At Home with the Fotohof

Fotohof. Zhe Cehen installation view and exterior section.

Photography galleries no longer survive simply as rooms with framed pictures on the walls. Many are yet to assimilate this premise, with predictable—and often lamentable—results. A pioneering reinvention of one venue is the Fotohof that opened in Salzburg, Austria, in February 2012. It is an airy and alterable space that the innovative designers transparadiso describe as “open transparent architecture.” The Fotohof tempts passersby with an outward-facing panel of plasma screens of with scrolling images, beyond which they can see a changing spread of indoor exhibitions and activities integrating the social, educational, and cultural.

Even the name is suggestive: originally, a hof was a farmstead or a courtyard; today the term is most often applied to an inn or a pub. Somewhere homely, in short, and indeed the gallery was formerly located in the picturesque Nonntal district at the foot of a mountain. The new Fotohof retains an emphasis on warmth and welcomeness, without the chintzy associations. In the words of Fotohof photographer and collective member Kurt Kaindl, the new building was planned from scratch “by all of us working together with the architecture firm transparadiso. We all agreed on a lot of glass so you can look from outside into every single room (except the bathroom) and allow those inside to see what’s going on in the library, or the offices, or outdoors on the street.” As an example, the library’s more than ten thousand core volumes, a remarkable resource, are available for both research purposes and for presentation in exhibitions alongside photographic prints, affording an insight into how content alters with context.

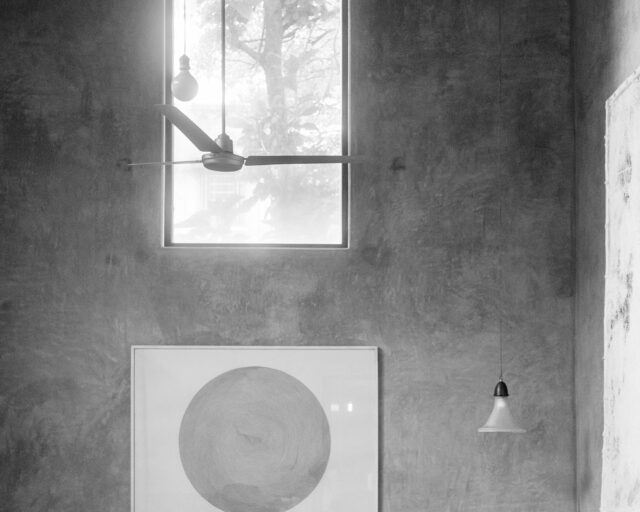

Fotohof. Installation view.

This is the Fotohof ‘s fourth home in forty years. The organization was created and is run by a remarkably consistent photographic collective of around twenty members. The first gallery was in someone’s living room; the second was a couple of tiny rooms in a shared flat. What persists is a group of photographers who continually reach out to new audiences without being impelled by either commercialism or self-promotion. The new space may be more formal, but the motivation remains to present fine-art photography at the highest level. The institutionalization resides in the Fotohof’s newest aspects, which are paradoxically also the most traditional: in the library; the pedagogical remit; and the homage to Inge Morath (whose work is on regular display in a number of curated exhibitions). The innovation lies in the continual (re)discovery of new talent, from home and abroad; the flexible spaces in which photography can be shown; and in extending the book library to the new Artothek print-lending library. Visitors are encouraged to rent framed prints they like (for €4 per month and for up to one year) and so become accustomed to living with fine original artwork on their walls—whether or not they finally decide to purchase them, and with no pressure to do so.

The combination of high artistic standards and collective commitment is evidenced by the new premises. The building is sited in the working-class district of Lehen, where dilapidated 1960s-era apartment blocks were demolished and rebuilt as low-rises flanking a new square. Named Inge Morath Platz, after the seminal photographer who was an early member of Magnum Photos and wife of American playwright Arthur Miller, it is intended as at once an homage and a celebration. The name is reinforced by a new, annual Inge Morath award for female photographers under the age of thirty. Throughout the summer, the Fotohof screened work by recent finalists—Olivia Arthur, Lurdes R. Basoli, Zhe Chen, and Emily Schiffer—alongside Morath’s own early work from Spain.

Fotohof. Main gallery

Fotohof. Dirk Braeckman installation view.

Across and around the square original residents have been re-housed in ecologically sensitive buildings. All were invited to the opening, where they were greeted by the mayor of Salzburg, the Minister for Education, Arts and Culture, local city councilors, and Belgian photographer Dirk Braeckman, who spoke with Jeffrey Ladd about his work, which inaugurated the new galleries. To mark the festive occasion, new work by contemporary Austrian artists was presented on-screen and Fotohof staff provided tours of the different areas of the gallery.

Such a high-profile launch demonstrates the commitment, at municipal and federal level, to the project, which necessitated ten years of discussion and planning among officials, photography practitioners, and activists. The importance of the state in making this happen can hardly be over-estimated. Under a scheme to support cultural and social institutions the City of Salzburg negotiated a fifty-percent rent reduction on commercial rates with the property developers, adding a grant of €600,000 for furniture and equipment. Overall the Ministry of Culture now provides fifty percent of the Fotohof’s operating costs, while the city and county of Salzburg each provide an additional twenty-five percent. According to Fotohof member Kurt Kaindl: “We have remained a non-profit organization since we started in 1981, and we are not employers. All those who work on our projects are remunerated according to the tasks they do. Roughly fifteen people who work in the gallery on a regular basis are on the executive committee, deciding on exhibitions, book projects, and the overall strategy of the gallery.”

Fotohof. Bookstore.

For government at both national and local level to back such a scheme is exceptional in modern Europe, even in a country whose contribution to the field of photography is as important as Austria’s. For the past decade, governments across Europe have increasingly assumed that the private sector should provide funding for culture, whether it actually does or not. Culture is subsumed within a changing grab-bag of ministerial portfolios, including leisure, tourism, women, media, or sport: at best it is an optional add-on. Within Austria, the Fotohof is regarded as a trailblazer, the first element in a cultural hub that will include the new Galerie der Stadt Salzburg; the Literaturhaus; the GalerieEboran, and the City of Salzburg Library.

Andrew Phelps, an American photographer and Fotohof collective member since the early 1990s, embeds the national enterprise within a wider tradition. “The Fotohof was founded a decade after the British Photographers’ Gallery. Both London and Cardiff [where Ffotogallery was directed by American Bill Messer] were early models. And our first exhibitions included several that travelled from there.” While we can all do with state support to make things happen, the arts are everywhere at home.

Fotohof. Exterior view.