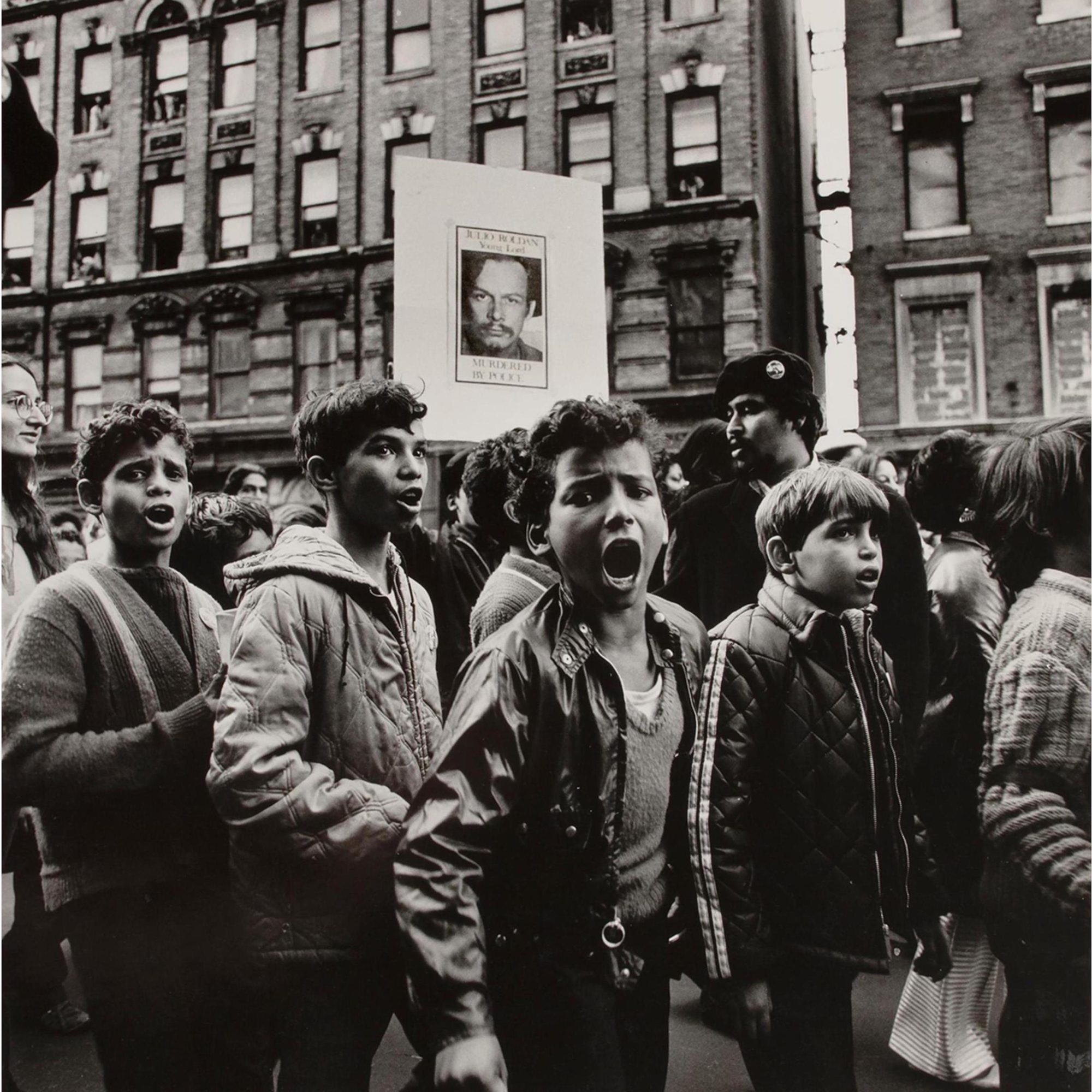

Hiram Maristany, Children in the funeral march of Julio Roldán, 1970

Courtesy the artist

My first encounter at the latest edition of Greater New York—the survey of artists living and working in New York City that MoMA PS1 has put on every five years since 2000—was with Diane Burns’s “Alphabet City Serenade.” In a video on loop, the artist, whose parents were Chemehuevi and Anishinabe, recites her poem about Indigenous alienation and downtown displacement, connecting Manifest Destiny to the gentrification of the late-’80s Lower Manhattan she wanders: “I’m American royalty / walking around with a hole in my knee / I’m a hopeful Aborigine / trying to find a place to be / oh East Village, ay yay yay yay yay yay yay.”

