Barbara Probst’s Points of View

By photographing one scene from different perspectives simultaneously, Probst has devised a singular practice that pushes against the medium’s myths.

Barbara Probst, Exposure #120: Brooklyn, 1177 Flushing Avenue, 11.15.16, 5:06 p.m., 2016

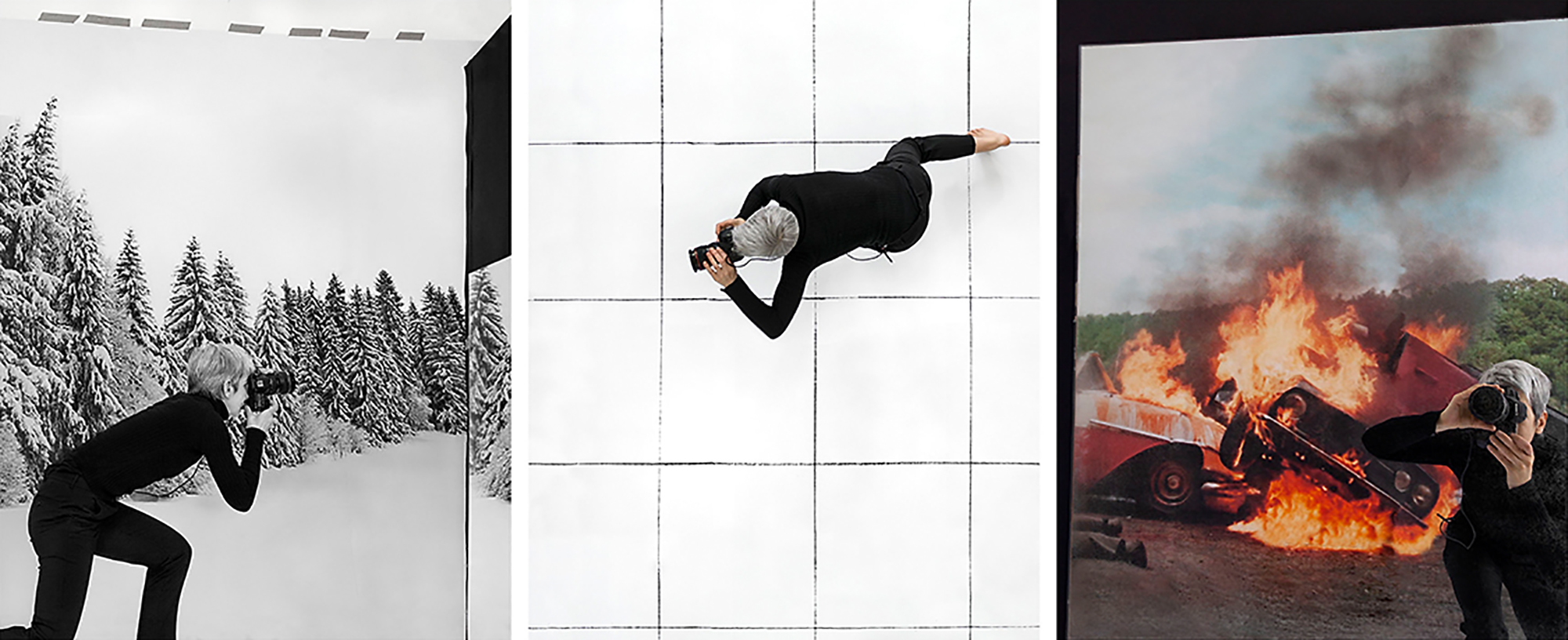

Twenty-five years ago, the German-born photographer Barbara Probst ascended a Midtown Manhattan high-rise, arranged a dozen cameras on tripods, and, at 10:47 p.m., leaped across the rooftop as an assistant triggered the shutters via a radio-controlled release system. The resulting grid of black-and-white and color images, a cross between Henri Cartier-Bresson and Michelangelo Antonioni, inaugurated the artist’s Exposures series (2000–ongoing), whose entries each consist of two or more photographs of the same scene, captured simultaneously at different perspectives and time-stamped with Teutonic precision, so that a single second shatters into a puzzle impossible to solve. The Exposures—which span landscapes, still lifes, fashion shoots, portraits, and street photography—may be read as philosophical treatises, each one coolly oppugning their medium’s purchase on the Truth. But they’re also beautiful, suffused with a surprising spontaneity and forensic mystery.

Below, the photographer discusses her work in the context of Barbara Probst: Subjective Evidence, a survey exhibition on view through February 9 at Cincinnati’s Contemporary Arts Center, which opened last November as part of the city’s seventh FotoFocus Biennial, Backstories.

