A Shimmering Portrait of Contemporary Iran

When Sara Abbaspour returned to Iran after working in the United States, she found a new way of photographing her home country.

Sara Abbaspour, Untitled (girls and the horse sculpture), 2024

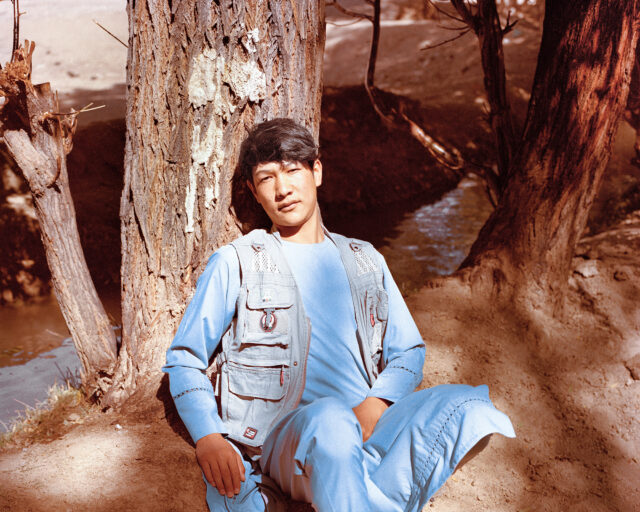

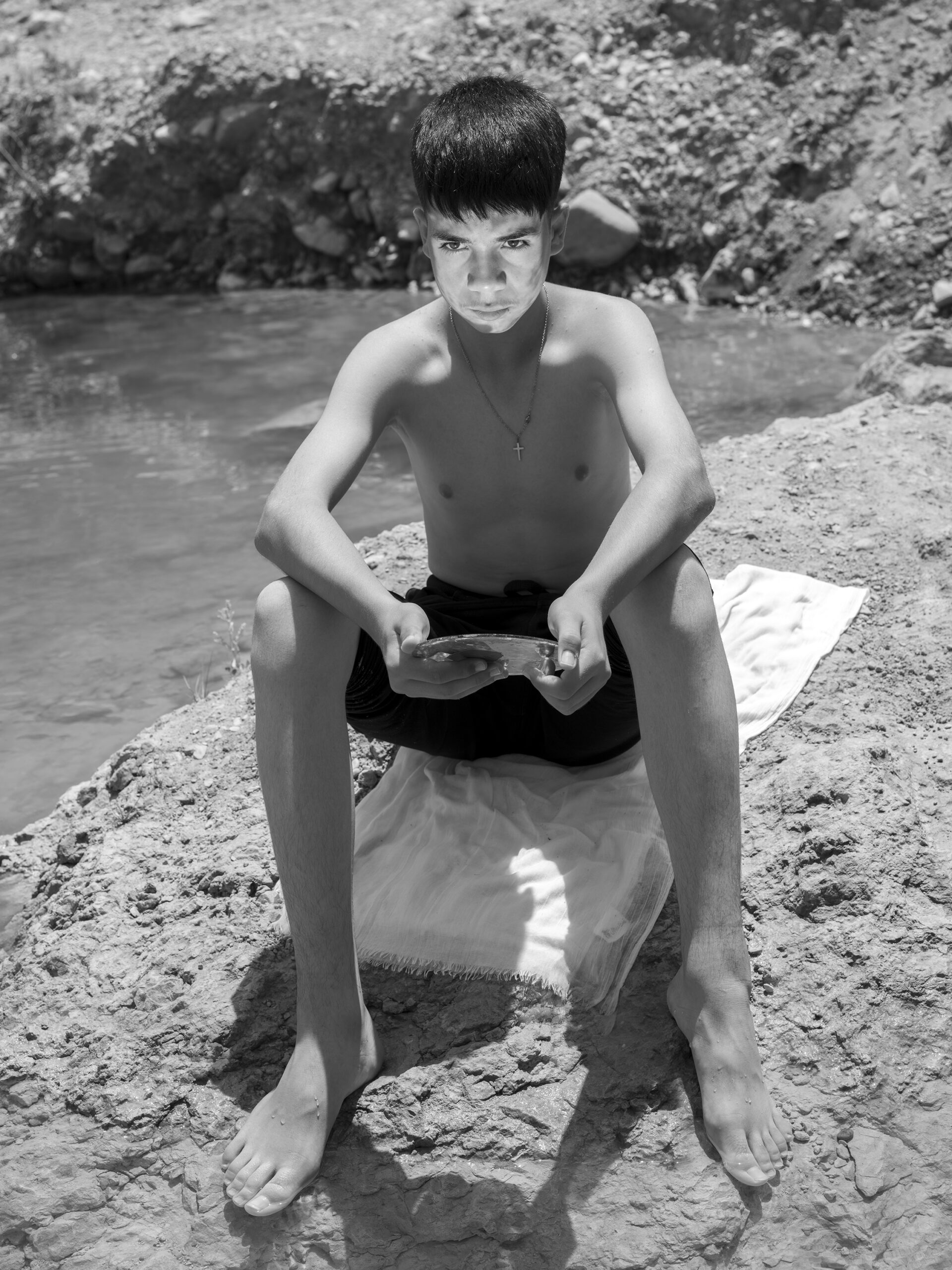

Everything seems quiet and calm in Sara Abbaspour’s series Floating Ocean, yet quiet and calm are not words immediately associated with the image of Iran, where the photographs were made between 2019 and 2024. The absence of the usual clichés was a deliberate choice by Abbaspour, who imbued the geography of her country of birth with the aesthetics of the place where she discovered portrait photography as a way to tell her stories.

Abbaspour first experienced photography as a tool in her undergraduate program in urban planning and design in the city of Mashhad, in the northeast of Iran. It turned out she enjoyed photographing the city more than trying to plan it, and so she changed course. Her first photography degree at University of Tehran was theory heavy; seeking a practice-based education, she enrolled at the Yale School of Art in 2017.

In her first series, White (2015–16), Abbaspour’s training as an urban planner collides with practical constraints—it is illegal to take photographs in public spaces in Iran. In these images, she captured the remains of houses destroyed in the name of renewal in the pilgrimage city of Mashad. Unseen interior walls, once the site of private lives, become external walls, exposed to the city’s traffic. The municipality’s whitewash inadvertently turns the unsightly into the monumental. “I didn’t make portraits when I was in Iran. I thought I could work with the urban fabric metaphorically to talk about the ideas that I had,” Abbaspour says. The liminal state of these walls, pulled down but never rebuilt, provided her with the kind of poetics that many Iranian artists find useful in a country where direct statements can easily cause trouble with the authorities.

Abbaspour’s move to the US pushed her in a new direction and a new way of looking. “I was lost when I got to the US. I didn’t have any connection to the place. My English wasn’t very good at the time, so I made myself go out every day to photograph people. I started to enjoy the process of meeting and collaborating with them.” Through portraiture, she connected to her new country, and that newfound territory in turn changed the way she photographed Iran when she returned after almost six years.

