Bruce Conner's Rebellion

In film and photography, the subversive artist confronted American life in the Atomic Age.

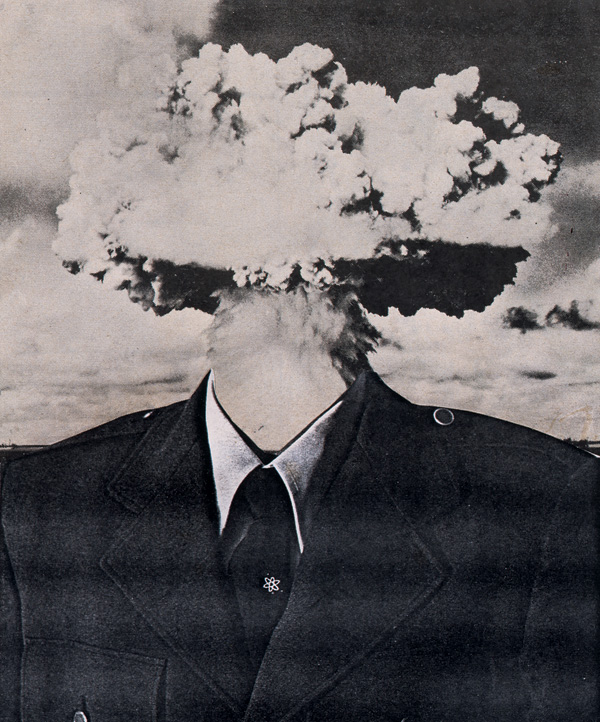

Bruce Conner, BOMBHEAD, 1989. Collage of found illustration and photocopy

© the artist and courtesy Conner Family Trust and Artists Rights Society, New York

Kansas-born counterculture hero Bruce Conner has been something of an enigmatic figure in New York, despite several recent monographic exhibitions at Paula Cooper Gallery. The Cooper shows tended to focus so closely on Conner’s projects or series—for example, with his Max Ernst-like collages of found illustrations from the 1960s—in a space so small that it was hard to step back and get a view of the breadth, ambition, and interconnectedness of Conner’s radical practice. By contrast, Bruce Conner: It’s All True, organized by Museum of Modern Art and SFMOMA curators Stuart Comer, Laura Hoptman, Rudolf Frieling, and Gary Garrels, is a wide-ranging examination of Conner’s films, photographs, works on paper, and sculptural assemblages that gives exactly the broad view that previous exhibitions lacked.

Bruce Conner, LOOKING FOR MUSHROOMS, 1959–67. 16mm film, 3 minutes, color, sound

© the artist and courtesy Conner Family Trust

In this exhibition, the artist’s prescient commitment to subverting image-culture emerges clearly. From the first work on view, A MOVIE (1958)—a twelve-minute genre-defying collage of appropriated footage rhythmically edited to pop music—Conner can be seen as a forefather of the Pictures Generation. His assemblages of the 1950s and early 1960s are mystical-looking, Merz-like compositions. Dolls’ heads and costume jewelry crop up from dusty-looking surfaces; these feature cut-out photographs from “girlie” magazine pages alongside the postage stamps, nylons, bobby pins, and metal foil. Pictures are brought together in omnivorous disregard for a distinction between “high” and “low” art and life, popular culture and museum culture, just as his great films collage go-go dancers and bra ads. Of course we know Rauschenberg was making “Combines” on the East coast, but Conner’s pieces—PORTRAIT OF JAY DEFEO (1958), PORTRAIT OF ALLEN GINSBERG (1960)—are the West coast contemporaries often obscured in art history.

Installation view of Bruce Conner: It’s All True at The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2016

Photograph by Martin Seck © The Museum of Modern Art

Among the crowd-pleasers are the life-sized “Angels” Conner made with photographer Edmund Shea. The angels are haunted photograms, full-scale traces of a fleeting presence—the artist himself posed against sheets of photosensitive paper. In SOUND OF ONE HAND ANGEL (1974), a palm pressed into the center of a grey torso creates an opaque white shape that looks like a clenched heart. Adding to the darkly romantic effect is the sound of live crickets, playing here as they did when the works were first exhibited in Berkeley, California in the mid-1970s. Conner also appropriated photographs of people bearing the same name as him: “Bruce Conner for Supervisor,” and “Bruce Conner’s Physical Services,” two such images read. Subverting mechanisms for self-promotion, these images are resonant with the practices of artists of our time, including works by Merlin Carpenter and Josh Smith.

