Aperture #214—Editors’ Note

The following first appeared in Aperture magazine #214 Spring 2014. Become a subscriber today!

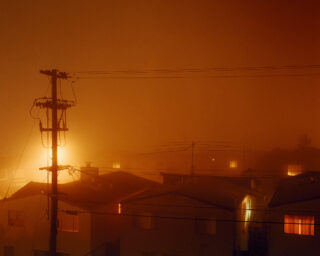

Zeng Xian Fang, Xiaobeilu, Guangzhou, China, 2012

“We know photographers make frames, but we deeply believe they can also create frameworks,” guest editor Susan Meiselas remarks in this issue, while discussing with Chris Boot, Aperture’s executive director, how documentary photographers might adapt to a field that has been transformed over the last decade by radical technological advances. Last spring, Susan and her colleagues—Emma Raynes, director of the Emergency Fund for the Magnum Foundation; Open Society Foundations’ Documentary Photography Project; and Wendy Levy of New Arts Axis organized a conference called “Photography, Expanded.” Over two days, nearly three hundred photographers, technologists, writers, and thinkers gathered at Aperture’s gallery and discussed forging new paths through a field shaken by the disappearance of traditional models. We picked up the thread of the debates and questions raised during the conference by inviting Susan and Emma to help us assemble this issue of the magazine.

In Words, we learn about the function of citizen journalism, the benefits of and problems with image aggregation, the changing role of the professional documentarian, developments in social-media visualization and mapping, as well as the shifting meanings of the word document. This decade of photographic flux has coincided with years of economic and social instability. References to global events conflicts, protests, civil war—defined and facilitated by novel uses of images and media echo across these pages. We also hear a good deal about the massive volume of photographs produced today. The idea that we’re oversaturated with images has become reflexive. But as theorist Thomas Keenan comments in his exchange with artist Hito Steyerl: “There have always been too many words and too many images and too many sounds to … figure out what’s going on.” Hence, he continues, the need for documents, debate, and politics.

For Pictures, we sought out sociopolitical projects that couldn’t have been made ten years ago and that offer fresh models and strategies for producing work. Many utilize new media, stress interactivity, and engage audiences by enabling them to participate. James Bridle capitalizes on Instagram and Tumblr as vehicles for reporting the ongoing drone war. Thomas Dworzak switches from photographer to editor with his “Instagram Scrapbooks,” which expose surprising political dimensions in the imagery uploaded to the popular platform. One scrapbook, featured on our cover, comprises posts from Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov. An avid Instagrammer, Kadyrov commented in the Guardian on the platform’s political value: “I now have the opportunity to monitor public opinion in real time.” For a leader accused of human rights abuses and ruthless dealings with political opponents, the feed might also be viewed as a means to soften his image (he has penchant for posing with animals) or simply as an expansion of a cult of personality through social media.

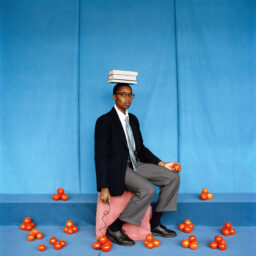

Another twenty-first-century phenomenon—African laborers in southern China—is addressed by Daniel Traub’s Xiaobeilu project (seen above). For this, he has engaged two local itinerant Chinese photographers and provided them with hard drives to build an informal archive of a new immigration trend. Collaboration likewise informs Wendy Ewald and Eric Gottesman’s portfolio, as well as Emily Schiffer’s project See Potential on Chicago’s South Side, which employs photography, mapping, and data collection to draw attention to underserved communities.

Indeed collaboration—between photographers, between photographer and subject, or between image-makers and participating audiences—is a recurrent theme. Theorist Ariella Azoulay observes in her conversation with curator Nato Thompson that “collaboration has always existed in photography but it is usually denied.” Azoulay then stresses the current prevalence of the prefix “co-” in terms of colaboring and cothinking. Fitting, then, that this issue was a collaborative endeavor, one of pooling and weighing ideas as a team, aiming to chart a transformed—and still transforming—terrain for socially engaged visual storytellers.

—The Editors