Courtesy Bob Holman

This time, Greater New York features forty-seven artists and collectives, the “greater” extending to include the Haudenosaunee, the confederacy of Indigenous nations (Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca) referred to as Iroquois by colonizers, and artists’ ethnicities are listed in wall texts to emphasize the global scope of what “New York” art might mean today. PS1 curator Ruba Katrib, along with director of the museum Kate Fowle, MoMA curator Inés Katzenstein, and independent curator Serubiri Moses, introduce the show by invoking science-fiction writer Samuel R. Delany on a gentrifying Times Square at the end of the twentieth century.

Manhattan-born Delany argued that integral to a city’s “vibrant life” is “contact,” which the wall text paraphrases as the “encounters, liaisons, bonds, and casual exchanges made possible in spaces that bridge social worlds and cut through hierarchies established by commercial interests.” The lamented loss of these sorts of spontaneous, often anonymous meetings during the COVID-19 pandemic has become a familiar refrain, especially in New York, where such “contact” is meaningful, magical, and a part of the mythos. At the same time, the expansion of mutual-aid networks and the uprisings in support of Black life have reemphasized the importance of community-based care and communal refusal of racial capitalism. With the pandemic of 2020 continuing into 2021 and now 2022, many may wonder what’s next. Seventy-nine-year-old Delany recently told an interviewer, “One of the things that I know as a science-fiction writer is if there’s one thing you cannot predict, it’s the future.”

Courtesy MoMA PS1

Both documentary and surrealism are prevalent in the show—not, the wall text explains, in opposition but “integrated and entangled as they represent and reimagine the world.” And yet, I left Greater New York with a strange sensation, perhaps as tiresomely simple as the fact that, because this show (like so many others) was delayed by the pandemic, it felt uncannily out of time. That most of the documentary photographs on view recall the past—the violence, protests, and joys of previous eras—made the last two pivotal years in New York feel like a fever dream, haunting but only half-remembered. As I moved through the gallery, I could still hear Burns’s flat singsong—part nursery rhyme, part dirge—and I left with her melody stuck in my head.

The loss of spontaneous, often anonymous meetings during the COVID-19 pandemic has become a familiar refrain, especially in New York, where such “contact” is meaningful, magical, and a part of the mythos.

Gentrification, migration, and belonging are taken up by works made both thirty years ago and this past year alike. Iranian artist Hadi Fallahpisheh’s Young and Clueless (2021) explores immigration—dislocation and cat-and-mouse competition—with cartoonish drawings of the aforesaid plus dog, created in the darkroom with a flashlight on photosensitive paper. Seneca artist G. Peter Jemison takes on the Canandaigua Treaty of 1794 acknowledging Haudenosaunee sovereignty, which—despite violations and subsequent treaties—to this day stipulates annual supply by the US Army to the tribes of yardage cloth, which Jemison incorporates into a map-like work, along with old family photographs, sketched roads, and scraps of language.

