Carmen Winant’s Powerful Homage to Abortion Care Workers

Assembling over two thousand photographs of daily life in reproductive health clinics, Winant centers routine labor as an essential act of care.

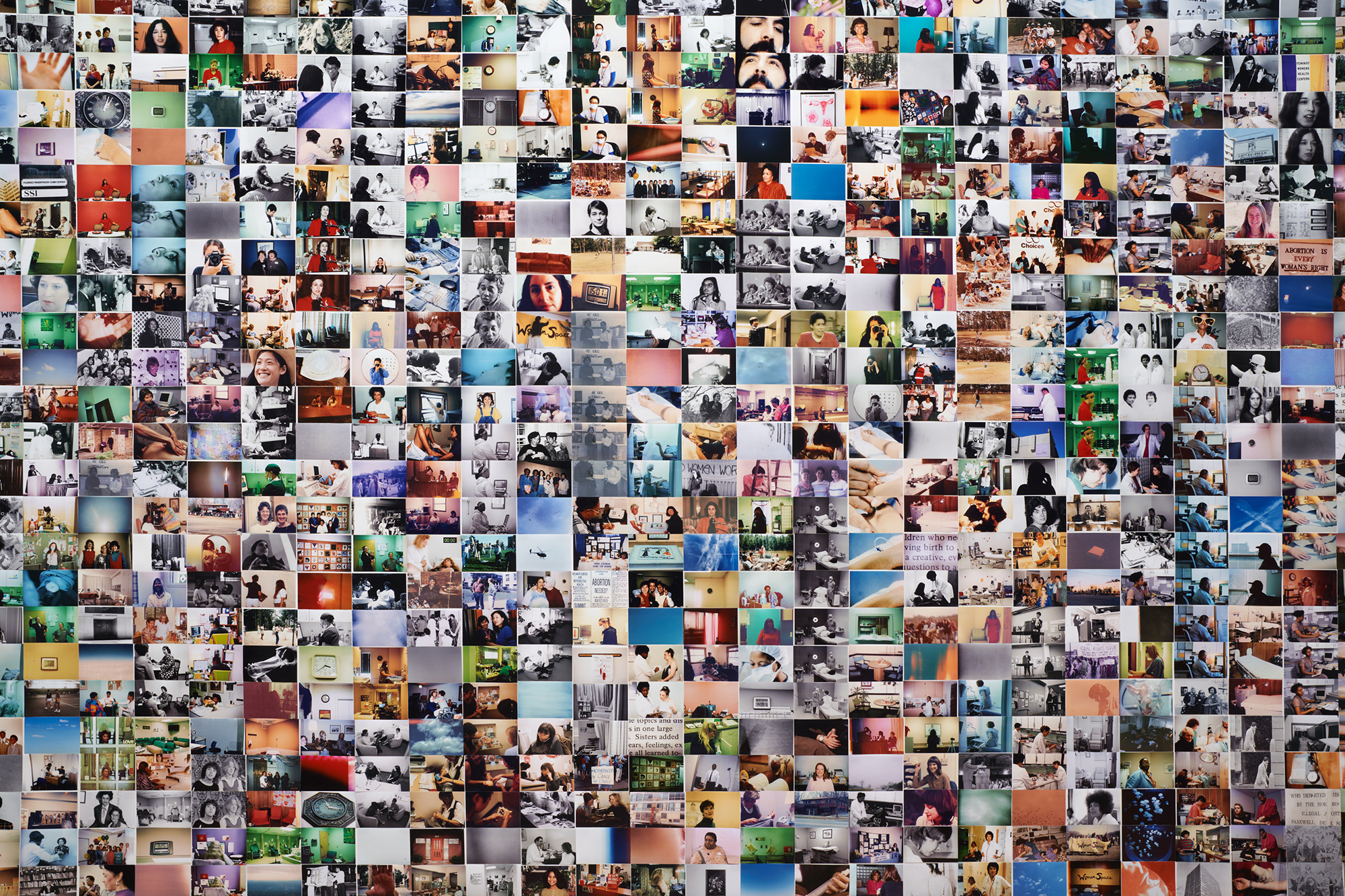

Carmen Winant, The Last Safe Abortion, 2023

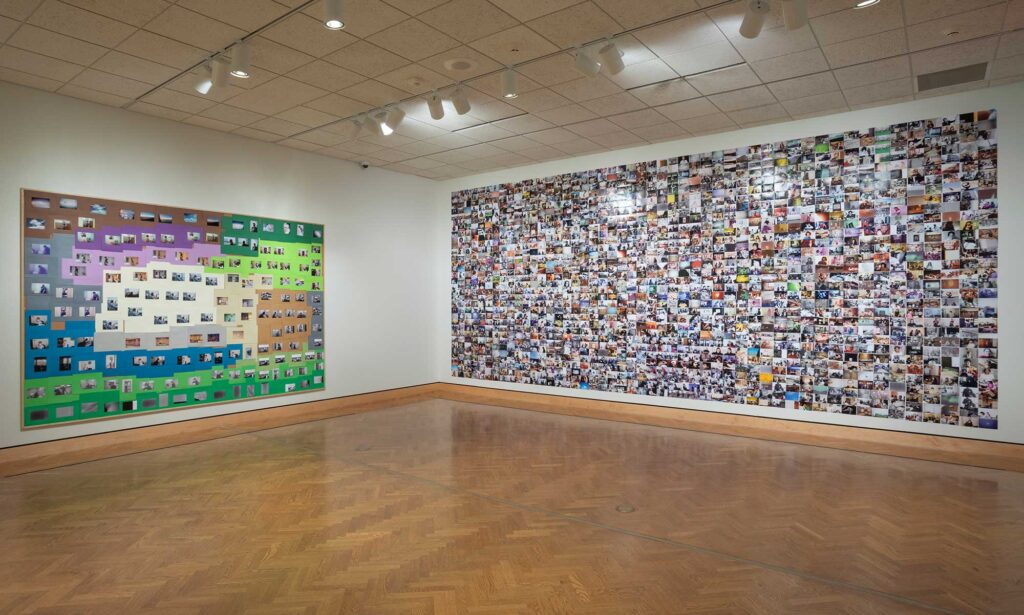

Carmen Winant’s The Last Safe Abortion claims an entire wall at the 2024 Whitney Biennial, a floor-to-ceiling sweep of images gathered and created in partnership with the health care workers it honors. Composed of nearly 2,500 individual photographs, each capturing the daily routines of abortion care workers, The Last Safe Abortion is a monumental homage to feminist health care. Striking in scale and precise in its ordering of each 4-by-6 color print, The Last Safe Abortion compels viewers to move closer and walk alongside it to absorb the smallest elements of the assemblage. The conceptual meticulousness of the whole belies the everydayness of the images within the grid, and that is the point: Each snapshot is, as Winant puts it, “an ordinary drugstore print” of the office work performed in clinics across the midwestern United States. These seemingly unremarkable images of people answering phones, entering data, filing paperwork, and completing mandatory trainings are a deliberate de-escalation of the visuals associated with abortion care by its opponents; instead, Winant places our attention upon the routine, even mundane, labor performed by providers as they care for their clients and each other.

