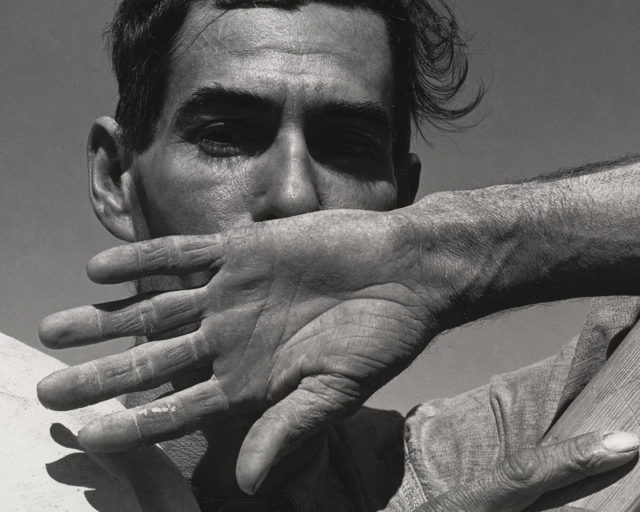

Bruce Yonemoto, Untitled (NSEW 4), 2007, from the series Untitled (NSEW)

Courtesy the artist

On September 4, 1949, shortly after closing a benefit concert for the Civil Rights Congress near the upstate New York town of Peekskill, the singer and activist Paul Robeson was hustled into a car and told to lie on the floor, to protect himself against an assassination attempt. Anti-Communist rioters and Ku Klux Klan sympathizers had ambushed the departing audience, hurling rocks the size of tennis balls. Pete Seeger, who opened for Robeson with a new protest song called “If I Had a Hammer,” was in a car with his wife and two small children. The police stood by as a riot engulfed the country roads; the windows of Seeger’s car were shattered, and more than one hundred and forty people were injured. At home, Seeger washed the glass out of his children’s hair. In the 1950s, Robeson and Seeger were accused of Communism and blacklisted. “I remember a high-up official in the Communist Party,” Seeger recalled of the Communist writer V. J. Jerome. “He said, ‘Pete, don’t you realize this is the beginning of Fascism taking over in America? You know they have concentration camps for people like us already set up?’”

Seeger and Lee Hays’s song “If I Had a Hammer,” the rousing folk standard once seen as taboo socialist agitprop, was on the mind of Steven Evans, the executive director of FotoFest in Houston, when he and the curators Amy Sadao and Max Fields put together the 2022 edition of the organization’s biennial. Spanning photography, video, and lens-based art, and subjects with overlapping themes of social justice and civil rights—including the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II, the 1954 US-backed coup in Guatemala, the enduring surveillance state in Washington, DC, and the extraordinary rise of photo-sharing platforms—If I Had a Hammer, titled after the song and installed in Houston’s Silver Street Studios, exemplifies the hand-wringing mode of numerous exhibitions mounted in the wake of the Trump presidency and the COVID-19 pandemic. “If I had a hammer,” the lyrics go, “I’d hammer out a warning.” At FotoFest, there’s both sound and fury, and an urgent sense that we must interrogate history if we are to survive the present.

Courtesy FotoFest

The history lessons are robust. If I Had a Hammer opens with an enormous, wallpaper-style print of a Dorothea Lange photograph. Taken in Oakland in March 1942, three months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, it portrays a shop owned by a Japanese American who would later be forcibly relocated by the US military to an incarceration camp. “I AM AN AMERICAN,” a sign reads in the shop’s windows. (The majority of incarcerated Japanese Americans were born in the US and therefore citizens by birth.) After working for the Farm Security Administration to photograph the crisis of migrant workers during the Depression—Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California (1936) being her emblem of the era—Lange took up another government assignment when the US entered World War II. She documented Japanese American families preparing to leave Oakland and San Francisco, and, with instructions from the US War Relocation Authority not to show barbed wire and other unsettling details, she made photographs inside Manzanar, a prison camp in the California desert.