Courtesy MoMA PS1

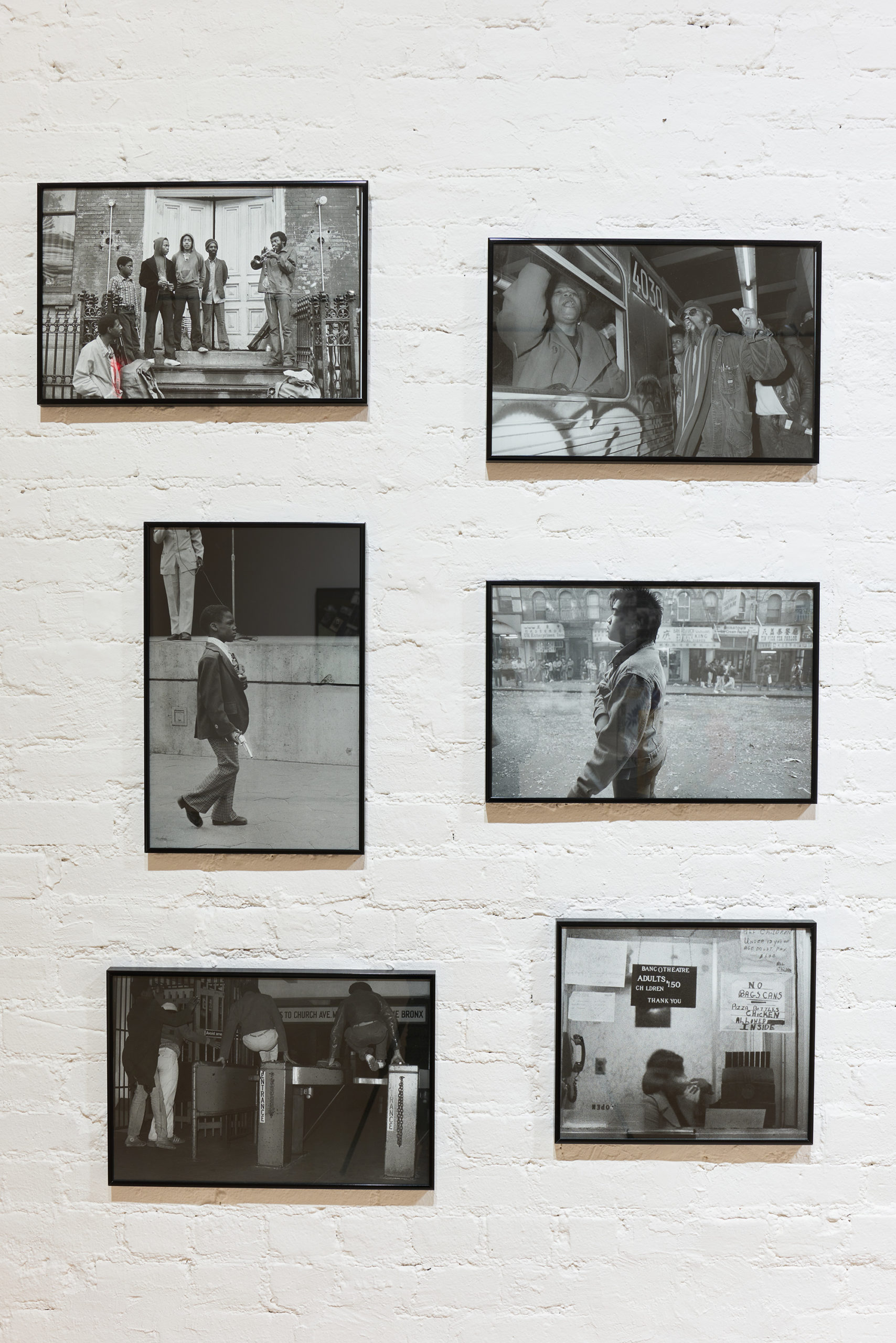

Striking documentary photography from the 1960s–80s makes this period loom large. The images of Puerto Rican American artist Hiram Maristany fill one wall, where freedom and play exist amid violence and confinement in East Harlem of the 1960s–70s. Maristany was the official photographer of the Young Lords; and these stylish images, rightly recognized today, likely faced a different reception by institutions at the time the Young Lords sought civil rights and self-determination in the decades pictured.

