A Photographer’s Personal Account of the Protests in Richmond

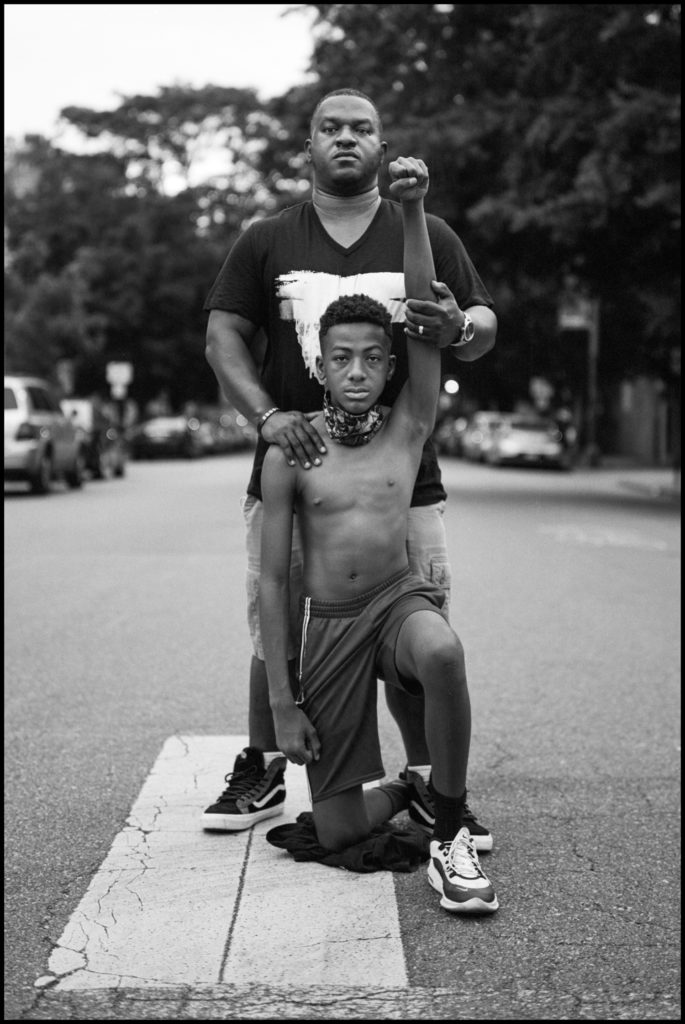

Christopher “Puma” Smith, A protest against police brutality at the foot of the defaced Robert E. Lee Confederate monument, Richmond, Virginia, August 2020

Before the COVID-19 lockdown, Christopher “Puma” Smith made landscape and portrait photographs while traveling or touring as a vocalist with the band Thievery Corporation. Newly grounded at home in Richmond, Virginia, Smith began to use photography in a different way, engaging with the people and ideas of the former capital of the Confederacy. Under Monument Avenue’s statue of Robert E. Lee, Smith documents the forging of new alliances, which he describes in a recent conversation.

Chris Boot: How did you end up documenting what’s going on in Richmond?

Christopher “Puma” Smith: I moved to Richmond in 2017 from Washington, DC. It was to get away from the noise and have a little bit more peace of mind and space, as opposed to the congestion of DC.

Ever since coming to Richmond, my work changed from documentary and street photography to environmental portraits and landscapes. After the death of Marcus-David Peters in 2018, and especially after the death of George Floyd, I was picking up the camera again to physically be present, as opposed to receiving information and updates from biased news sources and social media. So it was to really motivate myself to be present and to converse and talk with certain individuals who are out there protesting and making demands from our local government.

Boot: What exactly is going on in Richmond? It’s a place that clearly reflects the issues that America as a whole is facing, but perhaps in a more intense way right now.

Smith: Richmond was formerly known—and to many is still known—as the capital of the Confederacy. We have a very large number of Confederate monuments here, or we did, and of course, the story of African slaves coming over to this country started here, in Virginia.

In 2018, a tension started bubbling to the surface after the killing of Marcus-David Peters. He was a twenty-four-year-old biology teacher that was shot and killed by a Richmond police officer. During, I believe, his first mental episode, leaving his part-time job at a hotel, he stripped his clothing off, ended up in his car, hitting three cars with no major accidents—but he steered off the interstate and got out of his car; he rolled around in the street for a moment after being slightly struck by another passing car. He started approaching the officer with threats. Tasers didn’t stop him. And he ended up being shot and killed by the police officer—an African American police officer at that—and died at midnight.

