For Alan Michelson, History Is Always Present

“My work is very much grounded in the local, in place, and place can be fraught when you’re Indigenous,” says the New York–based artist Alan Michelson.

Michelson, a Mohawk member of the Six Nations of the Grand River, has, for more than thirty years, produced evocative, influential works that excavate colonial histories of invasion and eviction. After an early engagement with photography and painting, he gradually shifted to an expanded approach. Video and installation allowed him to abandon a single perspective in favor of unfixed points of view, creating dynamic spaces of visual and auditory immersion. For Alan Michelson: Wolf Nation, his solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 2019, he deployed the panoramic form, which he likens to wampum belts—beaded sashes used by Native nations in diplomacy. The show parsed history with references to maps and other archival materials, and to Indigenous geography and philosophy, challenging viewers, via augmented reality, to reconsider the museum’s location, once a Lenape site where tobacco was grown for ceremonial use. For Michelson, history is always present, unfinished business demanding our attention and redress.

This spring, during the city’s shutdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic, he spoke with the curator Chrissie Iles about his artistic development, the power of contemporary Indigenous art, and the historical echoes of our public health crisis.

Chrissie Iles: In all your work, whether in photography or the moving image, you subvert the camera’s history as an instrument of colonialism by transforming the colonial gaze. What is your relationship to the camera?

Alan Michelson: I got a Nikon camera in my early twenties, at that exciting time in the mid 1970s when Susan Sontag’s On Photography (1977) was current. I was always very visual, always drew and painted, and soon became absorbed in that heightened mode of seeing through a viewfinder. I was living in coastal New Hampshire and would go for long walks and take pictures.

The color in the world was really attracting my eye, moody colors and motifs with implicit references to landscape painting and abstract painting. Later, at the Boston Museum School, many of my teachers were from the generation of Abstract Expressionism and Color Field painting, when artists had turned away from external representation to an internal set of coordinates, where color and gesture were more important.

Iles: How did your work develop after art school?

Michelson: After art school, I gradually moved away from the vertically oriented pictorial space of painting to the receptive, horizontally oriented space that Robert Rauschenberg opened up, Leo Steinberg’s “flatbed picture plane,” where photographic imagery could become palette and two-dimensional imagery could coexist with objects. The kind of space that when applied to a room became installation. And I was fascinated by the possibilities of site specificity, because I’ve always been attracted to history as much as to form. I cycled through all of that to installation, and started really thinking about how history had treated Native people.

Iles: How did Indigenous knowledge systems, survivance, and a resurfacing of suppressed histories become the substance of your work?