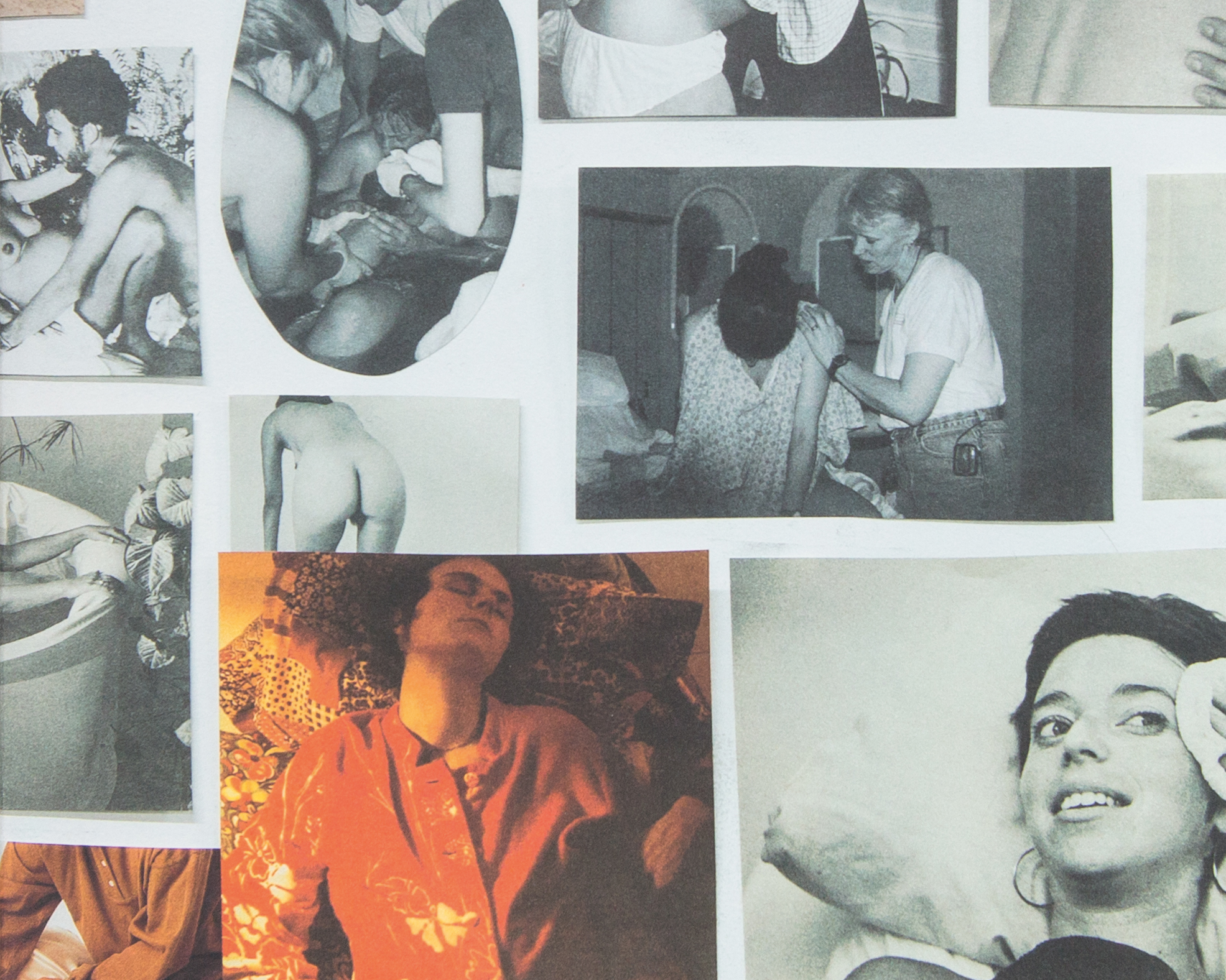

For the better part of the last decade, Winant has drawn inspiration from and within networks of care, considering their associations with radical social movements. When her landmark installation My Birth opened at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 2018, Winant put feminist health care at the forefront of the museum world’s public conversation; in many ways, The Last Safe Abortion continues that work, albeit in a newly charged political and cultural landscape. (Winant’s book about the project, published by SPBH Editions and MACK, was recently honored by Les Rencontres d’Arles, the French photography festival.) With recent United States Supreme Court decisions impacting the lives of millions of Americans—including Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which dismantled federal rights to abortion care in June 2022, and the decision in June 2024 to uphold national access to mifepristone, a pill used in medication abortion—Winant’s project is ever more resonant. We recently spoke together about the origins of The Last Safe Abortion, a project conceived during the pandemic for presentation at the Minneapolis Institute of Art in the fall of 2023, and how she wants the work to continue in the months and years ahead.

