Akinbode Akinbiyi, Passageways, Involuntary Narratives, and the Sound of Crowded Spaces, 2015–17

The first time I saw Akinbode Akinbiyi was in a little digital square. It was a documentary about his practice and he was peering down through his Rollei at a Johannesburg street. Then I met him at the LagosPhoto Festival where we exchanged few words, but found instant recognition. Years later, he was my assigned mentor for the Goethe-Institut Johannesburg Photographer’s Master Class. His advice has always been poetic and lyrical with a crystalline core of unflinching honesty, just like his images.

Rahima Gambo: When and how did your journey into photography begin?

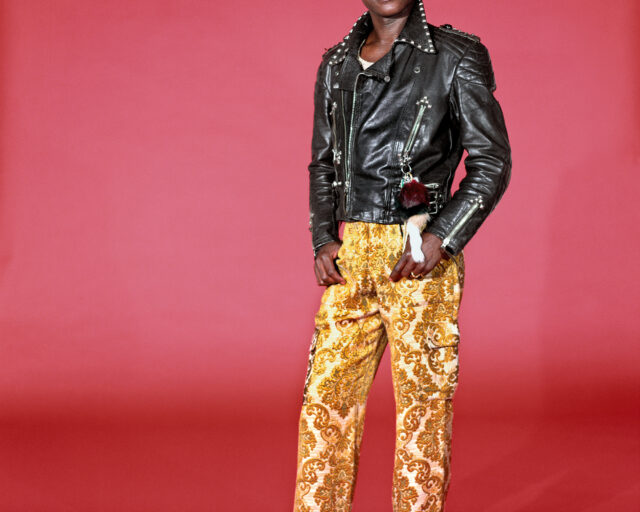

Akinbode Akinbiyi: It started in an uncertain, still-colonized Lagos of the 1950s. My parents were forging a path into what was then an uncertain future. This uncertainty made us—their four children—aware of our surroundings, looking, listening, trying to understand. My practice as a photographer started in the pages of National Geographic, the West African edition of Drum magazine, and the Black Photographers Annual. After university, I took up photography as a hobby but soon grew much more serious. It was very much a learning-by-doing process. I soon discovered the powerful work of Japanese post-Second World War photographers and then Latin American photographers. The photographers who struck me most deeply were those from the continent: David Goldblatt, Ernest Cole, J.D. ’Okhai Ojeikere, Peter Obey, and, somewhat later, Seydou Keïta, Malick Sidibé.

Gambo: Your projects seem mostly to dwell on urban Africa, yet you live in Berlin, Germany. Does geographical proximity matter in your practice and mentorship activities?

Akinbiyi: Proximity does matter, but it need not necessarily be physically close. What matters is being sincere and aware of the inner impulses that course through us all when making images. It is not the environment that determines the approach, but rather how you stand in relation to yourself and what you want to say, to see, to create. My approach to mentoring is to gently urge younger colleagues to hear their inner voices, see their inner eye, and take it from there. The location of teaching is of little importance.

Gambo: Can you describe the photography education landscape in Africa in the beginning of your career and how it compares to today?

Akinbiyi: In the early 1970s, there were few if any institutions devoted to photography. Art institutions focused on drawing, painting, and sculpture. Those who wanted to learn photography usually assisted established photographers or went abroad to recognized institutions. The Market Photo Workshop in Johannesburg, founded by David Goldblatt in the late 1980s, was one of the first photographic learning institutions on the continent and an influential one that has brought forth a wealth of articulate and incisive photographers ever since. Hence, one finds that South Africa, the leading economy on the continent, has a relative wealth of art institutions that today promote and teach photography. Internationally recognized South African photographers have had a synergic effect on their country and further afield. Other regions too have brought forth talent, such that today North, West, East, and Central Africa are on the map as much as South Africa, though oftentimes not in the number of recognized photographers. This is due to the uneven development in photography education and the many serious problems that beset many countries in Africa.

The powerful surge of the digitally mobile age has encouraged a willingness to photograph and record ubiquitous happenings, subsequently uploaded to various Internet sites. This has led to a kind of facile regard towards photography and being a photographer.

This one development, the easy access to photographic equipment and its even easier dissemination, has helped, and at the same time hindered, the development of photography on the continent. Helped, in that photography has become even more democratic, even more widespread than ever before. Hindered in the almost insurmountable number of images now produced, downloaded, viewed.

A careful scroll through these archives of downloaded visual data makes very apparent the superficiality of much that is produced. Clichéd images from a sensibility dulled by extreme overkill. However, a few resonate, give evidence of aspiring talent in the jungle of unending visualizations.

Gambo: Why did you begin to focus on developing photography education and mentorship in Africa?

Akinbiyi: One workshop led to the next until I was actively involved in establishing a network of teaching centers called “Centres of Learning for Photography in Africa” across the continent. The role model was the Market Photo Workshop in Johannesburg. The Goethe-Instituts in Lagos, Khartoum, and especially Johannesburg have been critical in this development. Johannesburg provided seed funding to get the whole program of Centres of Learning for Photography in Africa off the ground. The intention was to encourage young practitioners to get a formal photographic education based on a set curriculum and with the intention of becoming professionals.

Gambo: Can you describe your photography education and mentorship work in Sudan? How has it impacted the photography scene there?

Akinbiyi: Khartoum, Sudan, is a secret almost too precious to be mentioned. The city at the confluence of the two Niles—the White and the Blue Nile—is a like a jewel hidden in the tales of woe that so often come out of our continent. Due to the years of economic, and in many ways cultural, embargo, photography in Sudan was not particularly developed. In 2013, I took part in a series of workshops where participants were eager to learn. Their enthusiasm was a joy to experience, and in a very short time, the quality of work by these young aspirants leapt forward. Their work was exhibited at the 2016 Mugran Foto Week and in two rooms at the National Museum in Sudan.

All photographs courtesy the artist

Gambo: What is the future for young African emerging photographers?

Akinbiyi: The future is bright. Still, a major challenge is avoiding the pitfalls of being too attuned to the Internet, to the ready-made images that constantly flood screens and social media sites. Too many of these images are like a visual version of highly toxic fast food. The same Internet does however afford an insight into serious photography, if used and applied with a sense of purpose. This brings up the vexed question of how many have this diligence and sense of purpose, how many are so passionate about photography as to want to seek out past masters and their techniques and motivations. Opportunities are few and the Centres of Learning for Photography in Africa are still in the early stages. Some participants cannot afford the low fees being charged and workshops are infrequent. One constant weakness I see is the lack of research so many emerging photographers bring to their chosen subject matter. Almost as if they enter blindly into the foray of going out there and taking, making images.

Gambo: Can you tell us a little bit about your work at documenta 14 in Athens and Kassel?

Akinbiyi: The work is very much about spirituality, how it manifests physically in our daily wanderings and doings, so quietly and often unnoticed, that we are often surprised when it gently comes through.

This article is part of a series produced in collaboration with Contemporary And (C&) – Platform for International Art from African Perspectives.

See more in Aperture Issue 227, “Platform Africa.”