Are the Women Photographers of Magnum Getting “Close Enough”?

Gender inequality is particularly notorious in photography. An exhibition at ICP asks how far the storied agency can evolve in supporting new perspectives.

Bieke Depoorter, Agata, Paris, France, November 2, 2017

© the artist/Magnum Photos

A girl stands grinning down at the camera, her lilac hijab lifted by the wind like a sail. There is a playful, daring expression on her out-of-focus face, both knowing and open to all that is not known. Faces framed by windows look out from the building behind her: expectant, joyous, watchful, solidary. In this fantasy of an all-girl world—not segregated, but sought out—one might be as free as the foregrounded girl looks, blurred with her own becoming.

© the artist/Magnum Photos

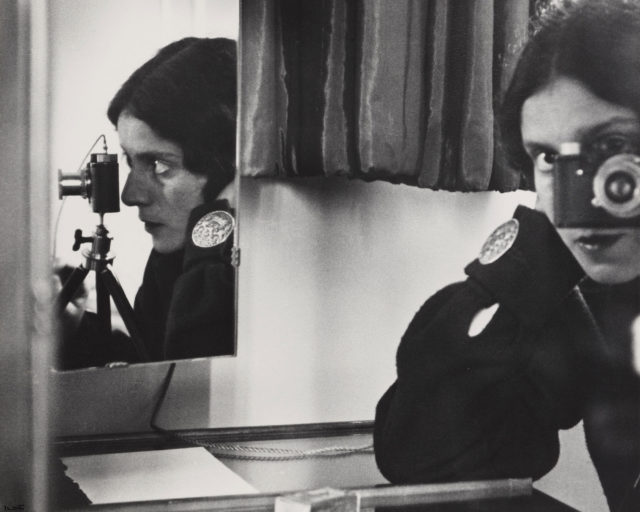

Sabiha Çimen’s 2018 image of a girl after her midterm exams appears in Close Enough: New Perspectives from 12 Women Photographers of Magnum at the International Center for Photography (ICP), and it stayed with me long after leaving the exhibition, which opened in September of this year, the photography cooperative’s seventy-fifth anniversary. Magnum was cofounded in 1947 by photographers Henri Cartier-Bresson, David “Chim” Seymour, George Rodger, and Robert Capa, who famously said, “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough.” Three quarters of a century later, the collective is still often associated with the masculine milieu of its origins.

As early as 1999, efforts to complicate this perception launched with Magna Brava: Magnum’s Women Photographers, a catalog and exhibition organized by Eve Arnold, the first woman to become a full Magnum member in 1957. It also included the work of Martine Franck, Susan Meiselas, Inge Morath, and Marilyn Silverstone. In 2018, Meiselas organized the group exhibition Magna Brava Ongoing to showcase the photography of a new generation of Magnum women.

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Others have recently called for institutional accountability against sexual harassment and abuse of power, or engaged critically with the collective’s history. Nadya Bair’s The Decisive Network: Magnum Photos and the Postwar Image Market (2020) makes a case for the collaborative network of women—sales agents, writers, editors, publishers, and spouses—essential to the success and impact of the predominantly male collective. Two lesser-known cofounders of Magnum were, in fact, women: Rita Vandivert, the first president and head of the New York office, and Maria Eisner, head of the Paris office.

“I wish for a time when we no longer need to have this conversation,” Bieke Depoorter has said; her work is featured in both Close Enough and Ongoing. The ongoingness of the issue can indeed madden, and there is much to be seen beyond the binary. We are not yet at Depoorter’s wished-for time—certainly not in the US, as celebrities tell us “time’s up” just before abortion protections are lifted, and we are left to self-manage our own human rights.

The twelve photographers “move and challenge the photography collective’s boundaries,” curator Charlotte Cotton writes in Close Enough’s introductory wall text, “deepening Magnum’s anchoring of the photographic quest to take account of human experience and survival. In uniquely personal ways, the contributing photographers negotiate gaining access, holding their bearings, and moving deeper in relation to human subjects and experiences.” Access, bearing, relation, and humanity being the language of reproductive rights as much as the photographic quest, I noted as I entered the show how my view might be colored by our particular national horrors, though the majority of images were taken outside the US. Close Enough manages to keep in focus a complex contemporary global web while individual works pulse with intimacy; that the photographers are women is both palpable and insignificant.

