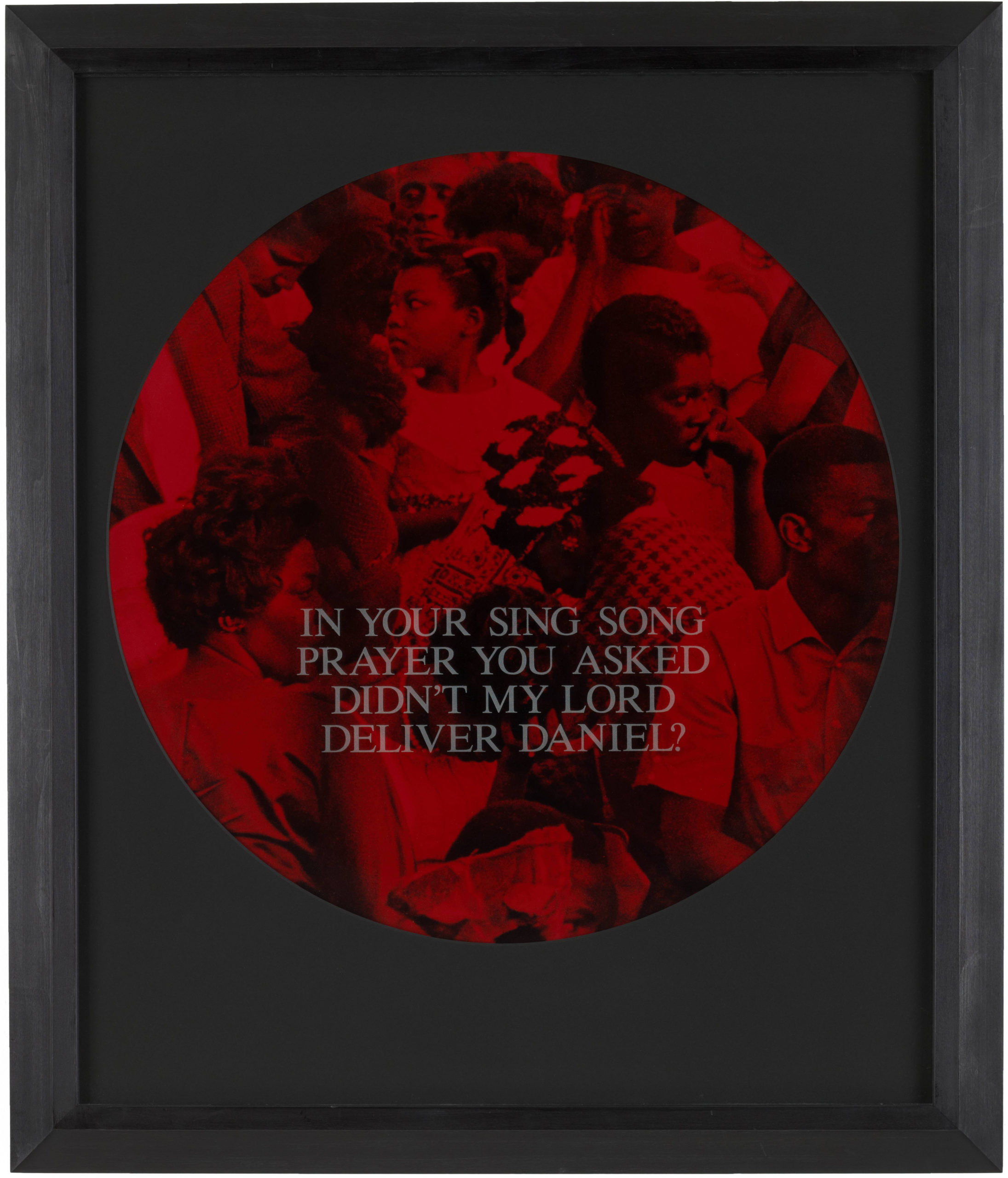

Carrie Mae Weems, In Your Sing Song Prayer You Asked Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel?, 1995–96

I sliced a watermelon open across its belly last summer and gasped, as the red flesh and black seeds resembled bodies inside the barracoon. When I go to the nation’s edge and put my feet into the shore of the Atlantic, I think of women throwing their babies overboard to be set free by the water, and the crashing waves turn to screams. When I ask my grandmother about her time on the cotton plantations of Louisiana, she rolls her eyes: “Here she go remembering again.”