Photograph by Jacob Drabik

Zack Hatfield: Zaha Hadid’s Contemporary Arts Center is so perfect for your photographs. The building has a kind of baroque interplay of spatial compression and expansion that we find in your work too. What was it like making the exhibition here?

Barbara Probst: I came here a year ago with Kevin Moore, the curator of the exhibition, to look at the space. I immediately liked the architecture, because of all these different vantage points and the possibilities of creating relationships between the works in it. My assistant made a model of the space to see how the works can be placed in relation to each other. And it was a very difficult model to build. Hardly any ninety-degree angles.

Hatfield: You also make models for your actual photoshoots as well, right?

Probst: Yeah, or drawings. Sometimes I make clay figures of the people I’m photographing to better imagine how they relate to each other in the shoot and to figure out the angles and viewpoints of the cameras. Shooting with several cameras simultaneously is a complex procedure and needs to be prepared very well.

Hatfield: People associate your exposures with meticulous orchestration and preparation, but there’s also a lot of improvisation that goes into it.

Probst: Sometimes I feel like a film director with all the details of a scene and all the viewpoints of the cameras in my mind before the shoot. Only when a shoot is planned and set up very accurately can I allow chance and improvisation. And often these unforeseeable changes add something really interesting to the pictures that I couldn’t have envisioned beforehand.

Hatfield: Is there an example of a work in this show that turned out differently than you originally envisioned it?

Probst: Most of them are close to my conception. You need to realize that I hardly ever look through one of the viewfinders during a shoot. Usually, I find a position hidden from the cameras, and from there I release the shutters simultaneously. That’s why my control is limited. Envisioning a shoot and the outcome of the images is one thing—the realities during a shoot, another. For example, Exposure #106 was a shoot on the street with several models inside a building linked to an unstaged scene with a yellow cab on the street downstairs. The shoot was made with twelve cameras. I conceived the twelve images very precisely beforehand, but there was much going on in the shoot that was beyond my control. But even in a shoot like this, I came very close to the images I had in my mind. The works made in the studio, like the close-ups and still lifes, are much more controllable and calculable. It’s a very different way of working for me.

Hatfield: How do you see your work’s relationship to narrative?

Probst: To look simultaneously from different perspectives means to give up the single point of view to which we’re accustomed. It also means no longer believing that the narrative emanating from that single viewpoint is reliable or truthful. I feel that my work actually has a lot to do with life. We all are here on this planet at the same time, and we all look at this world in very different ways. What I have learned from my work is that instead of choosing one way of seeing or another, it’s much more realistic to acknowledge many. In today’s world, this might sound disconcerting, but it can also be a relief to recognize that we don’t really know.

Hatfield: There’s a fascinating relationality that emerges through this distinct triangulation of photographer, model, and viewer. Your pictures ask a lot of the viewers’ imagination.

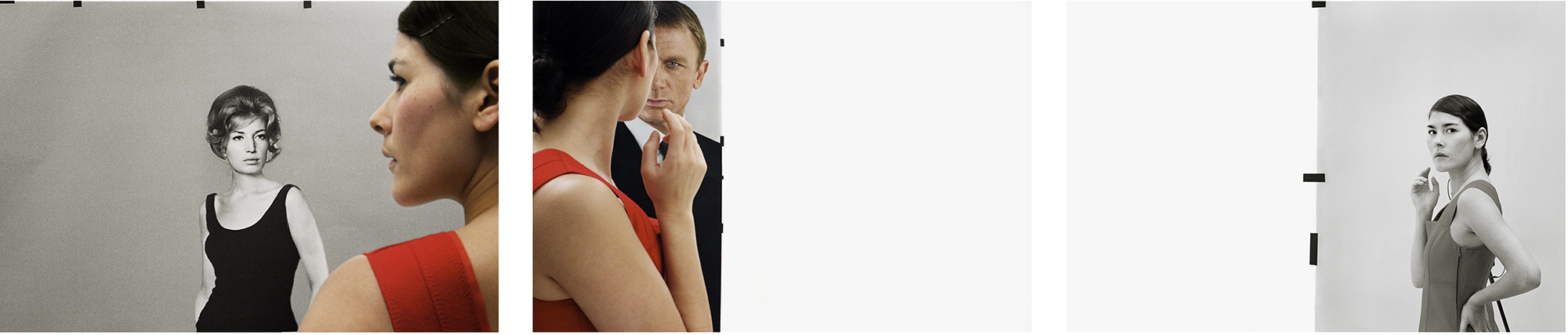

Probst: Yes, in some works, I try to draw the viewer into the images by creating this kind of triangulation. For example, in Exposure #87, there’s the space in which the model is located; there’s the space of the photographer in the backdrop on the wall of the studio, and there’s the “real” space of the viewer, all of which overlap and interact. The viewer is an essential part of the work.

