At the Venice Biennale, a Surreal and Intimate Showing for Photography

From Yuki Kihara’s reinterpretation of Gauguin to Elle Pérez’s “configurations,” the international exhibition features a range of perspectives on image making.

Installation view of Yuki Kihara, Paradise Camp, 2020. Photograph by Gus Powell

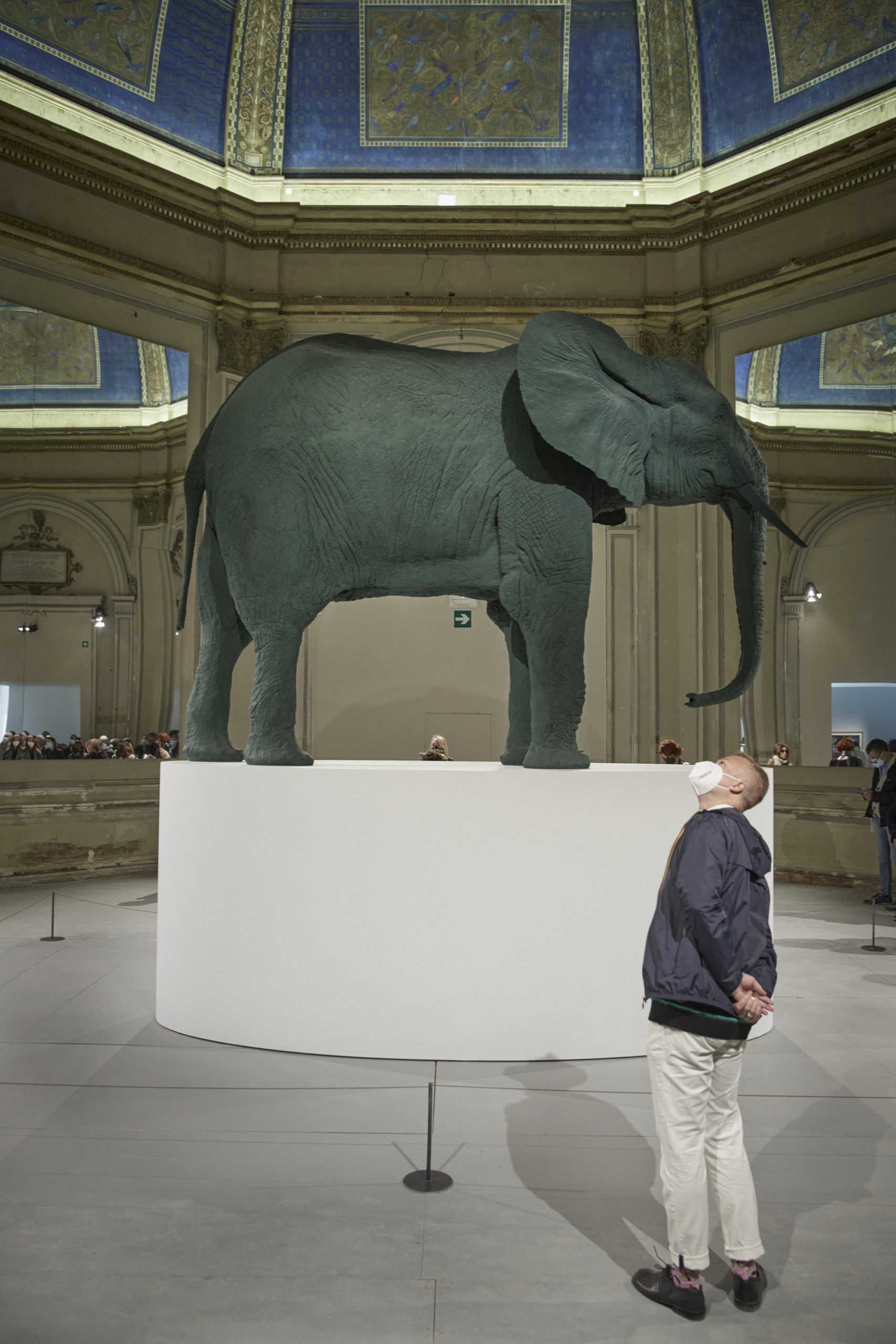

The 2022 Venice Biennale opens, in the Giardini, with an image of a green elephant: life-size, atop a white pedestal, radiating in the magnificence of its unnatural being. A surreal apparition, it recalls certain scenes shot by Paolo Sorrentino, in which a silent gorilla may pervade, with enigmatic mystery, the carefree tranquility of the Vatican gardens. Time stands still and the viewer cannot help but wonder: Why? An answer does not necessarily exist. The green elephant is a 1987 work by Katharina Fritsch, winner of this year’s Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement award, along with Cecilia Vicuña. Standing at the beginning of the international exhibition, titled The Milk of Dreams and curated by Cecilia Alemani, director of High Line Art in New York, the sculpture is a sort of declaration of intent: the dream will be the main dimension of the art presented in this Biennale.

