Chloe Dewe Mathews’s Sweeping Chronicle of the River Thames

Chloe Dewe Mathews, Mass Baptism, 23/08/2013, 3.30 pm, Southend-on-Sea, approx. 180, biannually, 51°31’54.6”N 0°43’32.7”E, overcast

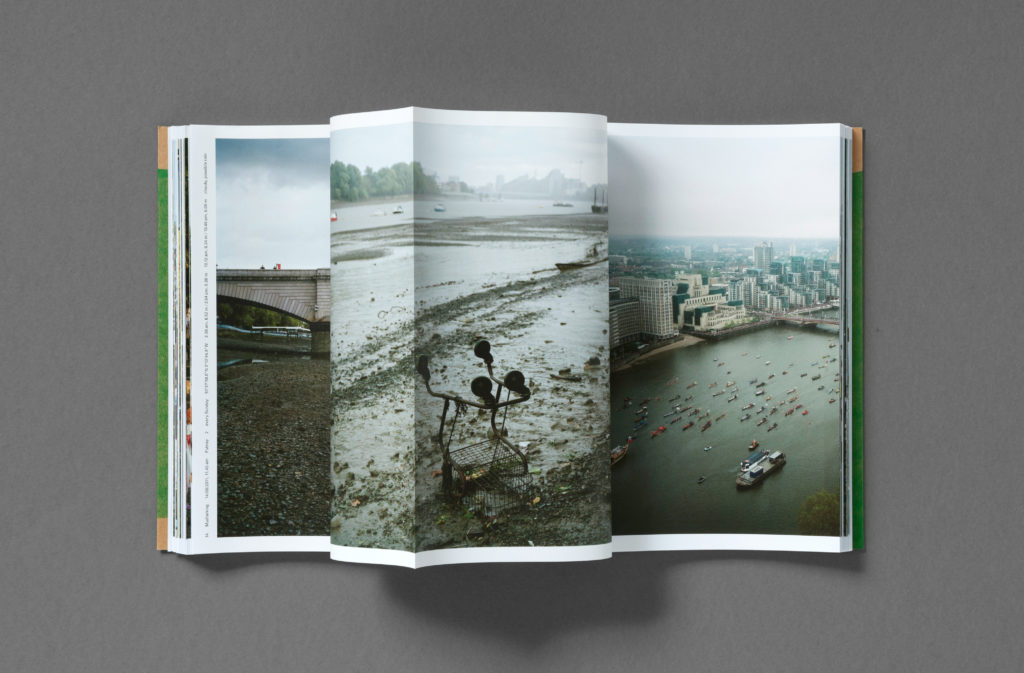

Thames Log is a book that tries both to depict a river and also to encapsulate it, to become it, through stream, drift: a course that feels deliberately uncontrolled, sweeping. Published by Loose Joints earlier this year, the book’s layout is pacey, and there is a refusal to hero key images with pauses or white space. Images fall from one page to the next like tide over a ridge; they lap at each other.

British photographer Chloe Dewe Mathews spent five years—from August 2011 to July 2016—making pictures of the Thames, a river that runs for 215 miles across Southern England. The images were made while Dewe Mathews was simultaneously working on Caspian: The Elements (Aperture, 2018), a project shot along the shores of the Caspian Sea, and in broad terms, the two series do the same things—they show the interactions between people and water, the way human activity can activate or mold a landscape, and how, in turn, a great body of water can shape the communities that live or work around it. The fact that each project feels distinct, and specific, says a lot about the way water can cultivate local differences, shaping cultural practices, honing eccentricities, and influencing everything from the way we mourn, celebrate, and gather, to how we exercise, style ourselves, or decorate.

Thames Log is a very different project than Dewe Mathews’s earlier, celebrated series Shot at Dawn (Ivorypress, 2014), commemorating British soldiers who were killed by firing squads during the First World War. That was about quiet, memory, reflection. Thames Log is more chaotic, more eclectic, and yet somehow, also peaceful—a duality that reflects water, and the many roles it can play in our lives, from the active to the meditative, the sociable to the reflective.

Photographers have returned again and again to water: the lapping surf on a sandy beach, the perfect blue of a swimming pool, the expanse of sea. Some go for the clean lines, the visual order, others for the magnificence of wild nature. Some go for the light, the sparkling dance of glimmers on the surface. Many go for the characters, the sense of a scene set. Dewe Mathews goes for all of it, seeking to capture the plurality of water, the way it can be anything and everything to anyone. This book is not about a personal love of water (though Dewe Mathews does love it) but instead, about the many ways to love it, and the many figures who display that love. It is about how passion, or commitment, or reverence can make something as wild, as uncompromising, as a great river, briefly, one’s personal ally, one’s own.

