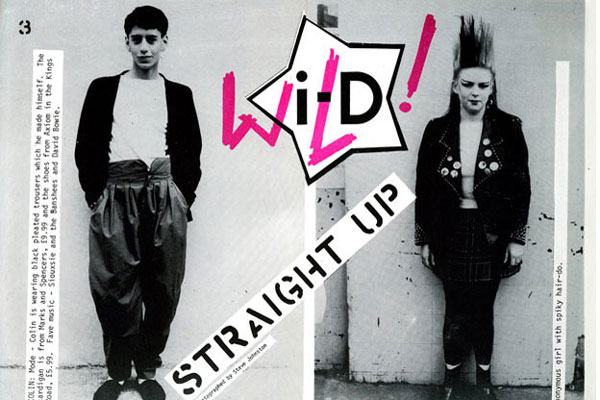

Spread from i-D, no. 1, August 1980, “Straight-Up,” with photographs by Steven Johnston

The year 1980 saw the birth in London of The Face and i-D, two independently published and quintessentially British magazines. i-D was the invention of former British Vogue art director Terry Jones, and The Face was created by former NME (New Musical Express) editor Nick Logan. These new publications signaled a bold, catalytic moment in magazine publishing, offering an escape from the constraints of mainstream media for their founders and a platform for instinctive self-expression for their contributors.

As the last vestiges of punk waned and transitioned to New Wave and then New Romantic, the first issue of The Face was produced and launched by Logan using his personal savings, and i-D’s early landscape-format issues (with silk-screened graphic covers) were designed and distributed in small runs in keeping with punk’s DIY mantra and post-punk aesthetic. Both magazines covered similar facets of youth culture; however, given the respective backgrounds of their founders, it was unsurprising that from the outset The Face was music focused, while i-D was more interested in fashion.

The first issues of i-D introduced the “Straight-Up”—formal full-length street portraits photographed against blank urban walls—that documented the personal and individual style of British youth. While many of the photographers responsible for those early images remain as little known as the majority of the passing strangers they documented, the names of other early contributors would become more familiar. As i-D’s format rotated from landscape to portrait, Nick Knight made its first “photographic” cover, featuring Sade, and Marc Lebon made the second, featuring Madonna.

Both photographers would become i-D regulars, integral to the magazine’s evolution. Lebon’s work was raw and visceral, an experimental mash-up, fashion photography without boundaries. Knight’s tireless creative contribution—one of his stories, art-directed by Marc Ascoli, was aptly titled “In Pursuit of Excellence”—was as inspiring as it was pivotal. For the magazine’s fifth anniversary issue, Knight created a series of one hundred portraits, a styled topology of Britain’s rich history of tribal youth culture, signaling the photographer’s constant inventive hunger; he continued to produce dozens of fashion stories, more often than not made with his trusted collaborator, stylist Simon Foxton. Along with the contributions of stylists Judy Blame, Caroline Baker, and Ray Petri, these and other stories over the next halfdecade augmented and magnified street style, taking the magazine to another level.

Spread from The Face no. 26, November 1990, “Back to Life,” with photographs by David Sims and styling by Melanie Ward

Spread from i-D, no. 83, August 1990, “Romania—Paradise Lost?,” with photographs by Juergen Teller and styling by Venetia Scott

Spread from i-D, no. 110, November 1992, “Like Brother Like Sister: A Fashion Story,” with photographs and styling by Wolfgang Tillmans

Spread from i-D, no. 39, August 1986, “Pose!,” with photographs by Nick Knight and styling by Simon Foxton

The early issues of The Face inherently touched on style in their portrayals of musicians, but the magazine’s fashion coverage was, at least in its formative issues, less overt. While the irreverent i-D embodied the spirit of its logo—a wink and a smile—The Face took a more classical approach to cool. As the publication found its audience and confidence, the experimental graphics and custom typography of designer Neville Brody defined the magazine’s identity, framed its content, and spread its influence.

As the publication moved beyond its music roots, it took more risks. The Face chose “style” over “fashion,” and stylist Helen Roberts initiated the magazine’s evolution with photographer Jamie Morgan. Other stylists followed—Joe McKenna, Michael Roberts, Caroline Baker, and Debbie Mason among them—but none would have the impact or lasting influence of Ray Petri, or “Sting Ray,” as he first chose to be credited. Petri was the godfather and unquestionably the leader of the creative West London “Buffalo” collective, a group of photographers (including Jamie Morgan and Marc Lebon), stylists (including Mitzi Lorenz), musicians (Neneh Cherry, Nick Kamen), artists (Barry Kamen), and models (including a fourteenyear-old Naomi Campbell), who brashly defined the look of ’80s youth culture.

