Our Births, Ourselves

Carmen Winant’s archive considers the terrors and pleasures of childbirth.

Carmen Winant, My Birth, ITI Press, 2018

I have feared childbirth since it was first explained to me in graphic detail at the age of ten. Twenty-seven years later, I find myself a childless woman of a certain age, by which I mean a woman on the verge of the inability to define oneself as a biological mother (and, perhaps, less of a woman in the eyes of my mother, some friends, or certain colleagues who suddenly and increasingly ask if I want kids). Will I experience childbirth before it’s too late? Could it be as terrible as I imagine? Do I have the hips perfect for birthing, like my mother does?

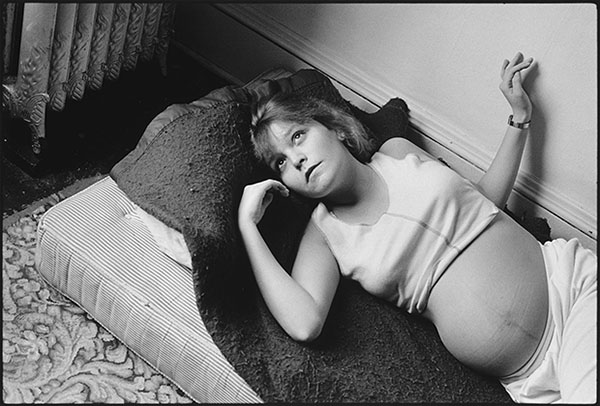

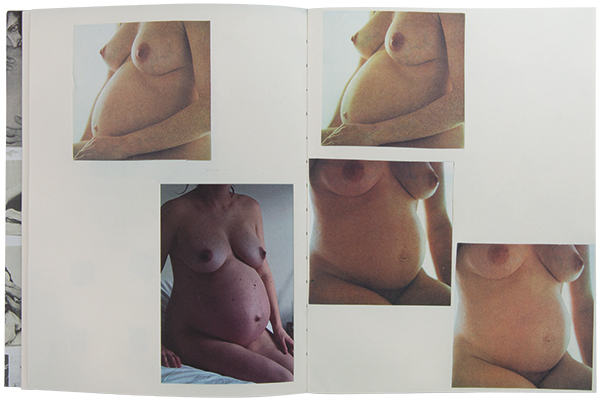

Carmen Winant’s brave, forceful project My Birth presents its own line of inquiry about childbirth, but it approaches the subject from the peripartum perspective. Produced between her first and second pregnancies, her book begins with a slate of fifty-four questions that range from “Has there ever been so much unknown?” to “What did you do with your hands?” What follows is a cascade of found photographs of women (often shown alongside their partners, doctors, nurses, friends, and midwives—the otherwise invisible community that surrounds birth) in various stages of pregnancy and labor, sequenced from gestation to postdelivery. Winant sourced many of these images from what she describes as “deaccessioned material”—from magazines, pamphlets, and even books such as Our Bodies, Ourselves. Also featured among this selection are photographs of Winant’s own mother, whose three births were documented in pictures that Winant discovered in her parents’ bedroom.

The images in My Birth are challenging and oddly unfamiliar despite the ubiquity of what they depict. Women appear unladylike, uncomfortable, unglamorous, and unposed. Bodies contort in strange positions in response to crippling pain and the need to control the pace of labor. There are placentas, epidurals, infants crowning, and cervixes spread wide. There are inscrutable scenes of medical procedures and activities presented without captions or explanations. And the chaos of the process laid out before us foreshadows the difficulty of raising children, something established at the moment of birth.

The act of looking at these pictures mimics the experience of active labor—they invite us to slow down, feel squeamish, and flip quickly past the more visceral images as if we are bearing down during a contraction that we hope passes soon. Those who visit Winant’s powerful presentation of this project in the exhibition Being: New Photography 2018 at the Museum of Modern Art (on view until August 19, 2018) can witness the birthing process take on a more physical form: museumgoers will encounter more than two thousand photographs fastidiously taped up on two walls of a corridor, effectively simulating a birth canal, facilitating passage between the galleries that showcase the exhibition.

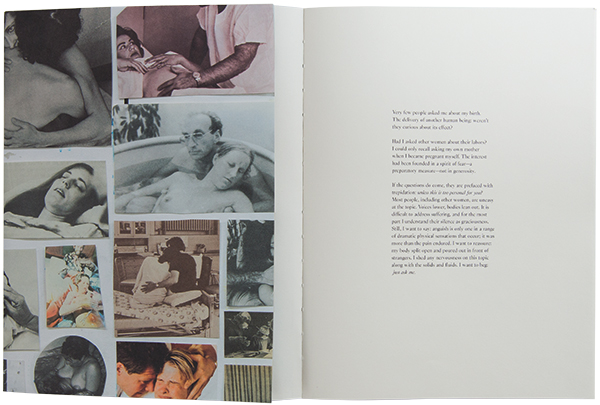

With this book and the related installation at MoMA, Winant has made visible a process that, as Robbie E. Davis-Floyd stated in Birth as an American Rite of Passage, is “rarely lived out in the public or peer domains.” Moreover, the limited representations of pregnancy or childbirth that exist in the public consciousness (think Lennart Nilsson’s photograph of a fetus on the cover of Life in 1965, or Stan Brakhage’s short film Window Water Baby Moving, 1959, of his wife in labor with their daughter) have typically been produced by men. This begs the question as to why, a curiosity that drives Winant’s exploration. In the eloquent text included in her book, Winant posits that “childbirth has not successfully been contained or described by means of secondary depiction,” whether visual or verbal. The lexicon specific to childbirth, for example—which includes words or phrases such as “delivery,” “labor,” and “giving birth”—fails us, obfuscating the trauma and physical pain associated with this experience. Winant struggles with the notion that there is “no language” to accurately describe the pleasures and terrors of childbirth, wondering if it is “too big for words.” However, her own musings in My Birth amount to an impressive creation, one that conjures Hélène Cixous’s conflation of writing and childbirth, activities described as similarly physical, muscular exercises. In her essay “Coming to Writing” (1991), Cixous states: “She gives birth. With the force of a lioness. . . . She draws deeply. She releases. Laughing. And in the wake of the child, a squall of Breath! A longing for text! Confusion! What’s come over her? A child! Paper! Intoxications! . . . Milk. Ink.”

Reflecting on the birth of her first child, Winant recognized a similar twinning effect: “There is no other way to say it: when I gave birth, I also experienced my own deliverance.” Viewed in the context of Betty Friedan’s belief that “the only way for a woman, as for a man, to find herself, to know herself as a person, is by creative work of her own,” Winant has effectively spawned her third child with the publication of My Birth. Employing the possessive pronoun “my” in the book’s title, Winant confirms ownership—she has composed this work, introspective and intimate, for herself. But as with her children, she has also released this one-time possession into the world, something she wants to be shared with many people. “Is birth a process of connecting to our bodies, or of leaving them far behind?,” Winant asks the reader as much as she asks herself, only to land at the conclusion on the final page that she is “no closer to understanding who takes possession of this process, or locating the words to make it known.” The candor present in her concise text, combined with the unvarnished images she thoughtfully selected for us to inspect, fosters a dialogue that feels groundbreaking and vital. In the end, we have all experienced birth. We shouldn’t be afraid to study it or discuss it. As Winant declares in the preface to My Birth, “I shed any nervousness on this topic along with the solids and fluids. I want to beg: just ask me.” Come in, join me, the water is warm and already broken, she assures us.