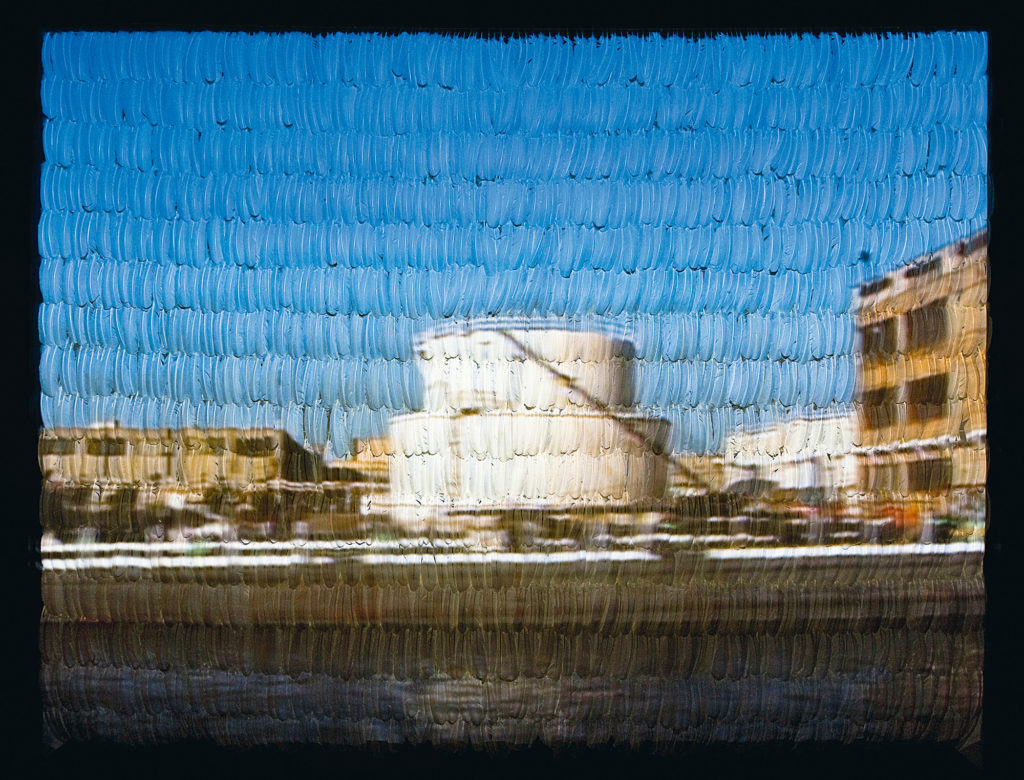

Michelson: I would say that some of my recent work has its roots in my first video, Mespat, which was made in 2001. Valerie Smith invited me to participate in Crossing the Line at the Queens Museum and make work based on the borough of Queens. I was interested in looking at its shoreline from a boat, from the viewpoint of the early explorers, as well as of my ancestors, because waterways were really the highways in those days. It’s not a view that you often see. And I also wanted to reference moving panoramas of the nineteenth century, the ones that simulated marine travel.

So I mounted a camera on a boat and sailed up Newtown Creek, an industrial waterway contaminated by more than a century of oil spills, chemicals, and sewage, a Superfund site. The marine mount enabled a smooth, continuous dolly shot of more than three miles of its shoreline, including scrapyards, bridges, and refineries. I was aware of Michael Snow’s Wavelength (1967) and Andy Warhol’s Empire (1964), and like those films, there was a banal aspect to it. I was just observing what was there. And what was there was a stark catalog of industrial life and death, with the hopeful exception of a white egret.

Iles: You described your engagement with photography in the ’70s, at a moment when photography was an important conceptual medium, especially for Land art and Land artists. What do you think about the ways in which Land art often ignored Native American history and presence?

Michelson: Well, colonists assumed the identity of “Americans.” For Euro-Americans, that meant an entitled legacy, to imagine that the land was American land and no longer Native land with a history. The dearth of historical context in Land art seems to reflect that sense of entitlement, as does its unacknowledged but obvious debt to Native mounds and its sheer grandiosity. However, there’s also a dystopian undercurrent in Land art that can even be seen in the work of Hudson River School painters like Thomas Cole. My favorite work of his is The Course of Empire series (1833–36), in which he painted an imagined landscape and charted its evolution from “The Savage State” to its own self-destruction.

Iles: Do you think there’s a relationship between that moment and today?

Michelson: Yes, in this current mess that we’re in with COVID-19, Cole’s allegory has never rung truer. This pandemic is coming from the cross-species migration of a viral infection from animals to humans. Eurasian farming resulted in humans living intimately with animals for thousands of years, during which time those large mammals had viral infections that they passed to human beings, the source of epidemics to which European and Asian people eventually built up immunity.

But conditions here on Turtle Island, our name for North America, were very diff erent, and there were really no domesticated mammals here besides the dog. So, our people had no immunity. To them, the diseases that came over with the colonizers—smallpox, measles, the flu—were deadly, novel viruses. The entire world is now experiencing what our ancestors experienced when European colonizers invaded.

Iles: How does this manifest in Mespat?

Michelson: I was interested in the way that the colonial gaze became an American gaze that didn’t acknowledge itself as colonial; it conceived of itself as entitled. And that colonial sense of entitlement is present not only in landscape painting but in off shoots like panoramas, which offered virtual means of touring “exotic” places minus the expense or risk. Mespat is a counterpanorama, in video pixels and feathers instead of paint, of colonial displacement and destruction.

Iles: Clémence White points out in her essay “Alan Michelson: Site Readings” for the 2019 Whitney exhibition Alan Michelson: Wolf Nation that the horizontality in your work “centers Haudenosaunee culture through its relationship to the wampum belt,” and “Haudenosaunee theology, which proposes that the ‘interconnectedness of all life is sacred and key to human freedom and survival.’” Panoramic photography was very popular in the nineteenth century as part of opening up the world and, at its root, is colonial. You use this perspective as a form of resistance by applying it back to a kind of ethical and social interconnectedness of Native American philosophy and spirituality.

Michelson: Extreme horizontality, extension in space, is always extension in time. Viewing panoramic work entails movement and perspectival shifts, the experience of multiple vantage points rather than a single fixed one, which is consonant with the egalitarianism of Native communities. Also, immersive work becomes interactive, a dynamic environment that activates a dialogue, or a set of relations, reflective of our relational epistemology. My appropriation of colonial formats is informed by those ethics. What do they call it when people restage Civil War battles?

Iles: Reenactments.

Michelson: Yes! Then you could say that my sailing up Newtown Creek, retracing the route taken by the first colonists of what became Queens, was a reenactment. If you can keep 1641 [the year before the colonists displaced the Mespeatches] in mind in 2001, it sets up a dialectic between what you see in 2001 and what was there in 1641.

I’ve also been fascinated with wampum belts, a powerful Haudenosaunee and Eastern Woodlands cultural institution, belts made up of hundreds of shell beads, purple and white, that were used to seal agreements. They were documents, codes, even, but they also embodied the natural world because they were made of the shells of animals. They were also collective works, originating in shellfish gathered by the people as food, recycled as beads, and then woven into patterns that carried messages. I based a four-channel video piece, TwoRow II (2005), on a key wampum belt, the Kaswentha, also known as the Two-Row Wampum. In 1613, we made a trading agreement with the Dutch symbolized in the belt by two rows of purple beads separated by three rows of white. The purple rows represented the parallel courses of two vessels on a river, our canoe and their sailing ship, and the white rows peace, friendship, and mutual respect. In my piece, filmed from a tour boat on the Grand River at Six Nations Reserve, there are two rows of panoramic video moving in opposite directions, one of the non Native townships on the east bank and the other of the reserve on the west, with a soundtrack featuring conflicting narratives about the river—that of a Canadian tour-boat captain and those of Six Nations elders.

