Akshay Mahajan, The only ones left on the Island, 2022

The city of Mumbai—once Bombay—has long suffered an identity crisis. Before Bollywood and the Bombay Stock Exchange, the rise of cotton mills and Gothic facades, and the fall of the Raj, the territory was a gift, a seventeenth-century dowry from the Portuguese to the British. This rather bureaucratic maneuver set the stage for Mumbai’s many evolutions: first as an archipelago of seven islands, then a colonial port, and then a modern metropolis. With each mutation, a grand narrative was developed and preserved with great care: on paper, celluloid, and stone. But for those willing to look closely, the city is full of cracks.

The historian Gyan Prakash once said that Mumbai “can be read in the detective novel form.” It may not come as a surprise, then, that the protagonist of Akshay Mahajan’s ongoing series To die is to be turned to gold is on a citywide search. Recalling an old urban legend, the title underscores the city’s image as a place of extremes. As the saying goes, those who move here either prosper or die trying, ultimately turning into gold themselves. But ask any Mumbaikar: the dead don’t die so easily.

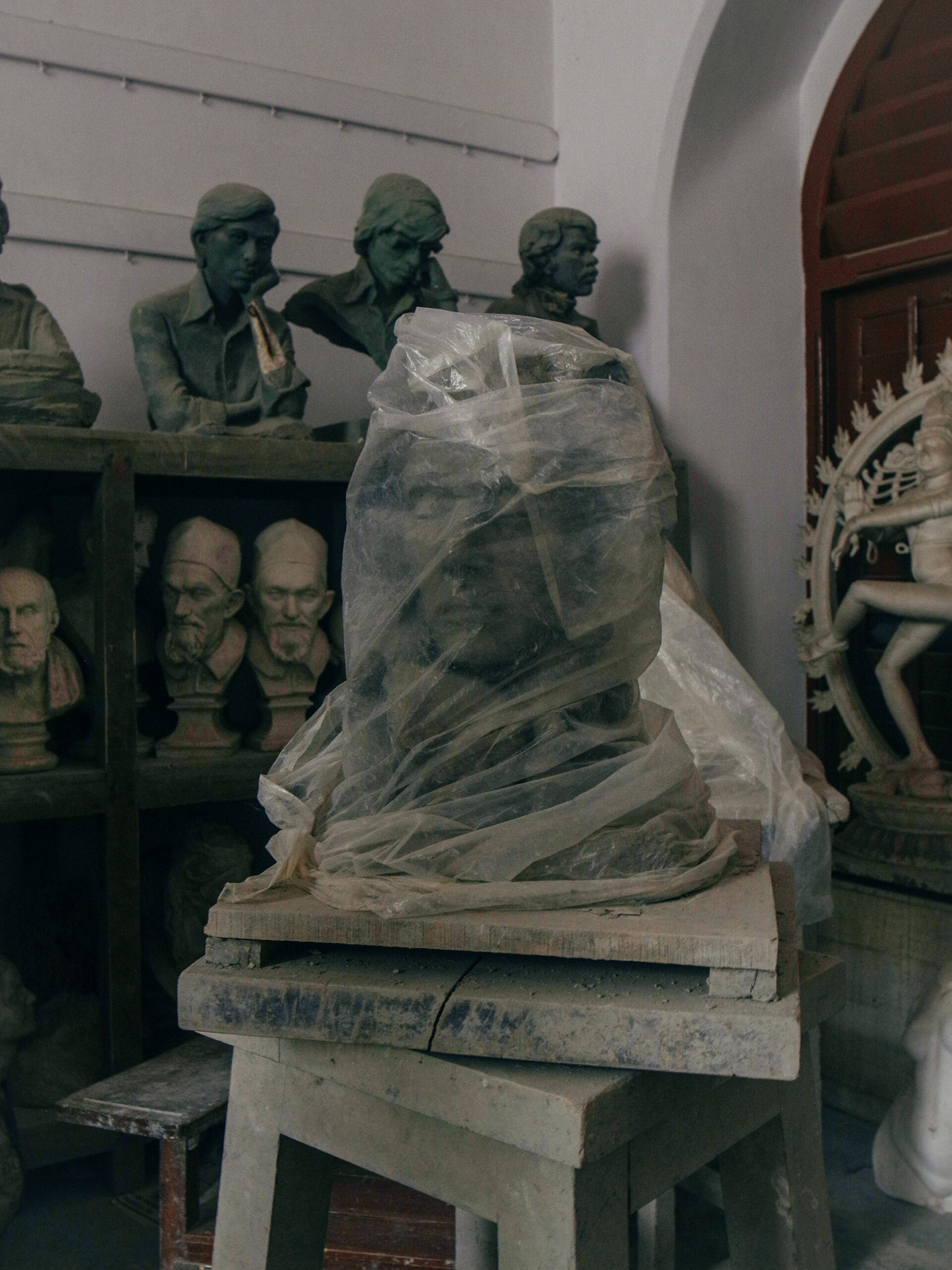

“Within the city’s postcolonial reality is a pre-colonial memory,” explains Mahajan, who called it home before moving down the coast to Goa. “I refer to these as ghosts.” Using a mix of portraits, street photographs, landscapes, and still lifes, he envisions Mumbai through the eyes of a young sculptor who walks the city in search of a muse. One could imagine him as a student at the Sir J. J. School of Art, a pioneering Indian arts institution founded in the nineteenth century, where several photographs from the series are set. The city and school have been historically intertwined; a popular story claims that the gargoyles mounted on Mumbai’s most recognizable Gothic structure, Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus, were student art projects.

For Mahajan—who has a special interest in archives, colonial histories, and urban forms—the series is an experiment with historical continuity and memory. Relics are reinterpreted, replicated, and used as reference material, as the sculptor’s attention seesaws between the colonial and the contemporary, the center and the margins. He understands his debt to Mumbai’s past, but can also intuit its failures and contradictions. In one photograph, Laxmi, a longtime professional nude muse at the school, leans against the plinth of a marble statue. She then reappears in another image as the subject of two student paintings. The sculptor’s eye attempts to preserve Laxmi within the record; instead of disappearing, she multiplies. “There must be a room somewhere with hundreds, if not thousands, more,” Mahajan adds.

New statues emerge, mills are turned into luxury malls, and colonial offices are repurposed as investment banks. Nonetheless, repetitions continue to appear. An image depicting a young student sitting in front of two Greco-Roman replica statues bears an uncanny resemblance to one made over thirty years ago by the photographer Raghubir Singh for his own Mumbai book. All the elements are there: the replicas, the hardwood floor, and nearly the same corner of the sculpture department. Another photograph of a boy on horseback riding into the Arabian Sea seems to mimic an equestrian statue of King Edward VII. Once a centerpiece of the city’s colonial urban plan, the nearly seventeen-foot-tall bronze king now sits in a nearby zoo. If the politics of India is increasingly a politics of revisionism, Mahajan enacts an attentive close reading. “Every successive boom has come at the cost of a class of people who were never pedestalized as statues,” he says. In their search for a Mumbai beyond received frameworks of colonial architecture, art, and commerce, the photographer and his invented guide share the same vision, that “one sculpts bottom up.”

All photographs from the series To die is to turn to gold, 2022–ongoing. Courtesy the artist

Akshay Mahajan is a runner-up for the 2023 Aperture Portfolio Prize, an annual international competition to discover, exhibit, and publish new talents in photography and highlight artists whose work deserves greater recognition.