She began Floating Ocean on her first visit back to Iran, but issues around her US visa stopped her from visiting again to finish the project until the summer of 2024. By this time, she had found a route away from the safety of the metaphor and was settled into the American tradition of portraiture. Influenced by the work of Judith Joy Ross, Mark Steinmetz, and Dawoud Bey, she blended her newfound confidence in photographing people up close with her idea to evade a specific geography. There is poetry here, but no conundrums. Her frames are occupied by individuals at ease with themselves in front of her camera.

The name of the series points to the vastness of Iran and how it and she have both changed so radically since she departed for the US. For returning expats these days, the most eye-catching change is the number of women who defy the compulsory Hijab rules, eradicating one of the easy visual markers of the country. In 2020, Iranians protested the Hijab rules after a young woman, Mahsa Jina Amini, was killed in the custody of the moral police who enforce them. Many young people were killed and maimed, and women still face punitive measures for refusal to comply.

Throughout the series, Abbaspour photographed her subjects without the mandatory cover. Without that signifier, the background is the only way to pin the geography. The subjects don’t give away many clues. The girls holding each other or the boys wrestling could be somewhere in the American Midwest. The woman washing her face with a hose could be in South America. Even where some material elements may point to the geography, it is very unspecific, the rooftop in Mashad where a young woman is leaning over the parapet could be any Middle Eastern country. Abbaspour directs our attention to the person in the frame and not their environment. To that end, she deliberately avoids color as she feels it provides too much documentary information.

Abbaspour’s use of black-and-white photography creates a sense of timeless, placeless landscape. As does her framing. Robert Capa’s famous assertion that if your photographs are not good enough, you are not close enough, takes new life in Abbaspour’s method of photographing Iran, where she proves that if you zoom in hard enough, you will discover the universal.

Courtesy the artist

Sara Abbaspour is a shortlisted artist for the 2025 Aperture Portfolio Prize, an annual international competition to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition.