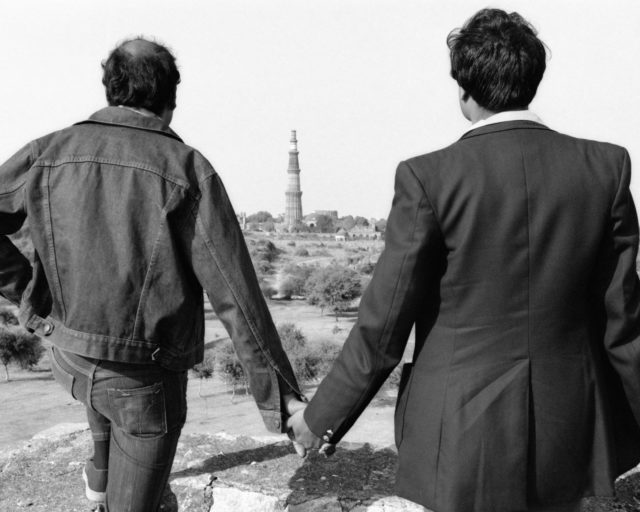

Bruce Weber, Keith, Pete’s Rock Campground, Adirondack Park, New York, 1990

Prague is a place shot through with satire. Kafka is considered a sort of mascot and the sculptures of David Černý—two men pissing onto a Czech Republic–shaped fountain’s basin, King Wenceslas riding his horse upside down, Sigmund Freud hanging from a flagpole—remain some of the city’s most visited attractions. Bruce Weber’s art, such as the pieces in his first retrospective My Education, which was on view last fall at Prague City Gallery (GHMP), is decidedly not satirical. A photograph titled The Duchess of Devonshire Feeding Her Chickens at Chatsworth (1995), for example, isn’t meant as social commentary, even if the duchess, Deborah Cavendish—whom Weber met through her granddaughter, the fashion model Stella Tennant—is feeding said chickens from a dented tin bucket while wearing diamonds and pearls. Taking in the 250-plus photographs and videos at GHMP’s Stone Bell House, I wondered: Why here? And, considering Weber currently occupies a gray area of that graying concept of “cancellation,” why now?

Born in 1946, Weber left a Pennsylvania farm town to study film at New York University, and with help from his sister Barbara (then head of publicity for United Artists Records), found himself snapping photos of famous musicians: David Bowie, Ike and Tina Turner, Frank Zappa, Iggy Pop, Patti Smith. Next, a move to Paris, then back to New York to study at the New School under Lisette Model, whom he’d met through Diane Arbus. On a go-see in 1973—he modeled, too—Weber met Francesco Scavullo’s studio manager, Nan Bush, who became his agent, getting him his first fashion photography jobs: Dillard’s, GQ, and Ralph Lauren, with whom he would work closely for forty years.

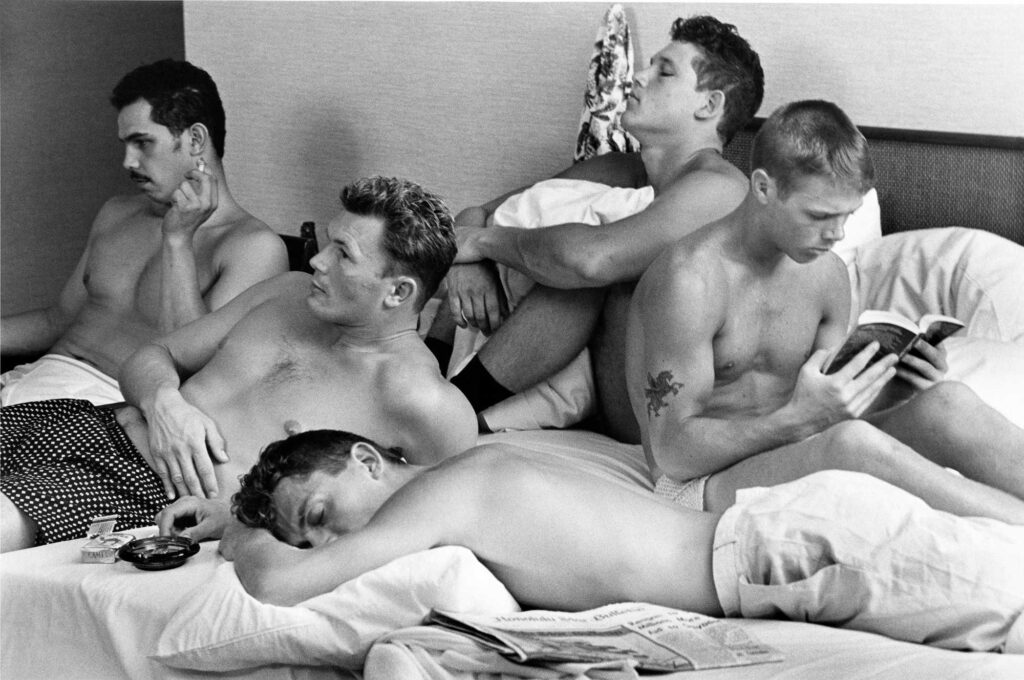

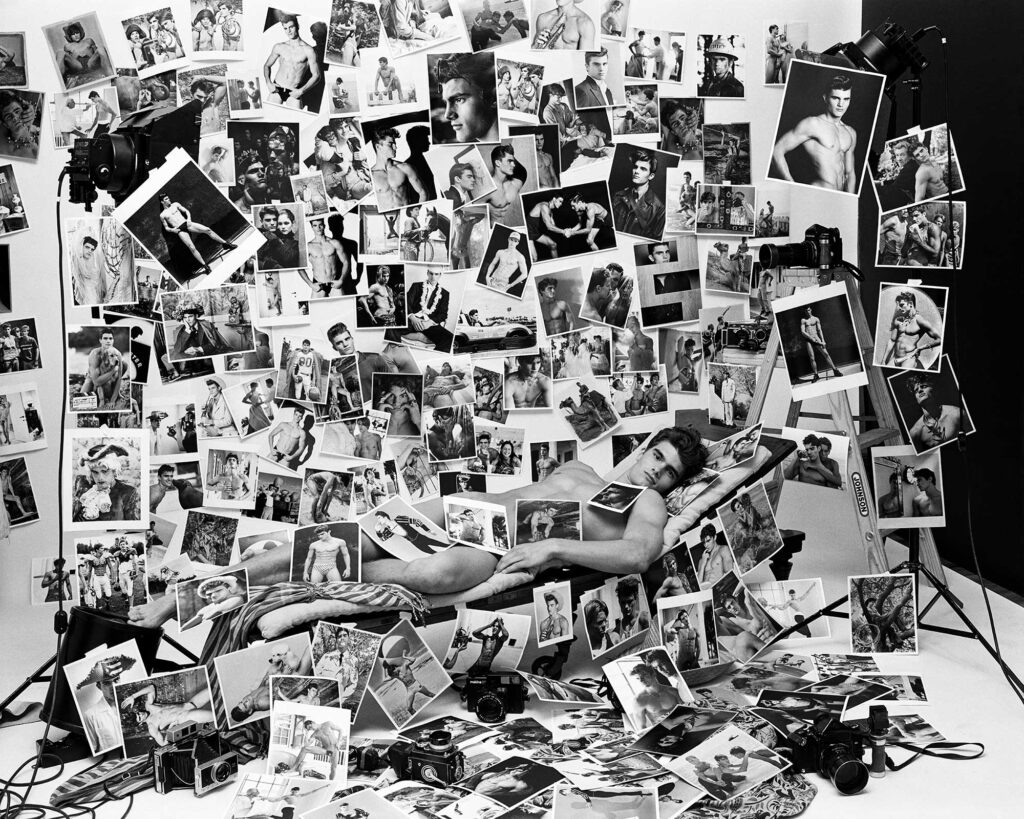

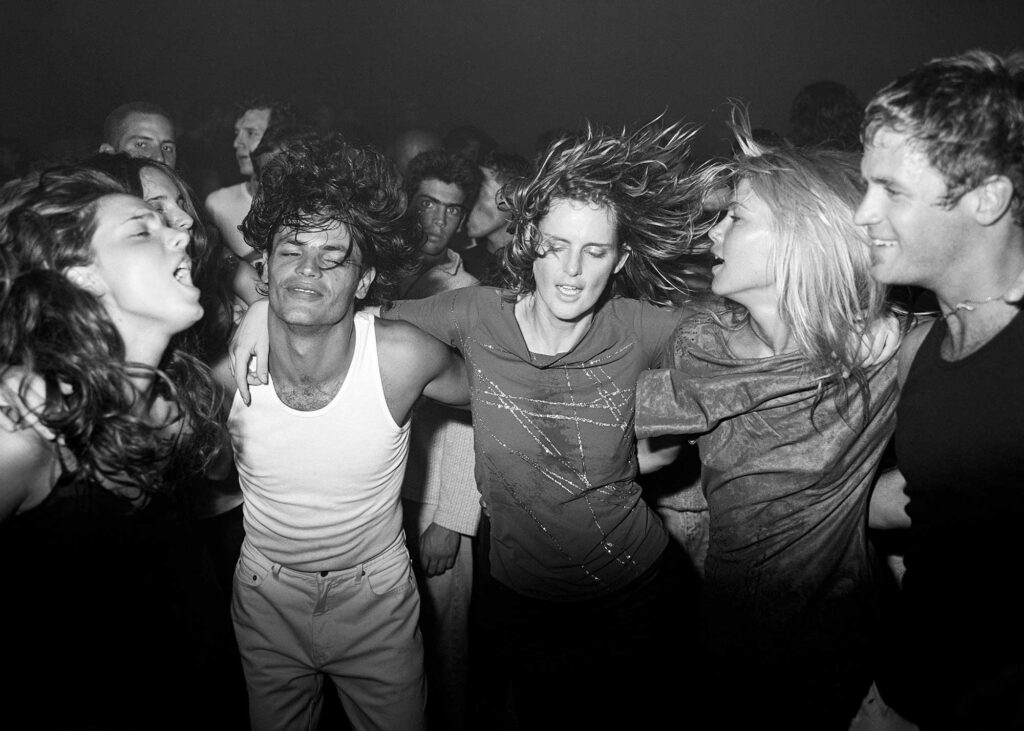

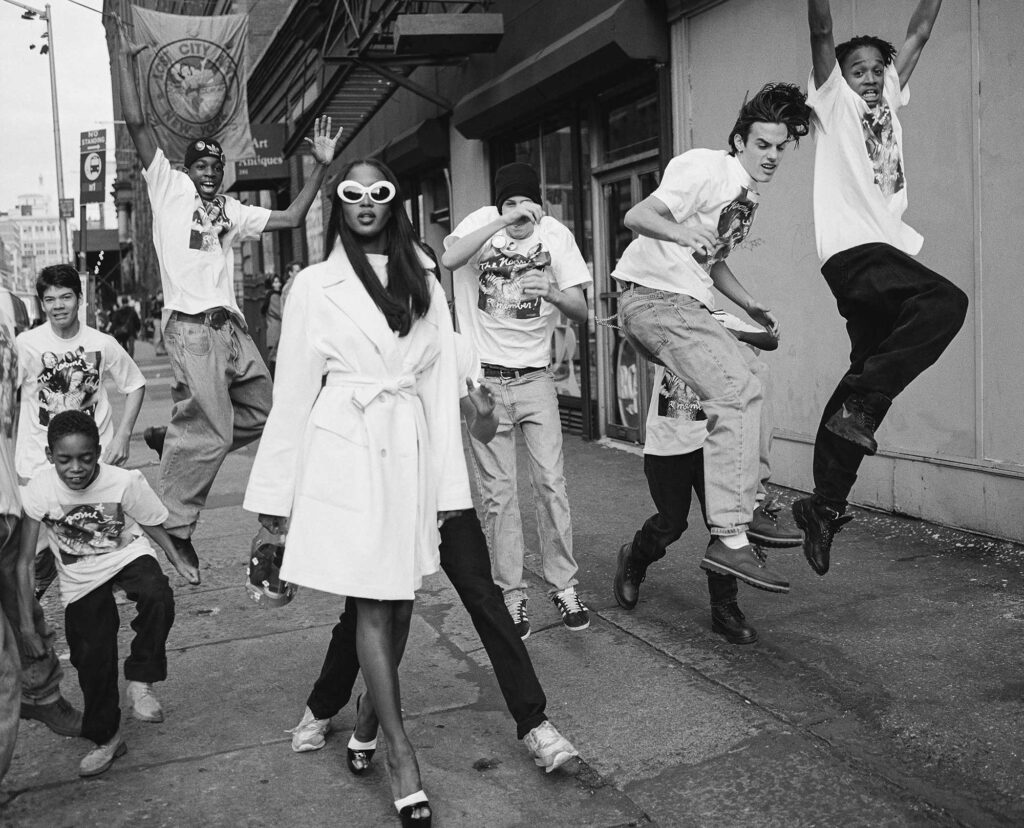

In 1978, Weber shot a Calvin Klein jeans campaign, and in 1982, the brand’s first underwear ads. Throughout the 1980s and ’90s, his billboards caused a sensation, putting Waspy Adonises in blatantly seductive poses at massive scale. He developed an eye for interpreting artifice through the hallmarks of authenticity—imagine Dust Bowl documentary as Italian Neorealism, behind-the-scenes of pageantry, serious jocks goofing off. His photographs made up, in large part, the infamous plastic-wrapped Abercrombie & Fitch Quarterly (1997–2007)—a commercial catalogue that people actually paid for, with a peak circulation of over a million—which, depending on the critic, was an ingenious marketing tool or camouflaged pornography.

For generations, magazine readers, mallgoers, and the habitues of galleries and museums encountered Weber’s singular but widely imitated style. Then, in 2017, he was accused by a male model of unwanted sexual advances. Others soon voiced similar sentiments, and most of his contracts promptly ended. Today, his vision remains ubiquitous, even as his name is decreasingly evoked in advertising and editorial meetings. Newer fashion brands are publishing campaigns that directly reference A&F’s homoerotic preppy handbook, perhaps most notably Raimundo Langlois, who has said of his own denim- and khaki-centric label, “It’s perversion of the familiar. It’s memory reconstruction.”

