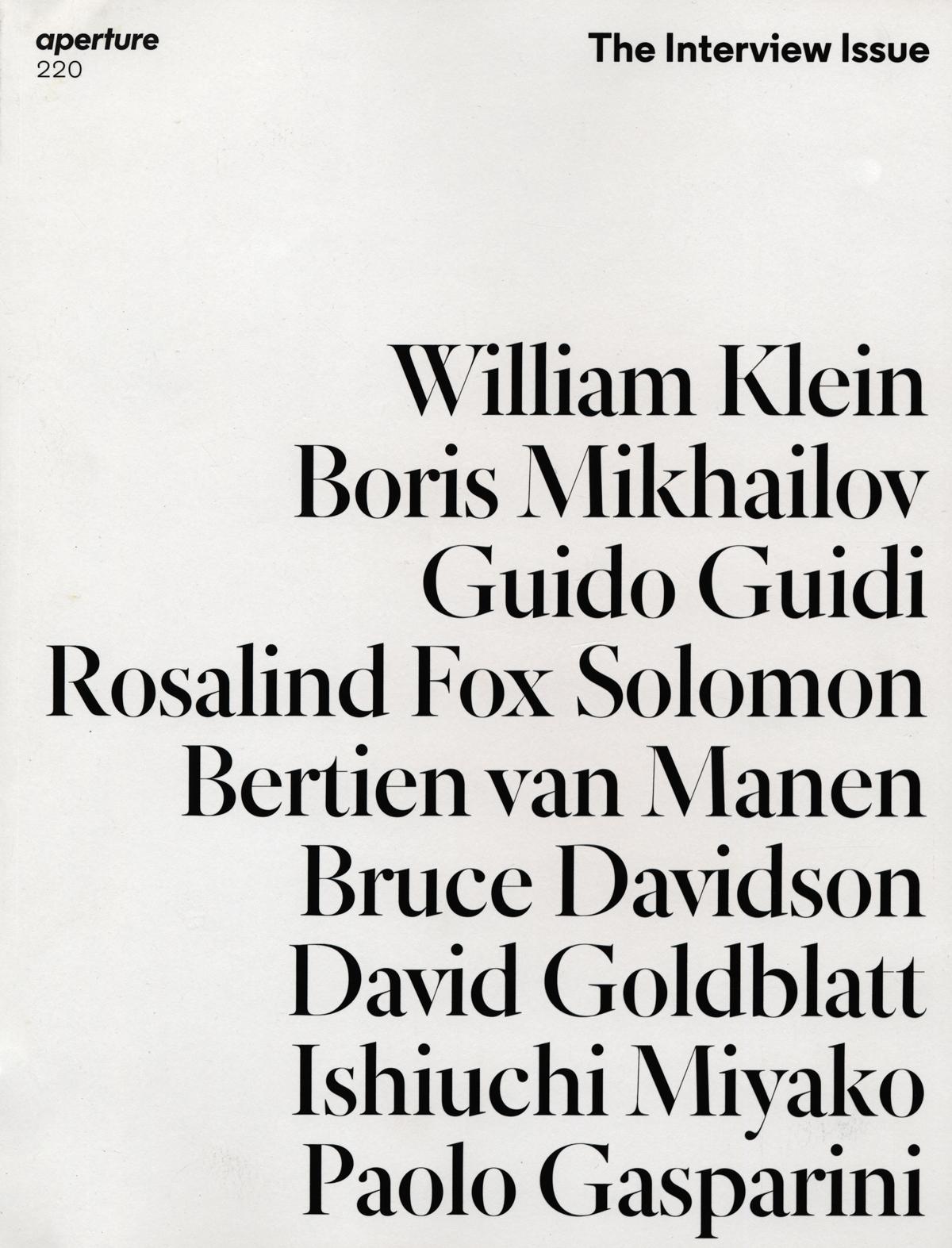

David Goldblatt, Mrs. Miriam Diale in her bedroom, 5357 Orlando East, Soweto, October 1972, from the series Soweto

“Events in themselves are not so much interesting to me as the conditions that led to the events,” David Goldblatt says to interviewer Jonathan Cane. While other photographers have focused on the turmoil of South Africa’s colonial and apartheid years, Goldblatt, who is now eighty-four, tends to train his lens on quieter subjects emblematic of the prevailing social order. He will soon be republishing his series In Boksburg (1979–80), in which he looked at daily life in a white middle-class community in the years of apartheid. Among his many series are Some Afrikaners Photographed (1961–68); On the Mines (1973), documenting South Africa’s mining industry; and The Transported of KwaNdebele (1989), addressing the plight of black workers forced to travel great distances for employment. More recently, for Ex-Offenders (2010–present), he photographs individuals on parole at the scene of their crimes.

The conversation that follows took place last May at Goldblatt’s home in an old Johannesburg suburb; like much of Goldblatt’s work, it was framed by events in the news—the controversy over a statue of Cecil John Rhodes, the mining magnate and imperialist symbol, at the University of Cape Town, for instance. In protest of the university’s faculty, overwhelmingly dominated by white men, an activist threw human feces on the Rhodes statue in March 2015; the statue was subsequently removed, and has since become a symbol for “decolonizing” the university. This concern with monuments has been central to Goldblatt’s work for many years. Also happening around the time of Goldblatt and Cane’s talks were xenophobic conflagrations across South Africa—deeply unsettling violence involving exiles and refugees from other African countries. The photojournalism documenting these recent conflicts throws into relief the incisive work Goldblatt made during the most violent times in South Africa, and which he continues to make still.

Jonathan Cane: You’ve photographed many walls, fences, boundaries. I think of your 1986 photograph Die Heldeakker, The Heroes’ Acre: cemetery for White members of the security forces killed in “The Total Onslaught,” Ventersdorp, Transvaal, or any of the precast fences in your iconic 1982 book In Boksburg.

David Goldblatt: They occur in my work because they are part of our life, absolutely. But I haven’t particularly sought them out. I am very conscious when I drive around the country of the number of game fences we have, and what the effect of those are, and I have photographed those. A lot of farmers have switched to farming with game, because they save on labor and they are able then to fence off their land in such a way that they make it virtually impossible for people to walk over it, and to use their land as a means of getting from point A to point B, never mind doing anything else on the land. So there are these very high fences dotted around the country now, many of them electrified, and it’s not clear to me whether the electrification is to keep the game from moving too close to the fence or to keep people out.

Cane: You live in a gated community, which is typical in South Africa. How do you feel about that?

Goldblatt: I feel very negative about it. We have a boom at the only motorcar entrance in the suburb, and a guard there, and by municipal regulation he’s not allowed to stop anybody, so it’s meaningless, really. And he might question a person coming through but he’s not really supposed to. We have an electrified fence that we put up after my wife and I were held up inside our house by men with pistols. It protects us, but I don’t kid myself. We’re not in Fort Knox. It would be very easy to break in again. I just think that I’m not a very tempting take, you know.

Cane: The vibracrete fence of prefabricated, modular concrete slats and pillars, for me as a Joburger, is emblematic. My father always said we must turn the fence outward—have the good side out and the crappy one facing in. That was our civic duty to our neighbors.

Goldblatt: I’ve never thought about that subtle variation on the use of the vibracrete fence. I think they are very significant as part of our makeup, really. It’s a cheap way of fencing your property, and obviously very popular. If I had to refence our property, I might be tempted to use it, but I would most certainly reject it. And I have photographed some in the course of my work.

Cane: You’re republishing In Boksburg. Why republish this book three decades later?

Goldblatt: Well, there’s a man in Germany by the name of Gerhard Steidl, who is probably the prince or the king of photographic books, who is totally obsessed by quality. And I am in the very fortunate position of having become a sort of favored photographer of Gerhard. He told me at lunch a few years ago, “I want twenty books from you in the next twenty years.” So I’ve got an extensive program to fulfill [laughs]. Of course, it’s not possible to do it; it would be quite impossible to do. But he more or less accepts whatever I suggest we publish.

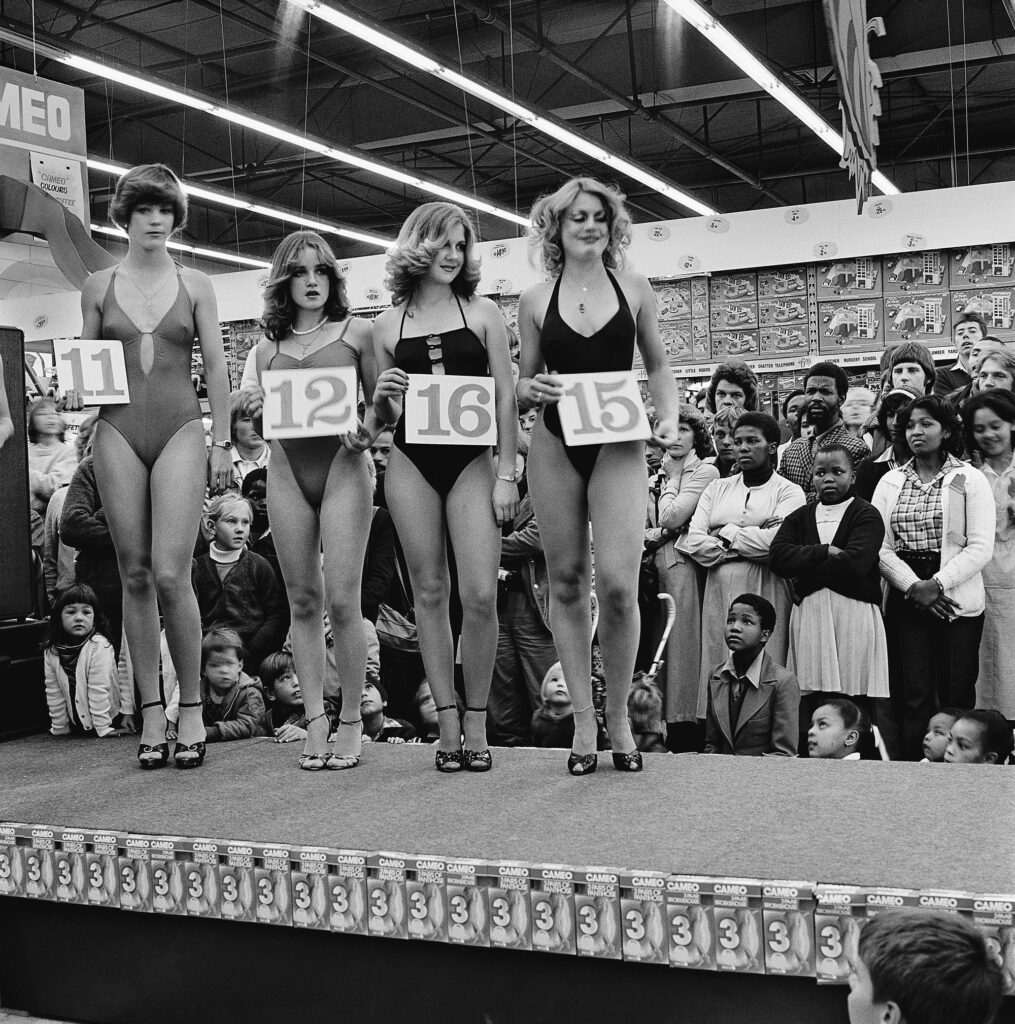

Cane: You wrote in your original introduction to that book that in Boksburg you observed the “wholly uneventful flow of commonplace, orderly life.” This included weddings, garden maintenance, and sports in a whites-only town. Observers have noted that you are interested in the commonplace rather than the dramatic, that your violence is the violence of a vibracrete fence rather than “necklacing” [the apartheidera style of execution where aggressors forced gasoline-filled tires around their victims’ torsos and then set them alight].

Goldblatt: Yes. This is perfectly true. First of all, I am a physical coward. I shun violence. And I wouldn’t know how to handle it if I was a photographer in a violent scene such as James Oatway photographed last week for the Sunday Times [of the so-called xenophobic violence]. I think he is very brave. But then I’ve long since realized—it took me a few years to realize—that events in themselves are not so interesting to me as the conditions that led to the events. These conditions are often quite commonplace, and yet full of what is imminent. Immanent and imminent.

In Boksburg was partly about the banality of ordinary, law-abiding, and also, on the whole, moral people, who were knowingly living in a system that was quite immoral and, indeed, insane. We were all complicit in it. And that complicity is, I suppose, what In Boksburg is about.

Cane: Do you think by republishing it you’re saying something about a kind of continued complicity?

Goldblatt: I wouldn’t. First of all, I claim nothing for my book.

Cane: That seems like a spurious claim to me.

Goldblatt: No, I don’t think it is. I would claim that the work is done with some insight, and that possibly these insights are relevant, and possibly these insights will percolate and, by osmosis, become part of the consciousness. But I’ve never, ever thought that what I do will actually directly influence someone to do or not to do something.

Cane: Is that why you’ve always claimed you’re not an activist?

Goldblatt: Because I am not an activist. An activist takes an active part in propagating their views. My colleagues in photography in the 1980s were activists, undeniably. They acknowledged it. They claimed that this was their role. And I respect them greatly for that.

Cane: Some people disrespected you because they felt you weren’t enough of an activist.

Goldblatt: Yes. That’s par for the course. I have to accept that. But I wasn’t prepared to compromise what I regarded as my particular needs. For a time, I think some of the people who later became very good friends of mine, and who are still my best friends, were rather suspicious . . .

Cane: . . . because the world was burning, and you were taking photographs of people mowing their lawns. Did that seem to you at the time to be a very interesting, strange approach?

Goldblatt: I thought it not only strange, but very uncomfortable. I mean, just now with Alexandra burning and Soweto burning, and parts of KwaZulu-Natal, I have felt what I often felt during those years, that what I was doing was probably irrelevant, but I had to accept that this was the way I am. I am not James Oatway or Paul Weinberg or John Liebenberg, who went right into the depths. I am what I am.

Cane: You talk to the people you photograph, in the sense that you don’t sneak a photograph of them.

Goldblatt: I don’t sneak a photograph of them, but I often don’t talk.

Cane: But do you always ask permission?

Goldblatt: Oh, yes, invariably I ask. But in general, I try not to talk. The reason being that I want the subject to be very aware of the situation, and conscious that he or she is being looked at. I set up the camera, and then I don’t look through the camera, because I want the subject and me to be in eyeball-to-eyeball contact. It’s sometimes quite difficult, because you’re dealing with a powerful person. You are really trying to assert your mastery of the situation. And you have to be in control of the situation. That’s quite tricky. I want the subject to feel tension. I don’t want the subject to feel particularly comfortable with me. I used to do a lot of portraiture of leading people: Mandela. [Joaquim] Chissano. [Robert] Mugabe. [Kenneth] Kaunda. And so on. Not [Samora] Machel. I never photographed Machel. I would insist—often at the cost of serious differences with security, police officers, and the like—on putting the subject into a straight-back chair, something like that, rather than an armchair, or what I call a goma goma chair, which you sink into.

We had an interview with Mandela just before he became president. It was in the house in Houghton where he was living then. Anyway, he’d been up since four o’clock in the morning doing exercises and whatever else he did. He came down at five for that appointment, and I had insisted—because the house was full of goma goma chairs—that I wanted the straight-back kitchen chair. The press officer, Carl Niehaus, who was later in disgrace , said, “You can’t put Mr. Mandela onto a kitchen chair.” I said, “I insist.” I said, “I’ve come to photograph Mr. Mandela, not the furniture: I want a kitchen chair, and I insist.” Eventually, when he saw the photograph, he conceded that it was the right thing to do. You’ve got to take control of the situation. Otherwise, it’s a runaway.

For me there is no question that the land itself, that “land” as opposed to “the landscape,” is something that I would like to explore.

Cane: Language is fundamental to what you do.

Goldblatt: Well, the kind of photography that I am interested in is much closer to writing than to painting. Because making a photograph is rather like writing a paragraph or a short piece, and putting together a whole string of photographs is like producing a piece of writing in many ways. There is the possibility of making coherent statements in an interesting, subtle, complex way.

Cane: You are known for your long captions.

Goldblatt: I usually offer them in a form where they can be split. I learned from Life, Look, and Picture Post, which were expert at conveying information on three, four levels really. There were the photographs, which were the simple focus of what the magazines were doing, and then there were three layers of wordy information. There was the main caption, which was short, pithy, and gave you some basic text. There was a subsidiary caption, usually written in a lighter face or a smaller point size. Then there was a text. By means of these three layers of information, or verbal information, or written information, they conveyed a great deal in a really digestible way.

Cane: You have collaborated with some of the most respected South African writers: Nobel Prize–winner Nadine Gordimer wrote an essay for your first book, On the Mines, from 1973, and recently you published TJ & Double Negative with Ivan Vladislavic. Tell me about your relationship with Ivan.

Goldblatt: I admire him greatly, first of all, his ability to write books. But perhaps more relevant and more important is his ability to seize upon often insignificant details of our life here that are key to an extrapolation of our life. So in one of his books, there’s a man who is the proofreader for the Johannesburg telephone directory. I mean, you’ve got to have an extraordinary imagination to imagine that. In the book that came out of what we did together, he exhibits a similar kind of imagination. Part of the story involved [the collection of misaddressed] “dead” letters of a Portuguese man who used to be a doctor, and one of the highly qualified men in Mozambique, who comes here and can’t get work but becomes a letter sorter.

Ivan has this ability to, I don’t know, to somehow extrapolate our life in terms that are often amusing and yet tragic, and always, always relevant to our life.

Cane: Which writers do you still hope to work with?

Goldblatt: I would say that there are two people with whom I would love to collaborate. Marlene van Niekerk [Afrikaans novelist, poet, and professor]. I can’t imagine what we might collaborate on, but I’d dearly love to. And Njabulo S. Ndebele [author and former vice chancellor of the University of Cape Town].

Marlene and I have had a couple of public discussions. That was when I realized what a formidable person she is, and her grasp of things. She knew my work intimately, and she asked questions that penetrated right to the heart of things and yet without harassing me. Subsequent to that, I asked whether I could meet her. At that time, as an extension of what I had done in Particulars [made in 1975 and published as a series in 2003], I was attempting to do some nudes, and I had done one or two, and then formed the idea that I would like to do portraits of people in the nude. So we made a date to meet outside Cape Town for lunch, at which I told her my undisguised and unlimited admiration for her, and I said to her, “I would like to do a portrait of you in the nude.” She laughed. She said, “Absolutely out of the question.” She said, “First of all, I am in the academic world here and that just would be unacceptable, but secondly, I am a very shy person, and I just wouldn’t do it.”

Cane: Do you have an archive of projects that could not or should not be done?

Goldblatt: Over the years, there have been things that I have wanted to do, but, for one reason or another, couldn’t. Mainly these have been things that were just very difficult to do. For example, in the 1980s I wanted to photograph subjects who had been detained and tortured, and I photographed some of them in the course of providing visual evidence for a court case. A number of photographers did this. Lawyers would want pictures of people who’d been shamboked [whipped] in prison; they’d want pictures showing the wounds. I did a number of those. But I wanted more than that. I wanted to do portraits of people who had been tortured. I did one or two, and it was terribly difficult because people were afraid. There is one picture that has been published quite often of a young man with his arms in plaster. I did two photographs of him, one front and back, and I photographed one of his colleagues. But I gave it up. It was just too difficult to get people who were prepared to accede to this.

Cane: You mentioned that you are digging back into your archive. What does it feel like to look back—and to still have twenty books planned?

Goldblatt: Well, I wish I had twenty books still planned. Every now and again I catch myself and say, “Am I really this old?” I don’t feel very old. But at the same time, I am aware that my body is changing, and my ability to handle complexities. Age has affected me. I think it would be true to say that when I was younger, the sex drive was a very potent force in what I did. That is less the case now, partly because of physical changes in the body. Do you know the work of Borges, the Argentine writer? He said something marvelous once, and I can never quite remember it, but basically he said that in your youth—this referred to a writer—if the stars are right, and everything is in place, then in his or her maturity, his work might contain a subtle, hidden complexity.

Cane: You’ve always insisted on a strict boundary between your “professional” work done for clients—including the powerful South African mining houses—and what you call your “personal” work. After the 2012 Marikana massacre, when thirty-four striking miners were shot dead by the South African police, did you have occasion to reflect on that dividing line in your work?

Goldblatt: Well, I don’t think I fully grasped the depth and extent of the exploitation of migrant men working in this country. That became clear to me during this incident at Marikana. It was clear that the migrant workers were in the position of sellers of their labor, in a very weak position, whereas the mining houses were immensely powerful, and there’s no question that they exploited that difference in power, if you like, over many years. They exploited it. There is currently a class-action suit against the large mining houses for the damage done by silicosis, which is a chronic lung disease caused by the silica dust miners breathe in while working. I photographed some aspects of this. I came along at the end of this long, sorry tale. They had stopped mining asbestos when I came into it. I have to acknowledge that I did things for the mining houses that, in the light of what I now understand better, I should not have done, and should have refused those assignments, those commissions. Or I should have handled them differently.

In my own personal work, in my book On the Mines, I have touched on these things in quite brutal photographs. But I didn’t sufficiently illustrate that much. And we’re not out of that yet. The relationships still stand. Just in the last week or two, there was an announcement of the take-home pay of the executives. It was appalling. Not one of them came up and met the strikers and sat down and talked to them. Not one.

Cane: What has age taught you?

Goldblatt: I will say that I’ve learned to be a good craftsman. That goes without saying. I don’t think you can seriously engage in photography if you’re not a craftsperson. You have to be reasonably competent at handling situations, and the camera obviously. But I have to say that as I’ve entered my ancient years, my craftsmanship has deteriorated. I forget too much. I take too much for granted. I had a very good friend who was a great architectural photographer, Ezra Stoller, an American man, who was so famous for his architectural photography that great architects would want to “Stollerize” their buildings. And he said to me once—and he was then about the age that I am now—he said that he had lost the ability, the critical faculty to make judgments of prints. Ja, I’m sad to confess that I think this is happening to me. I’ve been printing now for the last few months, and I’ve reestablished my connection with my work that I had lost for a time.

Cane: I always wanted to be old. Does that sound silly to you?

Goldblatt: No, no, not at all. I had a brother, Nick, ten years older than me, and I loved the lines in his face. I had a smooth face. I used to envy him to no end. In many ways, I wish I were younger. But I think, on the whole, I accept growing old. What I am very conscious of is that I probably don’t have many years left of active work. I have to be able to climb onto the roof of my camper. I have to be able to drive fourteen hundred kilometers to Cape Town. I must be able to do these things. And my ability to do that is probably limited within the years left. When I was forty, fifty, sixty, and seventy, it seemed like there was an unbroken span in front of me. Now that I am eighty-four, it’s a bit unrealistic to hope that it’s still an unlimited span. Gerhard Steidl’s twenty books in twenty years is somewhat unrealistic maybe.

Cane: Did you know that you are very much in fashion right now? If you visit any fashionable person in South Africa they will have a David Goldblatt in their lounge.

Goldblatt: I didn’t know that. My sales figures don’t bear that out.

Cane: They even have a particular way they’re framed and they’ll be hanging next to, like, a Zander Blom or maybe an early William Kentridge print. How do you feel if I tell you that you are at the height of fashion right now?

Goldblatt: I feel very vulnerable, because that’s bound to change. Fashion is essentially a passing phenomenon, and ja, I am absolutely not at peace with it.

Cane: I want to talk about the South African veld. I was driving across the country the last two days and was struck by how exquisite, how devastating it is in some ways. J.M. Coetzee wrote in White Writing that whites lacked a vocabulary for the light and the color of the place. I think some people would say—you said it yourself, I think, once—that there was a time when you stopped running away from the light of this place, and tried to find, or did find, a language for that here.

Goldblatt: I think that’s true. Just now, in the Karoo, where I went after photographing the student dethroning [of Cecil John Rhodes’s statue at the University of Cape Town], I went up to an area near Langford that I’ve often looked at with the idea of photographing it. I once went there about four years ago, five years maybe, and got permission from the farmer to go over his land. I was in my camper, and I drove in there, and I did a photograph that I’ve never really liked. But I knew that there was something there that I wanted to explore. Just a few weeks ago, I went back there, and for two days, when I had a weekend, I went back to that farm and walked over it, found a koppie [a small hill], drove along the Cape Town–Johannesburg railway and did some photographs, which I think are the beginning perhaps of something. For me there is no question that the land itself, that “land” as opposed to “the landscape,” is something that I would like to explore. I don’t quite know how. But when we speak of “the landscape,” that already is a value judgment. It considers that you have looked at the land, and formed a picture around it that makes it into a scape.

All photographs courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town

Cane: Making a photo of the land without making a landscape.

Goldblatt: A photographer who I really admire, Guy Tillim, has done that in São Paulo, in Tahiti, and he has done it in Johannesburg. The photographs that he did in Johannesburg are amazing. They appear to be fuck all. I think they are great. It’s something that, ja, I’ve been conscious of for a long time.

How do you resist this need to find order? And yet, how do you do that so the photographs are not just chaotic?