Hatfield: I’m interested in your beginnings as a sculptor. I know you were inspired early on by Rodin’s public statue The Burghers of Calais (1884–95), specifically how the figures are arranged nonhierarchically.

Probst: I chose a very classical training as a sculptor, which included daily nude modeling and drawing in the first year. Then I made abstract sculptures and later sculptures that included photography and finally installations containing sculptures and photographs before I dived deeply and exclusively into the medium of photography by starting the Exposure series in January 2000. I still feel that my work is very sculptural. Looking at something from different viewpoints is a sculptural interest. The Exposures can create a spatial impression in the mind of the viewer. The nudes, for example, are the works coming closest to this impression. I look at a nude from different angles, just like a sculptor while modeling one. These nude exposures are a nod to the classical genre of nudes, but they also break with it at the same time by reflecting the making of the pictures by showing all the cameras shooting the nude.

Hatfield: The museum’s wall text draws a connection between the multiple perspectives at play in your work and this idea of empathy—of trying to share the experiences of other people. Yet I feel as though your work dramatizes the limitations of knowing other people. Is your work about trying to experience the world from other peoples’ viewpoints?

Probst: You said it beautifully: It dramatizes the limitation of knowing other people. The limitation of knowing how they see the world. With our pair of eyes, we are somehow lonely. Nobody other than us can see from that point of view. This realization certainly comes through again and again in my work. Having said that, I’m also interested in empathy, which enables us to inhabit other points of view. To experience empathy, imagination is required.

Hatfield: You don’t call your photographs portraits, but close-ups.

Probst: There are works of mine that refer to the genre of portraiture, but they aren’t portraits, because my work is never about the people, their character, or their personality. It’s the relationship between them and the viewer I am interested in, the back and forth of gazes—the gaze of the protagonists at the viewer and vice versa. For example, in Exposure #124, two women look at two different cameras. When you stand in front of the images, the two viewpoints of the cameras merge into one in your eyes. The viewer’s otherwise all-so-certain point of view is in question here.

Hatfield: Throughout the show, it’s remarkable how the subtlest change to an angle can completely transform a composition and its emotional content.

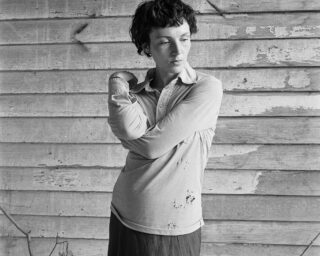

Probst: Often a slight difference in viewpoint can make you see a completely different image, a completely different narrative. Like Exposure #48, the cameras weren’t far apart. But in one image, she seems to be very present and aware of being photographed, and in the other image, the mood is completely different. She looks dreamy and deep in thought.

Photograph by Jacob Drabik

All photographs courtesy the artist

Hatfield: Has your understanding of your own work changed in the almost twenty-five years since you did the first Exposure? Social media has enabled this sort of global simultaneity to accelerate at an unprecedented scale, and the idea of photographic truth has been pretty thoroughly vitiated.

Probst: It certainly has changed over the years. I started out being very conceptual. My interest in the relationship between photography and reality compelled me to conceive Exposure #1 and many other series afterward. Twenty-five years ago, this was a subject less questioned. Today, photography still has a tremendous influence on our subconscious as well as our conscious mind. This issue is inherent to my work, but it moved into the background over the years. Other aspects within the principle of simultaneity emerged, and I immersed myself in different photographic genres. And in more recent years, there’s more playfulness, and often there are references to painting. The still lifes, for example.

Hatfield: You’ve mined this concept for so long without exhausting its potential. You’ve been able to breathe new life into it through what you describe as tropes or clichés.

Probst: Thankfully yes. Exposure #1 is the base of all these works. After I finished it, I knew that there was much more to explore. I do have challenging phases of reflection and research, but usually I emerge refreshed, with new ideas. I’m currently occupied with new work that explores a field I haven’t entered before. But since I’m still in the middle of making it, I don’t want to say too much.

Barbara Probst: Subjective Evidence is on view through February 9 at the Cincinnati Center for Contemporary Art.