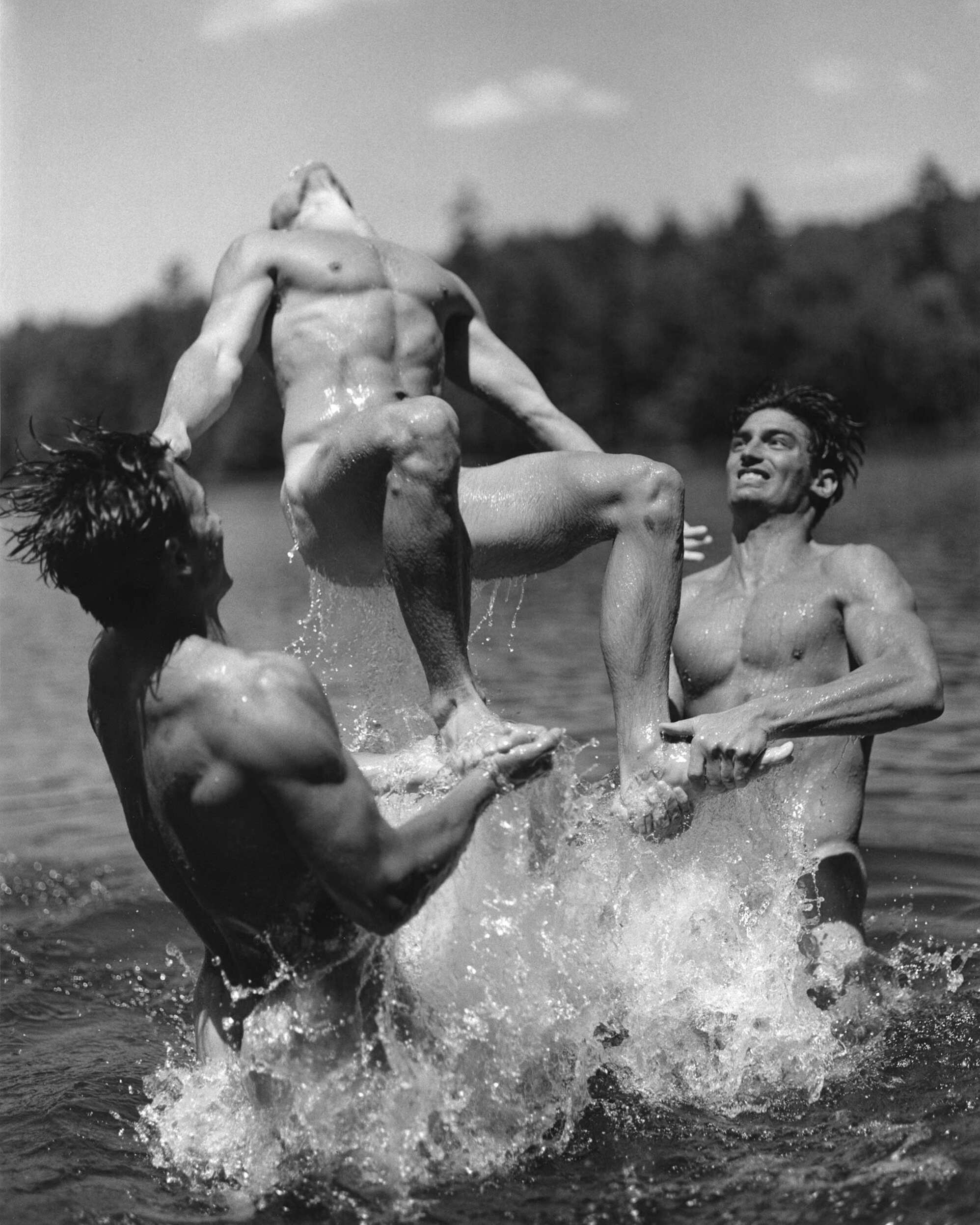

“What I love about Bruce Weber’s work is the possibility of being subversive within the most mainstream of channels,” said Matthew Leifheit, a visual artist who has appropriated A&F merchandising in his own photography. Leifheit discovered Weber’s work in the mall when he was growing up in Wisconsin. “I was seduced by the matter-of-factness of his photographs, thinking I wanted to be these guys, when truly I wanted to have them. Later, I recognized the pictures were transparently referencing a lineage of setups for ‘physique photography’ as well as the history of more formal gay erotica including George Platt Lynes and Wilhelm von Gloeden.”

Weber’s dozens of monographs may amount to hundreds if we are to include catalogues and a self-published semiannual, All-American, now on its twenty-first issue, but a forthcoming book from Taschen, Bruce Weber: My Education, will mark the seventy-eight-year-old’s first official career survey. The book’s title refers to Weber’s own creative maturation, but the work provides so many markers of a zeitgeist, it naturally reflects our education as well. Beyond fashion callbacks, all the super-staged spontaneity, smiling bodybuilders, and rural stars-in-waiting now found on our social media feeds feel at times derived from that same bizarro America that Weber started to dream up about four decades ago.