Lou Stoppard: You worked on Thames Log for five years. When did it become the project that we see here in the book? Did you set out with specific goals in mind?

Chloe Dewe Mathews: The project came out of doing the Caspian work in Central Asia, Russia, and Iran, where I was taking photographs relating to natural resources, water being one of them. And I was always coming back to Britain, to the Thames, and looking at the landscape, as I’d been doing in Central Asia. I began thinking about trying to make work where I’m from—I grew up just by Hammersmith Bridge in London—along this water body that’s so close to me. I thought I’d just start wandering up and down, exploring and seeing if there might be a project in there. It was always in relation to the Caspian work, which evolved to be about human relationships to landscape and natural resources, but also about how ritual plays a part in that, a kind of repeated activity—sometimes religious, sometimes secular, sometimes in great groups, sometimes very personal and private. It was looking for similar kinds of stories around the Thames. I suppose it became the work as you see it now in the process of thinking about how it would become a book.

For the first years, I was just shooting, not thinking too much about exactly what form the results would take. And although I finished making this series in 2016, I was then working on two other book projects, so it took a couple of years—actually quite a long period of time—until I was able to give my attention to it. A river lends itself to the book as a medium, to that kind of linear form, that constant flow and directionality. I always knew it was a really rich subject for bookmaking. But it was only once I got to the stage of making a book that I knew I wanted to make something quite experimental, in which the form would follow the content.

Stoppard: Thames Log feels like a celebration of the photobook, but it also pushes against clichés of format, or our typical ideas of a photobook, by embracing the idea of flow, of something fast-moving and continuous. Is that what you mean when you say “experimental”?

Dewe Mathews: I often find that when I work on projects, I get very used to my own image-making and used to my own mark. And sometimes, you want to disrupt that a bit. And so in this, there’s the situation of using multiple images, at times, in very quick succession. I suppose that disrupts the idea of a single image, or a kind of decisive moment, a fixed moment.

Stoppard: Which, again, really nods toward this idea of a river, of layers of water moving across each other, of tide, drift.

Dewe Mathews: Yes. I wanted to give that feeling of movement and change happening within space and time as well. That’s partly why I chose to have these sequences of pictures. There are also lots of spreads where the image is flowing over the page. That was actually something that Lewis Chaplin and Sarah Piegay Espenon of Loose Joints suggested. I think they were quite cautious to suggest that to me at first, because they were aware that some photographers can be very precious with their images—and for good reason! But for me, partly because it was a good four years after I’d finished shooting when I started making the book, I felt a real need to disrupt this series of work and do something interesting with it, to reinvigorate the work for me too. So that idea of allowing photographs to flow over the pages, which then creates these really nice pictures within pictures when you get double-page spreads, and new juxtapositions, felt really lovely.

I think having a bit of distance from the shooting allowed me to step back and say the most important thing here for me is to create a book that works as a whole, rather than being too precious about each image. For me, it was always about saying, There’s this wealth of material I’ve collected over five years, what do I want to do with that now? Rather than saying, There’s this specific picture and I desperately want to show it in this way. In a gallery context, there’s more of a traditional way of showing the photographs, printed fairly big, put on the wall, and you can see the whole picture. But I wanted to treat the work quite differently in book form. And I think that’s something that, as the years have gone on, I’ve become more and more interested in—that idea of treating each iteration or each endpoint of my work, whether it’s a book, a show, online thing, differently, rather than trying to do the same thing and squashing it into the different forms. Not every project has to be a book, but when it is a book, it should really make use of the format.

Stoppard: In Marina Warner’s essay at the start of the book, there is a quote by Roni Horn about the Thames: “Beneath one water there is always another water.” You can apply that to images as well, this idea that beneath, or behind, every image, there were so many other images that were made, or could have been made—multiple other shots, or setups, or chances that feed into the eventual image.

Dewe Mathews: When I think about how I came to the river, it was on different events, different moments, different weekends, different days. You go to the river and just by chance, you have encountered something or someone. You might have arrived just before something happens. You might have arrived just after—sometimes, it’s just a happy coincidence that you’d seen something. Sometimes, you only see the traces of an event: in the book there’s a photograph of a flour arrow, which is where a running group had been through, and they have left this flour marker on the ground to show which direction to go. Or with a scattering of ashes, flowers that are cast into the water afterwards. I like that idea of, as you say, these events happening in time, but we encounter them at different moments within that timescale. So, rather than always going for the perfect moment, the sort of cover shot of an event, it was about actually trying to echo the human experience of how you encounter these things when you’re wandering along the river.