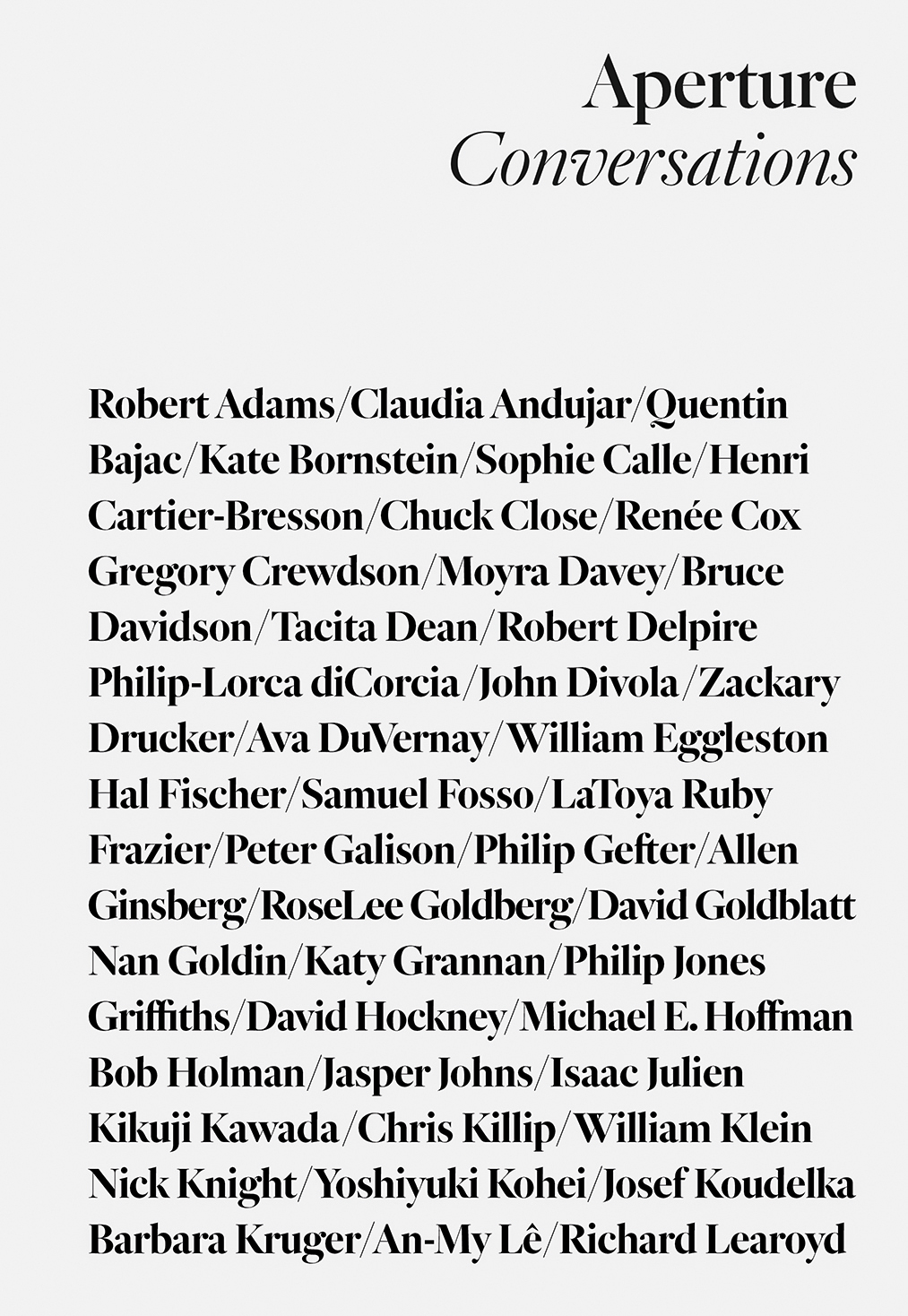

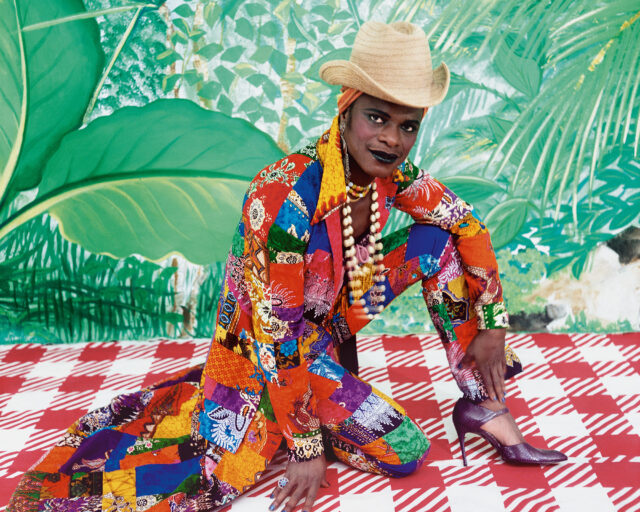

This interview was originally published in Aperture, issue 220, “The Interview Issue” and republished in Aperture Conversations: 1985 to the Present.