Weber is attributed as an originator of what we now call lifestyle branding, a way of generating desire through imagery that isn’t product-oriented yet results in product sales. The ads for which Weber became in demand sold people and places, not clothing. How could a catalogue of nearly or naked youths horseplaying in the woods translate to a successful sportswear company? Ask anyone who couldn’t stay away from A&F stores as a teen. How did Calvin Klein, with its decidedly plain underwear line, become the essential logo on an elastic waistband? That arguably had much to do with Weber’s photograph of an Olympic pole-vaulter, which froze traffic when it appeared on a billboard in Times Square in 1983.

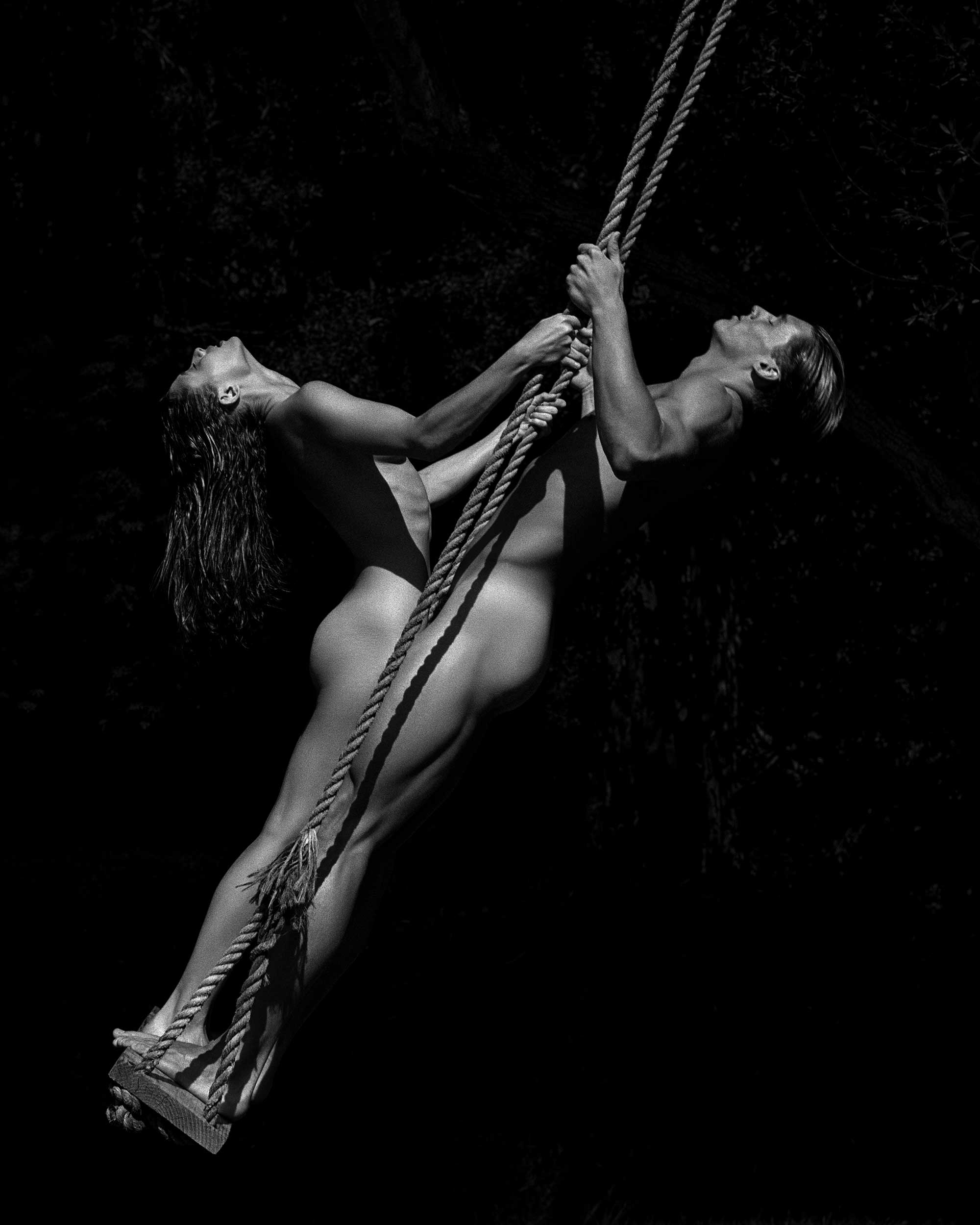

To see these images now is to recognize them from an earlier, non-art context, and to recall their impact: a stirring of sexuality, a seed of aspiration. I didn’t know he did this is something the curators—Nathaniel Kilcer, a creative director who has worked with Weber for decades, and Helena Musilová, director at GHMP—say they hear often. The first picture in the exhibition was one of those early Calvin Klein shots, from 1988, for the fragrance Obsession: A nude man facing a nude woman, both standing on a rope swing and arching their backs. Maybe you remember it from a magazine. Nearby was a wall-sized print of a nude Peter Johnson, the protagonist of Weber’s film Chop Suey (2001), and a portrait of four golden retrievers collared with signs that read “Dogs for Peace,” a still from Weber’s tribute to one of them, A Letter to True (2003). The 1990 music video he directed for the Pet Shop Boys’ “Being Boring” was projected behind that first room’s Gothic archway, sound on. At the end of the exhibition’s suggested route: the video for their “Se a vida é (That’s the Way Life Is)” (1996).

