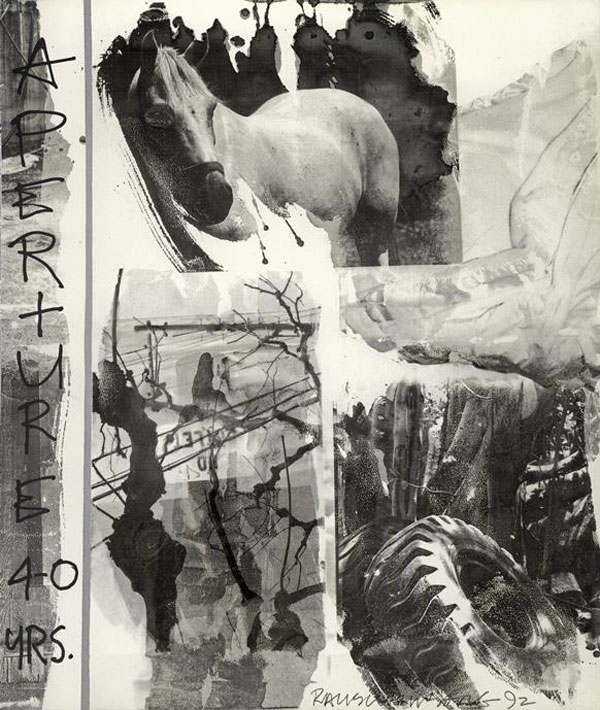

A Look Back at Aperture Magazine’s Fortieth Anniversary

The fall 1992 issue of Aperture magazine featured an original Robert Rauschenberg cover for the magazine’s fortieth anniversary. Inside, photographer Robert Adams interviewed Michael E. Hoffman (1942–2001), who built Aperture into a book publishing program, acted as publisher and editor of the magazine, and was the longtime director, from the 1960s through the 1990s. On the occasion of the launch of the Aperture Digital Archive, making every issue of Aperture magazine available online, appears this excerpt from that conversation, in which Hoffman speaks candidly about the early days with Minor White and Paul Strand, and about the development of Aperture.

Cover of Aperture Issue 129, with cover art by Robert Rauschenberg.

Robert Adams: In the first issue of the first volume of the magazine, in an opening statement about Aperture which is signed by [Minor] White and [Dorothea] Lange and all the rest, there is the following: “Aperture is intended to be a mature journal in which photographers can talk straight to each other.” In the early issues, there is in fact a striking and exciting willingness by photographers and writers to address fundamental issues in clear language, issues like “What are we doing?” and “What is it good for?” Do you have the sense that this directness is harder to come by now? And if so, why? And do you think there is any way around the increased academicization of photography?

Michael E. Hoffman: Think of Nancy Newhall. She was writing in a highly experiential, charged style. When you were near her and she was talking about photography and photographers, she vibrated. She was passionate. She was an intelligent, well-educated person who wrote beautifully.

I think at that time photography was life itself for people like her. They were in a process of discovery that was enormously exciting. There was no monetary support, there was no real outside interest. They were very much on their own.

What has happened today is that the academic side has overwhelmed the experiential side. A great many people have become interested in photography, but without bringing to it the qualities of engagement that force one to ask those primary questions. Instead, we get questions about style, and we get art-speak. . . . .

RA: Where and when did you first meet Minor White? And as you came to know him, what was it that most convinced you to shape your own life as you have—you’ve been working with Aperture since 1964. Was it his manner, or what he said, or his pictures, or all of this together?

MEH: I had been given a subscription to Aperture in 1957, when I was fifteen years old. At first, the magazine had no effect on me. Then, all of a sudden, one day I sat down to look at it, and three hours later I came back changed. I had never had such an experience of total immersion. It was the issue that Nancy Newhall had done on Edward Weston, at Weston’s death, called “The Flame of Recognition.”

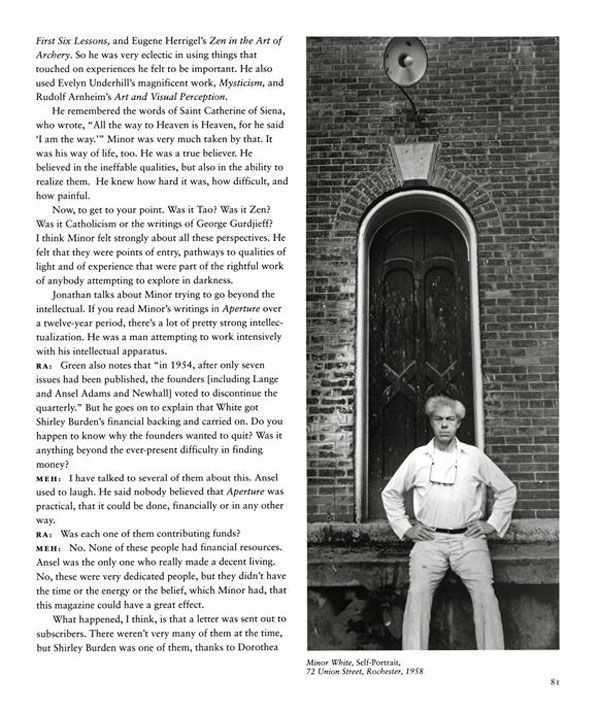

Pages from Issue 129 of Aperture.

RA: Had you yourself been photographing?

MEH: Yes. I had been taking pictures for about seven years. As a result of my Aperture subscription, I received a notice that Minor White was giving a workshop in Denver. I had just come back from college, and I said to myself, “This is something I could do.”

