Caroline Tompkins Explores the Territory between Fear and Desire

In a book pairing eroticism with horror, the photographer bluntly foregrounds the psychic agitation that many people associate with arousal.

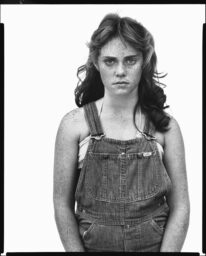

Caroline Tompkins, from the book Bedfellow (Palm Studios, 2022)

It’s intoxicating to be desired and cared for, even when that care is ruinous. In the introduction to her new book, Bedfellow, the photographer Caroline Tompkins describes a disquieting dream that came to her while in bed with an abusive former partner. “While we were together,” she writes, “I’d dream that I was covered in leeches.” In her vision, wet-looking, wiggling worms blanketed her smooth skin and sucked at her body. While Tompkins was involved with this man, he would break into her apartment when she was out of town and send her photos of its interior. He stalked her friends and threatened to kill himself if she ever left.

Pondering their relationship, Tompkins writes unflinchingly about her response to this controlling behavior. “I became comfortable being violated,” she says in the book’s introduction, recalling how she would text him back and sleep with him despite the abuse, “and I was always so, so sorry.” The leeches started appearing in her dreams near the end of their relationship. In Bedfellow, she reflects on the motif: “To dream of leeches is to understand that something is taking the vigor out of you.”

Years later, Tompkins decided to yank that dream out of her mind and turn it into a photograph. She researched leech therapy—a bloodletting practice in which therapists strategically place leeches on a client’s body—and ordered six medium medicinal leeches on leech.com. A friend offered up his body for the photograph, and she arranged him on her own bed in Queens before carefully setting the leeches on his skin.

The resulting photograph is one of the most striking and disturbing images in Tompkins’s new book. In the picture, an anonymous young man (we see only his torso) reclines on wrinkled blue sheets while three fat leeches sit, curled in a pool of blood, on his stomach. One of the worms rears up, its body gorged, slimy, and alarmingly animate. Only after we’ve noted the leeches do we realize that the man has his hand down the front of his pants.

In Bedfellow (Palm Studios, 2022), Tompkins explores the shadowy territory where fear and desire overlap. As in her leech photograph, where she pairs eroticism with horror, Tompkins bluntly foregrounds the psychic agitation that many people have learned to associate with arousal. In a conversation with the photographer this past fall, I asked about the image and her decision to have her subject touch himself. “That’s the last picture I made for the book,” she said slowly, “and I was after a confusing image.” She knew instinctively that the photograph needed a sexual component to feel complete. “It felt like it would end the circle,” she explained. She wanted to symbolically close the loop on a man who had manipulated her and scared her—but whom she desired nonetheless.

What happens to your understanding of sex when your early experiences of love and lust are tied to unease and anxiety?

For many young people, especially women, our earliest dialogues about sex are nested in conversations about danger. Is it any surprise, then, that we learn to associate one with the other? Bedfellow approaches an uncomfortable question: What happens to your understanding of sex when your early experiences of love and lust are tied to unease and anxiety? How do these experiences define identity? At what point do we begin to associate panic with anticipation? Fear and excitement feel deceptively similar in the body: your brain is shaking every tree and lighting fire to the ground.

Cultural reckonings like #MeToo made it clear that women tiptoe through minefields when they meet men at bars, through friends, at work. Approximately eight out of ten acts of sexual violence are committed by an acquaintance. More than a third are committed by a current or former partner.

As subjects, fear and sex have been present in Tompkins’s photography since art school. After moving to New York from Ohio in 2011, Tompkins was catcalled on a daily basis—a new experience. Rather than shouting back, she chose to respond through her photography. In the resulting series, Hey Baby (2011–14), she photographed the men who made her uncomfortable. Some of the catcallers shied away from the camera; others posed defiantly. That series, with its themes of transgression, aggression, and the male gaze, was a clear precursor to Bedfellow.

Most pages in Bedfellow pluck at the viewer uncomfortably, and though the source of the discomfort isn’t immediately clear, its generator is the body. Although it inspires endless fantasies, the naked body is often an awkward thing, with its jutting bones, tangled chest hair, and dry, scaly skin. Tompkins’s photography pokes at the male body in particular. Her interest lies in examining contemporary presentations of masculinity, both gentle and antagonistic. One image, a portrait of a man with a thick, curling beard and a small child, takes male tenderness as its focus. The adult in that image is imposing—he has a heavy chain tattooed around his neck and thick black wraps around one wrist—but he gently curls his lips as he kisses the kid’s cheek. Other images present a menacing vision of masculinity, as in the photograph of a bright blue, veiny scrotum dangling from a truck’s trailer hitch, or the image featuring a thin, naked man with serious eyes who licks his upper lip, his erect penis on full display.

Courtesy the artist

Many of the photographs in Bedfellow would seem innocuous were it not for the perplexing discomfort that wiggles at the back of the viewer’s brain, and Tompkins’s best images are often her most subtle. A deeply sensitive photographer, she has the impressive ability to assess her surroundings and pinpoint the moment her contentment falters, like spotting a snarl in the weft. Bedfellow is at its strongest when it scratches at the porous boundary between arousal and discomfort. Years ago, Tompkins attended a nudist festival and was surprised by the level of anxiety she felt in that space. She was surrounded by nakedness and sensuality, but she couldn’t quell the alarm bells in her mind. “I became really interested in how those reactions are two sides of the same coin,” she told me. “They’re two experiences that we hold at the same time, and to me, that felt like a truer picture of desire.”

Caroline Tompkins’s Bedfellow was published by Palm Studios in 2022.