His family and community organizers started pressuring the local government for transparency and police reform, partially in the form of a “Marcus Alert” that would send members of a mental-health awareness response team for mental-health crisis cases. This was demanded by the community in House Bill 5043 and approved by the Virginia House of Delegates, but currently needs to be approved by the state senate and signed by the governor; that makes us hopeful. The community also was fighting to end qualified immunity with House Bill 5013, but it was voted out. It was a huge letdown knowing that there were Democrats that sided with Republicans to kill the bill.

Boot: You say “community organizers.” Was that principally Black Lives Matter? Or were many other groups involved?

Smith: With Marcus-David Peters’s case, it was mainly the family. His sister Princess Blanding, is leading that movement, but other independent local organizers have heavily supported it from day one. We don’t have a local chapter of Black Lives Matter. In 757, which is Hampton and Newport News, there is a chapter up there, and it’s called Black Lives Matter 757. They have been in town recently and over the years that I’ve been in Richmond.

Boot: What are the other forces at play? From your pictures, it looks like many different groups, like gun-lobby groups.

Smith: There’s a lot that’s happening besides asking for police reform. There is a huge eviction crisis in Virginia. Richmond is the second city, I believe, in the country with the highest eviction rates. The residents who are at the forefront of these evictions are African Americans, unfortunately. Richmond is predominantly African American. There are organizers who have been fighting for those facing housing issues though. I know of Omari Al-Quadaffi, who works with low-income housing communities and has been on the frontline for these families and individuals. We also have groups like Friends of East End Cemetery and the Evergreen Restoration Foundation, who are working hard to revive two forgotten, heavily overgrown African American cemeteries: East End and Evergreen, where Civil Rights activists like Maggie L. Walker and John Mitchell Jr. are buried. Even veterans from as early as WWI are buried there and were allowed to be completely forgotten, their graves damaged and vandalized.