At FotoFest, there’s both sound and fury, and an urgent sense that we must interrogate history if we are to survive the present.

Unlike her images from the 1930s, which were published widely at the time, Lange’s work for the WRA was not made public during the war. In 1942, she was discharged by the agency. Her photographs were accessioned by the National Archives in 1946 and digitized fifty years later; today they’re available to download from the National Archives Catalog. “I went through an experience I’ll never forget when I was working on it and learned a lot,” she wrote in 1943, in a letter to Ansel Adams, who photographed at Manzanar after Lange’s departure, “even if I accomplished nothing.” Yet, as If I Had a Hammer illustrates, Lange’s accomplishment is vivid on its own—the exhibition includes a generous number of new prints made from Library of Congress scans—and accrues dimension when viewed in conversation with Toyo Miyatake’s contrasting account of Manzanar.

Courtesy Toyo Miyatake Studio

Miyatake, who was born in Japan in 1895 and ran a flourishing portrait studio in Los Angeles before the war, cleverly slipped parts into the camp to build a camera, which was banned. He made clandestine photographs until he was found out. Ralph Merritt, the camp’s director, later permitted Miyatake to set up frames himself, but the shutter release had to be pulled by a white person. (Eventually, this rule was dropped.) Miyatake’s photographs are both sober and shocking. One of the most famous, from 1944, portrays three boys with tragic expressions alongside a barbed wire fence, their searching looks conveying their state of anguished captivity. In the background looms a guard tower and snowcapped mountains. Did this scene really occur in the United States, home of the “free”? Or is this the most American of scenes, a visual metaphor for the paradox that “freedom” is balanced atop the pillars of incarceration, forced labor, and terror against the unfree?

Courtesy the artist

Courtesy the artist

Evans notes that the dialogue between Lange and Miyatake forms the “emotional center” of the Biennial. Certainly, in light of the devastating child-separation policies at the Southern US border and the recent construction of tent camps for migrants sent to New York, Lange and Miyatake’s images feel as frighteningly relevant as ever. Between the presentation of their works, on opposite ends of an immense hallway, are numerous photographic statements that spin out themes of freedom, resistance, and political determination at varying frequencies. Bruce Yonemoto’s stately portrait series Untitled (NSEW) (2007) reimagines soldiers who served in the Civil War, with models of Asian descent posing in the style of nineteenth-century cartes de visite and dressed in costume uniforms originally used in D. W. Griffith’s notorious film Birth of a Nation. Mike Osborne’s Federal Triangle (2019–ongoing) profiles government institutions and street scenes in Washington, DC, with the sinister eye of a film-noir auteur. Keisha Scarville installed fabric prints that float from the ceiling and summon the darkness of the American landscape from the perspective of a fleeting Black female presence, blurring, as she says, “the specificity between the body and the terrain.”

Courtesy the artist and Higher Pictures Generation, New York

Courtesy FotoFest

Courtesy the artist

Several of the most intriguing projects in If I Had a Hammer concern archives and preexisting images as the raw material for introspection. Ryan Patrick Krueger scoured eBay using search terms such as gay interest and male affection to assemble large collages that interrogate the queer vernacular imagery in the decades before Stonewall. Working in Mongolia, a global capital of mining for elements essential to the production of digital devices, David Kelley hired local actors and posed them for portraits in the style of commercial stock photography, then uploaded the final versions to iStock, adding search keywords in an ironic gesture of recirculation.