A “land condemned to forgetfulness” is what the writer Eduardo Galeano once called America. Forget where you come from, forget your languages, forget your rituals, religions, homeland. Forget centuries of enslaved labor. But it’s all I can think about. To be Black in America often means that your history has been deliberately withheld, and the fragments that remain have been reframed to veil the unconscionable terrors that built the foundation of this nation. Conceptual artist Carrie Mae Weems has taken these fragments to construct a narrative that reckons with this somber history and draws a straight line to contemporary racialized norms in her photographic series From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried (1995–96), currently on view at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

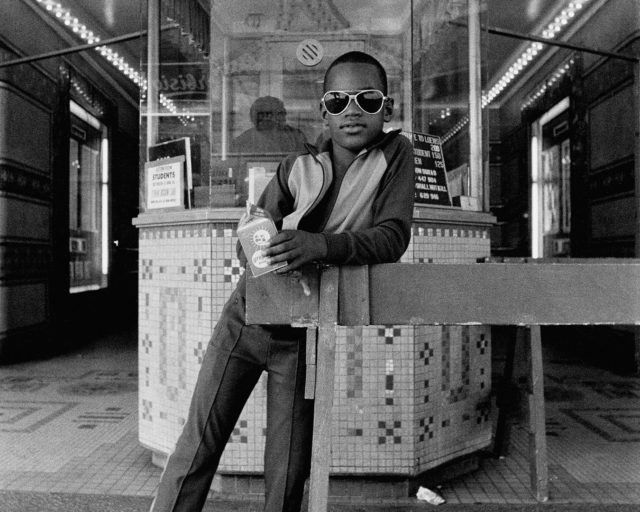

Photograph by Denis Doorly

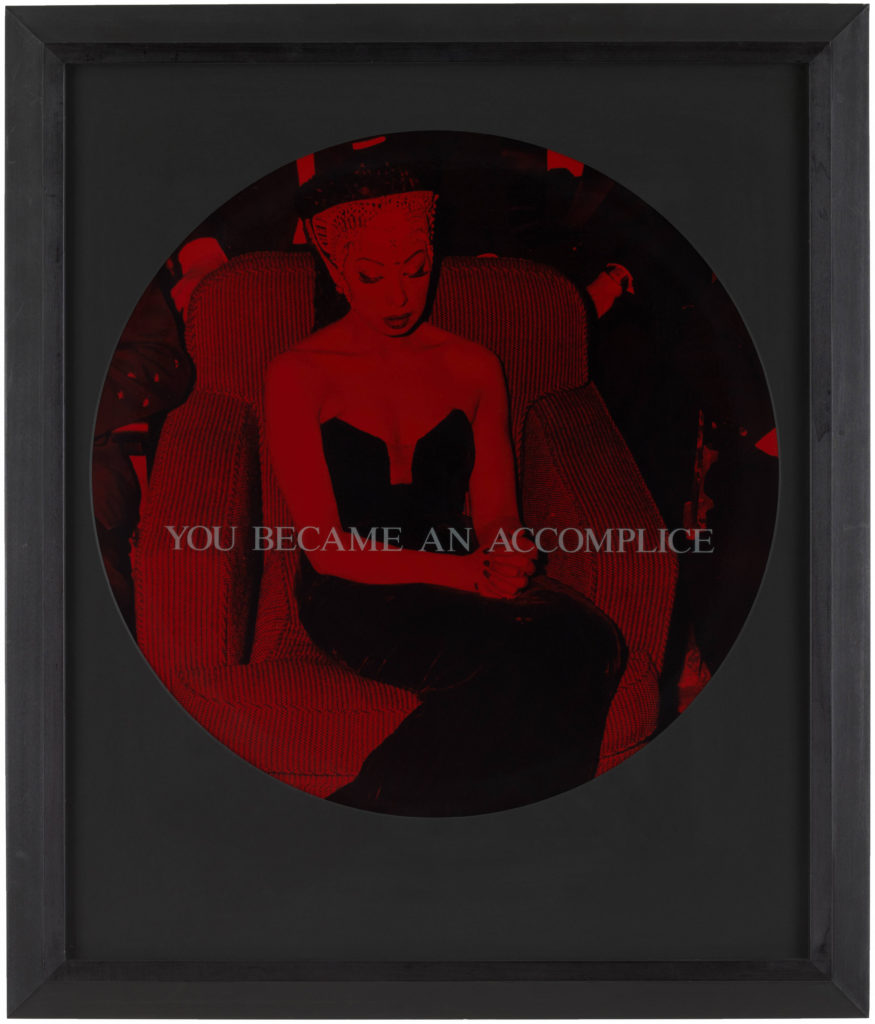

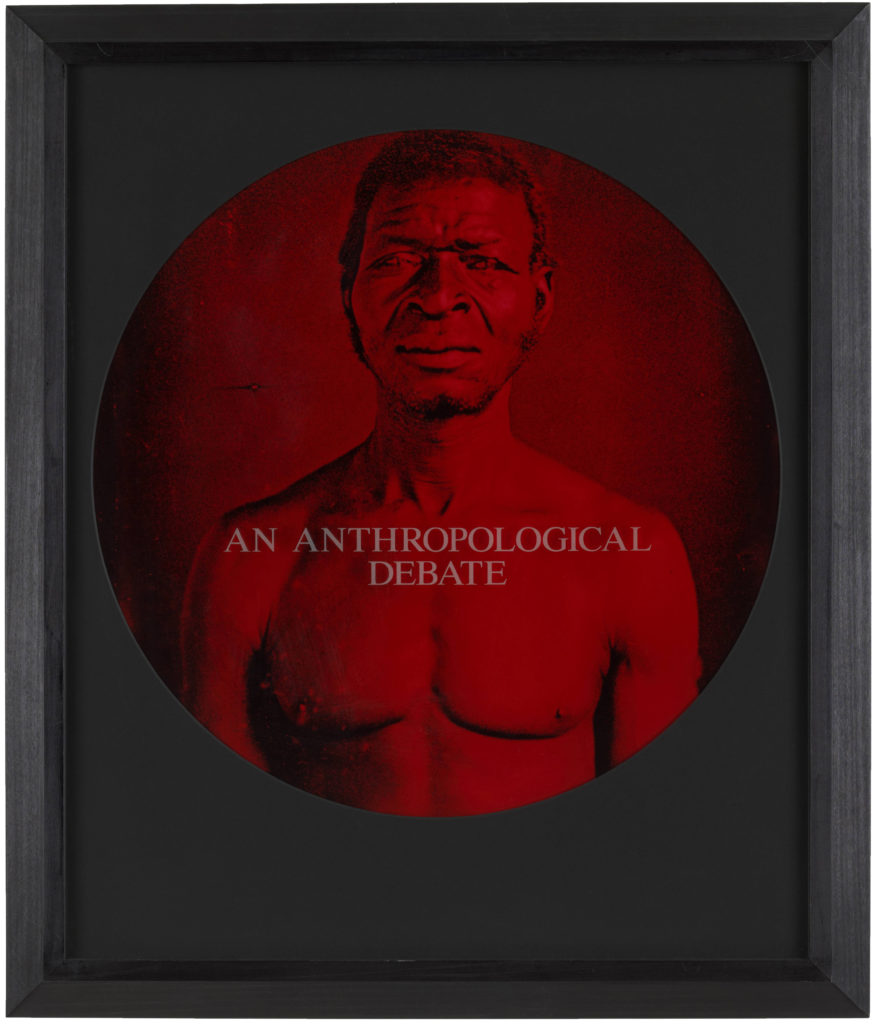

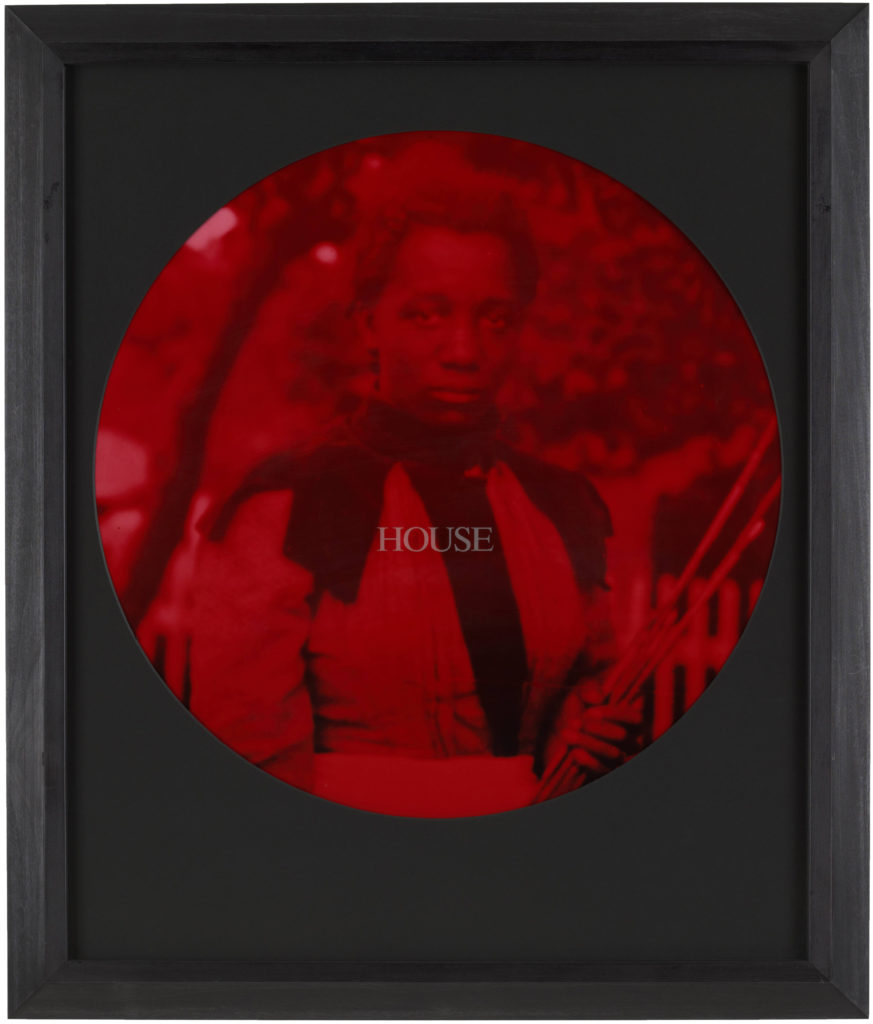

