On Robert Mapplethorpe's Polaroids

In 2001, art critic and philosopher Arthur C. Danto (d. 2013) wrote “Instant Gratification: Robert Mapplethorpe’s Polaroids 1970-1976” for Aperture magazine #163. In these early Polaroids, Mapplethorpe already begins to experiment with representations of his own body and those of others as well as erotic and bondage-based imagery. Danto recognizes this period as the moment when Mapplethorpe became a pure photographer rather than, as Danto calls it, a photographist, who uses photographs to achieve another artistic end. To coincide with the release of Aperture magazine #218, “Queer,” we republish an excerpt of Danto’s article on this brief but fascinating period in Mapplethorpe’s career. This excerpt first appeared in Issue 4 of the Aperture Photography App: click here to read more and download the app.

There is a useful distinction to be drawn between photographers, whose end products are photographs, and what I have termed photographists—artists who incorporate photographs into works that have a more complex artistic identity. It is not at all necessary that photographists be photographers in their own right—they can cut photographs out of newspapers or magazines, and combine them in montages or collages or installations. It is central to the meaning of certain of Christian Boltanski’s installations, to use one example, that the photographs he uses in them were found, and made by some anonymous journeyman photographer of persons whose actual identities have become unknown. Part of the aesthetics of post-Modernist art derives from the myriad roles played in daily life by vernacular photographs, or from qualities that certain vernacular photographs possess. The criteria of photographic art are not usually applicable to photographist works.

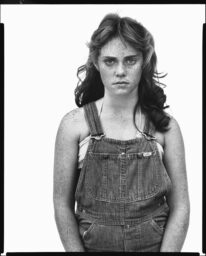

Robert Mapplethorpe’s career was unusual in that he began as a photographist, and evolved into a photographer, whose works are paradigms of high photographic art. These mature images were produced in a cultural atmosphere defined in part by photographism– an atmosphere in which swank and elegance were mistrusted, and artistic authenticity sough in the snapshot, in the blemishes, accidentalities, and disfigurements of uninflected picture-taking, felt to testify to a kind of honesty. There can be no doubt that Mapplethorpe’s portraits, for example, often reflected the glamour and celebrity of his subjects, which did not always sit well with his critics when the politics of anti-elitism found aesthetic reassurance in scruffiness and grunge. A photographer I knew, at the time working with pinhole cameras, wrote Mapplethorpe off as a pompier—a French pejorative connoting artifice and academicism. But even when Mapplethorpe was a photographist, working with Polaroids, the elements of his refined photographic style were already present in his work, as if he had a kind of perfect visual pitch, whatever means he used.

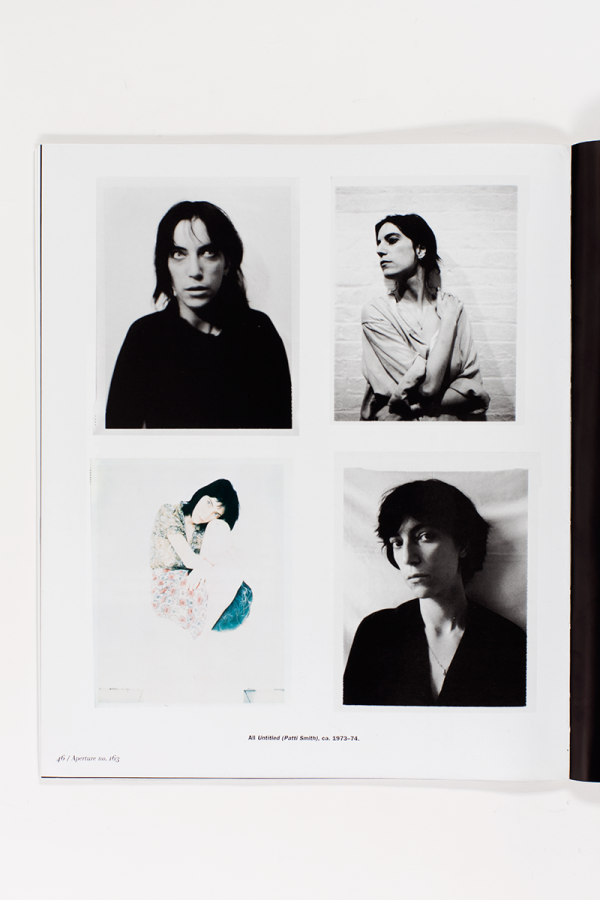

The transformation took place in the early 1970s, and its narrative can be told with reference to three mentors and four cameras. Mapplethorpe was already a photographist of sorts when, in 1970, he was given the use of a Polaroid camera by the artist Sandy Daley, herself a photographer and a fellow resident in the Chelsea Hotel. He was already a photographer when his patron and lover, the curator and connoisseur Sam Wagstaff, gave him a Hasselblad in 1976. He began to accept his identity as a photographer when John McKendry, Curator of Prints and Photographs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, gave him a Polaroid camera in 1971 as a Christmas gift. He declared a commitment to his calling in 1974 by buying himself a 4-by-5 Graflex with a Polaroid back. Initially, Mapplethorpe rejected the idea of a being a photographer at all, since he did not consider photography a legitimate art. By the time he acquired his Graflex, he not only endorsed its legitimacy, but the concept of photography permeated his vision.

Before meeting Daley, Mapplethorpe had shown no interest in photography whatsoever. Like his companion, Patti Smith, he was driven by extreme and, in terms of his youthful work, a somewhat unrealistic artistic ambition He had left Pratt, in part because he felt that the artistic philosophy of the New York School of painting, which continued to be taught there, had no relevance to being a young artist in the late 1960s. One can get a feeling for Mapplethorpe’s overall aesthetic at the time from the fetish necklaces he put together and sold, made of dice and death-heads, rabbit-feet and feathers, ribbons and claws. But he hoped to win success by means of his mixed-media collages, inspired by the work of Joseph Cornell and Marcel Duchamp, but using a symbolism derived from Roman Catholicism and black magic.

When he first used Daley’s Polaroid, he had begun to incorporate into his collages pictures of young men with attractive bodies, clipped out of magazines addressed primarily to a gay readership. His first thought was that he would use the camera to make his own pictures instead, which he considered more “honest somehow.” Either way, he was practicing photographism, since the pictures were used as collage material. But since the pictures they were to replace carried a sexual charge, his own photographs were also to have a sexual edge, though considerably sharper, as it turned out, than anything he had used before. The Polaroid process enabled him to show himself and others in situations he could photograph with impunity, since there was no need to send film out for development and printing. Mapplethorpe experimented sexually with his own body in front of the lens, to show the way he looked when he trussed his penis, or put it through rings, or mortified other parts of his flesh in accordance with his erotic curiosity. He photographed others in postures of bondage and sexual submission. These early self-images go well beyond what he might have encountered in the magazines sold behind counters in specialty shops in Times Square. But they also have a depth and power considerably in excess of the somewhat vapid images those magazines contained. It is not surprising that he should find his own photographs compelling, whatever his views on photography as such.

Arthur C. Danto was an American art critic and philosopher. He authored about 30 books, including Beyond the Brillo Box and After the End of Art. From 1984 to 2009 he was art critic for The Nation magazine and was a longtime philosophy professor at Columbia University.

Click here to learn more about the Aperture Magazine Digital Archive.