Editor’s Note: Bruno Ceschel

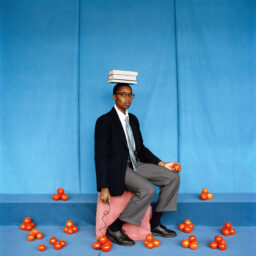

Jane Mount, Ideal Bookshelf #706 Bruno Ceschel / idealbookshelf.com

I was sitting in my doctor’s waiting room with my mom like I did every Wednesday when I was ten years old—I had developed an allergy to house dust and was getting weekly injections as treatment. From among the publications piled up in the waiting room that afternoon, I picked up one about maritime activities. I remember it like it was yesterday: suddenly, flipping through the book’s pages, I noticed a feature about a yacht sailing in a tropical sea with a crew of teenage boys. In some of the photographs the boys were naked, and in one photo in particular, you could see part of one of the boys’ pubescent genitals. It was probably the first time I had seen the cock of an older guy. That photo caused a hormonal earthquake inside of me that forced me to secretly rip those pages from their place and take them with me. I kept them for a very long time, hidden in my room.

That day, now nearly thirty years ago, I consciously encountered the power of desire and photography for the first time. Those carefully hidden pages offered me a portal to an otherworldly place of ecstasy, a place I didn’t know existed until then: a paradise that those photos made “real.” Those pages have long since disappeared, but for years they were my loyal companions, my promise to happiness. Those photographs were my only escape from a small conservative village in the Italian countryside.

Paradise often lies between the covers of (photo)books. The binary desire to have or to be is the key to revealing such a paradise to our own eyes. Desire is like those glasses needed to see a 3-D movie: without them, the film just looks dark and out of focus.

This issue of The PhotoBook Review endeavors to explore the nuanced relationship between pleasure, photography, and the photobook—a very powerful triangulation which has always been the foundation of my own interest in photography. (It is no accident that the organization I founded, Self Publish, Be Happy, uses happy and naughty as programmatic names.) As Lesley A. Martin mentions in her publisher’s note, I am indebted to Charlotte Cotton, a previous guest editor, and to her assessment that a meaningful creative culture has to take into account each actor’s personal experience.

The issue is organized as one would a big party. The contributors are a mix of friends and my ideal party guests, most of whom were invited to bring along a photobook that has been a tool of lust and arousal, or otherwise a giver of pleasure—from the platonic to the lascivious. The result, in the form of the feature “PhotoBook Lust” (including special web exclusives), is a cacophony of beautifully confusing, heartfelt personal testimonies mapping the idea of desire, in its many forms and inclinations. Such a knot of desires untangles to reveal a touching testament to our times.

Of course, it would be difficult not to look at the desire around the book as an object itself, and who better than photographer Todd Hido to talk about his own extensive collection of photobooks and what prompts him to possess them. On the opposite end of the spectrum, we find editor Simon Bainbridge rallying for artists and publishers to create new digital forms for photobooks. He points toward a promised land that is, to many such as myself, hard to imagine. Such a promise is darkened by the question of whether the misfortune of digital editions so far can be attributed to their lack of tactile pleasure (and uncollectibility).

To further explore the relationship between the tangible and intangible, I asked artist Lorenzo Vitturi to produce a three-dimensional manifestation of his own idea of pleasure and photobooks for the publication centerfold. His photograph, titled Candyfloss Ballad (2014), is a naughty take on hide-and-seek, pleasure, and eroticism.

This issue of The PhotoBook Review is sublimely unresolved, confusing, and queering. The chaos of this photobook orgy is exciting and pleasurable. I feel it’s a slightly frantic but successful gathering, and I’m really grateful to all who decided so generously and carefreely to take part. (A special thank you to Joanna Cresswell, who assisted me in the development of the project.) If this issue cannot be conclusive in mapping the complex relationship between pleasure and the photobook, I hope that it prompts you, the reader, to reconsider your own relationship with books, freed from the idiosyncratic diktats of the collector market, art-world hype, and prevailing academic discourses.

Jacques Lacan wrote, “That the subject should come to recognize and to name his/her desire, that is the efficacious action of analysis. But it is not a question of recognizing something which would be entirely given, ready to be coopted. In naming it, the subject creates, brings forth, a new presence in the world.” In my conversation with David Senior, he praises the bravery and tenaciousness of the artist/publisher. I heartily urge such artists to think about the photobook as a catalyst for a new presence in the world—as a new way of thinking and living. After all, this could be paradise.

—

BRUNO CESCHEL is a writer, curator, and lecturer at the University of the Arts London. He is the founder of Self Publish, Be Happy (SPBH), an organization that supports and promotes the work of emerging photographers. SPBH has organized events at a number of institutions around the world, including at the Photographers’ Gallery, Institute of Contemporary Arts, and Serpentine Galleries, London; C/O Berlin; Aperture Foundation, New York; and Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen, among others. Ceschel is also the director of SPBH Editions, which has most recently published books by Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, Cristina De Middel, Mariah Robertson, and Lorenzo Vitturi. Ceschel writes regularly for a number of publications, including Foam, British Journal of Photography, and Aperture, and has also guest-edited issues of Photography & Culture and OjodePez.