Thirty-three images, a divine number—including four enlarged daguerreotypes of enslaved men and women captured in 1850 by Joseph T. Zealy, produced in the name of eugenics by Harvard University scientist Louis Agassiz, and archived at Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnography. Weems’s series was originally commissioned in 1994 by the J. Paul Getty Museum for an exhibition called Hidden Witness. The Zealy daguerreotypes and other portraits of unnamed souls from the 1850s are situated alongside more contemporary images, like Garry Winogrand’s Central Park Zoo (1967), depicting a white woman and a Black man holding monkeys (the presumed outcome of miscegenation’s one-drop rule) and, furthermore, just how insignificant progress has been. But what of the Black woman whose hair is tied down, but her legs lie wide open on the bed, her hand and the lens positioned in between? In the way she holds her mouth, slightly turned up but not quite a smile, you can see that the subject has subverted her oppression to power as Black Venus, both despised and hypersexualized: You Became Playmate to the Patriarch. Weems’s prose bites and stings. I look away quickly, in fear of further demeaning Black Venus, in fear of seeing myself in her.

Weems, the sixty-seven-year-old Portland, Oregon–born artist-curator, has long been a genius—even before she was named a MacArthur Fellow in 2013, and before she became the first Black woman artist to have a retrospective at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in 2014. She has been most notably characterized by the care and complexity that she extends to her subjects, and also to her peers and colleagues, such as the photographer, curator, and historian Deborah Willis, whom Weems invited to Los Angeles for her first professional exhibition. HBO’s recent documentary film Black Art: In the Absence of Light (2021), directed by Sam Pollard, highlights the dynamic community formed with the Studio Museum in Harlem as its nucleus and home base, and the insistence on Black artists to reshape the ways that the world sees. To reclaim and expand the limiting views projected onto the Black body. Weems is featured saying what many have recognized: “Most of the primary cultural institutions have been behind.”