Another animal-symbol present in the Biennale is the giraffe. In fact, there are eight white giraffes that drag a large anatomical model of the male reproductive system on wheels, to which are affixed tags bearing the names of illnesses that can afflict individual body parts. This work by German artist Raphaela Vogel, titled Ability and Necessity (2022), resembles an ancient Roman triumphal procession and positions the male organ as the definitive war trophy for the patriarchy. The Milk of Dreams is a feminist exhibition not only in terms of numbers (it is very difficult to recall a male artist among the 213 participants) but also, and readily, in its contents. The feminist and surrealist imprint will be why this Biennale will make history, no matter what you think of it.

If instead observed from the perspective of photography, which occupies a marginal presence at the Venice Biennale, Alemani’s exhibition does not seem capable of being a watershed moment. We see no true shake-up regarding the medium’s reflections or evolutions, only excellent choices that enrich the exhibition’s collective effect, which is another of its great virtues.

Courtesy the artist and La Biennale di Venezia

Let us begin our examination with the well-deserved tribute to Nan Goldin, who is exhibiting for the first time in the Venice Biennale. The work she presents is not a series of photographs but a sixteen-minute video, Sirens (2019–20), that is dedicated to Donyale Luna, considered the first top Black model and who died from an overdose in 1979. The video, a collage of clips taken from works by Kenneth Anger, Henri-Georges Clouzot, Federico Fellini, and Lynne Ramsay, as well as screen tests by Andy Warhol, attempts to convey the glamourous atmosphere associated with drug use. Its title refers to mythological characters who are both seductive and lethal.

Louise Lawler is also having her Biennale debut, and Alemani has entrusted her with the mezzanine level of the central pavilion in the Giardini. Titled No Exit (2022), this wall installation surrounds an area where performers will circulate, through July 3, for a work by Alexandra Pirici. Lawler uses Hair (adjusted to fit) (2005/2019/2021), a vinyl-printed image that completely covers the walls of the room, as an abstract backdrop for ten large-scale photographs. These capture the works of Donald Judd as exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 2020, but when the gallery’s lights were off. Lawler often questions art history by attempting to strip works by (male) grand masters of contemporary art of their sacred nature in their exhibition contexts, whether museums or private dwellings. Here, she hunts down works by Judd in the darkness, where the purity of their minimalism is more vulnerable and the luminosity of their conceptual backing is obscured. Another paradox is the relationship between the intrinsic cleanliness of the works portrayed and the chaos of their backdrop, which depicts a Maurizio Cattelan sculpture of a taxidermic cat standing on the back of a dog that faces an Andy Warhol self-portrait.

Not far off, again in the spaces of the Giardini, are works by Sheree Hovsepian, an Iranian-born American artist. Installed on a wall, her assemblages incorporate black-and-white analog prints and various materials such as wood, nylon, ceramics, twine, and nails. Small photographs show portions of the body of the artist or of her sister, her body double. At times, back, torso, and arms become figurative epicenters of sensual, abstract, geometric compositions, or what one might call new bodies born from the artist’s imagination, which has a surrealist and somewhat retro taste. The juxtaposition of these compositions, installed in severe walnut frames, recalls the material and forms of the central pavilion’s window by Carlo Scarpa that is formed by two intersecting circles. It probably constitutes the most successful burst of poetry in this Biennale.

Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia

Among the photographers invited to the Biennale, Aneta Grzeszykowska leaves the most unsettling impression. Her series Mama (2018) consists of twenty medium-sized photographs, in color and in black and white, that portray the artist’s daughter while she interacts with a silicone doll that has Grzeszykowska’s features. In certain close-up shots—of the young girl covering her mother’s eyes with her hands, sweetly resting her chin on her shoulder, or painting her face red—it is the unnatural gaze of the doll that throws the viewer off balance. The deception is revealed when the doll is shown without legs. The relationship between mother and daughter is reversed, and it is the latter who looks after the simulacrum of the former. And the poetics typical of Surrealism demonstrate, in cruel fashion, the crisis of the maternal institution.