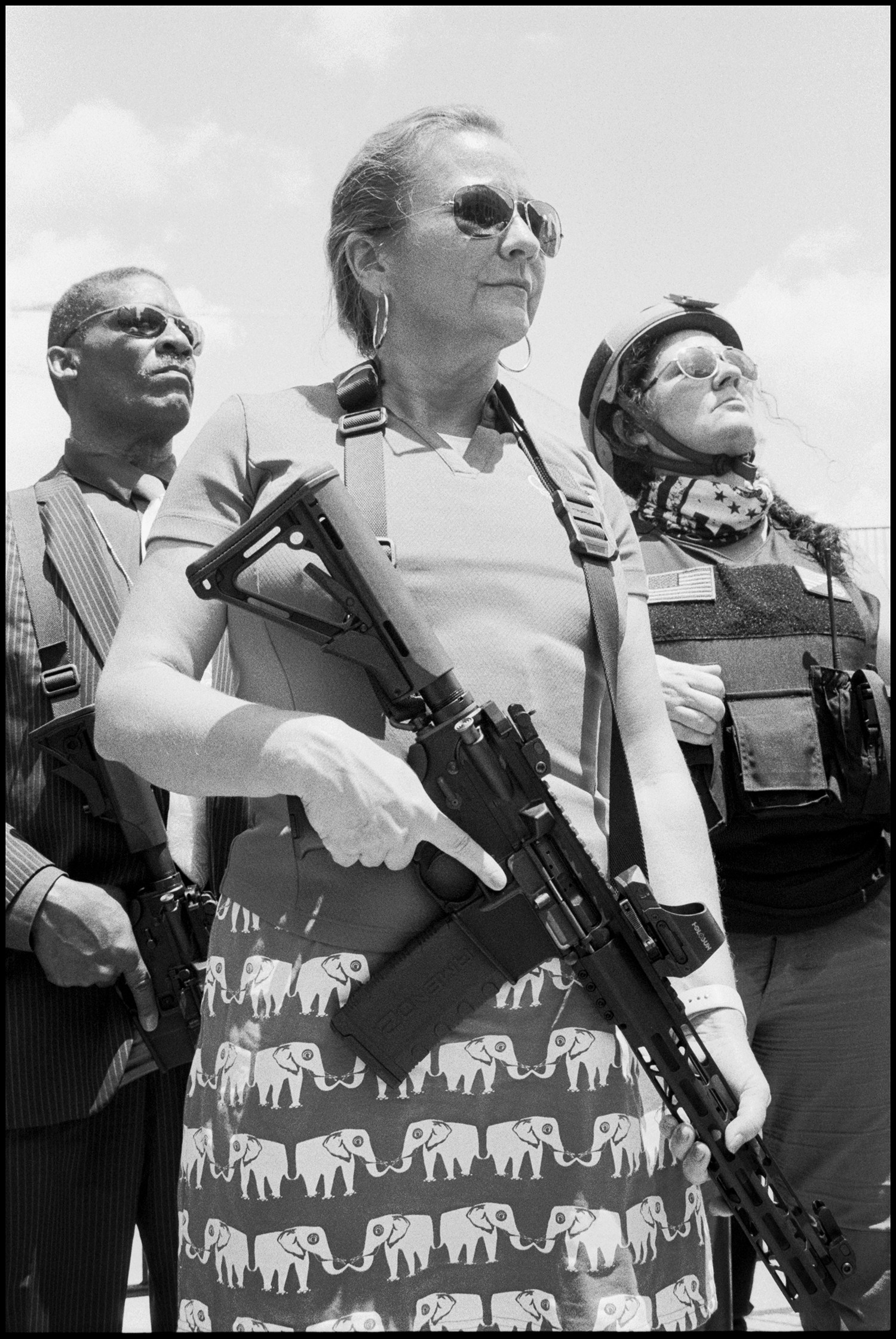

Also, on July 1 of this year, Richmond passed a lot of new laws, and a big chunk of that had to do with gun restrictions. There was a huge uproar leading up to this, and in January the largest demonstration happened and around 22,000 pro-gun activists and militia groups came through from all over the country into the city to protest around the State Capitol building.

So, it’s kind of melding into this antigovernment movement right now. What has also caught my attention are the African American gun-owners, and your white pro-gun communities—they are both demanding that they still have enough authority to be armed and to protect their own communities. Now, there’s a lot of disagreements around that and between these communities, but what has been obvious to me is that this is what these two communities, or all of the pro-gun communities so far, have in common. They also want police reform. All sides agree to demilitarize the police department. They want more transparency. And they don’t want these Second Amendment–reform laws, because they want to be able to protect their families and communities—both sides do not believe that the police can efficiently police their communities. They don’t trust the police department, basically, in my opinion.

Boot: One gets the sense that it is a place where white supremacists still get to voice their views.

Smith: Yes. What has also bubbled back up to the surface is the talk of the Confederate monuments. I talked to Regina Boone. She is the daughter of the creator of a local newspaper, Richmond Free Press, which mainly reports on the African American community here in Richmond. She expressed to me once that her father has fought for the removal of those statues since the ’60s. The sites of those monuments have melded into the scenery here. But now, as people are pushing for police reform, the degree of anger around that conversation and racism has risen, so that in Richmond, they are on a roll of eliminating any kind of racially divisive symbolism, such as schools named after Confederate soldiers and any Confederate symbolism. A law passed on July 1 was used by Mayor Levar Stoney, a young Black man, to bypass a city council vote to immediately start removing Confederate monuments. There is still a community here that wants to protect this so-called “heritage,” but it’s a predominantly Black city—all the public schools here are predominantly Black, and we have a mayor who is Black, there’s the lieutenant governor who is Black, and our city council consist of members that are Black, white, and people of color. So it’s very strange that they still had these monuments erected down Monument Avenue and around the city today.

You have to remind yourself to follow the dollar though. The statues that are on Monument Avenue provide tourism dollars, and tax incentives for the avenue residents and of course, their property value goes up. The main and largest statue is of Robert E. Lee. He led the Confederate Army and has one of the most infamous reputations in the history of the Confederacy. The property that his statue sits on was donated by a local family, and the city accepted it in 1890. They were the main individuals suing the government based on the deed their family signed in 1887 with the city. Others were suing hoping that the judge, who lives in the area, would side with them so their property value and tax incentives would remain. That judge has since recused himself. The current lawsuit that prevented removal is going to trial in October.