Stoppard: In the book, there is a thanks to Martin Parr for his support, so naturally, it made me think of his wife, Susie Parr, who’s a big swimmer and wrote the book The Story of Swimming: A Social History of Bathing in Britain (2011). There’s quote in there: “The four entwining themes that characterize early British swimming are might, method, medicine, and magic.” Those themes apply also to some of the themes that come through in your book. There is this element of looking at spiritual practices, rituals. There’s a sport element. There are elements of the healing ideas that we associate with water. You have everything from teenage girls drinking, through to these very significant, steeped-in-history rituals that take place, such as the cross floating down the Thames.

Dewe Mathews: I was interested in how everyone comes to the same river and sees something different. They project meaning onto it. This whole idea of a river as surrogate; that, as in the Roni Horn quote, you can look at the Thames and you can see the Ganges, you can see the Congo, you can use it as a conduit to travel mentally to other places. That’s why you also get a lot of really interesting, very diverse activity on the water. I spoke to some Hindu elders in a temple in South London who said, “Oh, the Thames now represents the Ganges to us. All rivers flow into one another, and so they are physically connected.” To them, it is as worthwhile to honor your dead, and your gods, at the banks of the Thames, as going all the way back to the Ganges. I love how totally open-ended the river can be. And how that is reflected in the humans and human activity along it.

There’s a lovely quote from Marina’s essay, where she talks about the river as a commons, and this idea that rules that apply on concrete and earth don’t apply to the river, and so, more alternative activity can take place there. That is the kind of activity I was looking for, rather than the things that we’re more aware of—the regattas, genteel rowing clubs, and so on. I saw the river representing something other and something natural, and therefore, undefined; all sorts of things are possible there that aren’t possible elsewhere in the city. When I first started researching, I came across a photograph from 1883—an amazing old picture in black and white, of this pastor dressed in black and a woman dressed in white, being baptized in the Thames at Cricklade. And then there are all these spectators lining the banks, who are dressed in black as well. I remember seeing this moment of activation of the British landscape, this extraordinary spectacle, and just thinking that that doesn’t really happen anymore. And then, of course, the more I worked on the project, the more I found that it did happen; there were lots of echoes of that kind of activity. If you think of land artists or performance artists, people activating the landscape in a certain way—I’m really interested in seeing laypeople or just normal people doing the same.

Stoppard: There is a real spread of different groups, or activities, depicted in the book. Talk to me about the research process of that, and also gaining access to some of these groups or communities—gaining their trust.

Dewe Mathews: With some projects I’ve done, like Shot at Dawn, the research was incredibly fact-based in terms of talking to different historians, curators, battlefield guides—lots of archives and books. Whereas with Thames Log, much of the research took place along the river—in-the-field research—maybe you’d hear something from one person, or you see something which then makes you think, and then you’d come back to a computer and follow up, calling so-and-so. It was quite a patchwork. For example, the baptism in Southend of a Pentecostal group, that probably took at least a year to actually photograph. I remember someone mentioning, “Oh yeah, there’s a big baptism that happens here just outside Adventure Island,” which is one of these amusement parks in Southend. I remember thinking, Seriously, can that really happen here? I asked, “When does it happen?” They said, “Oh, I don’t know, on the weekends in summer.” And so, I was going there every second weekend and just hanging around, as I couldn’t find out more information—no one knew who the people were who were doing the baptism. And some weekends, I’d turn up and someone would say, “Oh, you just missed them, they came last weekend!” So it took a long time. And then finally, it was almost like an apparition, suddenly seeing all of these people dressed in white robes, who had all come in buses from East London with a Pentecostal Evangelical church, pouring onto the beach, totally transforming the landscape of this very busy British beach.

Stoppard: You say this project is about humans’ relationship to the landscape. Do you see it as being a statement on environmentalism?

Dewe Mathews: Yeah, I think it is. It’s so hard to negotiate or to work out how best to explore those subjects without being preachy and without being know-all, when I don’t know all. But I think that to honor or record people’s engagement with landscape is an important thing. I also think there is that responsibility, or a personal interest, an agenda maybe, to recalibrate the mainstream portrayal of who occupies the river and how. There is such a long, almost burdensome history of the Thames—there’s just so much, so many layers, of what’s come before, that sometimes it’s hard to understand what it actually is, or to see what it looks like today. People have so many associations with the past. So for me, it was also about trying to say this is what contemporary Britain looks like, in the context of our landscape.

Stoppard: You also question the way a lot of people associate the Thames with London—partly, I think, just due to pop culture.

