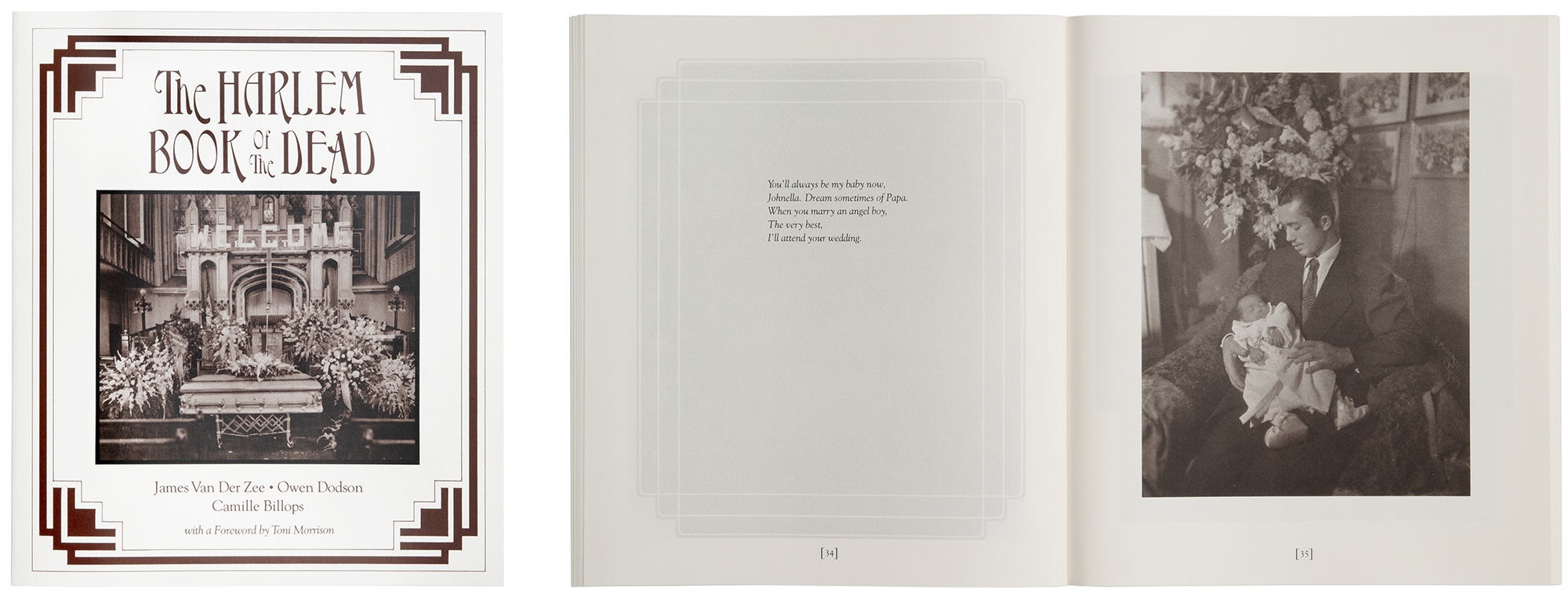

James Van Der Zee, from The Harlem Book of the Dead (Primary Information, 1978/2025)

James Van Der Zee and Garrett Bradley were born nearly one hundred years apart. What unites them across the snap of a century is a deft capacity to make visual hymns of Black life with their cameras, without overdetermining the lyric of that living. It’s fitting, then, that Van Der Zee’s The Harlem Book of the Dead—first published in 1978 and out of print for nearly fifty years—sees a second coming at the behest of Bradley, the artist and director celebrated for her Oscar-nominated 2020 film Time, in the form of a facsimile edition.

A dwelling place for Van Der Zee’s funerary portraits, The Harlem Book of the Dead encircles the deceased with a chorus of voices: an interview between Van Der Zee and Camille Billops, who conceived the original text; poetry by Owen Dodson; and a foreword by Toni Morrison. As managing editor of the reissued edition, Bradley retained the original contributions as well as Billops’s approach to polyvocal book-making, commissioning a new afterword by Dr. Karla Holloway, who writes: “Van Der Zee is speaker for the dead. . . . These images secured the souls of Harlem’s Black folk.” As speaker and “securer,” Van Der Zee and his images attend to the belief that death is not an end, nor a terminal point, but rather a threshold, a passageway interminably open on both ends. By exhuming his elegiac photographs alongside the liturgy that cradles them, Bradley carries forward a longstanding Black tradition in which the living are called to caretake the desires of the dead.

Camille Bacon: What was your first encounter with The Harlem Book of the Dead and Dr. Karla Holloway, who authored the facsimile edition’s afterword?

Garrett Bradley: I was taking Professor Kevin Quashie’s class Death and Dying at Smith College, which introduced me to Karla Holloway’s book Passed On: African American Mourning Stories (2002), which begins with her own personal experiences with grief. From there, it builds into a set of queries that brings readers into the history of Black death and dying in America over the course of a century.

