After a Revolution, a Chilean Photographer Mourns the Martyrs

In a new series about Chile’s political uprising, Javier Álvarez crafts a striking account of family grief and revolutionary joy.

One afternoon a few months ago, an old couple drank a cup of coffee at a dinner table while the setting sun entered through a small window, highlighting their wrinkles. Their eyes, looking down, express more exhaustion than relaxation. Behind the man is a portrait of the couple’s daughter, a beaming woman dressed all in white and sitting on green grass. Her name was Paula Lorca. She was in her mid-forties when her body was found burned in a supermarket on the periphery of Santiago de Chile on the night of October 19, 2019. The market had been looted that night after a series of events her parents are still trying to make sense of. They do not know who was responsible for her death. “What I want most is justice,” her father, Ramón, told the photographer Javier Álvarez. “We are poor, and we might not get it, and that’s what angers me the most.”

Álvarez, born and raised in Chile, and currently based in New York, took a photograph of the couple at their dinner table last fall, after reaching out to the families of men and women killed during the historic nationwide protests that started in October 2019 and continued for months. (According to Chile’s National Institute for Human Rights, law-enforcement officers injured more than four hundred protesters—leaving many partly or completely blind—and more than thirty people died during the unrest.) Álvarez’s research turned into a striking new series, Paisaje Invisible (Invisible Landscape) (2020)—a close-up of the empty corner where a man was shot months before, or the ashes of the supermarket where Paula Lorca’s body was burned. “I wanted to focus on the invisible,” Álvarez says. “On what is left that nobody thinks about.”

Álvarez asked the families what he should photograph, or which anecdotes needed foregrounding. “I was looking for a way to expand the limits of documenting,” he explains. “The families chose through which door I could enter [their memories] or leave them, and I had no idea where they would take me.” One man wanted to show him the old soccer shoes he once got for his little brother, who was killed. A father displayed the tattoo he got on his left arm in memory of his son. Most of the people he met, Álvarez says, came from working-class families struggling to make ends meet.

At the time of Paula Lorca’s death, a few months before the global COVID-19 pandemic exposed unconscionable economic disparities in much of the world, Chileans were already engaged in an urgent conversation about inequality. In response to the government raising metro fares, and callously advising students and the working public to wake up earlier to avoid the peak-hour prices, a group of high-school students sparked el estallido social (the social explosion). Civil unrest against the unpopular right-wing government spread far and wide across the country, in protest of not only the subway hike, but also the broader politics of austerity that left more than half the country’s wealth in the hands of the richest 5 percent. Demonstrators set fire to subway stations, toppled statues, and clashed with the police. Chileans united under a single cry, demanding reforms to the private education and pension systems, and an end to the authoritarian constitution that General Augusto Pinochet had put in place in the early eighties. The protesters also renamed Santiago’s main square, Plaza Italia, where they stood vigil day and night for months. They called it “Dignity’s Plaza.”

A protest or revolution is a golden visual performance: the crowds, the homemade signs, the graffiti. But Álvarez photographs the grief that undergirds the protests. A man by the main statue at Dignity’s Plaza, dressed in all black, waves a flag with the printed photo of his late brother Cristián Valdebenito. “He was a martyr of the people, a martyr of the primera línea,”he told Álvarez, referring to the frontline protesters who risked tear gas or rubber bullets to defend the right to dissent. Valdebenito, a forty-eight-year-old jack-of-all-trades, was killed in confrontation with the police in early March. “When el estallido social began he was, sort of, born again,” Valdebenito’s sister reflected. “He would go to work and, on Fridays, the only thing he cared about was going to the protests, because he said that by doing that, we could all change what was happening.”