Lee’s is the only state-owned statue, and it was thought by most that state code prevented removing it, but it is becoming clear that wasn’t true. The area has now become this rallying point for the community, for the city. I mean, the statue is covered in graffiti and spray paint, and it’s become this central art piece. Most of the events that are happening, most of the rallies and protests, end up or start at this monument. There have been orchestras out there and local artists. There is a community garden, basketball hoops, and even wellness and voter-registration tents, but those tents were violently removed from the area by police. Even the Floyd family came down and had a hologram art installation and spoke to the community there. So it’s been mainly this powerful space for people to just come together and converse and share their opinions on what’s going on now. The circle has been renamed Marcus-David Peters Circle by locals.

What’s bizarre is that Robert E. Lee was against monuments to the Civil War. He knew it would be divisive, then and now.

Boot: With so many arms and such strength of feeling, it looks like a war coming. Do you feel this is a sort of continuation of the Civil War?

Smith: Well, there has been a group called the Boogaloo Boys that has come into a lot of people’s attention. Learning about the Boogaloo Boys, we know of 125 groups spread across the country. There’s no local leader. They are known as far right. They are antigovernment, and they believe in inciting a civil war. They, at least the people I have talked to, believe that this government, this dual-party system, is not for the people at the end of the day.

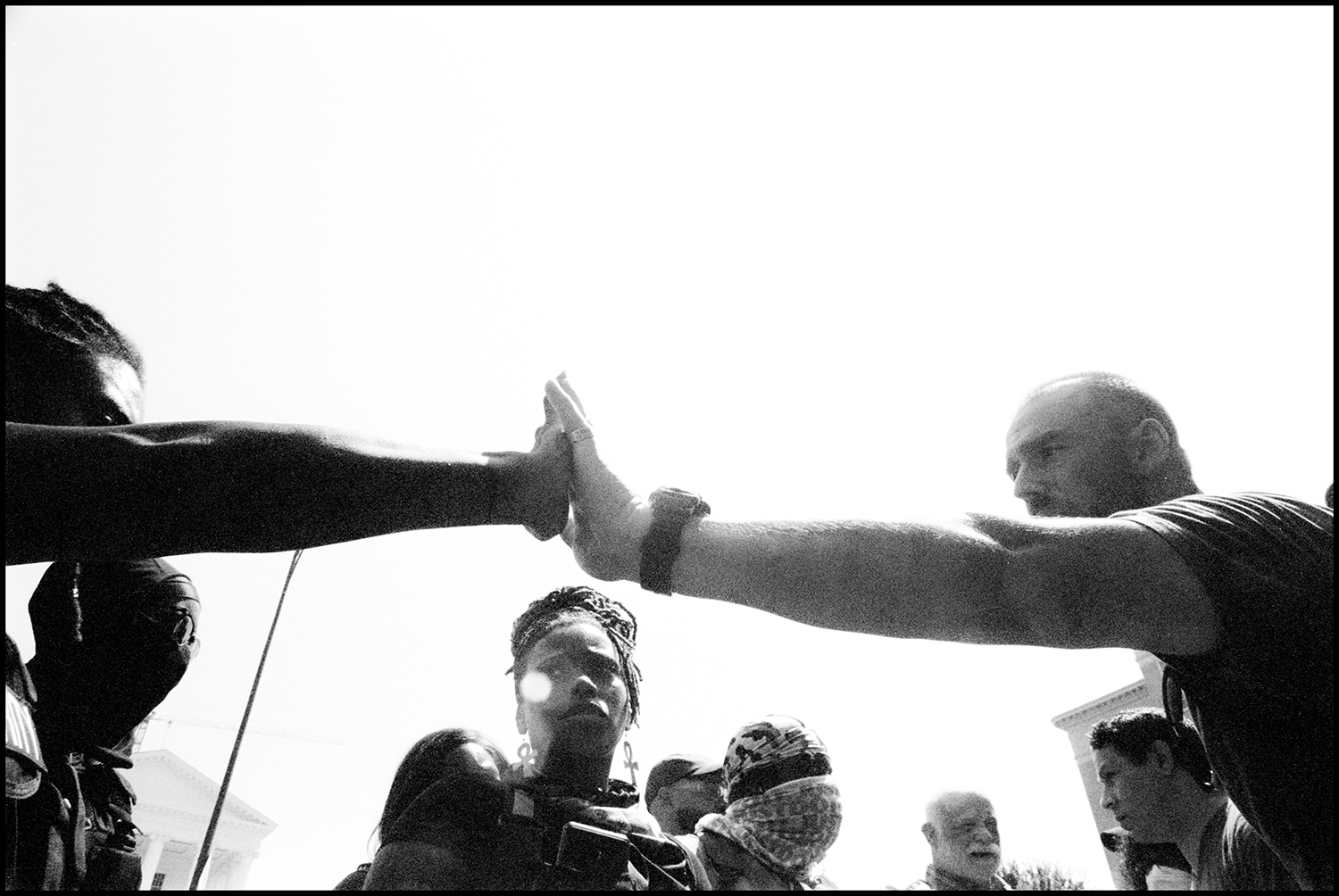

But this group, which is seen as white supremacist, they have been collaborating with the Black Lives Matter 757 chapter. Just the other day, they were invited to a Black Guns Matter rally organized by BLM757. They have shown up for funding schools and for anti-eviction rallies and other protests around the city—though not received and welcomed whole-heartedly, but they have been there. I think their purpose, which they have admitted to, is for some degree of civil war and anarchy to just bring down the system, however that looks.

For me, man, it’s always tricky. There’s definitely a racism problem. There’s also definitely this superiority issue that we have in this country that I think stems from capitalism. But sometimes I don’t know if people are fighting for status, or they are fighting to eliminate or expose racism within the hierarchy here in this country. Because now, there is so much degrees of division, quarreling on social media, and building of brands off of the mistakes from one’s own community members, unfortunately, within African American groups fighting for police reform and equality. Time always tells what people are really fighting for.

Boot: Are you saying that the extreme right-wing groups are seeking to forge an alliance with Black groups to take on the government together?

