Why Farah Al Qasimi Has Her Eye on You

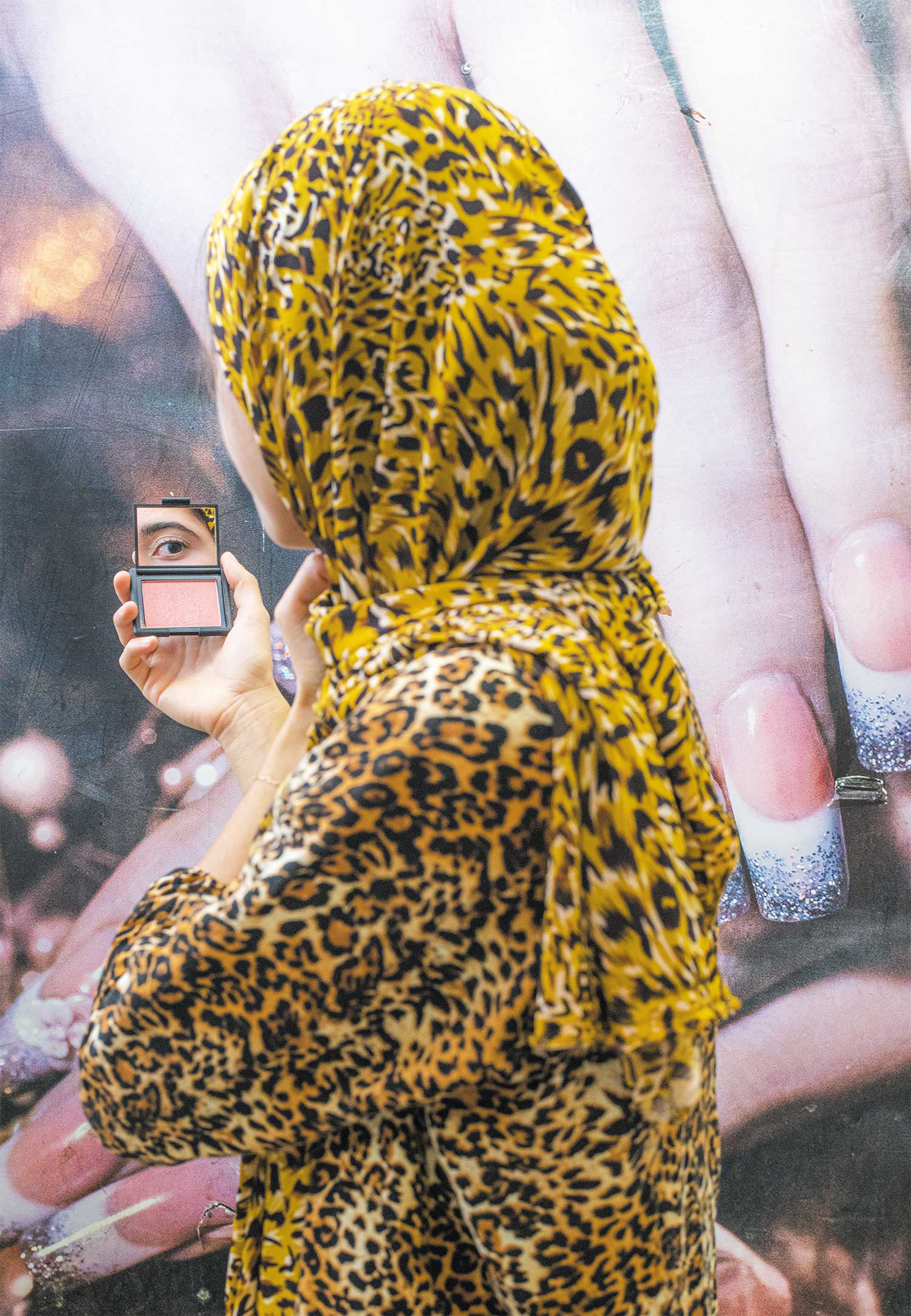

Farah Al Qasimi, Woman in Leopard Print, 2019

Courtesy the artist, Helena Anrather, New York, and The Third Line, Dubai

Courtesy the artist, Helena Anrather, New York, and The Third Line, Dubai

Farah Al Qasimi has her eye on you. In Woman in Leopard Print, one of her seventeen photographs commissioned by the Public Art Fund in 2019 and presented at one hundred bus shelters across New York’s five boroughs, a woman in said leopard print peers into a tiny compact mirror, her eyebrow superbly arched and perfectly groomed. The bold print of her headscarf is thrown into uncanny relief against a backdrop of giant yet slender fingers with glitter-tipped nails. It’s a scene of explosive beauty and humorous excess, one in which the gazes between photographer, subject, and viewer bound back and forth.

For Al Qasimi, who was raised in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, and earned her MFA from the Yale School of Art, that hall-of-mirrors choreography is central to her ideas about cultural exchange and hybridity: she’s photographed a fake “Amazon” department store in Dubai, a sparkling chandelier at a bodega in Queens, a Muslim beauty pageant in Iowa, a goat in a playhouse, and a bright blue volume of United States Treaties and Other International Agreements teetering perilously on the edge of a bookshelf.

When we spoke earlier this month, Al Qasimi, one of the most exciting young photographers working today, and a cocurator of the 2020 Aperture Summer Open, was hunkered down in rural Massachusetts, trying to make a new video piece while in isolation amidst the coronavirus crisis. Her latest solo show, Funhouse, had opened at Helena Anrather at the beginning of March, only to close a week later, along with all of New York’s other galleries; the custom orange carpeting she installed for the exhibition remains untouched—for now.

Courtesy the artist and Helena Anrather, New York

Brendan Embser: Your current exhibition, Funhouse at Helena Anrather in New York, shows your sense of curiosity about female subjects and feminine-oriented spaces, perhaps in contrast to More Good News (2017), which was more concerned with ideas about manhood and masculinity. Do you see Funhouse as a follow-up when it comes to looking at gender, or is that too simple of a comparison?