Courtesy the artist and 47 Canal, New York

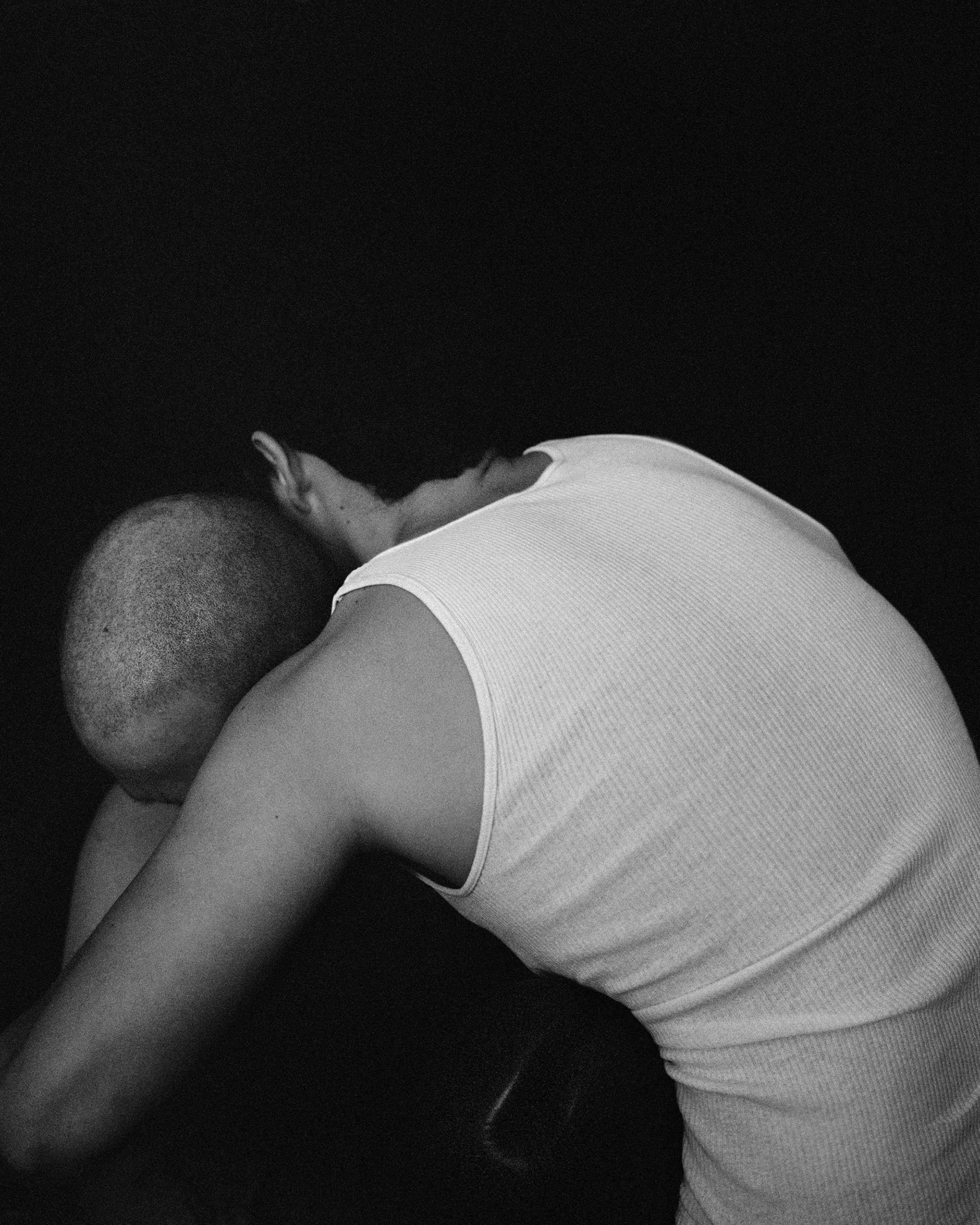

The youngest photographers chosen by Alemani are the American artist Elle Pérez and the Polish artist Joanna Piotrowska (the only photographer shown in all the Corderie dell’Arsenale). What the two have in common, in addition to the use of black-and-white images, is a reflection on bodies that touch each other and interact. Pérez is an artist already featured in the Whitney Biennial. In Venice they present their “configurations,” the subject of which is the so-called “chinch,” the part of martial arts combat in which the contenders are in a standing contact position, using holds on the upper body. For Piotrowska, the contact of bodies is what takes place in domestic contexts, within the walls of the home where, far from the gaze of strangers, gestures of violence as much as those of care are consummated. Some of these pictures appeared in the book Stable Vices (2021). The image of physical interaction, for both photographers, becomes a metaphor for human relationships, grounds where virtue and subjugation, affection and hatred, can coexist, alternate, or oppose each other.

