Arbus Before Arbus

Diane Arbus, Jack Dracula at a bar, New London, Conn., 1961 © The Estate of Diane Arbus, LLC

Diane Arbus was looking for a mirror. By 1967, when her photographs were included in New Documents at the Museum of Modern Art, that search had settled into an intricately artificial kabuki of performed self-awareness. The photographer’s presence in her subject’s gaze was just as important as the subject’s presence in hers. But in the Met Breuer’s cautiously stunning new exhibition, diane arbus: in the beginning, she is just learning to catch a stranger’s eye. This show, curated by Jeff Rosenheim, consists of more than one hundred velvety, black-and-white photographs shot and printed by Arbus between 1956 and 1962 and mounted, each in its own spotlight, on an expansive zoetropic stagger of individual panels clipped between ceiling and floor. The lion’s share of the prints belongs to the Diane Arbus Archive, Doon Arbus and Amy Arbus’s 2007 gift to the Met, and has never been shown before.

At the very beginning, it seems, Arbus was barely there herself. Frozen tableaux showing the mechanics of representation—like the sharp-edged light of a movie projector hanging across a theater, or Bela Lugosi as Dracula on television (1958)—alternate with minuscule sparks of mutual recognition. Boy Stepping off the Curb (1957–8) looks as if he’s just seen a ghost, while Blonde receptionist behind a picture window (1962) confronts the same ghost with more sangfroid. Little man biting woman’s breast (1958) gazes into the lens like a child making sure his mother’s still watching, while Woman in white fur (1958) is haughty and indignant.

Diane Arbus, Lady on a bus, N.Y.C., 1957 © The Estate of Diane Arbus, LLC

Of course they’re all just reacting to the camera. But Arbus makes these fleeting, fragmentary reactions into incandescent moments of radical self-consciousness, sudden shocks of lucidity in the long waking dream of life. She pours so much desperate attention through her lens that some of it is bound to bounce back; even the carcass in Dead pigs hanging (1960) is animated and human. This exhibition also includes an annex of two unfortunately didactic rooms that display a handful of works by Arbus’s contemporaries (such as Garry Winogrand) and influences (August Sander), as well as some of her own later, more famous work. But those long-canonized pictures only serve to distract from the fresh, unexpected sincerity of Arbus’s early forays into the form.

Sometimes a flickering encounter is broad enough to support a textured revelation. Taxicab driver at the wheel with two passengers (1956), for example, is a chamber drama. A male passenger on the far side is confident and self-contained. His female companion, in the near window, is also self-contained, but hers, as she bites a thumbnail and burns down a cigarette, is a bubble of anxiety. And the driver, our Virgil through the ecstatic chaos of New York, looks at the camera with a confidently hopeless camaraderie, as if to say, Here’s another poor soul who can’t help me and whom I can’t help.

Diane Arbus, Taxicab driver at the wheel with two passengers, N.Y.C., 1956 © The Estate of Diane Arbus, LLC

And sometimes the flickers burst forth into fully formed portraits of people on the social fringes: the Human Pincushion, the Madman from Massachusetts, the Man Who Swallows Razor Blades, socialites, female impersonators, and a host of others—all living symbols of the alienation of being alive. But why did such serendipitous candid shots become, in Arbus’s later phase, posed portraits? Did Arbus’s search for connection simply crystallize into an empty ritual? Or did her fascination with unique human expressions curdle into a kind of nihilistic cynicism? At times, Arbus’s view shifts from the humanely documentary to a baffled disbelief in our shared social conventions, the language we use to live and communicate. A gaping old woman in her hospital bed, for example, looks as if she’s faking for the camera, or wax-work, and several shots of adults carrying sleeping children like corpses in their arms seem to imply that death itself is nothing but another false performance.

Miss Stormé de Larverie, the Lady Who Appears to be a Gentleman (1961), which shows a slender woman in a dark men’s suit, black boots, and a thin black tie sitting on a park bench, demonstrates what happened. The photo’s narrow palette and shallow depth of field flatten the bench and tilt the lawn and concrete walkway upward, as if all of Central Park were nothing but a painted backdrop in an indoor studio. Miss Stormé’s pose is casual but deliberate, self-possessed but carefully defended: she leans forward slightly, facing the lens but not quite looking into it, turns her crossed legs almost sideways, and crosses her hands over her lap for good measure. On her left hand is a pinky ring and a wristwatch. A cigarette burns between her fingers.

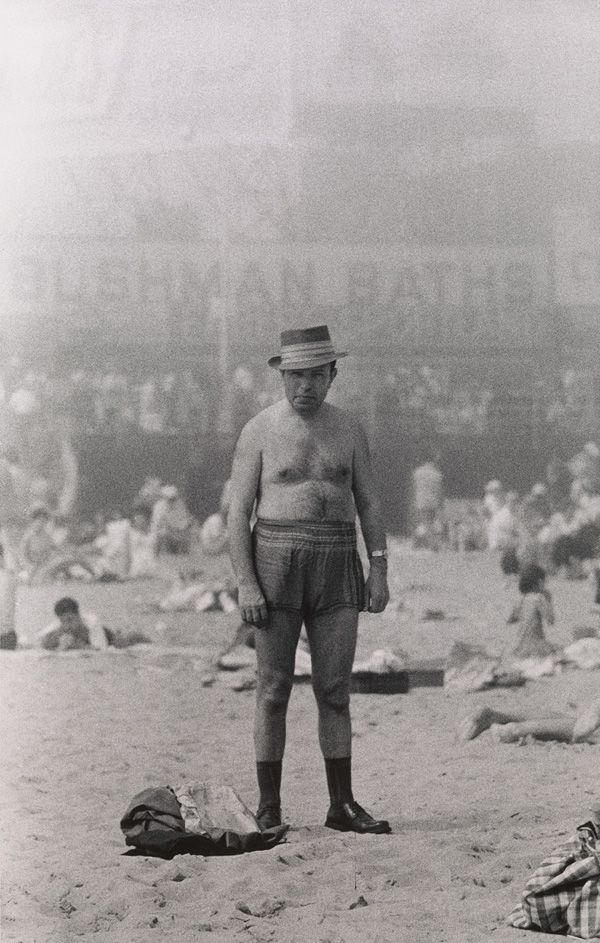

Diane Arbus, Man in hat, trunks, socks and shoes, Coney Island, N.Y., 1960 © The Estate of Diane Arbus, LLC

The photograph amounts to a collaboration, a relic of Arbus’s and de Larverie’s temporary agreement to create a particular character. But this kind of connection between Arbus and her subject is one that comes at the expense of their connections to anything else. What happened is that Arbus’s instinct for the spontaneous and human transformed itself, through an escalating cycle of self-consciousness and introversion, from a search for meaningful encounters to a method of entombing them. By the time she found her mirror, her vision was too sharp.

diane arbus: in the beginning is on view at the Met Breuer through November 27, 2016.