a shower stall, donning a red silk bathrobe, with shoulder-length hair and a put-on expression of unrequited love. In Untitled (Madonna) (2021), an image of Technoir wearing a faded Madonna T-shirt overlays a photograph of a rumpled blanket printed with the portrait of a female Mexican revolutionary, creating a fun-house mirror of gendered power play. Clearly, for Rodriguez, the entanglements go beyond the intellectual and art historical. “Why did this person decide to make this photo?” he asks. “Why have I wanted to make the same photo in the past? There’s something there like desire, the unpacking of something.”

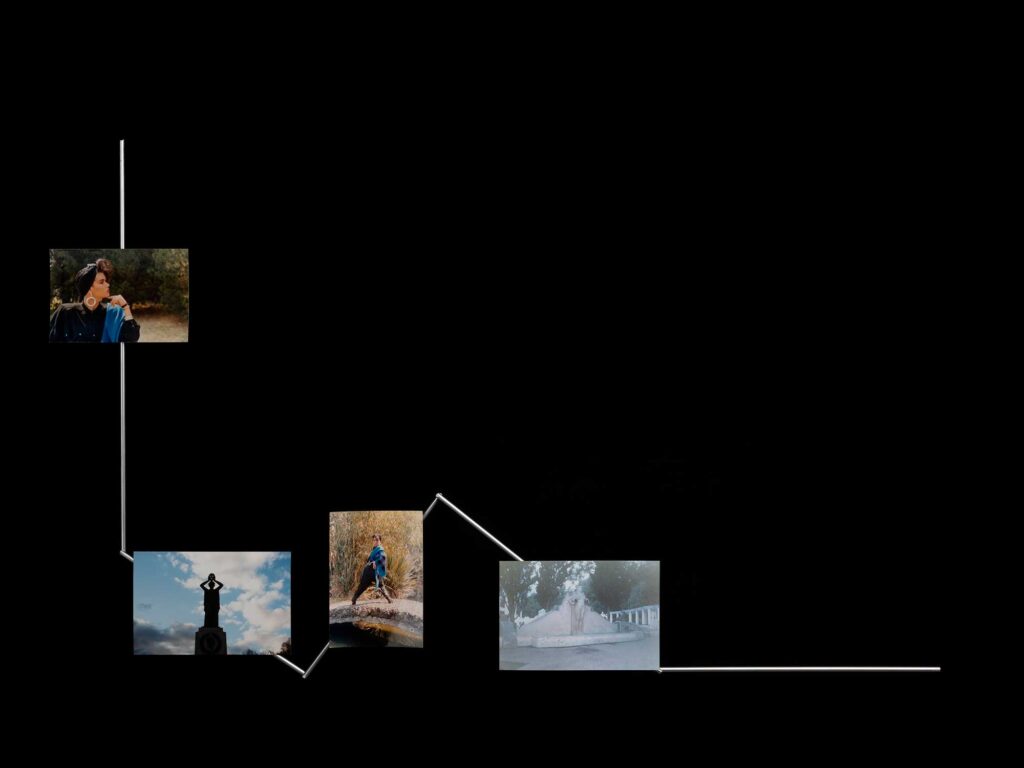

For his most recent show Survey, at David Peter Francis gallery in New York, Rodriguez diversified the milieu of images while dialing up negative space and what Charlesworth describes as “the coherence of photographic illusion,” expanding his visual dialogue with Technoir. He photographed what appear to be steel mobiles (some resembling Tom Burr’s abstract but sensual Addict-Love tableaux) on which hang photographs from art history, retro men’s magazines, the Technoir archive, and Rodriguez’s own portfolio and iPhone camera roll. These are not digital collages, Rodriguez clarifies, but installations he had photographed in the studio then dismantled, never to be exhibited in physical form. He cites as a reference the German art historian Aby Warburg and his Bilderatlas Mnemosyne, a collection of black burlap boards pinned with clusters of images that share motifs across geography and time. Warburg calls this spatiotemporal distance and one’s consciousness of it “Denkraum”—a room for reflection—and that is exactly what Rodriguez provides, more than he ever had before, in Survey.

The historical and biographical details add dimension to the constellations of images in the framed night skies that compose most of Survey, but the works resonate in their spareness. In Figure II (2024), two photographs depict a young woman in an ’80s power suit: imperious shoulder pads, ostentatious jewelry, and wild hair barely contained in a tight headwrap. In her mind, she is Linda Evangelista. “Is she a friend of Technoir’s? Is it Technoir in drag?” Rodriguez asks. The other two photographs in the frameare Rodriguez’s own. One is of a silhouetted monument to the Spanish dramatist Jacinto Benevente, of an actress lowering a Grecian mask onto her face. Another is of the Fuente de los Cántaros, a fountain in Mexico City that depicts the figure of an Indigenous woman holding pitchers from which water momentarily flows. She is modeled after Luz Jiménez, a Nahua woman whom scholars consider the face of twentieth-century Mexican art because she was the constant muse turned collaborator of artists like Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco. The Fuente is in Parque México, close to where Rodriguez’s parents currently live, and where he believes Technoir staged one of his guerrilla fashion shoots. The photographers, past and present, are captivated by moments of becoming and understand exactly how pictures are not only representational but are themselves conduits of power.

All photographs courtesy the artist and David Peter Francis, New York

Rodriguez’s spiritual collaboration with the Technoir archive recalls Jonathas de Andrade’s Tropical Hangover (2009), an installation of found photography and writing guided by entries from a stranger’s diary which the Brazilian artist salvaged from the trash in Recife. The result is a collective reconstruction of a city crumbling in the wake of colonialism and rapid modernization, and the human drama that persists. Like those of de Andrade, Rodriguez’s works are constructs of empathy, divining meaningful and humane coincidences across time. To this day, Technoir’s identity remains a mystery to Rodriguez. He doesn’t know whether the young man died of AIDS-related illness or grew into normative obscurity. But in the great void of what is not known, there’s the possibility of redemption through remembrance and beauty. In the triptych Sleeping Boys (2024), Rodriguez uses the same arc structure to visually connect duos of young men in repose: Rodriguez’s friend, Technoir’s lover, some male models, The Sleeping Hermaphroditus. The arc suggests a projectile, perhaps a flare, a parabolic return, a threshold, the path of droplets in the atmosphere waiting to refract light into a rainbow, or an arm wrapped around you, drawing you into an embrace.

Read more from our series “Introducing,” which highlights exciting new voices in photography.