Petri made the MA-1 bomber jacket ubiquitous and mixed secondhand clothes and Army surplus, skiwear, sportswear, and accessories to create a brave new world of street style, urban cowboys, rude boys and ragamuffins, men in boxer shorts, collaged gangsters, and even men in skirts. He made the radical desirable and the outrageous believable, until his career was cut short when he died in August 1989 of AIDS. His legacy would include his later work with photographer Norman Watson for Arena, but it was his original vision and idiosyncratic styling, photographed by Jamie Morgan, that provided The Face with its first “style” cover—a photograph that publisher Nick Logan would later describe as a “fuck-off image from another planet”—and some of the magazine’s most memorable stories, iconic covers, and “Killer” images. “New,” “Hard,” “Bold,” the cover lines rang out; “Buffalo: The Harder They Come the Better,” one portfolio’s introductory text announced.

While Petri reimagined British style, the short-lived Jill magazine in Paris, under the direction of stylist Elisabeth “Babeth” Dijan, also embraced liberty, and the spirit of the new. As French as i-D and The Face were British, the independently published Jill was more fashion-centric but no less influential. The magazine was alternately at times a little softer and romantic, and at times a little darker and fantastic than its English counterparts. In its short run of eleven issues, published between 1983 and 1985, Dijan’s inspired vision and styling and the photography of her contributors, including Peter Lindbergh, Jean-Baptiste Mondino, Jean-François Lepage, and a young Ellen von Unwerth, embraced the work of Jean Paul Gaultier and his generation of young French designers who turned the fashion world’s attention once more firmly back to Paris.

Spread from The Face, no. 32, May 1991, “Slapheads,” with photographs by Corinne Day and styling by Melanie Ward

Spread from i-D, no. 88, January 1991, “Teenage Precinct Shoppers,” with photographs by Nigel Shafran and styling by Melanie Ward

Cover of i-D, no. 1, August 1980, with design by Terry Jones

A year after Jill folded, Dijan’s distinctive styling was featured in a special Paris issue of The Face. By the end of the ’80s Dijan had contributed a series of highly stylized fashion stories to the magazine, including the twenty-six-page comic-bookinspired opus, “Fashion Heroes,” with photographer Stephane Sednaoui. The story featured designers Jean Paul Gaultier, Thierry Mugler, Martine Sitbon, Vivienne Westwood, Azzedine Alaïa, and a fantastical, intricately collaged series of images that preempted the digital era.

As the decade turned, a new generation of photographers, including David Sims and Corinne Day, and stylists, including Melanie Ward, emerged. Both Knight as photo editor at i-D and I as art director at The Face, nurtured and published their work. Inspired by rave music and, later, “grunge,” the pared-down photographs related more to personal style and self expression than to manufactured fantasy for commercial ends.

The images that appeared in The Face and i-D at the time were an antidote to fashion’s high glamour and excess. In the summer of 1990, The Face ran an eight-page black-and-white story featuring a sixteen-yearold, then-unknown model, Kate Moss, and put her on the cover. The antithesis of the supermodel, the thin and refreshingly natural Moss stood just five-foot-seven. Photographed by Corinne Day and styled by Melanie Ward at England’s Camber Sands beach, in feather headdress, Birkenstocks, cheesecloth, and daisy chains, Moss challenged the prevalent concept of beauty and, in doing so, embodied a new attitude and spirit for the age.

Simultaneously, David Sims further challenged mainstream ideals and archetypes, photographing a story for The Face in 1990 that featured a lank-haired, unlikely “model” named Rev against a stark white studio background. Styled by Ward and choreographed by Sims, Rev looked like a gypsy, clad in his own ill-fitting secondhand pinstripes and knitwear, as he alternately floated, posed, and cut a graphic figure. In another key 1990 story that ran in i-D, stylist Venetia Scott and photographer Juergen Teller traveled across Romania, dressing and photographing real people of various ages they encountered to produce a wonderfully nuanced, understated, and ultimately unfashionable fashion story. And, recalling and refining the simple approach of i-D’s early “Straight-Ups,” Nigel Shafran in 1991 photographed the personal style of “Teenage Precinct Shoppers” unadorned.

Spread from The Face, no. 22, July 1990, “The Daisy Age,” with Photographs by Corinne Day; styling by Melanie Ward

Pages from The Face no. 59, March 1985, “The Harder They Come,” with photographs by Jamie Morgan and styling by Ray Petri

Spread from Jill no. 8, February 1985, “Je suis snob” (I’m a snob), with photographs by J.-J. Castres and art direction by Mitzi Lorenz

Covers of Jill, no. 7 (left), and Jill, no. 10

These photographs, especially those by Day and Sims, made waves. A startled fashion world—unable to comprehend the casting, styling, or aesthetic—was at first caustic and dismissive. But the work could not be ignored. It was exciting, new, and challenging. Eventually the contagious individual visions of nonconformity made an impact on the mainstream and became a fashionable way of photographing fashion.

Both i-D and The Face continued their creative celebration of intuition, instinct, and individuality; Wolfgang Tillmans emerged through the pages of i-D in 1992 to blur and break down the boundaries between art and fashion photography, and The Face published pioneering stories by Inez & Vinoodh in 1994 and Elaine Constantine in 1997, before eventually folding in 2004. But despite both magazines’ years of commercial and cultural success, the spirit of originality and global influence that defined their work in the late ’80s and early ’90s would never be surpassed.

This article originally appeared in Aperture, issue 214, “Fashion.”