Casey Riley: Why don’t we begin by talking about the origins of the project and maybe sharing a little bit about its evolution. We first started our conversation early in 2019.

Carmen Winant: Another lifetime ago! Initially, we had just a series of open-ended phone conversations. It never felt like you had an agenda; we were just getting to know one another. We had so much affinity. Not just our shared political commitments, but also the way we held conversations, remember? We talked that way on and off for at least six or eight months before surfacing the idea of doing a project together. Do I have that timeline right?

Riley: Absolutely. The overall process for us was about four years.

Winant: There were different iterations of what the show was going to be during that extended period. We had the luxury of time, and to be responsive to the world as it was shifting around us.

Riley: It really was an iterative process. You started off thinking that you wanted to use the feminist obituaries you were collecting, to experiment with them materially in the studio.

Winant: In 2019, I was still coming off the experience of showing My Birth (2018) at MoMA, an installation curated by Lucy Gallun. That had been such a profound experience. But, based on the kinds of invitations that followed, I was worried about being pigeonholed as an artist who exclusively made work about biological birth. In fact, I considered My Birth to be a part of a larger project that engaged the sociality of feminist healthcare coalitions—of how feminists build kin networks. Centering my obituary collection felt like a new way to do that. I had hundreds of them then; I must have thousands now.

Riley: I’m sure Luke [Stettner, Winant’s partner] loves that.

Winant: Yes, especially when they spill over from my studio, which is in the attached garage, to the house and onto the dining room table.

Riley: “What’s that?” “That’s just mommy’s death pile.”

Winant: I can’t help myself! You and I talked through that process for months. You were so generous in your time and openness, especially as it wasn’t coming together as I’d hoped. We tried to wrestle with it together, and I never felt like I had to hide anything that wasn’t working from you. In the end I didn’t work with those obits, but the process yielded the project that we did work on together that centered abortion care workers and advocates, as so many of the feminist obituaries were about women who crusaded for reproductive justice. It was a matter of trusting the process, and its sort of unexpected evolution.

Riley: Why don’t you describe the work that resulted for folks who have not attended the Whitney Biennial or seen the show at the Minneapolis Institute of Art?

Winant: At its most basic, material level, it is a project made up of thousands of small prints, almost all of them 4×6 lab prints. There are several thousand in the show. They are a combination of archival photographs drawn from abortion clinics and special collections, as well as photographs that I made in some of those same clinics, decades later. They are intended to be read together, across geographical time and place.

Riley: Can you talk about the largest work in the MIA exhibition, which also traveled to the Biennial, The Last Safe Abortion? Do you refer to it as an assemblage?

Winant: I am open to any language. That work, in the Biennial iteration, holds about 2,500 4-by-6-inch prints. The kind of prints you get at the drug store in paper envelopes, which is in fact the way I found most of the pictures in the clinics. They largely come from across the Midwest and South, two areas particularly vulnerable to abortion restriction. They represent clinics in Nebraska, Ohio, Iowa, Illinois, Minnesota, Georgia, Texas, Kansas, New York, and North Dakota.