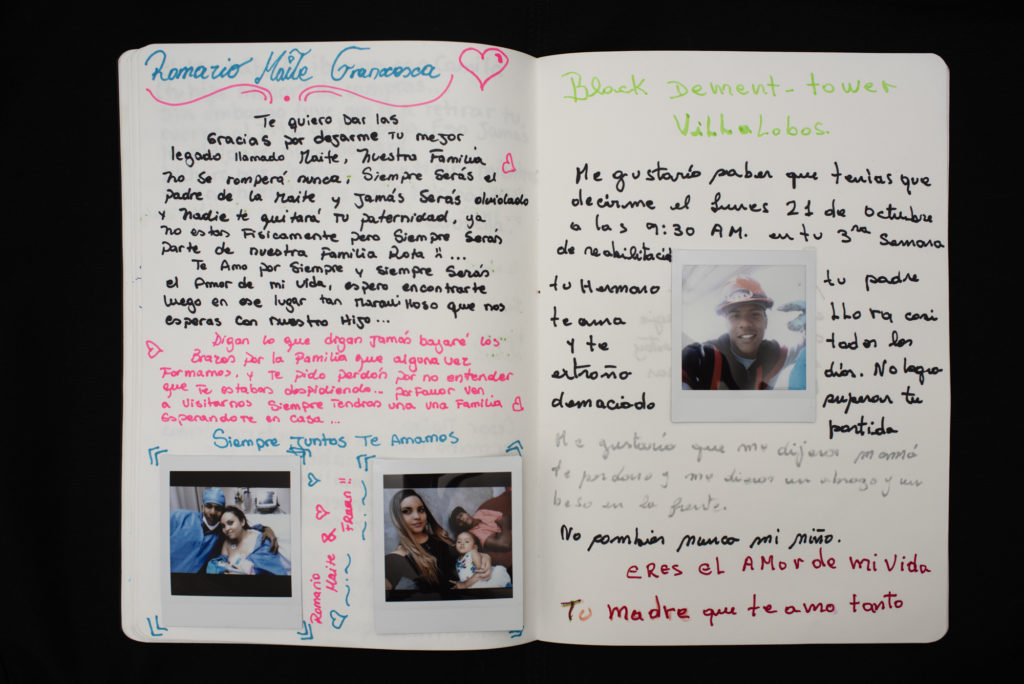

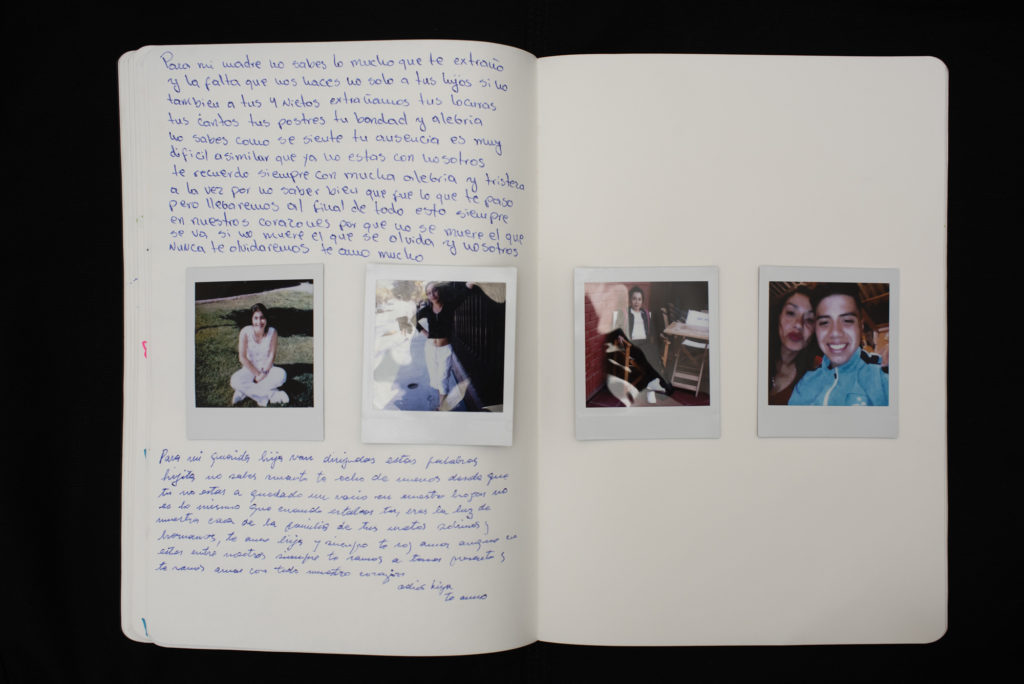

Álvarez is in his early thirties and, during national demonstrations in 2006 and 2012–13, he was a student protestor. No longer a frontline warrior among the students, he approached the families of those who died the way an archivist would. He photographed scrapbooks that relatives had made to say goodbye to loved ones, including Romario Veloz, a twenty-six-year-old Black Ecuadorian who had migrated to Chile as a child. “You will always be a part of our now-broken family,” Veloz’s partner wrote. Veloz was a hip-hop dancer who’d joined a small protest in the town of La Serena on October 20, 2019, that ended abruptly when the military started shooting at protesters, killing Veloz. Two weeks before Veloz’s murder, his daughter Maite had celebrated her fourth birthday.

A year after el estallido social began, the country voted to change the constitution, and a new process began to elect those who will rewrite it. Following months of lockdown because of the pandemic, hundreds of exhilarated protesters gathered on Dignity’s Plaza to celebrate. Álvarez focused his camera on a lone, shirtless man shouting joyfully to an empty avenue, as if Diego Maradona had just scored a goal against England. As with any revolution, there are not only victories, but martyrs too. With Paisaje Invisible, Álvarez manages to capture revolutionary joy, though he mainly sits with the stillness of bittersweet afternoons, when parents drink coffee while remembering the daughters that el estallido social left behind.

All photographs were created using FUJIFILM X-Pro3 Mirrorless Digital Camera.

All photographs from the series Paisaje Invisible (Invisible Landscape), 2020, for Aperture. Courtesy the artist