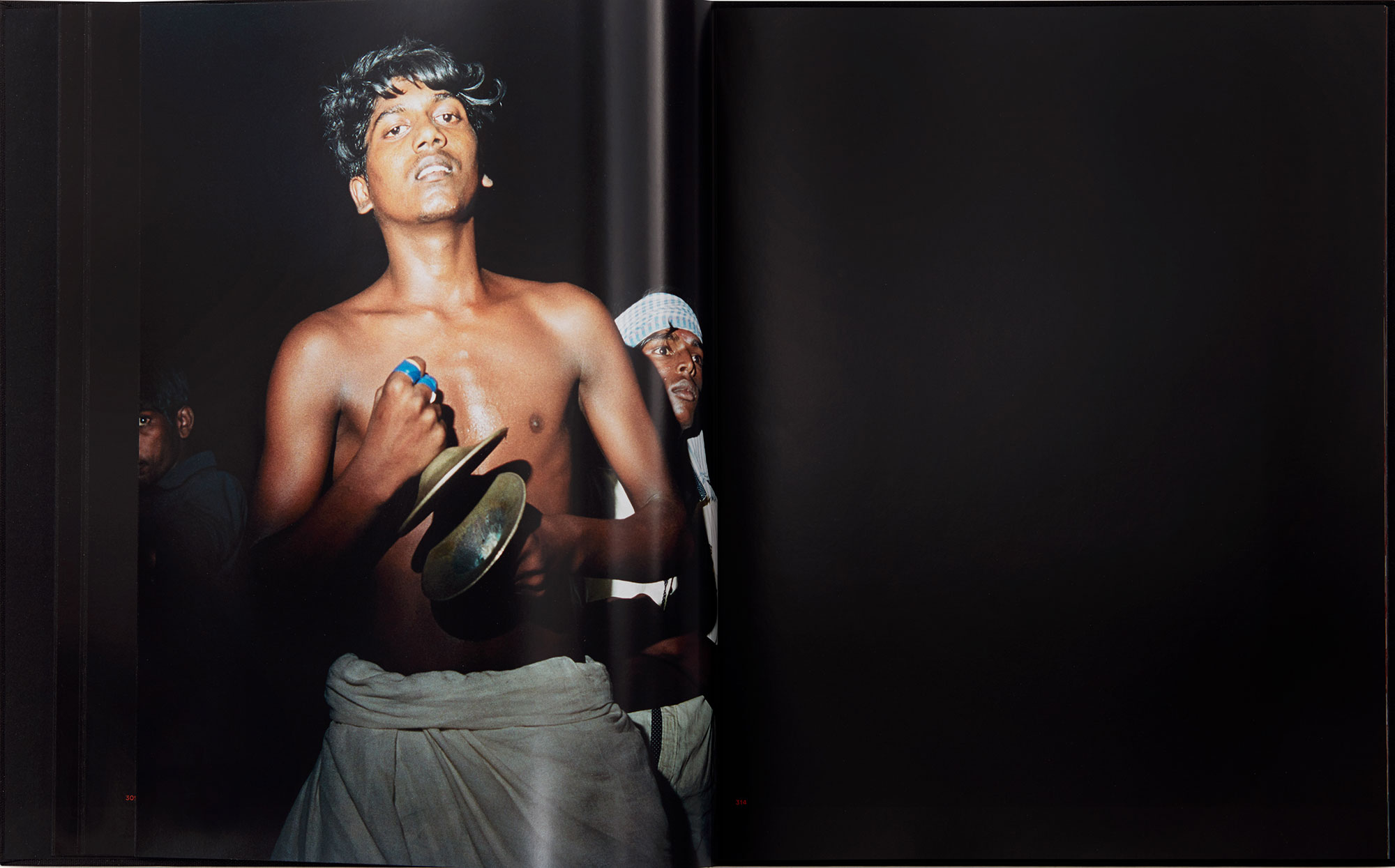

Vasantha Yogananthan, Rama Praying For Victory, Kulasekharapatnam, Tamil Nadu, India, 2019

Vasantha Yogananthan trails the horizon of counterparts, the thin line of contact between allegory and anecdote, forethought and spontaneity, the end and the beginning. In his eight-year photography project A Myth of Two Souls, the French photographer of half Sri Lankan descent retraces the Ramayana through contemporary India and Sri Lanka, evoking each chapter of the ancient Indian epic through an exploration of the daily and the eternal of both local life and myth. Across a range of cities and ever-evolving techniques, including hand-painting and mixed media, Yogananthan’s first five books—Early Times (2016), The Promise (2017), Exile (2017), Dandaka (2018), and Howling Winds (2019)—transpose the journey of the exiled Prince Rama, which reaches its apex with the great war between Rama and the evil Ravana in Yogananthan’s newest installment, Afterlife (2020).