In the first room, scenes of girlhood stir. Çimen’s series Hafız (2017–20), the title meaning someone who has memorized the Koran, grows out of the artist’s drive to seek her younger self at a Turkish Koran school like the one she once attended. “I was struck by the girls who didn’t seem to care about how they looked in comparison to the so-called beauty standards set by social media,” Çimen writes, remarking on their “agency” and “resolute rebelliousness” in first person wall text (which accompanies each photographer’s work). Electric-pink smoke plumes before three girls all in black, powerful and partially obscured, like sorcerers. One girl with disarming eyes and cheeks pocked with acne scars brings fingers with chipped nail polish delicately to her forehead; another, flipping her eyelids inside-out with curled fingers, is vampiric in chiaroscuro.

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Nearby is Newsha Tavakolian’s film For the Sake of Calmness (2020), a strange and wonderful meditation on premenstrual syndrome and Iran’s highest volcanic peak. Tavakolian explains the analogy between the discomfiting porousness PMS creates between one’s body and the world, and the state of a country and a volcano—inactive, but always with the potential to erupt. Alessandra Sanguinetti’s images of her “long-term collaborators” Guille and Belinda, whom she’s photographed from ages nine to thirty-three, in rural Argentina, are time capsules full of personality, together a study in time’s passage.

Olivia Arthur’s installation of black-and-white photographs from 2016 to 2022 shows a world where gender can be fluid or queer, where sexuality, technology, intimacy or a lack thereof, and all the strangeness of having a body is taken head-on in a sculptural hodge-podge—what the artist calls a “mind map.” Myriam Boulos’s photographs taken between 2012 and 2022, including around Lebanon’s 2019 revolution, are a vivid punk-rock tapestry, a reclamation of “our streets and our bodies … and stories,” as Boulos puts it, where tongues meet in close-up, tattoos mingle with blood, and queer intimacy is luminous.

© the artist/Magnum Photos

© the artist/Magnum Photos

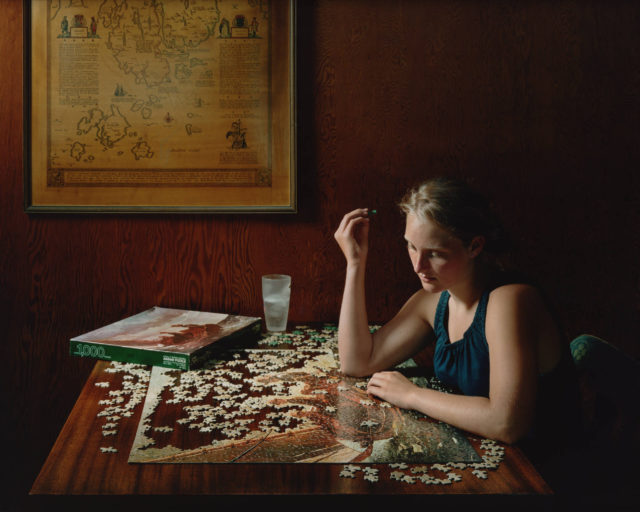

Carolyn Drake’s Knit Club (2012–20), a collaboration with Mississippi women to explore questions of “womanhood and motherhood” and possibility beyond “the control of the patriarchal system,” calls for close inspection. A wood-framed arrangement of images resembling a religious mantel hangs across from Arthur’s installation. It is a beautiful world these women create, but not one without darkness. A woman with a papier-mâché face holds a turned-away child; a haunting figure in a pink nightie and eagle head brings to mind a Hafız girl wearing a gorilla mask, grasping a friend’s chin, playing with threat.