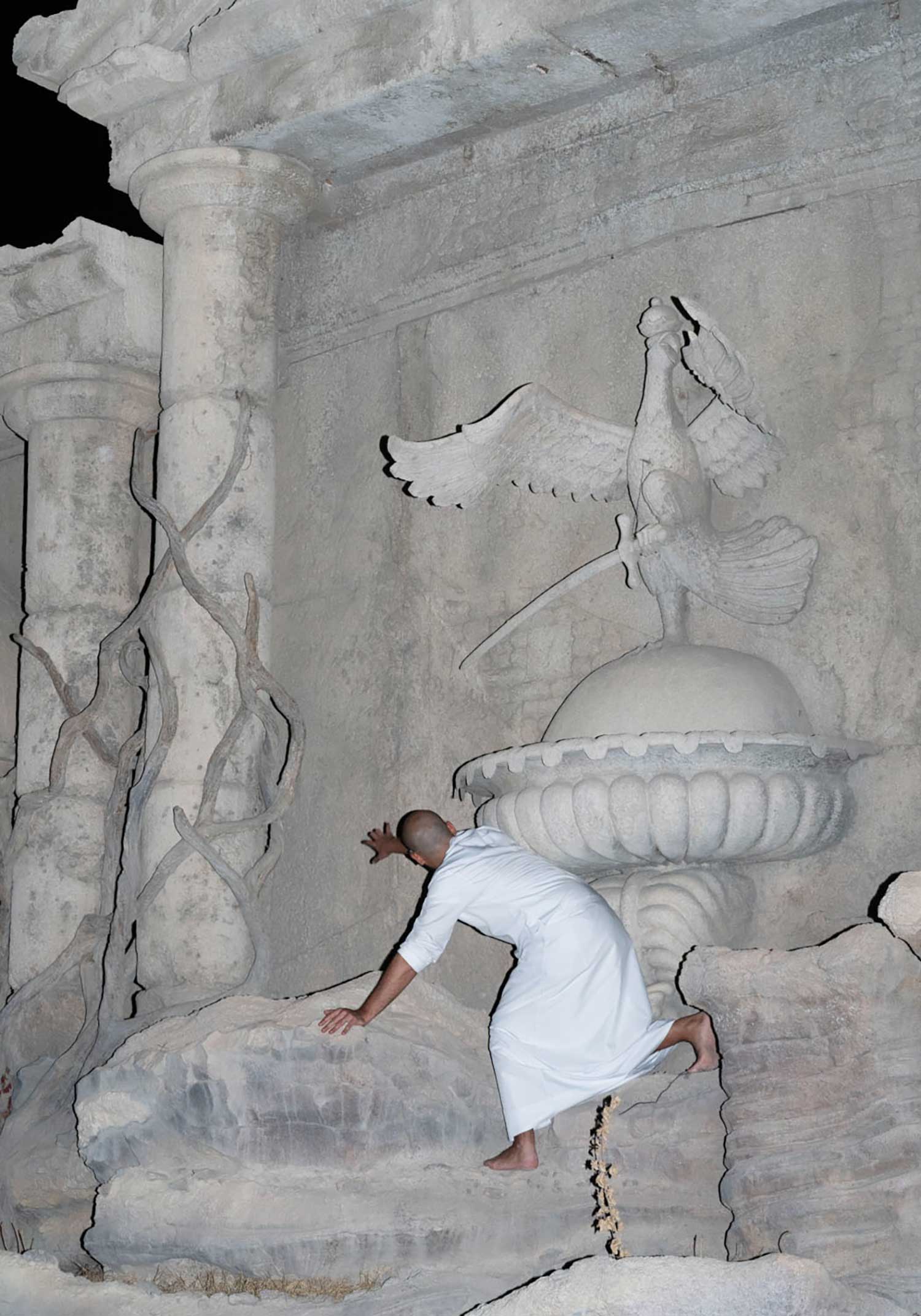

Farah Al Qasimi: I don’t see it as being so much a division by gender. But I do see that there is a similarity, in that all of the photographs have a confusing sense of location or geography that indicates that you are in a lot of in-between spaces, whether they’re immigrant communities in the U.S. or signs of colonial influence in the Middle East. There’s usually that dichotomy in the work, but I think that this particular project is more concerned with an affect. It’s more self-referential to photography as a medium that can only produce mistakes or imperfections. I compare the act of photographing something to the act of it being reflected in a funhouse mirror that warps or exaggerates reality.

Courtesy the artist and Helena Anrather, New York

Embser: What do you mean by “mistakes or imperfections”? One of the qualities that’s recognizable in your work is actually a type of perfection in the way that you build images and the quality of your printing and composition.

Al Qasimi: It’s impossible for a photograph to be truly subjective, even when we think about photojournalism and work that is primarily concerned with the act of truth-telling. There’s always a decision to leave something out of the frame. I think of “imperfection” as a replacement word for a clear lack of subjectivity. As somebody who engages with photography primarily as an artist and secondarily as a photojournalist, I’m always interested in taking creative liberties with the truth—and also in presenting a situation or an image in which people might not feel the need to ask for the truth. Maybe there’s something inherent in the image that provides information, or enough interest that you could take it at face value.

Courtesy the artist and Helena Anrather, New York

Embser: In your captions, you often don’t tell us where a picture is made. For example, The Amazon Department Store (2020), which is presented in the exhibition at life size.