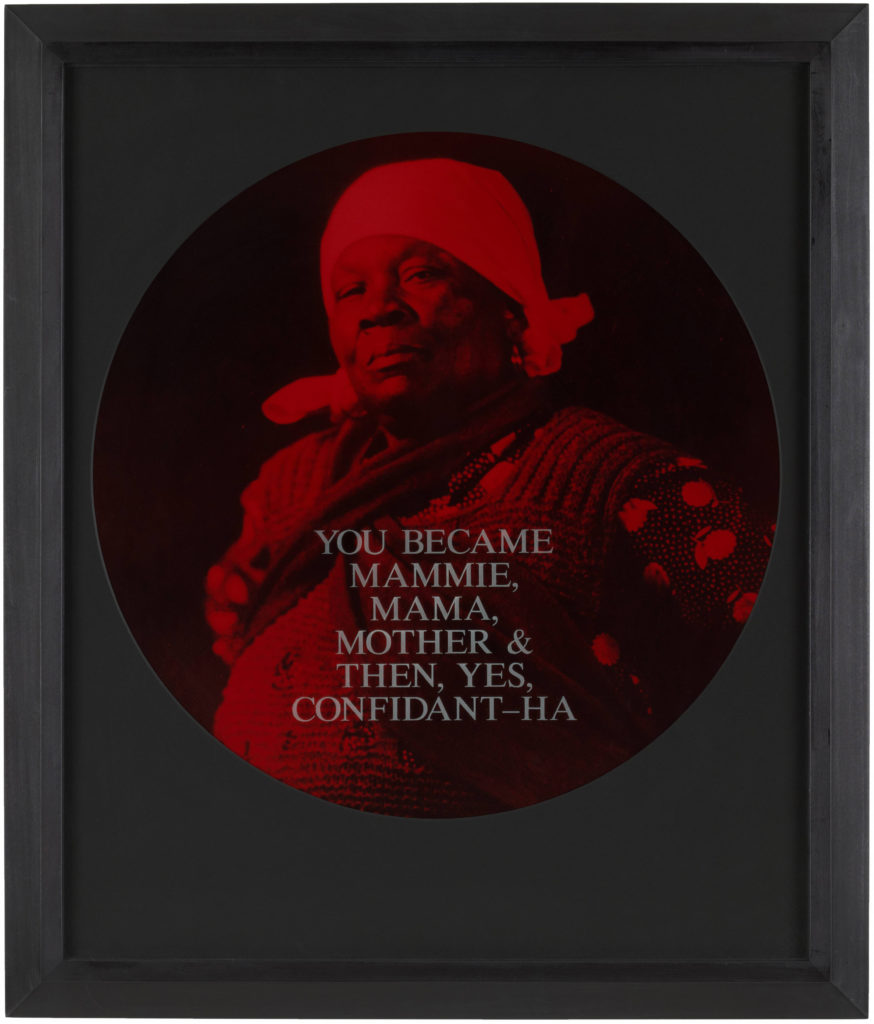

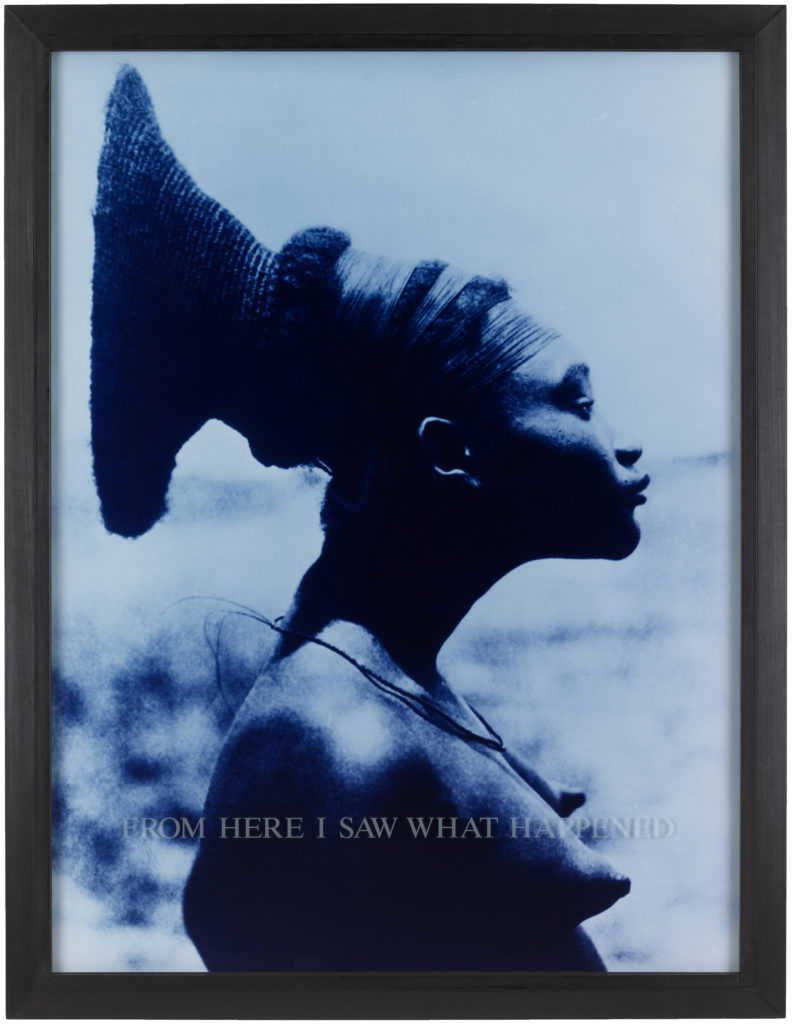

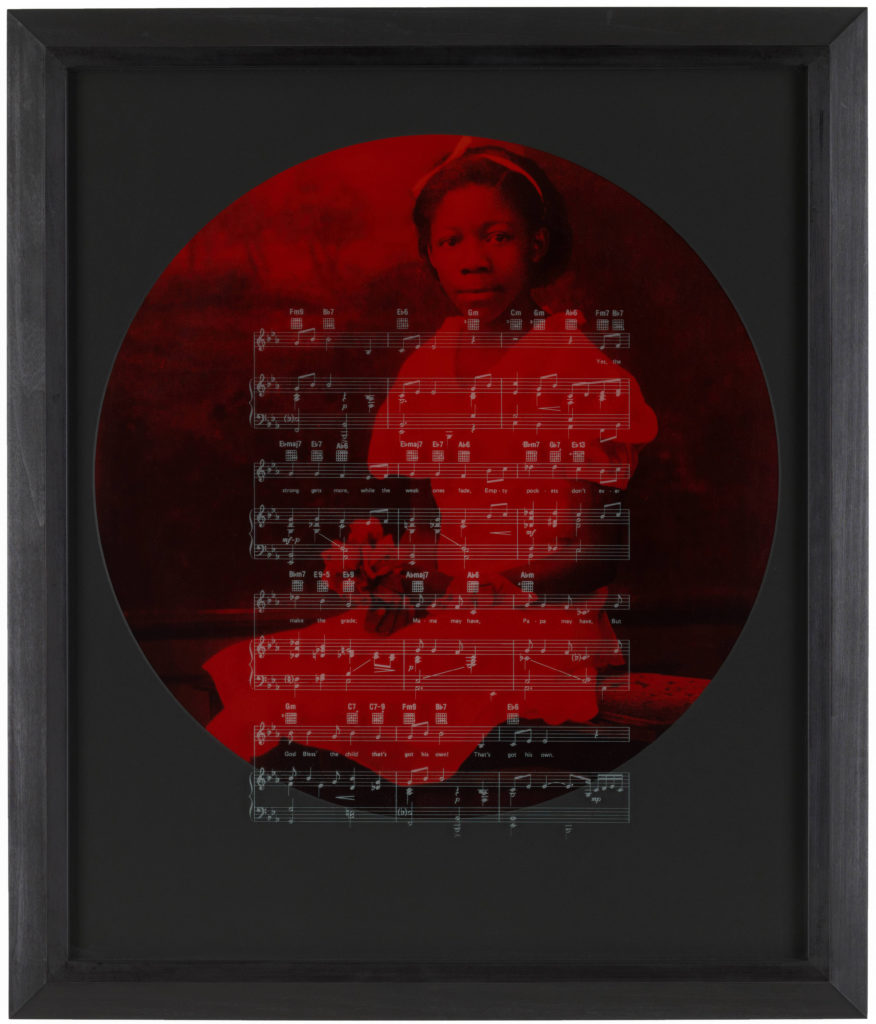

In From Here I Saw What Happened, the images Weems draws from are cropped, tinted red, like the bloodshed that is not immediately present, placed in circular mattes that emulate the lens of the camera, and covered by glass sandblasted with Weems’s famously poetic prose; that circular lens, like a spotlight or crosshair, focuses on the subjects, but exposes the intent of the shooter. As well as the oppositional gaze of the subjects. Even in physical captivity, their eyes express dignity and dissent. The subjects captured by Zealy are mostly positioned naked and profiled, much like mug shots or anthropological specimens, revealing a race so eager to demean another in support of theories of superiority that it renders those responsible pathetic, and yet more, deeply ill.

Science has a long, dark history that includes the mistreatment of darker-skinned individuals: from J. Marion Sims’s establishment of modern gynecology on enslaved women, whom he made addicted to morphine to perform nonconsensual procedures, to the Tuskegee syphilis study. In Harriet A. Washington’s Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present (2007), the author is in conversation with Weems’s work when she draws a direct line between the images captured by Zealy and today’s Black infant mortality rates and a life expectancy that is six years less than that of white people. Weems and Washington are in unison with a chorus that sings the song of reckoning. In 1996, Harvard