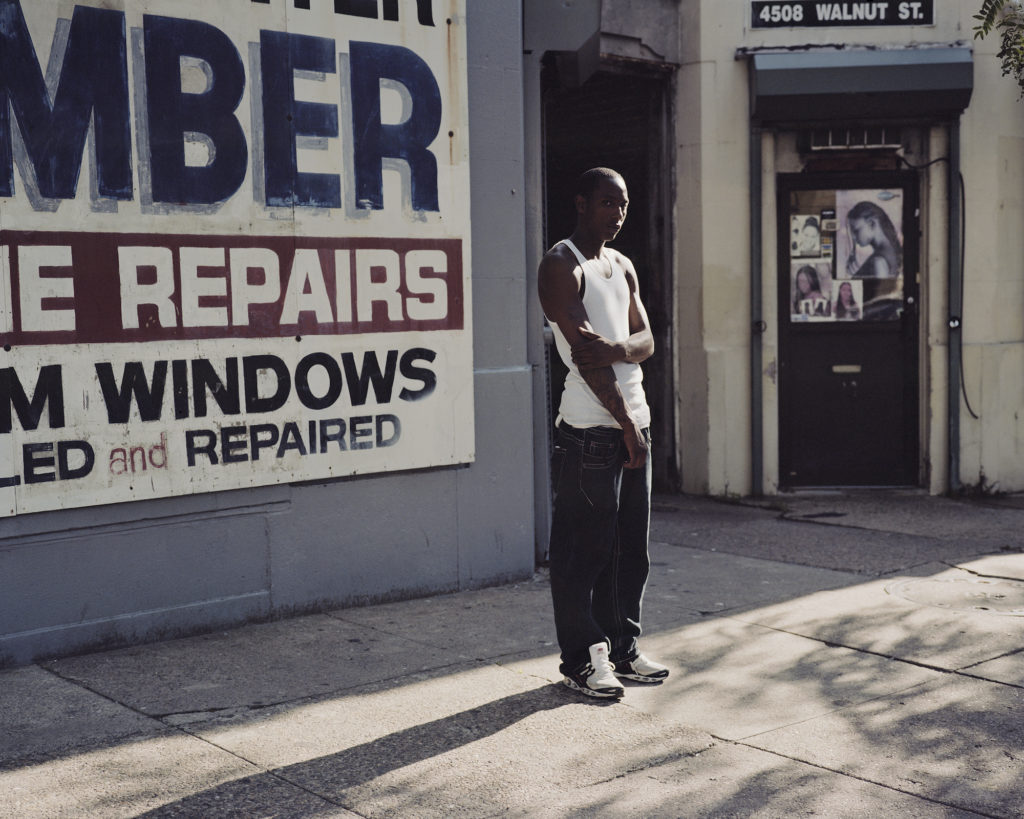

Hannah Price trains her lens on the men of Philadelphia in her series The City of Brotherly Love (2009–12). “As I commuted to and from work, up to five times a day I’d be thrown off guard by a man catcalling in my direction,” Price writes. “The fact that I responded at all was a surprise to them, and I’d turn the conversation away from attraction and ask if I could photograph them.” Perhaps it is surprise that renders the faces of these men notably open. Some seem shy or defensive, others humorous or inquisitive, as if trying to assert something but aware of a shifted dynamic; now they are seen. And to some, perhaps, it is an interesting proposition.

© the artist

As I moved upstairs, I considered what subtle play with power and the lens can reveal. Over the last near decade, ICP has largely worked with curators in residence rather than staffing curators. The prolific writer and curator Charlotte Cotton is one such resident, as is Cynthia Young, who curated the other show now on view: a detailed account of Robert Capa’s 1938 Spanish Civil War photobook, Death in the Making. (ICP was originally founded by Capa’s brother, Magnum member Cornell Capa, in 1974; Mark Lubell, formerly the New York head of Magnum, was director from 2013–21.)

Close Enough manages to keep in focus a complex contemporary global web while individual works pulse with intimacy; that the photographers are women is both palpable and insignificant.