The embedded editorializing in Weber’s work served a challenge when curating the show, Kilcer told me. “So many times, you need the story to inform. In the fashion imagery, he is such a cinematic photographer, so it’s like you’re lifting these pictures out.” Though they were not as present in My Education, words—quotes, diary entries, lyrics, poetry—are usually everywhere in Weber’s work. Certainly, the choice of opening and closing numbers is not without intention. “I came across a cache of old photos,” begins “Being Boring,” a reminiscence of youth. It is also a song about death, written by singer Neil Tennant for a friend who suffered from AIDS in the ’80s.

To see these images now is to recognize them from an earlier, non-art context, and to recall their impact: a stirring of sexuality, a seed of aspiration.

What at first appears as pure joy is more accurately the tension between innocence and adulthood, life and its drive toward expiration. Haphazard collage is used as palimpsest, a way of seeing the dimensions of a moment—serious sentiment met with frolicking animals, just as, in life, a dog may sense despair and offer, bewilderingly, an expression like happiness. On a wall facing that first projection was Weber’s scribbled dedication “to my friends here,” listing first names of collaborators and subjects who attended the opening, mentioning “my dogs say Hi (Barking)” over a signature: “Bruce Weber + my wife Nan Bush.” (Yes: Commonly described as a preeminent gay artist, Weber has been happily married to a woman for nearly half a century.) Seeing this inscription facing the music video, I was reminded of Tennant’s repeated laments about publicly coming out, maybe best said in Hot Press: “I can’t see any reason to define gay people by their sexuality.”

Weber hears music in his head when he looks at photography. Irving Penn, he told me, is classical, but “in Broadway terms, he’s strictly George Gershwin.” Whereas Richard Avedon is more “Harold Arlen, you know, ‘Somewhere Over the Rainbow.’” And what would soundtrack Weber’s work? “I’d have to say, maybe, Chet Baker.”

No surprise there. Weber directed the Oscar-nominated documentary feature Let’s Get Lost (1988), which follows the heroin-addled jazz trumpeter and singer during his forlorn final months. Mention of the name sent Weber into a reverie, not about that intense, sustained, ’80s interaction but a time of initial discovery, in the early ’60s: “I thought, Oh, god, it would be so much fun to be that guy.” A funny thing to say about a man he essentially watched deteriorate, I think. I mentioned the videos from the exhibition. “I like the Pet Shop Boys, too,” he said, “because their music was so exciting, and I was really shy.”

This is a man who isn’t afraid to meet his idols—who meets them all the time. As a child, he was obsessed with Elizabeth Taylor. He later befriended her while she sat for him. A room in My Education is dedicated to his portraits of some artist heroes: Andrew Wyeth, Paul Bowles, Sheila Hicks, Joan Didion, Pedro Almodóvar, Jane Campion, Francis Ford Coppola, Purvis Young, Louise Bourgeois, Helmut Newton, Georgia O’Keeffe, Allen Ginsberg.

Other rooms displayed stars of film, fashion, music, sport, and society, many of whom Weber he counts as close friends. Always present, though, is a calculated distance between photographer and subject, including street-cast models and pets. Everyone poses, sometimes in a paper crown or on a pedestal, propped up with the dizzy angles of fandom or an unrequited crush.

Such meditations on idolatry are ironically situated within the circa mid-fourteenth-century Stone Bell House, part of Prague’s long history of iconoclasm. When I arrived and met the exhibition’s creative and executive producers, Milosh Harajda and Markéta Tomková, I asked why we’re here, of all places, instead of, say, Weber’s Miami Beach HQ during that city’s Art Basel week? The two took this on as a pet project, they said, suggesting that their city would be the perfect jumping-off point for an international tour. After the allegations, the lost commercial clients, and then the pandemic, the studio needed a soft place to land—somewhere everyone in their inner circle might visit for an opening but sheltered from the unforgiving art or fashion world stages.

Photograph by Noe DeWitt

Photograph by Noe DeWitt

That My Education premiered in a city defined for centuries by its anti-establishment preachers gives it a sheen of Gothic agnosticism. Weber’s work might pray at the altars of the Bible Belt and Appalachia—athletes, beauty queens, and purebreds—but a larger story weighs the value of such dedication, juxtaposing all that religion with other tragic icons, such as those in show business. Hang on to the fantasy, it says, because facing reality won’t be what brings salvation.