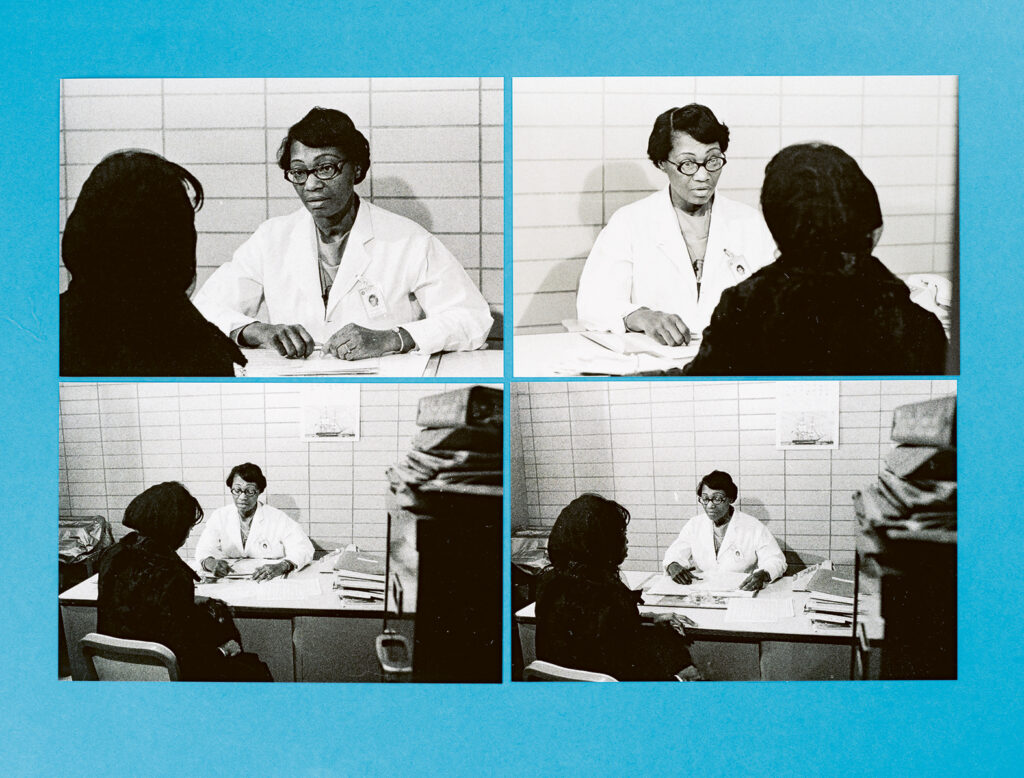

Riley: I’m curious about the way in which these prints represent work. The pictures show folks getting blood pressure tests, picking up prescriptions, celebrating office anniversaries, going through trainings, and answering phones. So many pictures of workers answering the phones!

Winant: Yes, the project increasingly came to be about their labor—and the project of picturing labor—as I went. I am interested in that problem: how to represent the fundamentally un-photographic acts that you mentioned, like answering the hotline, which are also the most essential and lifesaving. And I think you are also driving at my strategy of sort of “laboring” the artwork itself. I want to reiterate a sense of work in its making. This is not to equate my labor as an artist with the labor in the clinic, but rather to use one to point to the other, for all the meaning in its daily and repetitive tasks.

Riley: How did you gain access to these pictures? We’ve spoken a lot about the value of building intergenerational friendships in and through this process.

Winant: Yes, thanks for bringing that up. This is so hard to talk about or share in a demonstrative way, as it’s all rather interpersonal. This is the great gift of The Last Safe Abortion, and in some way, its real yield: building relationships with the women who have done this work for decades, often from before I was born, in 1983. The first time I meet with a clinic staffer or director, I never have my camera or scanner on me. Establishing trust is always a delicate process, but nowhere more than in the abortion clinic, where staffers’ physical safety is under daily threat and patient’s privacy is of the utmost concern. I am always telling students who are interested in working this way that it is so much more rewarding to enter these spaces, and these relationships, without any transactional expectations. In other words, if I were to enter the clinic or the early phone call with the idea of “what can I get from this?,” all hope would already be lost for me. I would be missing the point, and the larger opportunity. Getting to know the people in this work—who are themselves the subject of the project—is the point. Not a means to an end.

Riley: Right. You often refer to these folks as collaborators, not subjects.