Holloway contextualizes Van Der Zee’s work in particular within the early 1900s and mid 1920s as running parallel to the Red Summer of 1919, the high child-mortality rates in New York City because of the rise in tuberculosis and pneumonia, and eventually both world wars. In the same way that Van Der Zee took a radical approach to his subject matter, mourning and death, Holloway was also introducing us to a new way of understanding the personal alongside the historical. Both bodies of work—The Harlem Book of the Dead and Passed On—propose the impossibility of separating personal grief from the collective experience of grief. Our proximity to it may begin intimately, but what happens next, our journey through it, our attempts to do something with it, are a universal pursuit. I owe a great deal to Quashie for opening that door for me as a student and then introducing Karla and I years later. Karla and I have since become good friends and are in the process of adapting Passed On into a new body of work.

The process of conducting research for the adaptation of Passed On is also what brought me to The Harlem Book of the Dead. It was originally published in 1978 by Morgan & Morgan. When they closed their doors shortly after the book’s release, it quietly slipped out of circulation. That initiated a second and separate endeavor, which was to bring The Harlem Book of the Dead back and to do so in a way that retained the original approach conceived by Camille Billops. She was the glue that brought Van Der Zee, Dodson, and Morrison together. James Hoff, the executive editor at Primary Information, was immediately supportive in helping to bring the book back to life. The only modification to the facsimile edition is the addition of Holloway’s afterword. I think her perspective offers something unique and valuable for those encountering it for the first time.

Bacon: One thing that struck me about Billops’s original impulse to compile these images in a book, which is a form that can be shared widely, is it also means these images are pulled beyond their original context. From my understanding, loved ones of the deceased would commission Van Der Zee to make the photographs included in the book and thus I imagine they were originally placed on a mantelpiece in a family home, or maybe in a scrapbook or photo album. When they’re gathered in a text, they circulate in the public arena. What does that kind of contextual shift mean?

Bradley: I’m thinking about [the Studio Museum in Harlem director] Thelma Golden’s framing of Van Der Zee’s body of work as one that operates as documentation of the Harlem Renaissance but also a “family album” of Harlem as a whole. Van Der Zee talked about his hope for the images in The Harlem Book of The Dead to operate on a formal level that is well beyond documentation and exemplifies his interest and pursuit in having the images go beyond a direct read. The book itself is its own kind of universe and context.

Van der Zee was born in Massachusetts about twenty years after the Civil War. He moved to New York briefly with his father and did odd jobs. He then started a family and left New York briefly, then moved back to Newark and developed his photographic practice, where a good portion of his work was commissioned by a local church. From there, he opened his own place on 272 Lennox Avenue. His arrival in Harlem was really the beginning of the career that defines him. Owen Dodson was thirty years younger than Van Der Zee and grew up in Brooklyn. He was a playwright, a novelist, a poet, and a scholar. Camille Billops was the youngest of them all. She was around fifty years younger than both Dodson and Van Der Zee and was a sculptor, a filmmaker, an archivist, an educator, and an organizer. Billops’s works came so much from bringing people together, and she had a natural instinct that makes the collaboration in this book feel somehow inevitable. And Morrison, who wrote the foreword for the book, was actively shifting the entire literary landscape as a writer. Each of them gave themselves, and their work, permission to be articulated in as many different forms and shapes and styles as necessary.

Bacon: What you’re saying reminds me of this quotation from Toni Morrison’s foreword where she describes Van Der Zee’s photography as “truly rare—sui generis.” What is so clear in his pictures and so marked in his words is the passion and the vision, not of the camera but of the photographer.” A central facet of Van Der Zee’s approach was his editing practice, which feels singular and not only “sui generis,” one of a kind, but also ahead of its time. In the book, he talks about smoothing someone’s wrinkles or adding inserts of angels into the frame so the subject has a companion in the afterlife.

I know you’re deeply involved with the editing of your own films and have spoken about how the editing process is where you get “closest to actually touching your own work” and how physical it can be. I’m curious to hear you speak further about how we might interpret Van Der Zee’s modification of his own images.

Bradley: We live in an elusive time. It’s very hard to touch anything in a digital era—or to be touched. But Van Der Zee was living in an analog world, and when we’re talking about “editing,” there are many ways of looking at it. There are the embellishments that come in the form of painting, collage—a layering of imagery and the photographic negative that operates as storytelling, historical clarification, or correction. [Van Der Zee’s modification of the images] also operates as transcendence and empathy visualized. It connects the personal and the collective. This is where the images exist beyond the subject matter.

There is also a strong element of glamor and of editing for “perfection.” Softening the face, removing the wrinkles, adding a twinkle to the eye. I would say a major difference that shifts the way those changes operate in, for example, a magazine, then and now, is that these images are solely for the people receiving them. The edits become an act of generosity as opposed to a rejection of the viewer or narrowing of what’s accessible.

Bacon: Absolutely. It’s almost like his edits, especially the insertion of angels or scripture into the images, become additional speculatory material that’s particularly tailored to how Van Der Zee imagined the idiosyncrasies of the subject in the frame, not just what’s “really” there.