In January 2018, Weber responded to his situation via Instagram, denying all charges. “I have spent my career capturing the human spirit through photographs and am confident, that, in due time, the truth will prevail,” he wrote. His legal battles concerning the misconduct allegations ended in 2021, after one model’s claim was dropped and a lawsuit involving a joint complaint made by five others was settled out of court. At a time when many fashion photographers (Mario Testino, Greg Kadel, Patrick Demarchelier, David Bellemere, and Terry Richardson, to name a few) were being cut off by editors and brands due to accusations of inappropriate behavior on set, the mass cancellation prompted broader consideration of the industry itself. What sells, after all? Would modeling be forever changed with the advent of the intimacy coach? How much doting, on the part of a photographer, crosses a line into flirtation, or harassment?

Weber is soft-spoken, a white-bearded man with twinkling eyes. When we met, he was wearing a brown Carhartt canvas jacket over a denim Bode shirt, mentioning that the designer duo are his friends. He told stories he’s likely repeated many times, such as the one about when he and model Kate Moss visited an orphanage in Vietnam and had to pull themselves away from those poor smiling kids for their shoot, towing a tractor-sized trunk for a single John Galliano gown. It was Christmastime and he apologized for cutting our conversation short: He was already behind writing his holiday cards. I couldn’t quite bring myself to mention sex.

“If you asked him, he would say he is a gay man,” said Eva Lindemann-Sánchez, a film producer who has worked with Weber for decades. “But no one asks him. It is also true that he is married to a woman who he adores and greatly admires and respects and has been with for almost fifty years.” Kilcer added that one of Weber’s own adages says, “Photography is about having a crush. On a man, a woman—” Lindemann-Sánchez nodded. They said, in unison, “a dog.” I brought up the “queer artist” descriptor, to which Lindemann-Sánchez answered, “There’d be a part of him that would take ownership over that, but it would simultaneously surprise him.” “He leads with emotion,” Kilcer said. “He embraces the awkwardness of that, the disappointment that comes from that, the spontaneity, but also the vulnerability.”

“To answer the question,” Lindemann-Sánchez chimed in again, “he does not identify as a queer photographer. People want to put him there.”

Weber’s well-documented live-laugh-loving home life doesn’t totally contradict the raw sensuality seen in his portfolios of male nudes, such as the much-coveted photographs in the book Bear Pond (1990), shot around his and Bush’s home in the Adirondacks. More often, heteronormative tropes, such as Hamptons luncheons and movie-star romances, are intertwined with homoerotic scenes, suggesting a world in which these ideas live in harmony.

In a small theater attached to the coat room of the exhibition, a few of Weber’s shorts, including Backyard Movie (1991), played on a loop. Via handwriting and voiceover, we learn that as a child, Weber didn’t play sports, preferring to practice showtunes in his sister’s bedroom and snuggle with the family French poodle, Coquette. He recalls his mother asking him, “Which way are you swinging?”