Smith: They haven’t explicitly come out and said that. But they have stated their intent—the Boogaloo Boys. This specific group and this specific sect here in Virginia, they have said they are for civil war, and they are antigovernment, and they are for police reform; they want to demilitarize the police department. They want to be able to protect their own community in the way they want, in the way that they see fit. But they have been walking and marching side by side with Black gun activists. On the day Black Lives Matter 757 did a Black gun rally, there was Black Lives Matter 757, there was the Huey P. Newton Gun Club, the Original Black Panthers of Virginia, there were some white militia groups that showed up, and Spike Cohen, the VP nominee for the Libertarian Party was invited to speak and get enough signatures to be on the ballot. It was just this melting pot, but the common ground was the Second Amendment and distrust of the police.

Boot: You see that in your pictures. For the most part, your images don’t show conflict. They show motivated people, activists—maybe they’re angry, but I don’t see venom. I actually see a relatively civil process going on that you could say is a good example of people resolving their issues peacefully.

Smith: Yes. I think I’m more productive when the protests and the rallies are stationary. Marching down the street is good to capture photographically for historical purposes. But the rallies that are stationary, when they start and when they end, is my opportunity to go and record speakers and to interview people one-on-one on their opinions and their perspectives. It hasn’t been as chaotic as Portland. Some of the protests have gotten out of hand. Some cars got set on fire. Buildings are being damaged, protestors being violently handled by police, arrested, and even charged with felonies, unfortunately. But more has been done just pressing our local politicians and policy-makers, and organizing around that, using the internet and our dollars, instead of going out and just bashing windows and setting cars on fire and destroying property. But I cannot deny that the protests and rallies have helped in some way.

I agree with MLK. It’s the voice of the oppressed, and that’s how a certain percentage knows how to get their point across. But at the end of the day, for me, it’s again, follow the dollar and use your dollar to really make a difference. I think people are catching on to that.

Boot: Are you trying to make an account of every side of these arguments? Are you talking to white racists?

Smith: Yeah. I’ve talked to some white militia groups and members of the Boogaloo Boys. The community here is still very suspicious of them, and some of them have just flat out not accepted them and basically told them they’re not welcome. They’re anywhere from nineteen to twenty-two years old. They grew up in rural Virginia. They’ve admitted that they’ve had twisted perspectives from early on and still do now. I think because they’re coming out at such a young age and collaborating with the Black community—I think, for the better, their perspectives are changing. Hopefully. I’ve also talked with Senator Amanda Chase, who is running for governor and is pro-gun and believes in replacing statues. In her words, the Confederate flag for her means iced tea and The Dukes of Hazzard. I’ve also briefly talked with Chuck Smith, who is an African American attorney running for attorney general and a veteran who also is pro–Second Amendment and believes in replacing statues.