In chapter six, Yogananthan takes us to the modern-day Dussehra festival, an annual Hindu autumnal rite celebrating Rama’s victory over evil. Yogananthan’s images from night-long attempts to reach trance and transcendence are coupled with a text adaptation by the lyrically outspoken Indian author Meena Kandasamy, whose poem becomes the footpath on the seam of nighttime: “Walk with me as we walk past ourselves.”

I spoke with Yogananthan over Skype on the cusp of the new year about the episodic night vision of this unique chapter, where gravity is reversed, eyelids never fully meet, the body glides outside of its own lines, and darkness shines the way.

Yelena Moskovich: When did you first encounter the story of the Ramayana?

Vasantha Yogananthan: I read a comic-book version when I was a kid. My dad used to have them at home. But then, I completely forgot about it for many years, until I traveled to India in 2013. I was looking for a story that would allow me to explore India and Sri Lanka, as well as photography as a medium and the space between documentary and fiction. The Ramayana was just the perfect fit. Although it’s an Indian story and very specific to South Asia, the main events could have taken place in an epic from the West. There’s a prince and a princess, the princess is abducted, and there’s a big war. You don’t need to be particularly versed in Indian mythology to relate to the feelings in the story. It brings up questions about family and love, the concept of purity, relationships, things that could speak to anyone.

Moskovich: For this chapter, the darkest of the story, what drew you to choose the Dussehra festival as your visual landscape?

Yogananthan: This was the most challenging chapter, because I had to find a visual response to war. I knew from the start that I was not going to witness any real-life battles, so the festival was a really good way for me to enter the story. Before I experienced the festival, I had imagined it more like a carnival. But when I did the first trip to Rajasthan, then the subsequent trips to the south, I saw there was a very different vibe. Most people were staying up till daylight, sometimes getting really drunk, not eating or sleeping, men dressing as women, painting their faces in black or blue, trying to reach this state of trance. War can be photographed or documented, like in photojournalism, but there’s a visual response to war that can be, not at a physical level, but rather in the mind.

Moskovich: This is so telling of our modern sense of war, actually. We aren’t necessarily going to be exposed to a battlefield, but we all know the terrain of psychological or internal struggle.

Yogananthan: Absolutely. And the thing is, no one goes to war alone. War is a collective experience. This is what was so striking for me in the festival, how all these people express this struggle with their bodies—without fighting each other. You have to imagine thousands and thousands of people. In the photos in the book, you don’t necessarily see that, because I made the choice of using the flash to have this black background where the figure stands out over the darkness.

Moskovich: Darkness is an experience in itself in Afterlife. The utter black backgrounds you describe, or even the sequence of images that are punctuated with these glossy pages of pure or near-pure blackout.

