Editor's Note: Darius Himes

Jane Mount, Ideal Bookshelf #634 Darius Himes, idealbookshelf.com

Whenever there is a cultural statement involving the “death” of something, you can be assured that a proliferation and rebirth of that very thing is already happening in the nooks and crannies of popular culture. The renaissance is usually spearheaded by artists, and while it doesn’t have the same mass-market reach, it is usually far more culturally satisfying. Vinyl is still around, television didn’t kill radio, college kids now want to become organic farmers, many stores within a few blocks of my flat sell working typewriters, the production process for books has never been more accessible, and you’re reading this on newsprint.

Interestingly enough, newsprint, despite the shuttering of long-standing newspapers around the world, seems to be having its heyday right now. I realized earlier this summer that I had been unwittingly collecting examples of newsprint for the past year: the ANT!FOTO Manifesto (Böhm/Kobayashi, 2013), the state-by-state LBM Dispatch of Alec Soth and Brad Zellar (Little Brown Mushroom, 2012–13), the newspaper supplement to IMA magazine (“Japanese Art Photographers 107,” 2012), Louie Palu’s Mira Mexico, numerous publisher catalogs (JRP-Ringier, Radius Books, MACK), and, obviously, The PhotoBook Review are all printed on a material declared “dead” by popular media.

Change, as the saying goes, is the one constant of this world. I like that sentiment quite a lot. While changes to global society, our national culture, and neighborhood communities continue unabated—think “river of life”— those changes provide rich opportunities for artists to express themselves through ever-evolving mediums. Change represents potential—positive potential, I would argue.

The printed medium is so perfectly universal, I get ridiculously excited thinking about it, and about its future. This has been said over and over, but the conveyance of ideas, both written and visual, through the printed form is here to stay. As Joan Fontcuberta wrote in PBR 003’s Editor’s Note, “As if the irresistible rise of online journals and e-books was to lay waste in two days to print, a technology that has endured for centuries.” Have we forgotten that the right to education, and therefore literacy—the ability to read and gain collected, collective knowledge—arose from the same foment that led to the invention of photography itself? There is no causal relationship, but they are both part of the new level of consciousness that humanity finds itself struggling to adjust to. I’m already sentimental about the future developments in store for humanity in an age where universal education, literacy—including visual literacy—and access to knowledge are not merely considered rights, but have been fully implemented. Did anyone think the application on a global scale of those lofty ideals would take less than a few generations, perhaps a couple hundred years, to implement and adjust?

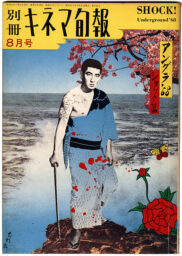

My ideal bookshelf (illustrated above) is a mix of photography, art, and books about ideas. These are books that have sustained me from the moment they entered my life. They have nourished my intellect and my emotions. Open Secrets, published jointly by Fraenkel Gallery and Matthew Marks Gallery, New York, was a book I discovered just after college. Perfectly balancing works on paper, this book interleaved photographs, drawings, and prints in a way that resounded with a sensibility that had yet to be fully developed in me. I felt the same expansiveness when I discovered the exhibition catalog In Quest of the Absolute, published in 1996 by Peter Blum Edition. Here was a book and an exhibition that was published in direct response to—in conversation with the ideas of—an earlier show at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art titled The Spiritual in Art. This notion of a conversation over the decades and centuries between artists and writers is something that excites me deeply—something that the current interest in photobooks past and present so clearly taps into. The essays Mortimer Adler wrote for his masterful two-volume A Syntopicon: An Index to the Great Ideas are a perfect illustration of this point. By surveying the great books of the Western tradition, Adler delineates precisely how particular ideas—Art, Duty, Love, Matter, Time, Will—have been defined over millenia, and how writers and thinkers have responded to each other through their texts. The writer Ananda K. Coomaraswamy—the first curator of what was then called Oriental Arts at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and one of the true great polymaths of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries—complemented Adler’s work decades earlier through his prolific writings on art, philosophy, and traditional, sacred society seen through the lens of the world’s great cultures, including not only early Christian civilization, but the great societies of the East, which gave rise to Indian and Islamic culture.

Books are the perfect vehicle for that conversation. The book is a physical site of learning that, in turn, sparks the imagination, the world of ideas. This applies to both text and imagery. The photograph, and by extension the photobook, allows the reader’s intellect and imagination to come into play nearly equally.

The central task of producing a book is to manifest in physical form an abstract vision in one’s mind. The production process is one of coming up against the realities of manufacturing. All of us in the publishing industry—from artists to editors to designers—have dreams of what our books could be and what they should contain; we then have to come to terms with what is and is not possible or affordable.

This issue of The PhotoBook Review includes a focus on the physical production of books. The central piece offers the collected wisdom from more than a dozen book-printing professionals around the world. We broke the production process down into three digestible parts: choosing materials, preparing files for reproduction, and the experience of being on press.

As I’m writing this, I have just returned from the New York Art Book Fair, where evidence of the love of books’ form is plentiful. Examples ranged from MIT Press’s Various Small Books (a survey of photography books responding to Ed Ruscha’s small photo-conceptual artist’s books) to Aaron Canipe’s Eden, a humble, saddle-stitched book of photographs in homage and response to Robert Adams’s book of the same title. What The PhotoBook Review hopes to further and facilitate is that conversation among artists and photographers that was so abundantly evident at MoMA PS1. I hope you enjoy this issue.

—

Darius Himes is a director of Fraenkel Gallery. He was a cofounder of Radius Books and the first editor of the photo-eye Booklist, a journal dedicated to photography books. His first title, Publish Your Photography Book (Princeton Architectural Press), coauthored with Mary Virginia Swanson, will be reissued in a second edition in the spring of 2014. He lives and works in San Francisco but considers himself a global citizen.