At Mariane Ibrahim's New Chicago Gallery, an Otherworldly Portrait Series

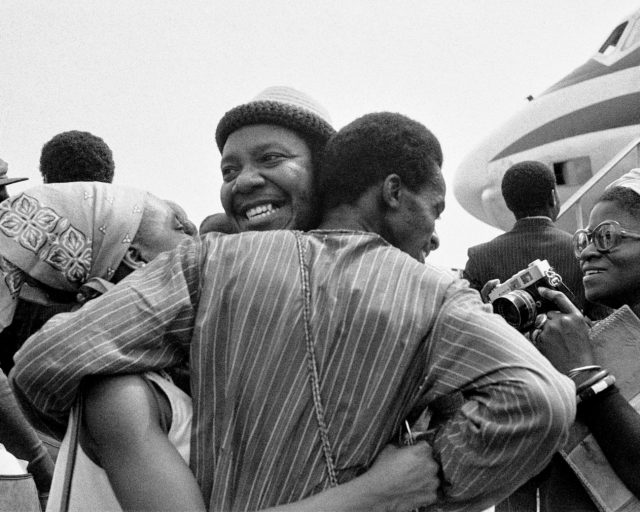

Ayana V. Jackson’s exhibition of radically speculative character portraits inaugurates the midwest home of a leading American gallery.

Ayana V. Jackson: Take Me to the Water, 2019. Installation view

Courtesy Mariane Ibrahim Gallery, Chicago

For more than seven years, the gallerist Mariane Ibrahim has provided a vital platform for African diaspora artists, bolstering the careers of, among others, conceptual British Liberian artist Lina Iris Viktor, German Ghanaian photographer and textile artist Zohra Opoku, and Nigerian British mixed-media artist Ruby Onyinyechi Amanze. Ibrahim recently decided to relocate her namesake gallery from Seattle to Chicago. The new space opened its doors on September 20, with an inaugural exhibition by photographer Ayana V. Jackson.

While Jackson’s previous work has examined archetypes of nineteenth- and twentieth-century photographic portraiture, her new series Take Me to the Water marks a shift in focus from historical references to speculative fiction. In both still portraits and fluid movement studies, Jackson explores an underwater world, an aquatopia, crafted from West African spiritual legacies and proto-Afrofuturist imaginings. This is Jackson’s third solo exhibition with the gallery. I recently spoke with Ibrahim and Jackson about their longstanding working relationship, the import of Take Me to the Water, and the gallery’s place in Chicago’s flourishing art community.

Ayana V. Jackson, Sea Lion, 2019

Courtesy Mariane Ibrahim Gallery, Chicago

Emma Kennedy: Mariane, can you talk about the decision to move the gallery from Seattle. What drew you to Chicago?

Mariane Ibrahim: One disadvantage, that started to become an advantage, is that in Seattle, we were actually isolated from the art market—so removed that you have a different paradigm, where you are developing your business away from all of these centers, away from all of these noises. But you still have the necessity of reaching out to those art markets and being present in those spaces. I had to get closer. We decided on Chicago because it’s central, it has a history, it has diversity. We have to be in Chicago, because Chicago is sophisticated enough to really embrace our program and artists.

I’ve always known that if I was going to open in Chicago, it was going to be with Ayana. Without knowing what work she was going to come up with—but the idea of opening and inaugurating the space with a black American woman was a statement of the direction we’re going in and a way of honoring the contribution of the black American woman in America, and also the history that Ayana is bringing to light.

Kennedy: I’m wondering, Ayana, if you could talk a bit about the work. My understanding is that it’s new work of yours, correct?

Ayana V. Jackson: Yes, it’s definitely new work. Take Me to the Water is marking a pretty significant shift in my practice. I’m dealing with kind of a speculative fiction arena. In previous bodies of work, I was looking at the history of photography or the history of portraiture or the history of fine art and the black body, and therefore referencing materials of existing artworks and/or photographs. This is the first time I’m inventing my characters from scratch. I’m still dealing with the archetype, but in this case, I’m thinking through new archetypes, or archetypes related to older mythologies.

It’s also a shift in that for the first time, I am creating the costumes. With the previous bodies of work, I was using costumes that came from opera houses, that came from costumiers in Paris. This time, I decided to collaborate with two fashion designers to create the costumes. I’m still working with my own body, as usual, I’m still working with black female identities, with the black woman’s body, but in a different, more speculative space. That would be the biggest shift in the work.

Ayana V. Jackson, Serene II, 2019

Courtesy Mariane Ibrahim Gallery, Chicago

Kennedy: How are you thinking about your body and performance in this new fictional world? Do you approach it differently than the archival work?

Jackson: Probably in the first couple bodies of work, I was dealing more with the static pose, like the portrait, the still body. The work has always been performative; I’ve never considered it self-portraiture, because I’m always performing a character. But there’s a lot more movement now. Each of my characters does have a static portrait, and you’ll see some of those in Take Me to the Water, but you’ll also see some movement studies. So, each character has multiple manifestations. Because this series is dealing with an undersea colony, this idea of an aquatopia; my characters are existing as much on land as they are existing in the deep, so every one of my characters has a form in movement, whereas that wouldn’t have been the case with previous bodies of work.