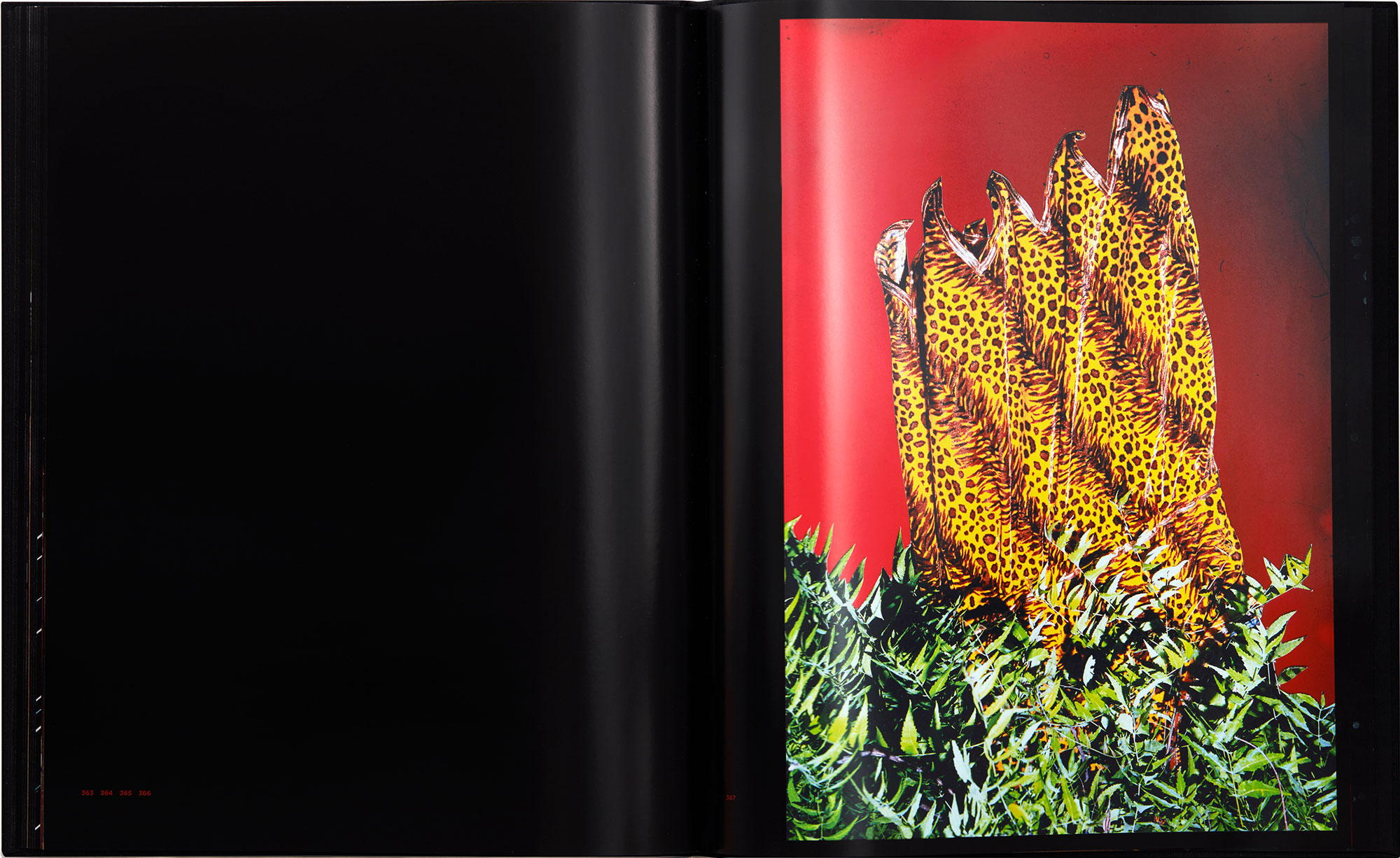

Yogananthan: Well, book number six of the Ramayana is known as the “Black Book.” Integrating the void that someone can’t help but feel when they face the darkness was very important. At some points, I wanted there to be almost nothing to look at but black. It’s really the relationship of the reader with this void that becomes the thing that’s happening.

Moskovich: There’s quite a shift in density and color palette in general in this book from your earlier work.

Yogananthan: Yes, my natural color palette is very soft, pastel colors. It’s true that this book is drastically different than the previous ones. This part of the story, the war, was calling for a more vivid palette, higher saturation, deep reds, deep blues, deep black. It was the first time I shot with a flash, which made for harsher photos with stark contrast.

Moskovich: The images you gather from the festival are uncanny, but not for the reasons one would expect. Dussehra is so full of “photogenic” rituals, so to speak—carrying clay statues of certain gods or goddesses to be dissolved in the water, or the burning of effigies of Ravana (the symbolic evil), yet you’ve sidestepped the depiction of fanfare to take us into the energy of the experience.

Yogananthan: These festivals have been so widely photographed. The idea, for me, was to use the space of the festival not to show what was happening, but what emotions were happening. What the people were feeling. For example, the last night of the festival, they burn the big Ravana statues in the middle of the night. Visually, it’s a very powerful sight. I took so many pictures of them burning Ravana, but in the end, I didn’t use a single photo of this moment in the book, because I didn’t want to fall into illustration.

Moskovich: The burning comes across in other ways. The one that stuck out for me was the couple of shots where a person is entering the sea, and the water is splashing in midair as if bursting into flames. The surprising alchemy of the sea on fire.

Yogananthan: It’s funny, because I didn’t notice that the water is always going upward. But yes, when the people are going into the sea, we see the water up in the air, we don’t know if it’s falling or rising—and the people themselves, we don’t know if they are falling or rising.

Moskovich: Throughout the book as a whole, there’s an otherworldly gravity at play. Can you tell me a little more about the distinct movement of this chapter of your project?

Yogananthan: I shot most of the previous chapters with a large-format camera, in a slow process, where everything was carefully framed and constructed over many one- or two-month trips. For Afterlife, each festival was only a few nights, so I had a very tight time frame. I was often in the middle of a crowd of thousands, and there was no room or time to look into the viewfinder. Everything was in movement. I was holding the camera with the flash and shooting in complete blindness. We don’t often speak about the physicality of photography. As a photographer, your body, how you relate to the landscape and the people, how close you get to the people, especially in portraits, it’s a very physical experience. I was using a 50 mm lens, so if I wanted to get up close, like a crop shot, I had to almost get in the face of the person.