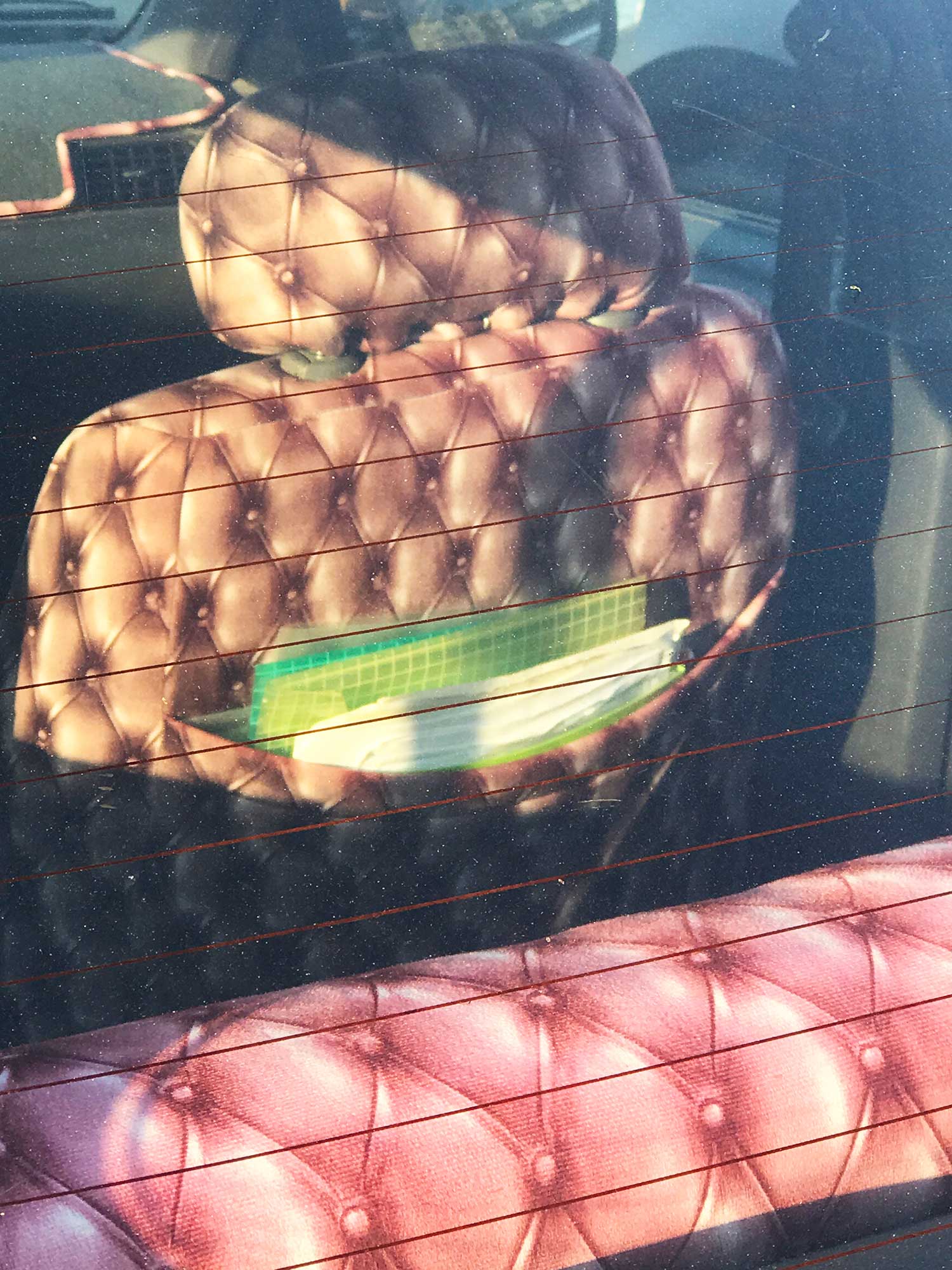

Al Qasimi: First and foremost, it’s about certain types of visibility. There are a couple of references in the show to fakes—fake surfaces that are printed to look like something else. There’s an image of a trompe l’oeil car seat that’s printed to look as though it’s tufted, but it’s not. There’s a video in which I’m wearing a copy of a clown suit from a mall that’s known for selling copies of things [Alone In A Crowd (King of Joy) (2020)]. The Amazon store is a fake Amazon, obviously. When you see it in life size, you can see there’s a tiny “the” in the corner of the sign, so it’s actually called “The Amazon.” It’s a scaled-down dollar store that’s claiming to have the same variety and low prices that the actual Amazon does. I think it’s like entering a place in which there is a real scale shift and a sense of humor about it. And also, a comedic failure in trying to transcend reality.