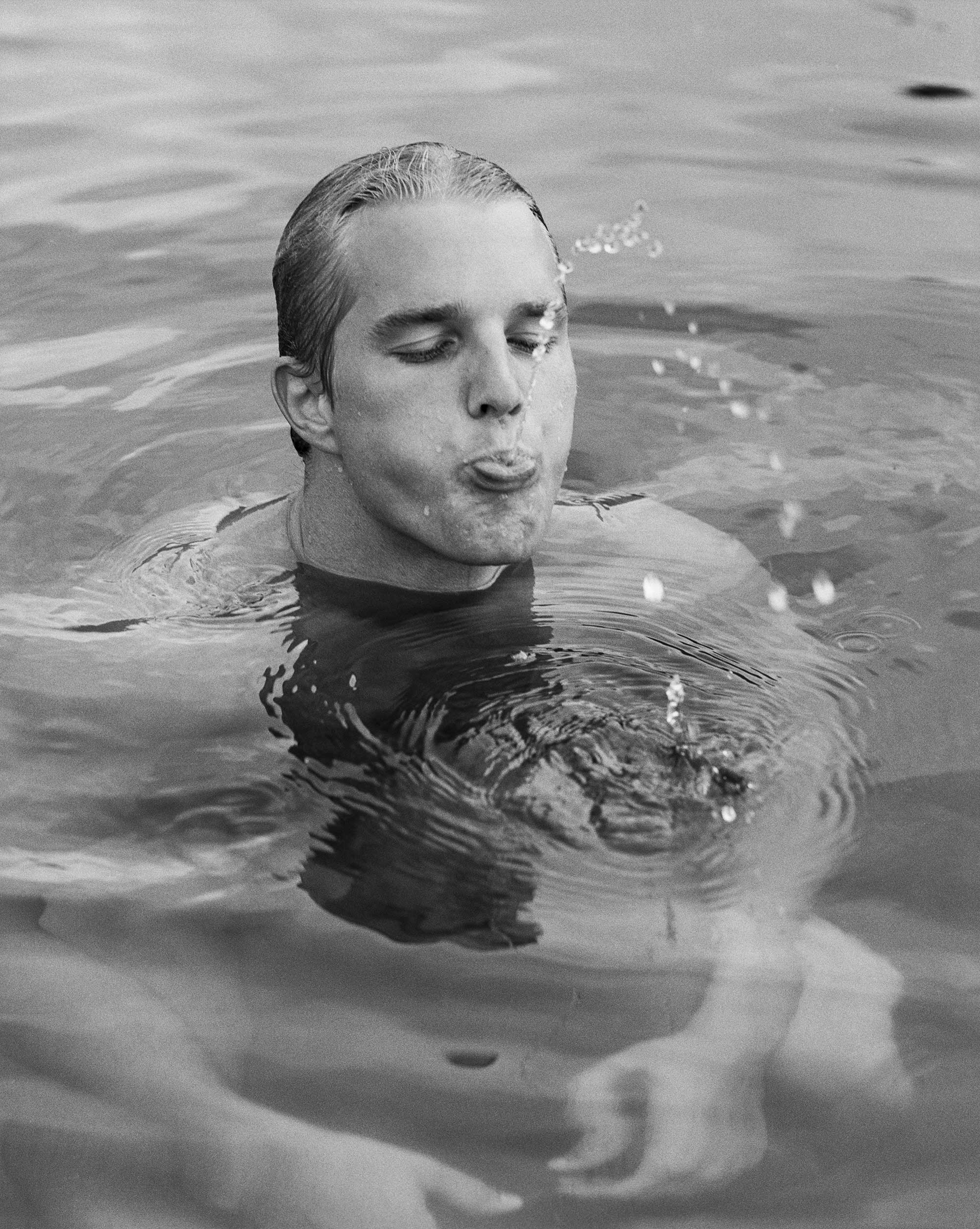

“I told her,” the text continues, overlayed on black-and-white home video clips spliced with a nude young man emerging from a swimming pool and dogs running on a beach, “that the night before I carried a drunken Tennessee Williams up the stairs of a restaurant and as I put him into a taxi he turned to me gently putting a hand to my cheek and just said ‘oh, beauty.’” The footage jumps into color, showing children walking through a flower garden. Animated handwriting details a trip to the famous gay bar Stonewall Inn, where a man asks young Weber to dance. Scared, he sits in a corner and watches the room morph into a salon of actors and authors. “Being lucky I can just close my eyes and transport myself to another time and place,” he writes. “A lot of people think having a big fantasy life is dangerous. That’s why people have tried to take it away from me.”

In Chop Suey, Weber invokes Clive Bell describing to Virginia Woolf the feeling of anticipating a visit from a friend. “That sense of longing was what I wanted to put in my early pictures of him,” Weber continued, referring to his muse Peter Johnson. “When I was filming Peter and his friends in the shower, I remembered myself at that age. In that fantasy, I would have been one of those kids, clowning around without a care in the world, but back in my hometown of Greensburg, Pennsylvania, it was a different story. I’d be swimming all day at the country club and my mom would tell me to shower and dress for dinner. I’d tell her I couldn’t, because the locker room would be too crowded at that hour. It seemed to me that every guy in the whole Midwest would be in that locker room, showering. We sometimes photograph things we can never be.”

Love is mostly projection, idealization. We revisit our first crushes for the rest of our lives, wherein unattainability was paramount. For a gay youth in the 1950s and ’60s, this exciting period of discovery is twisted with shame, the other side of which is yearning for a heterosexual lifestyle so extremely romantic it could counterbalance any natural lust for the socially unaccepted. Weber’s work has spurred intense desire, but it is essentially an exploration of that desire, the wanting and the wanting to want.

The first and only other time Weber had been to the Czech Republic was in 2000 for a Vanity Fair cover story with Heath Ledger, who was filming A Knight’s Tale and who later died from a drug overdose at age twenty-eight. Jeff Buckley, who, Weber reminds me, drowned in the Mississippi River at thirty, is featured in My Education as well, as is Stella Tennant, who committed suicide at fifty, and Dash Snow and River Phoenix, who overdosed and died at twenty-seven and twenty-three, respectively. I asked about youth and tragedy, as a theme.

All photographs © the artist

“I had amazing encounters with these people,” Weber said, the focus leaving his eyes. “They were so alive for me. I believed so much in what they thought, what they were doing, how much they loved doing things. They had that romance, that kind of honesty. Photographers and filmmakers are always trying to find that. Sometimes, if you look too hard, you’ll never find it, and it comes out as something else.” “People who are interesting defy the buckets you’re trying to put them in,” said Kilcer, of Weber. And Weber’s work rearticulates those very buckets: The impossible standards of masculinity and femininity, of innocence and stardom, the people who epitomize them. A room in My Education exclusively featured statuesque nude men, some printed as partitions and arrayed atop a mirrored floor like classical fountains. Gazing at an image of Madonna kissing her own reflection, one can almost hear the crowd’s hush that leaves a pop star lonely. Another room of documentary photography showed citizens in war-torn countries and post-industrial America. Inner-city kids, veterans, and orphans beam for the camera, just as the fashion models do.