Winant: It is an important distinction to make. We share the same goal: to normalize abortion care. In this way, the staffers were totally hip to the project as I was making it. They understood the way in which the pictures were to function as a political tool rather than as documentary.

Riley: Did you come to see the abortion care workers themselves as the protagonists?

Winant: I often make the same mistake at the start of a project, and that is to take a 30,000-foot, ideological approach. But, as the women on the ground have so smartly put it to me over the years: There is no feminism without feminists, no reproductive healthcare without reproductive healthcare workers. In other words, it is people who make it go. Hour in and hour out. This is the truth, but it also carries a political message: Abortion isn’t a concept or a political cudgel; it is a profoundly human experience.

Riley: This is deepened by the fact that the women who are in the photographs—doing pap smears and teaching sex-ed classes and so forth—are also so often the ones behind the camera, as you are also drawing from their archives.

Winant: Totally. They’re in the pictures, they made the pictures, they worked with me to facilitate the pictures. A feminist approach to photography if there ever was one, all this shared authorship.

Riley: And they continued to work with you after you had the pictures you were planning to use.

Winant: Yes, about a dozen women gave me hours and hours of their time to help me and my wonderful assistant Miranda identify the people in those pictures. We went image by image. Who was that person? Did they remember her last name? What is her email address or phone number? And so on. This was a great gift, and demonstrative of their larger investment and goodwill.

Riley: Let’s pivot a little, and talk about your relationship to lens-based photography, and making pictures.

Winant: I often find myself in the position of reminding people of this, that I am technically trained as a photographer! I spent many years making my own pictures and feel, maybe defensively, that I need to stake a claim. My practice functions still entirely within that framework—the history, materiality, and lexicon of photography. Though I will say that, even as a young person and an undergrad at UCLA, I was never that interested in making big, beautiful, singular images. This is not a value judgment—I love other people’s pictures that function that way. I just remember struggling with the process of editing on contact sheets. I always felt like, why can’t I have them all? It took me years to figure out how to have them all, to accept that as a way of operating with photography.

Riley: This project originated with other people’s photographs in a way that was fresh for you.

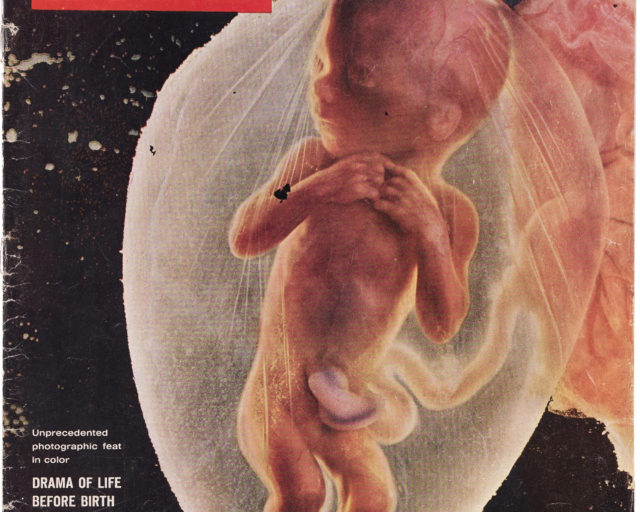

Winant: That is really true. The foundation for this project was slowly being built up in me for years, and somewhat unconsciously. I am certainly not the first person to note the strategy of the anti-choice movement to use—to really weaponize—pictures as ideological warfare. They have been doing this in an effective, streamlined way since the early 1970s. It is so deep and so familiar that I think sometimes we cease to recognize it as stratagem at all. Because I live in the Midwest and work on a huge university campus, I see the antis’ camp set up, always with large, gory photographs. In fact, I often have to walk directly around it to teach classes in photography (our shared medium!). This connection started to feel less and less abstract. I started to wonder about the absence of pictures in our movement. Why was that? What would they look like? As you and I discussed often—what is the visuality of abortion care?