Kennedy: I was very intrigued when I was reading about the aquatopia, and the aqua-humanoid characters you’ve mentioned. Can you expand upon that world for us?

Jackson: Are you familiar with the myth of Drexciya? (It’s not common knowledge, though I’m by no means the first artist to deal with the subject matter.) Drexciya was a techno duo from Detroit that was functioning at the end of the eighties and early nineties. They originated before Afrofuturism was a topic, was even given its name. When you think about the forebears of Afrofuturism, you have a black cultural movement that was abstracting from the harsh realities of a place like Detroit or Chicago or the crack epidemic of the eighties and deciding to embrace a new foundation narrative. Drexciya was a band by two guys, and they basically said that they were the children of pregnant women who had been thrown overboard the slave ships, and that because the babies were able to breathe embryonic fluid, they could also breathe the seawater and therefore survive. It’s the idea that there are survivors of the Middle Passage who are living at the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean between the triangular slave trade. A friend of mine introduced me to the band. Techno has its roots in Detroit, and Drexciya was among those first DJs, those first founders of techno.

The project considers that aquatopia and other aquatopias that are related to traditional African spirit mythologies. The Yoruba, they have Yemaya, who’s the queen of the saltwater, the photosynthetic layer of the water; then you have Olokun, who’s at the bottom; and then you have Oshun. But then in places like Angola, you have Kianda; in places like Senegal and Benin, you have Mami Wata. I was offered a Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship (SARF), and I decided that I wanted to consider Drexciya and water-spirit iconography from countries impacted by the slave trade as one aquatopia. Then, I began to imagine a world where you have these ancient water spirits from the continent midwifing these pregnant women and birthing Drexciya. Take Me to the Water is my imagination of these precolonial African water-spirit mythologies intersecting with a twentieth-century black American Detroit imaginary of another aquatopia.

Kennedy: How do you anticipate viewers engaging with the work and this fascinating history?

Jackson: Some people will be familiar with my references, and some people won’t. I think that what I like about the work is that you can interact with my reference materials, or you can embrace it just as portraiture and performance and character-building. I like it when you can enter the work wherever you want.

Ayana V. Jackson, Cascading Celestial Giant I, 2019

Courtesy Mariane Ibrahim Gallery, Chicago

Kennedy: I love that. Mariane, I know the gallery started out with a focus on African and African diaspora art and photography, and it’s become more global over the years. What was the impetus for that mission?

Ibrahim: It’s true, my focus was really on African-descent artists and photographers. I think what was really missing [at that time] was the infrastructure for presenting African-descent artists and black artists in commercial spaces, so that they could be visible to the public, written about by the press, eventually picked by museums and institutions, and then finally come to the attention of the mass.

The artists have always been there; there’s no novelty in that. African artists and African American artists have always been there. But at the time, they didn’t have the commercial galleries to invest in them and push them forward. My gallery wanted to shape and change the market for emerging artists and artists from a certain geographic space.

Kennedy: Chicago is very happy to have you here.

Ibrahim: I think the gallery’s pursuit is to bring something different, relevant to the art community that is already so rich in Chicago. You can’t get more diverse than Chicago! I’m literally walking through Chicago with a big smile, because I’m amazed at how much diversity I see every day. And that’s very comforting. Puts us in a really good mind-set, a good setting to be able to develop our business.

Kennedy: Absolutely. The richness of Chicago’s history, specifically its black history, is endless.

Ibrahim: We are beyond excited to have Ayana and her new body of work. They are of a much larger scale. We also are partnering with Expo Chicago, and one of her photographs is going to be part of Override, [taking over a large billboard in the city]. Last year, Override featured Glenn Ligon and Judy Chicago. Ayana will also be part of that landscape, the urban landscape of the city of Chicago. I know she’s too shy to talk about these kinds of things, but it’s really an Ayana Jackson takeover of Chicago [laughs].

Jackson: If she’s going to put me under the bus for being too modest, I’m going to put Mariane under the bus for being too modest. This can be a very cutthroat market, and it’s refreshing and comforting to have someone like Mariane, who takes our careers personally. She takes our success personally; our success is her success and vice versa. I’m super humbled to have the chance to carry her banner as she steps into Chicago for the first time.

Ibrahim: I’m really touched. The last thing that I will say about Ayana, which will summarize everything: she’s the only artist—not that I work with, but the only artist—who can literally, like a compass, put her fist in the center, and reach to Europe, Africa, and America, in terms of the history, like no one else. She has that flexibility to move constantly and go backwards in time, and make a perfect circle on the different narratives that have been told, written, and also untold. That’s also why I think her work is really touching many fields: photography, anthropology, art history, everything. I think she is a great ambassador to our program.

Ayana V. Jackson: Take Me to the Water is on view at Mariane Ibrahim Gallery, Chicago, through October 26, 2019.