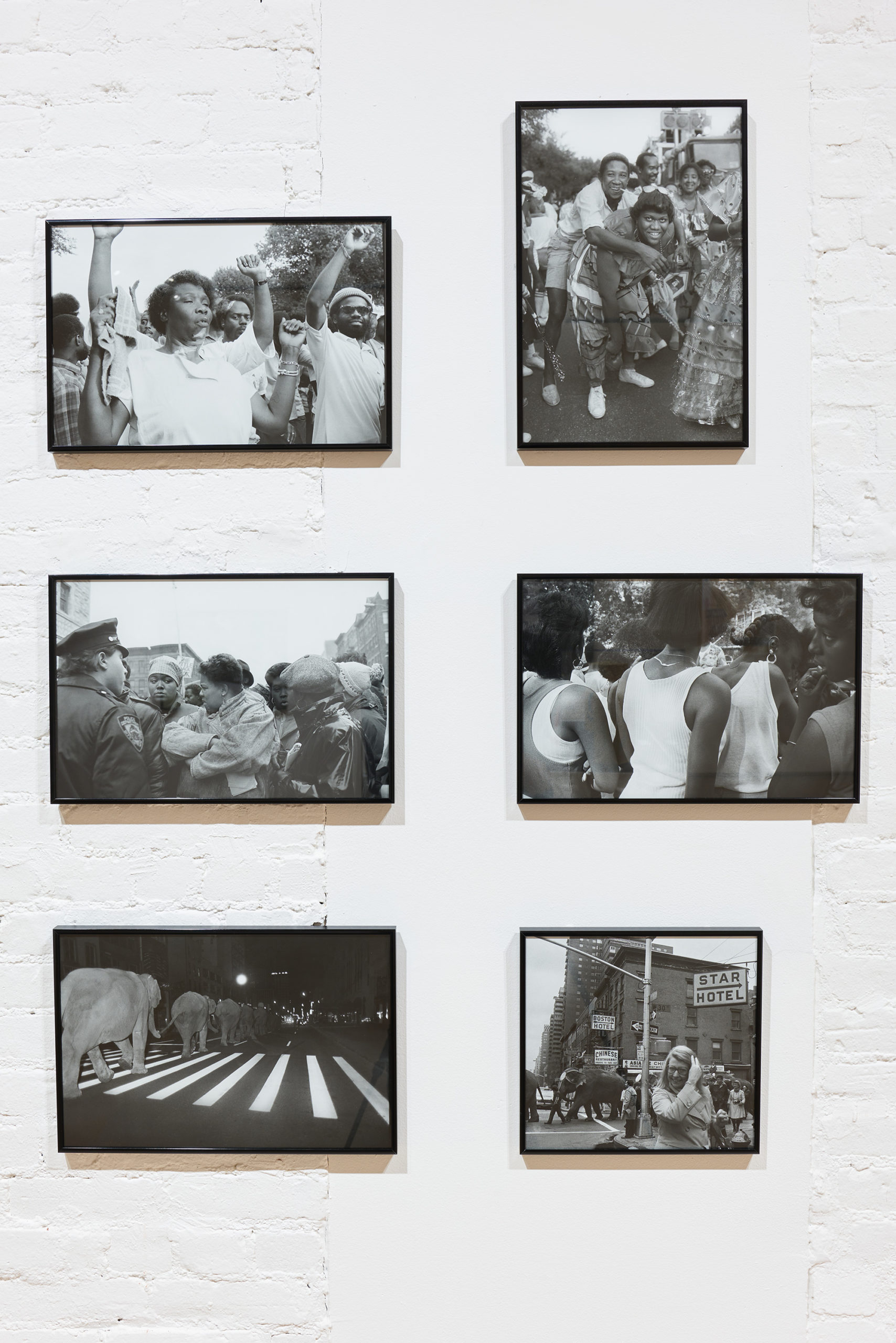

On another wall, Marilyn Nance’s carefully chosen moments—like those of revelers on Brooklyn’s Eastern Parkway at the 1986 West Indian Day Parade, or people jumping the subway turnstiles in 1975—create a potent portrait of the era. Girls Listening to Rap Music (1986), their poised attention beautifully captured from behind, hangs beside the front-facing young women of Police and Demonstrators, MLK Day March. Little Black Book. Carol Taylor (1/18/1998), cross-armed and staunch. One might imagine these women are the same girls a decade later, and wonder where they are today.

Courtesy the artist

Perhaps, I began to feel, the photo-based works of Greater New York tell a more complicated story about the tenor of time.

The Swedish artist Marie Karlberg’s film The Good Terrorist (2021) is based on Doris Lessing’s 1985 novel of the same name, about a squat of Communists who debate housekeeping, the Irish Republican Army, and their own plot to blow up a fancy London hotel to further the group’s political cause. The film, made during the pandemic in an empty Upper East Side apartment, follows comrades played by artists like Nicole Eisenman and Jacolby Satterwhite—whose own work is displayed downstairs in the exhibition (Never) As I Was: Studio Museum Artists in Residence 2020–21—as they disagree about how best to oppose capitalism and fascism with bourgeois finger-pointing and leftist racism and sexism (“You don’t seem to understand the value of property,” Karlberg’s character’s boyfriend tells her. “You haven’t even read Marx’s The Law of Value”). A transcendent dance sequence to “Ave Maria” deftly signifies the violent climax.

Greater New York has been criticized for its “pitch-perfect politics” rather than more boldly “seeking disapproval.” I bristled at these responses. (Instead of work addressing Indigenous land sovereignty that one critic deemed safely politically correct, would they have preferred an art that more radically embodies the kind of Land Back activism that has recently implicated institutions like MoMA itself? Seems unlikely.) But I also couldn’t help but wonder if the critiques came from the same root as my strange sensation—perhaps stemming from some similar source, if leading to different conclusions.

Courtesy the artist and Office Baroque, Antwerp

Visiting a second time, I felt that what has been mistaken for nostalgia by critics is, in fact, the employment of time—the true subject of the show’s photographic works—as a looking glass. What I additionally craved, fairly or not, was a more palpable sense of how the last two years have changed the reflection. The curators were interested, they’ve said, in conveying the city’s international and intergenerational art world, and in complicating the linearity of time and exchange of influence between artists of different generations. The works of both young and long-gone artists never recognized in their lifetimes hang side by side.

