@Aiww by Jacob King

Images from @Aiww on Instagram

Standing in a long, slow line to buy a ticket for the Ai Weiwei exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, I found myself gazing down at my iPhone, scrolling through Instagram. @Aiww is a prolific Instagram user—as of May 5, he had uploaded 2,551 photographs, and had 63,000 followers—and early that morning, lying in bed, I had browsed through a half-dozen photographs shot at Mr. Ai’s Beijing studio, including one where he was posing with Martha Stewart. The guests at Mr. Ai’s studio—celebrities, curators, artists, students, gallerists, friends—are frequently the subjects of his posts, and they are often photographed sitting around a table in his courtyard. Comments below each image try to disentangle the identities of those pictured: “Who is that?” one person asks, while another answers, “It’s Jens Farschou” (a prominent Danish collector). A comment from @delgrantx on that morning’s Martha Stewart post, however, was more acerbic (perhaps unjustifiably so) and it stuck in my mind: “So strange, is she in China to visit the sweatshops where her crap is made? Then she takes a side trip to someone who is a beacon for the human rights movement.”

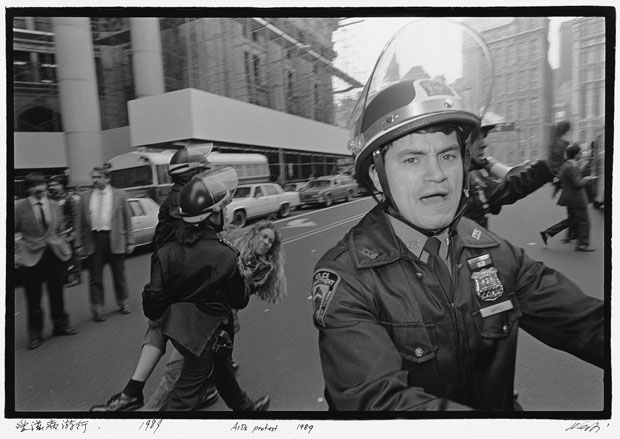

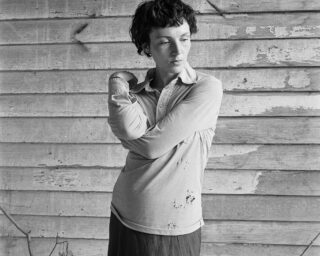

Photography has been an integral part of Mr. Ai’s practice for decades, and the Brooklyn Museum exhibition, Ai Weiwei: According to What?, presents a number of his pre-Instagram photographic activities; chief among them is a group of black-and-white photographs shot by Mr. Ai while he lived in New York between 1983 to 1993. Framed and hung down a long wall, these photographs document Mr. Ai’s life and the lives of his Chinese expatriate friends, at first in Williamsburg and then the East Village. From the point of view of outsiders, they visit Coney Island, pose next to the 8th Street subway sign, watch the St. Patrick’s Day Parade, lie around on beds and sofas, and make many pilgrimages to Allen Ginsberg. But more broadly, they show us the city in the decade before Giuliani: the porn theatres in Times Square, the Tomkins Square Park riots, homeless men living on the streets of the Lower East Side, the Pyramid Club, an ACT UP protest at City Hall, a man in the subway holding up the sign: “I have AIDS. Please help,” and ending with a young Bill Clinton campaigning in midtown. Looking at the Brooklyn Museum, I felt close to these photographs; I live near the bodega in front of which Mr. Ai photographed himself in Williamsburg, I recognize the “Ms. Cohen” type with which he photographed himself in the East Village; Mr. Ai isn’t over there, in some foreign land, he was right here, in New York, where I live. But at the same time, the New York of these photographs feels utterly foreign—a bohemian place that existed where today much of downtown resembles a beautified and policed shopping mall.