Moskovich: The eyes in these portraits are so fascinating. Many are half-open or just barely closed, almost stuck between two realms. Or else, the iris is stretched to the very corner of the eye, as if sliding into a different consciousness.

Yogananthan: I’m really glad that you noticed that. In a way, these are the kinds of photos a photographer would generally dismiss, because you either shoot someone with their eyes open or closed. Even the shots with the most direct eye contact are disorientating. One of the strongest ones for me in the book is where we don’t really know if it’s a man or a girl, but they’re washing their face and wiping it with a piece of fabric that covers one eye, and with the other, they look directly at us.

Moskovich: It almost implicates us into their experience of the trance. Looking in to look out, a way of pulling out of their bodies. You emphasize this pursuit of dislocation by introducing collage work into the project with this book. Was that method envisioned from the beginning?

Yogananthan: The collage part was a discovery for me. When I got back from the second trip, I laid out the prints, and I could see so many of them had something in the background that didn’t work. I decided to start cutting things out of the prints and gluing them together, then scanning the collage. This was quite a revelation. It allowed me to mix the physical space of the festival in various cities—the pictures I shot in Kota with the ones I shot in Tamil Nadu, for example—and create a third space. If you look closely, you can see the trace of the cutter. Also, the different sizes of the pages layered with each other, so that you can turn one smaller page and it reveals the full photo underneath it. There was a lot more work put into the editing and sequencing of this book than any of my other ones. I’ve come to realize that studio practice is as important as being in the field and research prior to travel.

Moskovich: What brought you to invest so heavily in studio work this time around?

Yogananthan: Afterlife was shot in ten, twelve days, but put together over many months. When I started developing the photos and putting them together for the book, the pandemic hit and France went into lockdown. All the assignments and projects for photographers were canceled. I was by myself, confined at home, going to the studio every day, just facing myself, my work, what I could do, what I could not do.

Moskovich: That really speaks to, not only our global situation, but the Ramayana as well, the journey of confronting oneself.

I’d like to talk about the text in this book, which is another sort of confrontation. You’ve collaborated with various contemporary authors for the text in these chapters. What made you think of Meena Kandasamy, an Indian poet, fiction writer, and activist who’s quite emotionally courageous on the topic of intimacy, to render this chapter’s adaptation?

Yogananthan: Meena’s strength as a feminist, a woman, and a storyteller really made sense for this chapter. She received the pdf of the book and had carte blanche. You know, with this sort of collaboration, some writers want me to explain the photos or my process. But Meena didn’t ask one single question. She just emotionally responded to the photos.

The original epic has a patriarchal perspective, the princess waiting to be saved. In Meena’s poem, she twists the epic in an unusual and disturbing way. It becomes a long walk into the night and into the darkness of the soul, where the princess, Sita, is the one leading the way, walking with Ravana, who abducted her.

Moskovich: Both the text and images complement each other’s sensuality.

Yogananthan: Yes, there is sensuality in the photos, these bodies, painted or half-naked, on the black background. But there was also a specific sensuality to the festivals.

In India, men are more comfortable with their bodies and with closeness. The festival would happen in these small villages where there weren’t enough accommodations for the thousands of people who came, so come nighttime, many would sleep outside, together in the street. And when it was cold, the men would sort of cuddle each other, so at like three or four in the morning, you’d be walking over all these bodies in the street hugging each other. It was very powerful to see.

Moskovich: It’s interesting that in this book, it’s a woman’s voice narrating images of mainly men’s bodies. We’re so used to seeing women’s bodies being narrated by a man’s voice.

Yogananthan: It’s like a woman in the darkness, on the battlefield, and she’s the one taking you through, from the first page to the last.

All photographs © the artist

Moskovich: The last line of Meena’s poem, “Walk with me until it is time to walk away,” is an eerie sort of promise. Till forever and only now. It’s so resonant with the treatment of time in this book, one night between mortality and the everlasting.

Yogananthan: I wanted to find a way to condense time, so that the book can feel like just one night, one single, very long walk from light to darkness, and perhaps back to light again—but it’s very open at the end. You don’t really know if you are finally getting out of the darkness and walking toward the light, or if the darkness will be there always. The end of the chapter is really terrifying. Though Rama rescues Sita, it isn’t just a typical happy ending. They are together again, but they will never be together again.

Moskovich: This long walk is also about walking with the contradictions.

Yogananthan: Yes, the whole walk is asking this big question: what, if anything, comes after?

Vasantha Yogananthan’s Afterlife was published by Chose Commune in September 2020.