Courtesy the artist, Helena Anrather, New York, and The Third Line, Dubai

Embser: It plunges us into this distinct yet still inexact setting, which is compounded by the other images in the exhibition that are taken in a variety of places. “Back and forth,” as you say—and that’s the title of your commission for the Public Art Fund, Back and Forth Disco (2020), an outdoor exhibition displayed where advertisements usually appear on New York’s bus shelters. It’s one of the few exhibitions New Yorkers can actually see this spring! How did you approach this commission? When you were making the images, did you know that they’d be displayed at bus stops, and if so, did you have a sense of a different type of audience or a different way of seeing?

Al Qasimi: There was definitely a distinction. I took a very different approach to this versus making photographic work for a gallery or a book. I think part of that was just understanding how those images would function in the public landscape. I really wanted to make the photographs more celebratory than critical. I focused on small businesses in New York, many of which are run by immigrants—it started off with a desire to celebrate some of the places in my own neighborhood that I frequent as a customer. Then it grew to other neighborhoods, and I wanted to echo New York back to these people in a way that would make them feel properly represented.

Courtesy the artist, Helena Anrather, New York, and The Third Line, Dubai

Embser: The word disco—was that in your mind at the beginning, or did that come later on?

Al Qasimi: That came later. There’s a lot of color, a lot of mirrored surfaces. I think of the movement of New York as this harsh choreography of routine. We are going back and forth between places all the time on public transport, people are constantly in motion, it’s this wild frenzy of movement. Obviously, that doesn’t really apply now, but at the time it was certainly truthful to my vision of New York.

Embser: What has been your experience of seeing your work on the street or hearing about it from other people? It’s not like visiting a gallery or a museum, where you’re going to the “altar,” where there’s this agreed-upon meditation or sense of “aura.” Yet when you see an image on the street, its presence can be really interrogative, it might prompt you to be critical and self-questioning, maybe even more so than when you’re in a gallery. You’re like, What is that?

Al Qasimi: For some of the people that I’ve heard from, it’s been a surprise. They weren’t necessarily paying attention and then they saw something that echoed an advertisement, except it wasn’t really trying to sell them something. It was a photograph of something that already existed, and that was a positive thing for them to witness. I’ve also seen a few that have been graffitied—and I actually like that, because I feel like it further affirms their presence as a part of the city. I think that they’re not supposed to be these precious things that are protected by white walls. I like that people are interacting with them, even if it does “deface” the surface of the thing. A lot of the surfaces that I’m photographing have already been weathered, because they’ve been a part of the public domain for so long, and this is just an act of collaging or repurposing.

Courtesy the Public Art Fund, New York

Embser: Your photographs for the project focus on local communities and small businesses. Was it a challenge for you to do this kind of work? Going into a bodega or a shop, do you find it easy to interact with people and draw them out? Does that come easily to you?

Al Qasimi: No, it doesn’t. I’m extremely shy and I’m really wary of taking up people’s time, so it took a lot of courage to talk to people, and I had to come up with a way to efficiently explain the project so that I wasn’t bothering people if they weren’t interested. When people were interested, though, they were incredibly generous with their time.

Courtesy the artist, Helena Anrather, New York, and The Third Line, Dubai

Embser: Were there any discoveries along the way?