Mr. Ai’s photographs on Instagram feel at once farther away—coming at me from across the globe—and yet, much closer—these events are happening right now, and appear in the palm of my hand. Like his New York photographs, but without the identifying captions that tell us who and what we are seeing, they show the goings on of Mr. Ai and his friends: the visitors to his studio, his travels in and around Beijing, the peregrinations of his long-haired cats and his young son (who recently has been making ceramics, and who, just this morning, I see gazing down with fascination at a beetle walking across a glass plate). Some are self-consciously “artistic”: compositions of shadows and hands, of the ivy growing on the courtyard wall of his studio, many shots of flowers, numerous black and white photographs of young Chinese with wild haircuts. We see Mr. Ai himself in many of his New York photographs, and on Instagram Mr. Ai’s self-portraits seem to have reached their zenith: the best of these, like those of his cats, or his son, are highly playful and infused with a sense of wonder; he shows us his hairy flesh and bulging stomach in black and white (evoking John Coplans); in one of my favorite recent shots, we see Mr. Ai from below, the bottom of his face covered by white cloth, his eyes looking out to the left, while a purple twisty drinking straw circles around and approaches his forehead like some fantastically strange machine.

The 229 New York photographs were chosen from over 350 rolls of film (more than ten thousand images) shot by Mr. Ai while he lived in the United States, and they were first printed in 2010, for an exhibition at the Three Shadows Photography Art Center in Beijing. As if to draw out a narrative around a decade in which Mr. Ai seemingly carried a camera with him everywhere—absent, he claims, any intention to exhibit the results—many of these photographs are printed like contact sheets, with three or more small, consecutive images on a single sheet of photographic paper. After they were exhibited, Mr. Ai uploaded them to his Google + account, where anyone with Internet access can view or download them. Also on his Google + page is an astounding album of 249 photographs that document the destruction of Mr. Ai’s Shanghai studio complex by the government in January 2011, as well as a group of photographs of rubble and collapsed buildings—one showing a child’s toy crushed beneath bricks—shot after the Sichuan earthquake in May 2008. But the most recent photographs on Google+ date from June 2012, after which it seems Mr. Ai shifted entirely to Instagram (possibly because of difficulty accessing Google in China, a country where both Facebook and Twitter are also blocked.) In a way this is a shame, as retrospectively, the album-based Google+ viewing is far more rewarding and easier to navigate than Instagram’s continuous, small-screen stream. As I scrolled through Mr. Ai’s Instagram feed after visiting the exhibition at Brooklyn Museum, I started to feel depressed and fatigued; there were simply so many photographs, and very few of the quality or poignancy of his New York pictures. Could I really scroll through 2,500 photographs on my iPhone? (It took me an hour just to make it through the past six weeks of his posts.)

Yet there is admittedly a pronounced difference between scrolling through photographs each morning on Instagram (where Mr. Ai’s posts, because of the time difference, generally dominating my morning feed), and a retrospective scroll through one user’s photo stream. Pushing up again the pastness of photography, Instagram functions in the present tense: a photo says that I am here doing this, with this person, right now. Photographs are not shown with the time and date of when they were posted, but rather, each has a shifting frame oriented around the moment of viewing: it was taken “26 seconds ago,” “43 minutes ago,” “7 hours ago,” “5 days ago,” or “14 weeks ago.” It is precisely the temporality of Instagram which Mr. Ai exploits poignantly: an underlying meaning of all his photographs in and around Beijing is that he is being denied his passport and is prohibited from travelling internationally (this is partially why everyone comes to visit him in Beijing). Mr. Ai’s frequent photographs of rows of uniformed soldiers, surveillance cameras, and police cars broadcast a real-time view of the Chinese security state, and the long-haired cats languorously perched in many of his most beautiful Instagram photographs become stand-ins for the artist, representations of his confinement.