My reason for talking to people is to find where the common ground is. Ever since I came to Richmond, I listen to right-wing radio more than left-wing radio. I listen to Jeff Katz and John Reid and Rush Limbaugh and Hannity and Glenn Beck. I listen to all these people, and I listen to left-wing radio also. I’m giving up on mainstream media. I want to see how we can actually get something done, and not just, you know, rage and let it pass. What I found is that people want transparency, and they want to have a voice—an opinion on how their communities should be policed.

Boot: Are you trying to be objective in the traditions of photojournalism? How do you conceive of your own role as a photographer and a gatherer of documentary evidence and stories?

Smith: I am going out to be an individual, to really learn the community, continue to learn Richmond and the community that has been here fighting for years. It’s really about trying to be an individual, and not going out there with any kind of bias. Again, just trying to find common ground.

But, it’s very tricky, because people want to put you in a group. They want to see: who are you with, who are you defending? And yes, I have my own personal opinions. But again, it’s trying to find: what do we all want, and can we get it accomplished? And maybe, in the midst of that, these prejudices and this degree of racism can be eliminated, once everybody finds a common purpose and a force to communicate and converse and be together for this one purpose. I am going out there really for my own personal education, and to meet people one-on-one, and then to get their perspectives, if they’re willing to share.

Boot: Are you hopeful?

Smith: For the community members, yes. I mean, people who are not elected officials and the people who are starting grassroots movements and have been consistent. I have become hopeful again. I have become hopeful as far as meeting a goal, which is police reform. I am hopeful for that.

Boot: Are you hopeful for America?

Smith: [Laughs] As far as what?

Boot: A better path than the one that we’ve been on, which is division. Hate and division.

Smith: No. Honestly, I’ve tried to be as positive as I can in my short time here. But I see a pattern that we are not breaking, and I am not hopeful. I am not hopeful for America. But I don’t know how we start over. I don’t know how we slow down. Capitalism has been ingrained into everyday life and how we function and how we communicate. It’s hard to answer that, man.

Boot: When you say “capitalism” in that context, I presume you mean the way capitalism favors some and discriminates against others.

Smith: There is always going to be a hierarchy. Looking at Richmond, we say we give everybody a fair chance, but we really don’t, because we don’t focus on the basics of humanity when it comes to just living in general and when it comes to surviving in a capitalist economic system. In Richmond, we don’t focus on and invest enough in education, and it’s predominantly Black schools. If we don’t start there, how are we saying, you know, everybody is getting a fair chance—if we don’t start with education first?

Boot: And health second, presumably.

Smith: Yes, it’s very frustrating.

Boot: You have another source of making a living, which is as a singer with a band that tours a lot, so you’ve seen a lot of places. You’ve worked all over the world. You’ve worked in Ethiopia, for example, doing photography assignments. Is it unusual for you to focus on one place and your hometown in this kind of way? Is this the first time you’ve done that, delved into one community as a photographer and a documentarian?

Smith: Yes. I think I’ve finally got the discipline to focus my camera on a story. I’ve shot for papers, taught photography in nonprofits, and I was hired by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine to travel to different rural regions in Ethiopia to document pre- and postnatal care in 2019. I’ve also traveled for ten years with Thievery Corporation, mainly as a vocalist, but always with camera in hand documenting the band. Now, I think my previous experiences have given me this discipline. And especially being a person of color in America has allowed me to have the discipline to not be scatterbrained when I’m picking up the camera. It’s allowed me to actually give myself this kind of tunnel vision, in a sense, to focus and form relationships and converse around this one story. The camera motivates me, picks me up and makes me be present. But it is the research and meeting people which is hard to do in this time of social distancing and, you know, “don’t call me, just text me or e-mail me.” People just don’t want to deal with people one-on-one or face-to-face anymore. So it’s harder even to get people to express their perception honestly on audio and on camera. It’s frustrating and depressing at times, but it’s something that I’ve become more passionate about. One day at a time, one person at a time, one conversation at a time.