Al Qasimi: There was one beauty salon, Grace Beauty Salon, that I ended up at in Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, that was great. The owner had been there for a while, and it turns out that one of my good friends who grew up nearby, in Sheepshead Bay, went to this salon to get her eyebrows done as a teenager. Rubeena, the beautician and owner—her back is in one of the photographs, and she’s wearing a floral printed dress. (I actually had my eyebrows done there and she did a great job.)

Embser: I used to live in Bed-Stuy—also in Brooklyn—and there was a dry cleaner near me that was run by an elderly Korean couple. After the dry cleaner closed, that shop building reopened as a bodega, and it was fully renovated and tricked out with chandeliers. I called my dad, and I was like, “Dad, my bodega has a chandelier!” The guys who worked there were so proud of how they had redecorated the place. My dad was like, “That’s New York. That’s just what happens.”

Al Qasimi: Totally. This is your business, this is where you spend most of your time, and it’s also the way that you represent yourself to the world. It’s beautiful when somebody takes pride in that and attempts to make people feel welcome with their sense of aesthetic.

Courtesy the artist, Helena Anrather, New York, and The Third Line, Dubai

Embser: You have a color palette that’s increasingly recognizable as yours. The “Farah Al Qasimi” look. It’s a lot of light greens and pinks and blues. I had a sense about this from both More Good News and Funhouse, but it really hit me when I saw your photograph Bird Market (The Blue One Escaped)(2019)—all those colors are in one image. Then I began to see it more in your images of staircases, bedspreads, the gold ball gown in the beauty pageant. How did you develop your photographic sensibility when it comes to ideas of beauty and surface?

Al Qasimi: I grew up in the United Arab Emirates, a place that was still being developed in the 1990s and early 2000s, but there was also a lag in taste, where people were designing buildings in the style of ten years earlier. There’s also a real appreciation of the old that still exists in some pockets of the country, despite its rapid growth. At the same time, it’s a place that privileges maximalist aesthetics over minimalism, the Brooklyn-esque, the faux industrial. So, my work reflects the world that surrounded me as a young person. It’s really hard to shake. It’s funny, even with the Public Art Fund photographs, so many people are like, “Are those really all in New York?” And they are absolutely all in New York. I think it’s just that we all respond to things that feel familiar to us.

Courtesy the artist and Helena Anrather, New York

Embser: When you said the work for the Public Art Fund commission was less “critical,” what do you mean by that?

Al Qasimi: When I say “critical,” I mean it’s embedded in a sense of humor. Certainly, the Amazon image is a bit more critical in that way. With the Public Art Fund work, I really wanted the images to be much more quickly legible than other photographs. People are moving very fast, they don’t have a lot of attention to give, and I’m very conscious of how much space I want to take up in their daily lives, when they’re already being bombarded by so much imagery that’s asking them to do something, buy something, sign up for something, or call Cellino & Barnes or whatever. I think that the photographs do have a certain undercurrent of humor, but I think it’s more of a loving humor than a dark humor.

Courtesy the artist and Helena Anrather, New York

Embser: Whereas in your exhibition, to take the example of Beige Bathroom (2020)—this might not have played in the same way if it was at a bus stop. In a gallery, it becomes an object of complete fascination. The surfaces are so exacting; there’s perfect, even lighting across everything. It almost looks like a Thomas Demand construction. Then the toilet paper hanging down is the punctum, this uncanny detail. When you’re working in these private spaces, how do you achieve the perfection of the surfaces?

Al Qasimi: You know, what’s crazy is that I didn’t make any changes to that bathroom— that’s our bathroom at our house in the Emirates. It has looked that way since the house was built in the early nineties. I love that from a distance, it looks so great photographed; I think there’s something about the evenness of the light that transforms it. But when you look closer, you can see that a lot of the taps have started to rust green, because the water where we live has an incredibly high iron content. It’s this very pristine, undisturbed scene, but then you think about what happens in bathrooms and it starts to lose this veneer of beauty. It almost looks like a dollhouse bathroom, a bathroom that doesn’t get used. But I use it! There’s something kind of funny about that to me. I also think a lot of my work contains signifiers of class, but they’re legible in different ways depending on where you come from. In the Emirates, there are a lot of places where you can buy these maximalist designs for cheap. You can get beautiful baroque furniture from a Walmart. There’s a very different relationship to taste and class there than there is here.