Riley: The nature of the photographs can change over time, too.

Winant: Yes. I’ve shared with you that the photograph of Gerri Santoro, dead in the fetal position on a dirty motel floor after a botched abortion, has been burned into my mind since I first saw it as a teenager. That image, which appeared in every print edition of Our Bodies, Ourselves until the early aughts, really did its work; it haunts me still. I understand, in other words, why agonized pictures were needed to meet an agonized time. But I was born in the ’80s, as I said, into an abortion-safe world. When I got an abortion in 2017, between the births of my two kids, it was legal and efficient; I didn’t die, I wasn’t sterilized, I didn’t bleed out alone. I wanted pictures that could convey abortion care as regular and unsensational in that same way.

Riley: This project has its roots in Midwest, where we both live, and has since traveled eastward for the Biennial. Can you talk about the importance of doing a project that is tied to the Midwest? And then maybe the significance of having it in New York, at the Whitney? I’m curious, as abortion access has become so regionally specific, how moving the work affects you, and it.

Winant: Getting to make a project in the Midwest, about the Midwest, for an institution in the Midwest was a first for me. I am from Philly, as you know, but have lived in Ohio now for ten years; I can’t tell the number of visits I have done with curators on the coast who express profound surprise that I don’t live on one of the coasts, or press me for the ways in which I think that has posed professional challenges. Needless to say, access to reproductive healthcare is increasingly limited here, and there are large swaths of this region that are abortion deserts. You live in an abortion haven in Minnesota; Illinois and Michigan are two others. We are hanging on for dear life here in Ohio, where there has been incredible organizing. Representing the decades-long struggle for access in this region, and all the feminist healthcare workers in that struggle, was meaningful. I love the idea that those women could see themselves in a museum. That makes my heart sing.

As for moving to New York, you know, it is interesting: the show is following the same path that women made in a pre-Roe world to get legal abortions, from Ohio to New York. There was a whole network in place, and even abortion funds (before we called them that) to travel. I am thrilled that my work is in the Biennial, of course, where it can be seen by so many people. The idea with it—with any advocacy work—is to reach as many eyeballs as possible. The message doesn’t change in this way, it only swells.

Riley: Do you consider The Last Safe Abortion to be a monument?

Winant: I often refer to it, rather openly, as an installation—something that a viewer can enter, and that absorbs their peripheral vision. Sometimes I will call it a photographic quilt or tapestry. I like those words because they refer to the labor involved, because they feel more feminized. I like the idea of a tapestry as something at once decorative and functional, designed to hold all the heat in.

Riley: Do you object to “monument” because it feels too masculinized?

Winant: Maybe so. Maybe I need to harness it for that reason?

All works courtesy the artist

Riley: A monument invariably has something to do with power. That can go rogue, can be unfixed. Something to consider. And perhaps to claim. Let’s end on a note about how you see your role in what you often refer to as “the struggle.” In other words, the network of folks who are organizing for reproductive rights.

Winant: This is a hard question for me to answer. There are so many people who are doing such impactful work in this area, in this region and beyond. Their refusal to submit to despair, and their bravery and resilience, is truly heroic to me. At the same time that we were working on our project, folks in Ohio organized on the ground to put abortion access on the ballot, and eventually to enshrine abortion into our state constitution electorally.

In some ways, what I think you are also asking is: What can art do? I wrestle with this in big ways. Sometimes I feel that if I were a braver person, I would be an activist. But I was buoyed by the clinic staffers I came to know during this project, who continued to affirm my work back to me even as I was tripping all over myself, fearing that I was in their way. I still remember Eliza, the clinic director at Whole Woman’s health in Minnesota, telling me, “Carmen, there are many ways to be in the work.” That galvanized me. It was a reminder that coalitions, by definition, need many kinds of people offering many kinds of contributions.

The Whitney Biennial 2024: Even Better Than the Real Thing is on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, through August 11, 2024.