When I arrived at the workshop, I found it to be quite a bohemian setting. In the room there was a tall man with a beard, rather handsome, rather formidable—and I was sure that he had to be Minor White. To the right of the door there was another man with an open white shirt and some loose-fitting trousers. He had one leg up against the wall, and I think he was wearing sandals. I said to myself, “I wish this man would leave as soon as possible, because what the hell is he standing around here for? Why not get on with this important undertaking?” Of course, the man in the white shirt was Minor White.

I had never encountered a presence like his, somebody who was so unassuming, who had a relaxed, gracious manner, who was incredibly accepting of the people in the workshop, and who appeared to radiate a quality of light. Minor had a rather deep voice and a great presence. He gave us assignments that embarrassed me: we were to stand out on a street corner, for example, and let all the traffic and the people just go by. Just stand there. A lot of what we did, I only later came to understand, were the kinds of exercises that certain religious communities utilize to train people to become more aware, more present.

At one point we even went out to a garbage dump to start photographing. I thought, this is the limit, this is the end. I was going to give it up right there, and then things began to transform themselves before my eyes. I was astonished. We processed and printed every day, and then we had sessions so that we could look at what other people were doing. It was an intensification of what I had experienced with Weston’s “Flame of Recognition.” The search seemed somehow to give life real meaning, and Minor was both a guide and an ally.

RA: How did you then get to know White better?

MEH: Well, I tried to suggest to him that I could be helpful in the workshops that he was doing in the East. I was fishing, trying to find something. He was not very open to working with anybody. He was a very private person. In any event, he did agree to let me set up a workshop at the Millbrook School, a secondary boarding school I had attended. This was very successful, and so he agreed to give a workshop at St. Lawrence University. And then, in 1964, when I graduated, he invited me to Rochester to work with him personally, which I considered a great opportunity.

Aperture had gone out of existence in early 1964, and I said to Minor that I thought it should continue. And then I met Nancy Newhall, who was very supportive, although I suspect that Minor really didn’t want to see Aperture continue.

Pages from Issue 129 of Aperture.

RA: Why was that?

MEH: He felt that he had done everything that needed doing. Aperture‘s lifetime, then, was almost equal to the span of time during which Alfred Stieglitz’s Camera Work was published—Minor felt a very great connection with Stieglitz—and he thought Aperture had come to its natural end. He also was tired of the personal attacks, the lack of support, and the isolation. He had worked without any monetary compensation. He had devoted twelve years to the magazine, and had no money except what he earned as a part-time instructor. Minor eventually agreed, and Nancy and I decided we would do an issue on Weston, because the 1958 “Flame of Recognition” issue had reached only a few people. We decided to redo it simultaneously as a book and as the first new issue of the magazine, which had been dormant for almost a year. We had no money at all, and for a number of years I received no compensation. . . .

RA: Why don’t we talk for a little about Aperture the magazine as it has evolved since White gave up his guidance of it. In recent years, there has been a shift away from issues of mixed content to issues that focus on a particular theme, and some people—I think particularly photographers—have found that the results are often less interesting to them. They point out that the thematic issues sometimes seem to begin from an idea rather than from pictures in hand, and thus, perhaps inevitably, are not as exciting visually. Photographers also would suggest, I think, that these thematic issues have tended to discourage submissions of general portfolios. This may in turn be why the magazine doesn’t seem to have as many wonderful, anomalous shots, sometimes by unknown photographers, which made some of the earlier issues of the magazine so exciting. I am interested to know how you see the pros and cons of running a schedule of thematic issues, and interested to know if the practice is one that you think is valuable enough to continue.

MEH: Well, to begin with, I think the theme idea was a predominant mode in Minor’s approach to the issues in the early years. As Aperture evolved, and because of the editors—Carole Kismaric, Larry Frascella, Mark Holborn, Nan Richardson, Chuck Hagen, all of whom are very talented, as is our current group: Rebecca Busselle, Melissa Harris, and Andrew Wilkes—there was a desire to create a more coherent framework. I think it was a reaction to the portfolio approach, which seemed quite uncreative. There was no sense of a larger vision, a larger idea with which the pictures had to interrelate, by which they had to be challenged. I think that there was a desire among the editors to touch on ideas beyond those possible in a portfolio approach. In other words, larger ideas into which photography could focus and give a larger meaning, gain a larger meaning. . . .

RA: How does an issue originate? For example, does the idea usually come from in-house? And then what is the editorial process that leads to the choice of an issue’s theme?

MEH: We wrestle with that question all the time. We’ve been blessed over the years in having some very creative people involved with Aperture, all with very different views.

Chuck Hagen, for instance, wanted to do a show called “Drawing and Photography.” And he was deeply committed to the idea of doing this as an issue of the magazine as well. I think it was a marvelous exploration. It was really a chance to explore the medium in a broad variety of ways. Four issues before that, Melissa Harris did “The Body in Question.” In between, Andrew Wilkes edited “The Idealizing Vision,” on fashion photography; then there was the issue on German photography, and “Connoisseurs and Collections.” These were very diverse, equally valid approaches to photography and the magazine.

The hope is that in four issues we are able to cover enough ground and to include enough photographers to satisfy the need for people to be shown. But we really rely on the creative juices of the editors. We just did an issue called “Our Town,” which includes photographs by a broad variety of remarkable photographers, many of whom are not known, and marvelous texts by David Byrne, Richard Ford, Michele Wallace, Gary Indiana, John Waters, Marianne Wiggins, and others. We hope that this is a way to engage photographers, but also to achieve a broad cultural reach. We try to bring in a variety of forces of our time.

Click here to find the Aperture Digital Archive on the Aperture Foundation website.