Anyone who declaims the waning or obsolescence of photography’s “indexicality” hasn’t spent much time on Instagram, where much of the appeal—as opposed to Twitter, for instance—is the insistent veracity by which posting an image informs the world about what you have just seen. One of Mr. Ai’s most recent photographs shows a museum wall text with parts of it clearly painted over in white, and a hairdryer visible in the frame, while a follower explains in a comment: “Under the pressure of Shanghai Anituities Authority and polic, Shanghair moden art museum has to remove ai’s work and clean his name from the wall, now u are looking the stuff drying the wall with a blower” [sic]. In another series of photographs showing parts of a poster advertising an exhibition at the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing, the comments section below each image transcribes a phone conversation between Mr. Ai and the museum’s director, in which Mr. Ai conveys his anger at discovering his work in an exhibition in which he was not listed among artists or mentioned in any of the signage and press materials. Following these conversations is a photograph showing Mr. Ai’s work being removed—at his own insistence—from the museum, wheeled out through the front door.

The Brooklyn Museum exhibition includes much more than the framed New York prints. Among the other photographic works on view are a series of color photographs documenting the construction of Beijing’s Olympic stadium that are tiled and hung like wallpaper from floor to ceiling, and, at the end of the show, a bank of twelve flat-screen monitors scrolling through the 7,277 photographs that had previously been uploaded to Mr. Ai’s blog, before it was deleted by the Chinese government. But aside from this installation—a sort of photographic data dump—the curators make no serious attempt to present Mr. Ai’s “social media” activity, or to trace how the changing frames of his photographic production might affect the content of his images. Instead, as if to make up for this gap, the walls are filled with pseudo-participatory rhetoric and the beguiling term “#Activism.” I was unsure what this was supposed to mean: was it an exhortation to be a digital “activist”? To take photos and to tag them with “#Activism”? Or was it an invitation to find photos shot by Ai Weiwei by searching for the tag “#Activism”? (Did the exhibition have some online component I was missing, and if so, on which application?) Clearly Mr. Ai’s Instagram activity needs be read in the context of his earlier, analog photography, and the vast gap between how we encounter his photographs on Instagram and in the museum only makes this task more necessary. But Instagram, as opposed to the albums on Google+, or framed photographs on a wall, allows for no backwards editing, and I left wondering how such an insistently present photographic practice might be presented within a retrospective frame.

Postscript / #leggun

The above text was written in early May. As of today, in late June, Mr. Ai has uploaded over 3,500 photographs to his Instagram account, and for the past three weeks, Mr. Ai’s Instagram feed has been overtaken by images of people with one leg raised up in the air, toes pointed, aiming like rifle. Showing kids, adults, individuals, groups, in China, Europe, the U.S., Latin America, some of these images seem to be have been shot by Mr. Ai (his studio or familiar Beijing surroundings are recognizable in the background), while many others appear be “crowd-sourced”—photographs which people have uploaded to Instagram and tagged with #leggun, or #aiww, which Mr. Ai has then reposted to his own account. Sometimes dozens a day appear, deluging my Instagram feed and becoming background noise that I scroll through quickly to get to something more interesting. While evoking Mr. Ai’s earlier photographs of his middle finger held out in front of iconic sights (e.g. the White House), the meaning of this leg gun meme is ambiguous, and in interviews Mr. Ai has been vague and noncommittal when asked about the phenomenon he unleashed: Is it a public protest? A way of marking the twenty-fifth anniversary slaughter of students in Tiananmen square? A reference to female dancers depicting soldiers during the Chinese civil war? Whatever the intent, posing in or uploading one of these photographs seems a way of announcing one’s membership in a sort of unofficial Ai Weiwei fan club. A photographic mass performance, the images convey a sense of taking aim—at people, places, statues, images, architecture—declaring, weakly, the outlines of a community, what one user refers to in a comment as “an army of Instagram leg weapons.”

New York, June 26, 2014

Ai Weiwei: According to What? will be on view at the Brooklyn Museum until August 10, 2014.

Jacob King is a writer and curator living in New York. His texts have appeared in a number of publications, most recently, Texte Zur Kunst, Mousse Magazine, and May Revue.