The Architecture of Desire

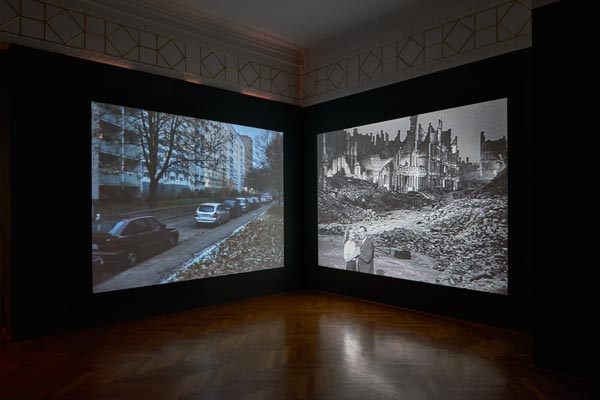

Amie Siegel, Circuit, 2013. Installation view, Ricochet #10: Amie Siegel, Double Negative, Museum Villa Stuck, Munich, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Simon Preston Gallery, New York

The word “ricochet” describes a moving object—such as a bullet—which, when hitting a surface, fails to penetrate it, and instead rebounds at an angle. It’s appropriate that Amie Siegel’s first large-scale survey exhibition in Germany, Double Negative, is presented as part of Ricochet, the exhibition series at Munich’s Villa Stuck, a museum housed in the former mansion of German fin-de-siècle painter Franz von Stuck. Like a ricocheting object, the power of Siegel’s works comes at you tangentially and strikes with unexpected force.

Amie Siegel, Double Negative, 2015. Installation view, Ricochet #10: Amie Siegel, Double Negative, Museum Villa Stuck, Munich, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Simon Preston Gallery, New YorkSiegel’s seven works on view—in video, film, and photography—provide thorough insight into an artistic practice often considered an “interrogation of cinematic tropes.” Double Negative also reflects on, plays with, and undermines the narrative and formal strategies of visual storytelling and its media, as well as the iconography of the moving image. Yet that would discount, even ignore, the precise curating of Yara Sonseca Mas and Siegel herself and their nimble use of the villa’s challenging, ornately decorated, rooms. Over the course of the exhibition, each of Siegel’s works gradually resonates with one another to reveal their Janus-like nature.

Amie Siegel, Double Negative, 2015. Installation view, Ricochet #10: Amie Siegel, Double Negative, Museum Villa Stuck, Munich, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Simon Preston Gallery, New York

Rich and multi-layered in aesthetic and content, Siegel’s art observes the social and economic patterns that form and influence our relationship with object and image, architecture and archive. A meticulous image maker, precise in her framing and construction of thought-provoking tableaus, she questions our often-fetishistic habit to assign myths to material objects and thereby establishes both personal meaning and commercial value. Siegel illustrates this instinct explicitly in Provenance (2013), the first piece on view.

Amie Siegel, Provenance, 2013. Installation view, Ricochet #10: Amie Siegel, Double Negative, Museum Villa Stuck, Munich, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Simon Preston Gallery, New York

As the title implies, Provenance, a 40-minute HD video traces an object’s history, in this case the global trade of collectible designer furniture, mainly chairs and stools, to their origin at Chandigarh—the controversial 1950s modernist city in India, conceived by Swiss architect Le Corbusier—all the way down to its furniture. In reverse chronology, the video’s slow, opening tracking shots of upscale Western residences—the furniture’s present settings—proceed backward through auction previews and sales, photo studios, restorers’ workshops, shipping containers, and finally into Chandigarh’s office complexes, where the furniture originated.

Amie Siegel, Provenance, 2013. Installation view, Ricochet #10: Amie Siegel, Double Negative, Museum Villa Stuck, Munich, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Simon Preston Gallery, New York

Siegel’s complex power of observation lies not in offering judgment, but in a seemingly objective, almost passive presentation, a strategy of indirect disclosure. Provenance, however, has been unjustly criticized for its high-end aesthetics, and for obscuring details about locations, dealers, and collectors, and particularly for exploiting the insular logic of the art market. After the first exhibition of Provenance in New York, Siegel later auctioned off an edition of the video at Christie’s in London—and filmed the entire process. The result, Lot 248 (2013), retelling the preview and auctioning of Provenance, and Proof (Christie’s 19 October, 2013) (2013), a framed printer’s proof of the auction catalogue’s page for the Provenance lot, are also exhibited in Munich. Taken together, the entanglement of Provenance with the art market is merely a feint to decode something else: following our desire to possess or belong, objects become actors—or surrogates.

Amie Siegel, The Modernists, 2010. Installation view, Ricochet #10: Amie Siegel, Double Negative, Museum Villa Stuck, Munich, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Simon Preston Gallery, New York

A more intimate and humorous facet is present in The Modernists (2010), scenes from vernacular photographs and Super 8 films, made by a couple from the 1960s to the ’80s, who traveled to the world’s major museums and iconic art sites and posed with famous sculptures. Displayed in the villa’s remarkable former bathroom (with fragments of an antique frieze affixed to its walls), it subtly prompts questions about class, about economic power and the accessibility of culture, and the shifting status of souvenirs—from historic objects to photographic performance.

Amie Siegel, The Modernists, 2010. Installation view, Ricochet #10: Amie Siegel, Double Negative, Museum Villa Stuck, Munich, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Simon Preston Gallery, New York

Berlin Remake (2005) is a double-projection of scenes from films by the former East German State Film Studio, juxtaposed with her present-day “remade” versions. Deathstar/Todesstern (2006), five screens of slow-motion shots traveling through hallways of early German modernist buildings, constructed or appropriated by the country’s totalitarian regime, are loops that viewers can enter into at any point. Devoid of narrative, with no explicitly theatrical motivation or plot, they prompt viewers to confront the uncanny, somewhat menacing, architecture itself, and thereby reveal how our reaction is directed, if not manipulated by, the camera.

Amie Siegel, Berlin Remake, 2005. Installation view, Ricochet #10: Amie Siegel, Double Negative, Museum Villa Stuck, Munich, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Simon Preston Gallery, New York

The nexus of this exhibition’s cross-referential net is Double Negative (2016), a new two-part work commissioned by the museum. Two facing, 16mm films simultaneously project images of Le Corbusier’s all-white Villa Savoye, now a museum near Paris, and its all-black “replica” in Australia, which houses an aboriginal archive. As both films are projected from negative stock, our notions of original and copy, of black and white, are confused, and we are left to find our own answers of intent and meaning. The second part, a color video of the interior of the Australian archive, shows, in a melancholic tone, its ongoing digitization of ethnographic films and aboriginal cult objects.

Amie Siegel, Double Negative, 2015. Installation view, Ricochet #10: Amie Siegel, Double Negative, Museum Villa Stuck, Munich, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Simon Preston Gallery, New York. All installation photographs by Jann Averwerser

The questions ricocheting from Double Negative are what make this exhibition so satisfying, as well as its confrontation of our relationship to objects that surround us, and the importance we assign to them. Perceptive and self-reflexive, Amie Siegel skillfully navigates the threshold between art and economics—between the human impulse to leave a mark, or to own it.

Amie Siegel: Double Negative is on view at Villa Stuck, Munich, through June 5, 2016. Amie Siegel: The Spear in the Stone is on view at Simon Preston Gallery, New York, from May 1 to June 19, 2016.