Courtesy the artist and Helena Anrather, New York

Embser: The viewer brings something to these images that also depends on timing. Your Green Soap in Blue Bathroom (2020) has lately become a kind of stylish quarantine icon—and a cheerful reminder to wash your hands. Yet somehow it will outlive even this moment of fear and vigilance about hygiene; it will mean something else in one or two years.

Al Qasimi: I hope so! I’ve been photographing soaps for four or five years now. It’s sort of an ongoing joke that every show I ever do has to have soap in it. For me, soap has always been a stand-in for the body. I come from a place where we have a particularly formal relationship to bodies and visibility, and I like to photograph things that touch the naked body, as opposed to photographing a nude. Soaps have that undercurrent of intimacy and almost perversion.

Courtesy the artist and Helena Anrather, New York

Embser: You are one of the curators for the 2020 Aperture Summer Open, the theme for which was inspired by an exhibition presented by MoMA fifty years ago called Information. The remit for that show was a global survey of young artists, with “information” being the through line for organizing disparate projects. Kynaston McShine, the curator, noted in his catalogue essay that young people around the world, no matter if they’re in Brazil or Argentina or the U.S., may face some kind of political violence every day, regardless of whether or not their country is at war. He wrote, “It may seem too inappropriate, if not absurd, to get up in the morning, walk into a room, and apply dabs of paint from a little tube to a square of canvas. What can you as a young artist do that seems relevant and meaningful?” As a curator who is also an image-maker, what are you interested in seeing from the Aperture Summer Open?

Al Qasimi: I really appreciate work with a sense of curiosity and purpose. I don’t know what that looks like, but I know that you know it when you see it. One of the best things about photography is that we all have the same raw materials available to us, but it’s a matter of how we transform those materials. It’s really about how we see the world and how we engage with it. We’re inundated with imagery so often that I think it sometimes feels like the most eye-grabbing thing will make the most successful image. But there has to be something at stake, there has to be something that is being said beyond the act of making an intriguing image. What happens after the intrigue fades? What are you actually saying with your photographs? What are you bringing to the world that is particularly of your own mind and nobody else’s? I think that’s what I’m excited about seeing.

Courtesy the artist and Helena Anrather, New York

Embser: Finally, do you think it’s going to be harder as an artist now, in this moment, and in the coming years? What advice would you give photographers out there to stay the course?

Al Qasimi: We should continue because we have to. With relationship to “information,” artists form so much how we see the world and how we connect with one another. They teach us so much, they teach me so much. It is really important to maintain that curiosity, to keep the lines of communication open. Obviously, things will change with these extenuating circumstances. I haven’t made any art for a while. I’m trying—I was trying to make this dumb video piece on my cell phone before you called me, and it’s going terribly. But I’m trying to do it with what I have available to me, because it’s how I reckon with the world. And there are days when I can’t, because I’m too busy dealing with taxes, or emails, figuring out how to finance my studio rent for the next couple of months, or doing lectures so I can make a little bit of money here and there. But when I have a moment to breathe, I do it because I have to, because it’s the only thing that I know how to do, and that keeps me going, and that gives me a fighting chance of understanding anything about the world. If anybody else feels that urgency, then I think it’s imperative that they find a balance: being kind to themselves and meeting their basic needs, but also leaving space every so often when they’re able to practice.

Funhouse opened on March 5, 2020, at Helena Anrather, New York. See the gallery’s website for updates during the coronavirus crisis. Farah Al Qasimi: Back and Forth Disco is on extended view through June 14, 2020, in public spaces throughout New York City’s five boroughs.

The 2020 Aperture Summer Open is accepting applications through April 29, 2020. See here for details.