As do the years in Robin Graubard’s series Peripheral Vision, with documentary images taken between 1979 and 2021 displayed on mostly unframed paper, punks, mafia thugs, Times Square pregentrification, and more, together in a scrapbook patchwork. Bettina Grossman’s Phenomenology Project (1979–80) is a collection of dreamlike cityscapes seen through the warped reflections of storefront windows. It’s an easy but nevertheless effective gag, the funhouse grotesquerie of wavering American flags not at all up for the task. A room over, in the surrealist tableaux of Indian artist Avijit Halder, friends drape, throw, and wrap themselves in a brighter fabric: with Halder’s late mother’s saris they express fluidity—of gender, but also of time and place as colored by movement and memory, and by grief.

Two images by British Nigerian artist Rotimi Fani-Kayode—whose work explores Black queer desire, transgression, mortality, and alienation—feel both of the past and for the present. Half Opened Eyes Twins, made in 1989, the year Fani-Kayode’s life was cut short by AIDS-related complications, shows the mirrored pair sitting, nude and illuminated in darkness, each covering one eye, the other open to meet the viewer with a question unique, I imagine, to all who come upon this indelible photograph.

Courtesy MoMA PS1

More abstractly, Vietnamese American artist Diane Severin Nguyen’s ephemeral sculptures made from found materials are like exquisite biological specimens, captured at close range before they decompose. She specifies that the gallery wall opposite be slit open for light to stream through—a reminder of the natural world, the machinery of the camera, and the artificiality of the museum itself. Nearby, Japanese artist Yuji Agematsu conveys the experience of quarantine in New York with a collection of detritus found on the street during his daily walks. Displayed in cellophane cigarette-wrapper assemblages on plexiglass shelves, they form a grid of 366 captivating curiosities in miniature.

Shelley Niro’s (member of the Six Nations Reserve, Bay of Quinte Mohawk, Turtle Clan) Resting Place of Our Ancestors 1–4 are large-scale photographs of ancient fossils on Lake Erie rock faces. British and Ugandan artist Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa intersperses archival images with his own, along with a simple brick-and-wood sculpture, threatening and mundane. In both these artists’ works, time and provenance are in play to consider the ways in which history remains with us, obscured.

Courtesy MoMA PS1

“Have we been looking, these many years, at the combustible surfaces of our historical present? Have we been paying attention?” Wolukau-Wanambwa asks in Dark Mirrors, his recently published collection of essays on (primarily US-based) fine arts photo and video work. With an eye attentive especially to the photographic book form, his criticism is itself “a sustained examination of what it is that hides in plain sight as its presence is unveiled or intimated by the image,” he writes.

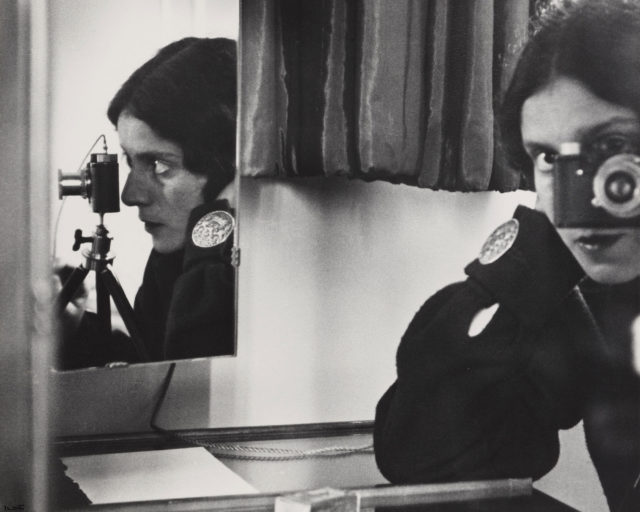

At Greater New York, Wolukau-Wanambwa’s Separation(s) (2021) is a triptych of the same anonymous man wearing glasses and a suit and tie: the subject is white, with white hair, maybe seventy-something. Foggy plexiglass hovers a few inches over the prints, where the figure is traced lightly in ink, giving the multiply exposed man a ghostly stutter. What historically might have been the image of a trustee or CEO hanging unquestioned on the walls of some hallowed hall or corporation here becomes a monument to seeing itself—foregrounding the lens through which we understand the past, the sketchy mirror by which we strain to see the uncertain future.

Greater New York 2021 is on view at MoMA PS1, Long Island City, through April 18, 2022.