As Magnum has opened itself over the years to a wider range of photography, the number of women in its roster has increased. Yet, today, of the ninety-eight members, only sixteen are women—to say nothing of race. (Two former women members have resigned; others have not proceeded through the stages of what the collective calls a “rigorous process” to attain full membership.) Price, whose Brotherly Love series is on view at ICP, is in fact no longer with Magnum. That Close Enough includes the work of exciting, young, international photographers may seem a return to ICP’s tradition of innovative and globally diverse triennials. Or, yet another Magnum show may signal a lack of vision, or a bid for positive PR for the collective.

Gender inequality is particularly notorious in photography; it also pervades the world. The premise of Close Enough: New Perspectives from 12 Women Photographers of Magnum and the title’s accidental implication—here, Capa’s challenge that photographers get “close enough” sounds more like shrugged-off defeat—tells of how far not only Magnum but many storied institutions are from practicing what they preach in support of “new perspectives.”

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Upstairs, in a darkly lit space, Bieke Depoorter and Cristina de Middel share a wall, their images, which both deal with sex work, displayed back-to-back. Depoorter’s photos, videos, and letters document her multiyear collaboration with Agata Kay, whose presence is captivating. Depoorter’s moving images—of Kay dancing, alone and with a client; of the two women singing together on a roadside—hold heat. In a 2019 missive to her collaborator, Depoorter interrogates the boundaries of their relationship, noting her confusion and admitting, in another letter, to not selecting the images “where I seem drunk . . . where we kissed . . . I performed too.” Agata writes, “Maybe you look for yourself while looking for me.”

The ninety-nine photographs and testimonials of men and one woman who responded to de Middel’s open call for clients of sex workers—from Rio de Janeiro, Havana, Mexico City, Paris, Bangkok, Los Angeles, Lagos, Kabul, Amsterdam, and Mumbai, between 2015 and 2022—overwhelm the wall with their sheer volume and the power of their exposure. In her own text, de Middel describes her aims as a witness, but also her experience as a woman and survivor of sexual abuse.

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Displayed on either hallway, stretching out like balconies over the main exhibition floor, are photos by Nanna Heitmann and Lua Ribeira. Heitmann traces the escalating Russian invasion of Ukraine, centering Russian television propaganda and witnessing the last public protests in Moscow in February 2022; the vacant blue eye of one Russian policeman pierces, visible through a hole in his protective head gear. Ribeira’s stark, sun-soaked portraits picture young people in the trap and drill music scene “across the Spanish territory,” which she herself is close to and believes is “resonating globally for a reason.”

© the artist/Magnum Photos

Finally, Meiselas’s A Room of Their Own (2015–16) fills ICP’s two-story wall near windows overlooking Essex Street. It is a collaborative work comprised of photographs and video from shelters, as well as testimonies and artwork by survivors of domestic abuse in the UK. The odd, inventive arrangement of images throughout the show—some on folding screens or accordions, some displayed architecturally, and including that two-story wall—must speak to the particular ways the artists want their work seen. However, it could feel a bit needlessly slick, even obscuring, to have to angle for a view; perhaps that is in part the point.

What clearly unites Close Enough is a sense of intimacy between photographer and subject so strong that the distinction doesn’t hold. There is an investment in understanding the other—imperfectly, messily—through the act of seeing, and a thrust to know the self through this same process. It is exhilarating to behold this bravery and purpose work themselves through very different lenses.

While institutions have learned what to say, how to champion diversity for their own public image without undertaking the actual demands of structural change, there are also real people working for real change from within and beyond these same institutions—often enough women, gender nonconforming people, and people of color. And despite the structural issues, many who are celebrated as examples of institutional progress do produce work that deserves recognition. How we may wish to no longer have these same conversations!

“I feel that the focus should be the links between our work, more than us being women,” Depoorter said of Ongoing. “I think it’s obvious that it’s about much more than that in the show.” I left Close Enough thinking the same. Like in Çimen’s photographs, an all-girl world might be sought—not to prove a point for someone else’s benefit or because that is all there is to see, but because of what we may discover there.

Close Enough: New Perspectives from 12 Women Photographers of Magnum is on view at the International Center of Photography, New York, through January 9, 2023.