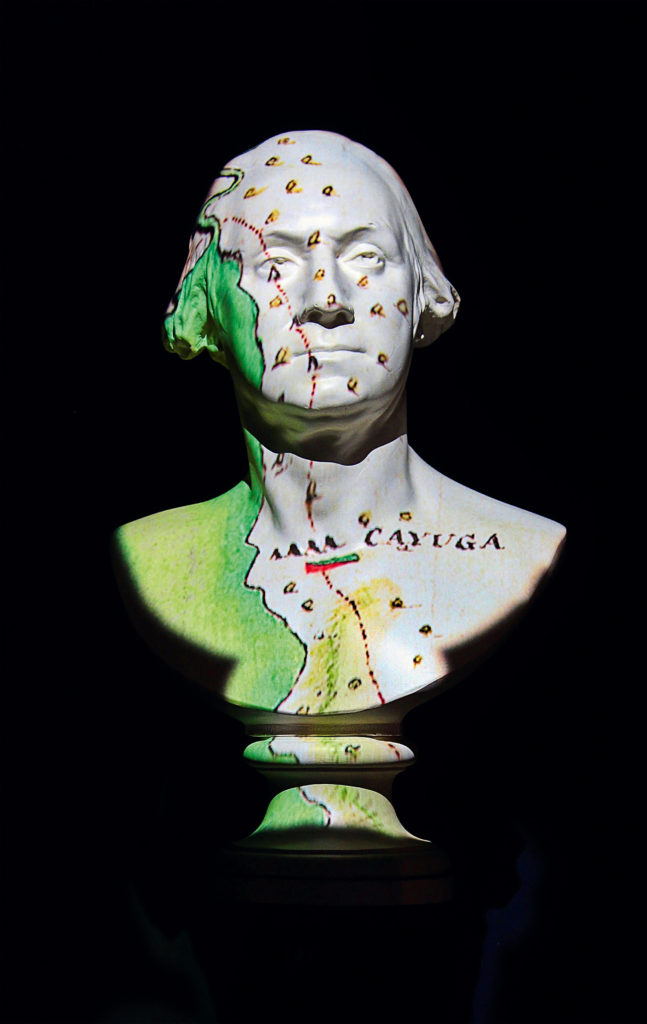

Iles: For your works Hanödaga:yas (Town Destroyer) (2018) and Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Theatre of the World) (2019), which Zuecca Projects showed in Venice last year, you combine the photographic image with maps, drawings, and sound in a form of collage that operates as a resistance to surveillance and a single viewpoint. How do you use the photographic image and the archive to resurface memory and history?

Michelson: Photographic imagery and its documentary aspect are important in my work, both in its moving and still form. I like to use the archive against itself, to challenge the colonial narratives it usually serves. Hanödaga:yas (Town Destroyer) is a projection onto an iconic bust of George Washington by the French sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon. In 2018, the approaching 240th anniversary of Washington’s 1779 destruction of Iroquoia—our extensive homelands in what is now New York State—prompted me to get a life-size replica bust and project archival imagery onto it to tell the story of invasion and forced eviction. The imagery includes historical maps and New York State historic markers, which seem to celebrate genocide, commemorating, for example, “Site of Catherine’s Town, destroyed 1779 by General Sullivan.” My video pans over the map of the campaign, pausing at the places where Washington’s armies destroyed Iroquois villages, all of it playing out over his face. One of my goals is to defeat American amnesia and denial.

Iles: You use three-dimensional surface and form to deepen and trouble the storytelling of the projected image. How did this work in your Venice piece Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Theatre of the World)?

Michelson: Well, the exhibition was about Venice’s role in the early exploration of the Americas.

I had the idea of projecting archival material onto a globe, because that’s essentially what European exploration was—global projections of European power and avidity.

Then I had the idea of doing four of them, referencing the Four Directions and a chart from Andreas Cellarius’s 1660 celestial atlas, Scenographia Systematis Copernicani, depicting four hemispheric globes illuminated by a central sun. I thought, Well, I could do something like that by projecting video onto four spheres.

The first surface I projected onto, in Mespat, was the shallow convex surface of white turkey feathers. The second was the more complex dimensionality and iconography of the bust of Washington. The third was an ideal form, the sphere, but also the form of the world. I’m getting more grandiose as I progress.

Iles: This progression is creating what could be described as an Indigenous cinematic. You are rewriting the parameters of the Western history of cinema—a single rectangular screen with a fixed frontal viewpoint and fixed seating—by inscribing Indigenous value systems of horizontal power, shared space, and cyclical time into the projective space. Your use of diff erent material forms as projective surfaces also reframes the cinematographic as something that’s not defined by the West or by American and European—

Michelson: Rectilinearity.

Iles: Yes.

Michelson: Western architecture’s basic program. And of the grid system settlers applied to land, the checkerboards visible from airplanes.

Iles: Last October, during your exhibition at the Whitney, we organized a panel on contemporary Indigenous art in a global context, in which we considered Indigenous communities as the first global communities and discussed their relationships to one another.

Michelson: Both of my fellow speakers at that panel, the Australian Aboriginal artist Richard Bell and the Anishinaabe curator Wanda Nanibush, had previously participated in a 2017 initiative called “Indigenous New York” that I founded and curated with the Vera List Center for Art and Politics, which opened up space for contemporary Indigenous art in New York. The vitality of global Indigenous art was not registering on New York’s radar, and we were trying to save New York from self-fossilizing! Certainly in other places, including Australia, New Zealand, and Canada, Indigenous art was more visible. We hosted some seminal discussions between Indigenous curators, critics, and artists, and their non- Indigenous counterparts. Contemporary Indigenous art is on the rise these days. It has the power not only of aesthetic beauty but of ethics and calling for justice, which are also beautiful.

Iles: Those discussions underline the powerful role photography and the moving image can play as forms of witnessing. The use of the camera as a witness obliges you to think about who is behind the camera, and how that operates in an environment in which democratic image making and the circulation of images through social media challenge official versions of whatever the truth might be. The vertical perspective of drones, which takes the camera away from the eye and the body, into a disembodied space of surveillance—

Michelson: Which can also be a military space.