Fred Schmidt-Arenales, an artist in residence at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, tells a story about the 1954 coup in Guatemala, a political disaster engineered in part by the CIA and the United Fruit Company. Schmidt-Arenales’s grandfather was a correspondent in Guatemala for the New York Times and later a State Department diplomat. For his project The New York Times on Guatemala (2022), Schmidt-Arenales scanned articles from the newspaper that covered the coup and redacted certain texts and images. The thirty-nine framed prints, organized chronologically according to the article datelines, become an homage to Sarah Charlesworth’s Modern History series from the late 1970s. Schmidt-Arenales also invited four other artists, David Ramírez Cotón, Daniel Hernández-Salazar, Camila Juárez, and Jorge de Léon, to make their own responses to his grandfather’s 1950s-era photographs. Among these, de Léon’s two-screen video, Untitled (image 4 and 17) (2022), of nine people (including a wry young boy) on a steep city street, clapping endlessly, is a charming and absurd vision—and one of the highlights of the exhibition.

Courtesy the artists

Courtesy the artist

The FotoFest Biennial, which extends across Houston in numerous galleries and museums, also includes a reinstallation of the 2020 edition, African Cosmologies, which was on view for only a few weeks before the pandemic forced institutions to close. The opportunity to see both biennials simultaneously provides a rare and kaleidoscopic platform for contemporary photography. Contributing to this is the experience of encountering emerging talent in the exhibition Ten by Ten, featuring artists selected from FotoFest’s portfolio review; Alejandro González, Will Harris, and C. Rose Smith make especially strong impressions.

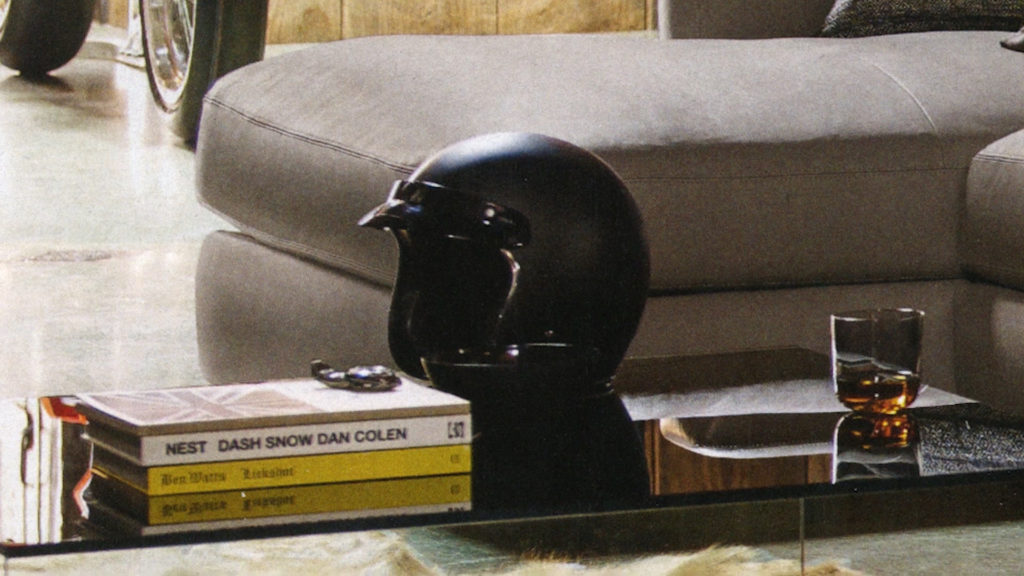

The complex, finely calibrated messages of If I Had a Hammer provoke difficult questions about what art can actually do for society beyond illustration. Against the edifice of power and corruption, would an artwork alter the course of history? Would a biennial change the mind of a staunch partisan? Amid the noise of political anxiety, Liz Rodda’s cryptic piece Turn Your Face Toward the Sun (2016), assembled from found video and audio, offers a critique of willful optimism. As a camera pans across magazine images of stilettos, parquet floors, handsome furniture, and well-placed art books, a young woman whispers what she calls “positives affirmations.” The sound is muffled, yet the clichés resound as commands. “Move on, it’s just a chapter in the past,” she says. “Don’t close the book, just turn the page.”

If I Had a Hammer, the FotoFest Biennial 2022, is on view at the Silver Street Studios and Winter Street Studios in Houston through November 6, 2022.