threatened to sue Weems for her use of Zealy’s images, as she had originally agreed not to appropriate them without permission, but then changed her mind. Instead, as Weems later recounted to Willis, she summoned the university, saying, “I think that your suing me would be a really good thing. You should, and we should have this conversation in court.” The question of ownership shows itself again. Who is entitled to images of enslaved humans who were captured by Europeans? Harvard backed down and simply acquired Weems’s collection. Capitalism is but a white sheet.

Entering the gallery at MoMA where From Here I Saw What Happened is displayed is a bit like entering a time portal. Inside the dreamy grey room in the David Geffen Wing, the viewer is made to feel completely immersed in the throes of a history we often try to escape. Bookended by blue-tinted images of a royal Mangbetu woman named Nobosodrou, positioned to bear witness to her lineage—much like Janus, the ancient Roman god of beginnings and passages. Weems’s commitment to history and memory has reached into popular culture, as Nobosodrou’s style has been reimagined in films like Beyoncé’s Black Is King (2020) and Lemonade’s “Sorry” music video (2016), as well as Angela Bassett’s character, Ramonda, in Black Panther (2018). With narrow context, these films have been viewed as a form of cultural appropriation, just as scholars and critics accused Weems’s series of being sarcastic and nothing more than a revictimization of the subjects.