In all these photographs, we find echoes of the poetics of artists with work at the center of the Giardini pavilion, in one of five “time capsules,” as Alemani calls the mini thematic exhibitions that present artists who are no longer living, many of them lesser known. Titled The Witch’s Cradle, it includes works by female photographers such as Eileen Agar, Gertrud Arndt, Claude Cahun, Florence Henri, and Ida Kar.

The image of physical interaction, for both Pérez and Piotrowska, becomes a metaphor for human relationships, grounds where virtue and subjugation, affection and hatred, can coexist.

Among the eighty national pavilions, those representing Canada, Israel, New Zealand, and South Africa focus predominantly on photography. Stan Douglas’s exhibition 2011 ≠ 1848 is displayed at two venues, the Magazzini del Sale no. 5 and the Canada pavilion in the Giardini. In the former, Douglas presents a virtuoso two-channel video, in which viewers witness a long-distance dialogue between two rappers from London and one from Cairo; this is probably the part of the exhibition that will make the pavilion most memorable. In the Giardini, the Canadian artist shows four large-scale prints dedicated to various uprisings that occurred in 2011 in Tunisia, Vancouver, London, and New York. These are digital photomontages of scenes made in studios with actors, embedded in reconstructions of urban settings made with computer graphics. From a few yards away, the realistic effect, obtained through an impressive array of technologies, is convincing. But close examination reveals that something is not completely natural. Douglas calls his photographs “hybrid-documentaries.” The photos are fake, but the news is real. The result brings to mind the history-making function of overembellished paintings of coronations or battles in open fields, when photography did not yet exist.

In the Israeli pavilion we enter Queendom by Ilit Azoulay, who intended to create a space governed by the logic of art based on female and cultural emancipation. The project takes as its point of departure an almost forgotten archive of photographs of Medieval metal vases from the Islamic world. Its collector, David Storm Rice, was an 18th-century Austrian Jewish British art historian who donated it to the L. A. Mayer Museum for Islamic Art in Jerusalem, thus preserving it in one of the most important museums in the world. Azoulay has scanned, cut out, and modified hundreds of these photographs, recomposing them digitally in seven large-scale prints. They are new artifacts of a rewritten history whose protagonists are no longer male warriors and kings but women. Azoulay’s idea, at heart, is to collapse into new images a visual history that has been forgotten and scattered all around the world, reflecting a utopian desire to recompose something that has been shattered. Perhaps her works are a type of kintsugi, the traditional Japanese art of repairing broken objects with gold.

The New Zealand pavilion is devoted to Yuki Kihara, whose exhibition is titled Paradise Camp. The hub of this project, which also includes a video and installations of archives, is a series of twelve photographic images that reinterpret paintings of Tahiti by Paul Gauguin. These are actual works d’apres, for which the models belong to the fa’afafine community, Sāmoa’s third gender. Kihara, who is fa’afafine, was inspired by a 1992 article by Ngahuia Te Awekotuku, a Māori academic and lesbian activist, that notes how Gauguin endowed his models with androgynous and exotic features due to his fascination (as the painter described in his journal) for māhū, the Tahitian equivalent of the fa’afafine concept. Kihara gives us a version of Gauguin’s paradise in technicolor or, in keeping with the title of the pavilion, a camp version.

Viewing the 2022 Venice Biennale through photography, one cannot help but conclude with Roger Ballen’s series The Theatre of Apparitions (2016) in the South Africa pavilion at the Arsenale. Ten medium-sized lightboxes present an equal number of black-and-white photographs of drawings that the artist made with various techniques on the windows of a building in Johannesburg. Disturbing and childish apparitions, the subjects are typical of this South African photographer’s dark imagination. The gallery contains more than nightmares: premonitory dreams imbued with a sense of mystery. As I traversed the small room, Ballen’s words, published in Photo No-Nos, a book edited by Jason Fulford, came to mind: “It is clear to me that at this historical moment, a great percentage of contemporary artists and photographers are not interested in making the transition from the exploring media-driven slogans to coming to terms with the enigmatic, mysterious boundaries of our short lives on this planet.”

Translated from the Italian by Marguerite Shore.

The 59th Venice Biennale, including The Milk of Dreams, is on view through November 27, 2022.