Iles: Exactly. It seems that the ethics of the photographic or cinematographic image are even more compelling than ever.

Do you think the current COVID-19 crisis will change us all forever and the world forever? How do you see it affecting your work and your thinking?

Michelson: I think this crisis is brushing back a lot of the sense of entitlement that people have, maybe making them think more about the planet and our interconnectedness. It’s laying bare gross folly and injustice. I’m agitated by the fact that another raging pandemic is devastating Native people, descendants of the victims of so many previous epidemics of deadly diseases brought to Turtle Island, and that once again the federal government is not delivering on its treaty obligations.

Iles: That shared space can be both Indigenous and non-Indigenous, which seems even more important in relation to what you posted about Indigenous communities not being recognized in government statistics about COVID-19.

Michelson: Yes, even in New York, a liberal city with the highest population of Native people in the country. Right now, in May, the infection rate of the Navajo Nation has surpassed that of New York and New Jersey. Due to the ongoing effects of colonization, Native people are a hugely high-risk group, and they’re not getting direly needed supplies in Indian country.

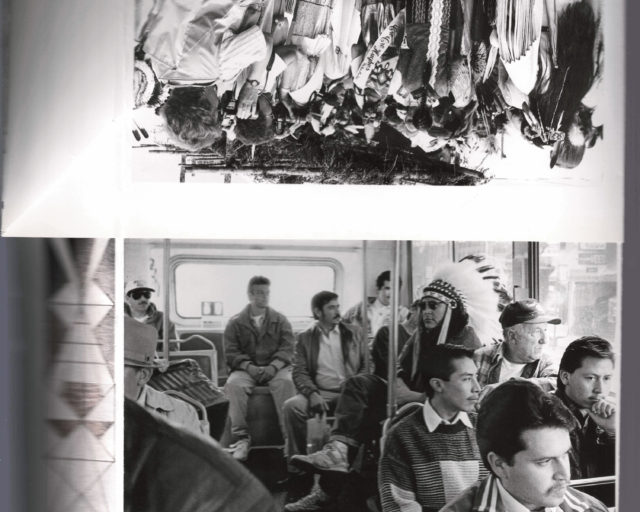

Alan Michelson, Still from Wolf Nation, 2018. HD video, with sound by Laura Ortman

Iles: Which means that the communities are effectively absent, and therefore don’t exist, and cannot get the support they need to fight the virus. The pandemic is exposing, in stark terms, the economic and political realities of inequity.

Michelson: I’m amazed, Chrissie, how the nineteenth-century trope of the “vanishing Indian” persists, and how government policy continues to reflect that.

Iles: Yes.

Michelson: In times of crisis like this, will doors that have been recently opening close again, and will there just be a reassertion of privilege by those who are most privileged? That can happen on so many levels beyond the art world.

Iles: Yes. This situation is a dress rehearsal for what’s coming in terms of climate change.

Michelson: The signature work in my Wolf Nation exhibition was my 2018 video of that title, which I made for the Indicators: Artists on Climate Change exhibition at Storm King Art Center. People wonder about when and how wolves became dogs. I was thinking about the wolves of Turtle Island, and how we have wolf clans and a profound sense of kinship with animals. Through the cooperative model of the wolf pack, wolves may have taught human beings how to hunt, which is a huge thing, if you think about it. And yet, wolves, like Native people, were themselves hunted and removed. As is clear from converging crises, we urgently need to confront our tortured history and our disastrous leadership, and rethink our current political, economic, social, and environmental models. Indigenous models, including those of survivance, active presence, and resistance, provide an alternative.

Iles: Absolutely. Your work embeds a new social ethics of survivance in the screen, the camera, and the projective space. The old social, political, and cultural models don’t work and are disintegrating. We are entering a new reality, and culture is changing fast. Your work is a map that can help us navigate a different kind of future.

This interview was originally published in Aperture, issue 240, “Native America,” under the title “History is Present.”

All works courtesy the artist.