But to dispose of and forget the reality of this cruel history is another form of violence, of erasure. As the Nigerian proverb states, “Don’t let the lion tell the giraffe’s story.” Is Weems not entitled to a history that lives inside her bones? A history that beckons her? She was called to the South in her Sea Islands Series (1991–92) and The Louisiana Project (2003), in which she explored the landscapes and land built and tilled with Black hands in South Carolina, Georgia, and New Orleans. One can imagine the tremors that exist inside her as she works to bridge the gaps between the memories of the land and waters that betrayed the enslaved in their journeys across the Atlantic, yet also provided a means of escape and sustainability, proving that water is a body too.

All works from the series From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried, 1995–96. Courtesy the Museum of Modern Art, New York

Weems, who studied dance and folklore, is able to identify the silences present in the appropriated photographs and read the gestures of the bodies like a poem. The musical notes of Billie Holiday’s “God Bless the Child” (1941) lay over the frame of a young girl holding sadness in her eyes, perhaps her only inheritance. Each of Weems’s rhythmic syllables lands with impact, taking us deeper into a past that we have been taught to avoid. Weems dissects the messages communicated through their limp limbs, forced smiles, and slouched welted backs. And we see that, sometimes, a camera is a gun.

Carrie Mae Weems’s From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried is on view at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, through spring 2021.