Dewe Mathews: Yes. In the book, London pops up halfway through, but it’s certainly not the dominant place. And I think the more you experience the Thames, the more you realize there’s just so much more to it—you get these bucolic natural extravaganzas in the upper reaches of the Thames. It’s achingly beautiful in certain parts of the river. Totally unspoiled, unoccupied. And then, you get into these strange, scrappy semi-industrial bits. And then, of course, the proper wastelands, part-derelict industrial estates, and bleak, seemingly endless car parks. London is this tiny bit of the story—it plays a tiny but crucial part in a much, much wider context. I’ve lived in London most of my life, and I did residencies both in Oxford and in Southend—two important places in the book—which was helpful to understand how the river was viewed, and lived, there.

Stoppard: it’s really interesting what you say about the weighty symbolism around the Thames, and trying to battle with it as an emblem of so many things, while also introducing new ideas. There was another quote from Susie Parr’s book, that I thought of when looking at Thames Log, where she talks of access to water, particularly for recreation, as being “a class-based conflict.” And I think themes around class really do come through in your book, sometimes subtly, sometimes overtly. For example, when you see the rowing club in Oxford burning a rowing boat as part of a tradition—this idea of burning something of such value.

Dewe Mathews: I was very keen to represent a wide range of social classes that use the river. And as I said, back to that quote from Marina about rivers as commons—it’s a democratic space. One which isn’t private. That was an important part of the work. And as you said, to try and do these things in a subtle way, which allows for people to look and develop thoughts themselves, rather than me pushing an agenda. That’s also a question for me constantly, this weigh up or balance between documentary photography being quite instructive or specific (saying this is what happens here), but then also trying to allow for a degree of ambiguity, or poetry, or open-endedness. I wanted to convey a quiet potency, something other, or on another level, which I think is part of what people come to the water for. There’s this incredible beauty and lusciousness in the surface of the water that can take you elsewhere. And I offset that with the very factual, data-style information about the tide and weather that sits as text next to the images. It was about trying to involve some of those less tangible qualities of water, alongside very specific marked activities on certain days, for certain reasons, with certain groups of people.

Stoppard: It has always fascinated me the way that water has attracted artists, image-makers, writers. There is this quality that is impossible to pin down. And yet, people continue to try.

Dewe Mathews: Well I suppose, as we were saying, it’s something that is open-ended. You see yourself in it, you see other people in it. It becomes a material that people riff off. It’s characterful because it’s flowing, it’s reflective, or it’s cold; it’s got certain characteristics. And yet, it’s evasive and has none. It trickles through everything and has no body and no form.

All images courtesy the artist and Loose Joints

Stoppard: There’s something about water being a thing that is so shared, and so public, yet so highly personal as well, that is intriguing. The idea that something so prominent can also have these very individual, quite secretive things going on around it that you would never encounter elsewhere, even though the water and the river is a part of your daily experience, or a dominant part of your city. I think there’s something in those mysteries.

Dewe Mathews: Yes, there is a publicness in doing anything on the river, and yet the possibility for, as you say, a very private, personal, intimate kind of relationship. And yet, you’re always on view. There is the sense of being taken elsewhere, you’re able to engage in a certain way that makes you forget about that which is happening around you. I think that was also the difficulty of making the work: the knowledge of so many other artists, writers, poets, musicians, every type of artist who has responded to the Thames as a subject, let alone the broader theme of river or water. The Thames has been considered, or photographed, so many times, and yet it still sucks you back in, and there’s still more to be told, and different ways of interpreting it, and questioning it, and documenting it now. I think that’s also why I wanted to make quite a specific kind of artist book, rather than a more catalogue-y type of book. Because there have been so many other photographers and people making work about the Thames over the years, that it had to be something quite specific.

Stoppard: It’s a fascinating project, because it reads as both an attempt to depict the Thames and people’s interactions with it, but also, there is a sense of you trying to encapsulate the Thames in the form of the book—the flow. And even things like the typography, where you used Doves Type, the letter blocks of which were thrown into the Thames in 1917, after a falling-out between the founders of the Doves Press. Today, mudlarkers are always looking for those letters. So to have that font in the book—there was an element that felt like that you could mudlark through the pages. As if the book became the river itself.

Dewe Mathews: That’s a really lovely way of putting it. And I think that’s exactly right. When you’re shooting the work, it’s one thing. And then when you try and translate the pictures into an object, it becomes more about how you can reflect the material itself. A really exciting, stimulating part of the project was that end point of saying, How is it going to become a book? and trying things and going down so many different avenues. The one we went with, as you said, to make the book design take on qualities of the Thames—for it to almost imitate or simulate the river.

Chloe Dewe Mathews’s Thames Log was published by Loose Joints and Martin Parr Foundation in January 2021. An exhibition of Thames Log will be presented by the Martin Parr Foundation, Bristol, UK, in summer 2021.