Bruce Conner, BREAKAWAY, 1966. 16mm film, 5 minutes, black-and-white, sound

© the artist and courtesy Conner Family Trust

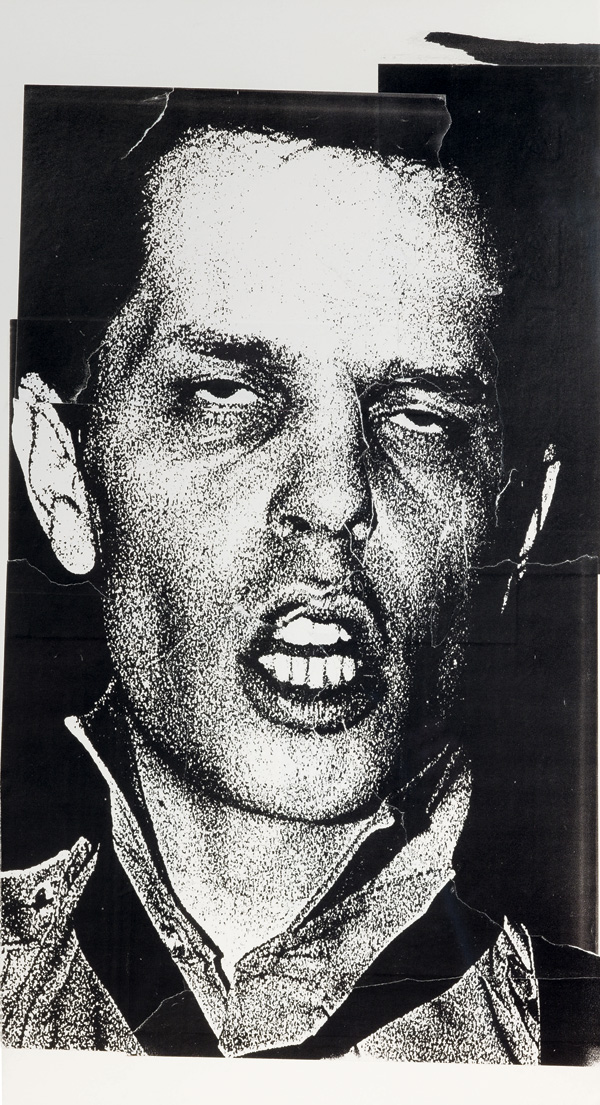

The most mysterious of Conner’s photographs were originally taken for the magazine Search and Destroy during the late 1970s at the San Francisco punk venue Mabuhay Gardens. These are not composed of pastiched elements, nor are they metaphysically leaning—instead, they are documentary snapshots of musicians and rapt punk audiences. Why would Conner make such “straight” pictures? Maybe the answer lies in style: the punks are themselves chaotic clashes of social signifiers, layering military uniforms, thrift store business suits, biker accessories, and schoolgirl skirts in a glorious collage. Conner’s interest in their style bridges Dada and punk—both favor DIY as ethos and je m’en foutisme for attitude. Later, Conner’s collages of the 1990s consist of pasted-in catheters, gauze, pills, and flyers surrounding the punk photographs. The ’90s work is not his best art or his best photography, but it’s smart and prescient; it reminded me of Seth Price’s tight, hyperlinked essays about culture in which images and object are shorthand for styles and their availability for pastiche.

Bruce Conner, FRANKIE FIX, 1977. Collage of photocopies on board

© the artist and courtesy Conner Family Trust and Artists Rights Society, New York

What was photography to Conner? A way to play with the simultaneous presence and absence of the artist in an artwork, a mechanism fix those ephemeral traces taking the pulse of throwaway culture and open them up to appropriation and collage. Conner’s acquisitive appetite for source material suggests that while photography has long generated new images, an equally important role has been to replicate and reuse extant ones. His images and films transform pop culture because of the availability of styles to get picked up and recycled, and propose that art is located in countercultural gestures of rebellion and resistance to the dominant image culture. Anticipating the East Coast appropriation of the late 1970s and giving some much-needed clues to the media-saturated DIS generation of today, Conner’s work, in this show, is more vital than ever.

Bruce Conner: It’s All True is on view through October 2, 2016 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The exhibition will travel to SFMOMA, October 29, 2016–January 22, 2017, and the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia in Madrid, February 21–May 22, 2017.