I was also so taken by the rhythm of the book’s organizational structure. We meet James Van Der Zee by way of his language, before we meet his images. After Morrison’s foreword and Billops’s introduction, we are carried directly into Van Der Zee and Billops’s interview, then you get the lyricism of Dodson’s poetry, and then we submerge into the totality of all of those elements as Dodson’s verses are punctuated by the images. What do you make of the book’s rhythm and how the multitude of voices in this chorus—Morrison, Billops, Van Der Zee, Dodson, the images themselves, and now Holloway—are introduced to us?

Bradley: The book’s spine, so to speak—what really holds the book together—is the dialogue between Billops and Van Der Zee, which encompasses his life story and creative practice. Their discussion unfolds alongside the work, and to the left is Dodson’s writing, which I think acts kind of as an open-ended verse that is not necessarily narration or captioning but parable—something between scripture and query. They can operate as a guide, or even as something that’s contradictory to the image. There’s a lot of openness that exists there, and I think that that’s how the interview between Van Der Zee and Billops also operates in this. Going back to these questions of, What is photography? How does photography operate?, we understand it’s not just documentation because we’re not just getting descriptions of what we’re seeing. We’re in a much different place that is deeply emotional. I think even with all these elements, the book is beautifully unified while also being spacious or timeless, really.

Bacon: I’m interested in how this book resolutely differs from the stream of images of Black death that we’ve been encountering en masse for some time, especially through our phones. The work in The Harlem Book of the Dead feels contrapuntal, like a countermelody to the conditions that create those images and the velocity at which they circulate. There’s a slowness and a stilled-ness—to riff on Holloway’s afterword—to them that injects something devotional that is absent from images of Black death that are captured against our will.

Bradley: What makes this body of work really stand apart from something that we might be seeing on a regular basis or being inundated with today is that the images that are proliferating throughout the internet and that have historically existed around Black death have never been for us. These were portraits that were given to family members as mementos. They weren’t just taken and then put into a news outlet. There was a lot of care and a lot of love. It’s almost like a eulogy that has been visualized and placed into the photograph. I think that that’s where they really stand apart, and that’s a key point.

Bacon: The Harlem Book of the Dead inhabits the emotional environment of life’s limit in such a profound way. I appreciated the way that the writing and images in the book create a scaffold for others to write about bereavement, make images of mourning, and also create language and images that themselves grieve.

Bradley: I think Karla Holloway articulated it best in asking, “Where does one find grief’s conclusion?” She found a compromise with it in the process of writing and in art and in the process of making. The Harlem Book of the Dead is an apt example of that same question. To quote Marcel Proust, ideas are successors of grief, which says to me that America’s culture, aesthetic, and every innovation it has produced has come from grief, and I think this book is also a remarkable example of that.

Bacon: Each of the original collaborators dedicated the book to someone or a group of “someones.” Who or what might you dedicate this facsimile edition to?

Bradley: I think everybody in the world right now is living with grief and trying to navigate its presence. We create things out of it, and that is essentially its purpose: to build something from it, to move through it, and to continue to contribute to the world in a way that helps us continue to understand and process one of the most human and unavoidable emotions that there is. Grief will never go away. It’s a part of our experience here.

It’s also not something we always have a clear understanding of how to move through, particularly as modern people who have been predominantly separated from any original tradition or have replaced it with the idea of being an individual. I might dedicate it to this moment, an era of great global grief as a reminder of the potent and loving power that can be born from it.

© James Van Der Zee Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and courtesy Primary Information

Bacon: Your response, namely when you said it “will never go away,” makes me think about something specific [Smith] Professor Samuel Ng, who teaches a course called the Politics of Grief, has said about grief: Black grief is pathologized for a multitude of reasons, but especially because of the way it endures, how because a central cause of our mourning, the conditions that beget and necessitate Black death, have not ceased; our grief keeps coming back. It’s cyclical, and it refuses to end within an amount of time deemed “appropriate.” It’s those “circles and circles of sorrow” Toni Morrison describes at the end of her novel Sula. Throughout The Harlem Book of the Dead, grief and its duration are characterized not as some kind of malady but as symptomatic of a life lived on the ledge of recurring disaster—and a life that is still verdant and vibrant amidst it all.

In our last couple of minutes, I would love to linger with one of the images together.

Bradley: Let’s turn to page fifty-three. A young woman lays in an open casket, adorned with lace and white flowers. Jesus holds a baby lamb and looks down at her on the upper right-hand corner of the frame.

It was Holloway’s work that connected the dots between Van Der Zee and Morrison. Toni Morrison’s character Dorcas in her 1992 novel Jazz was inspired by this image. In the novel, Dorcas is shot by her lover but lets him get away because she loves him. To the left of the image, Dodson’s verse further connects the four artists—Van Der Zee, Morrison, Billops, and Dodson himself—across time and story:

They lean over me and say:

“Who deathed you who,

who, who, who, who . . . .

I whisper: “Tell you presently . . .

Shortly . . . this evening . . . .

Tomorrow . . .”

Tomorrow is here

And you out there safe.

I’m safe in here, Tootsie.