The Fine Art of Making Things

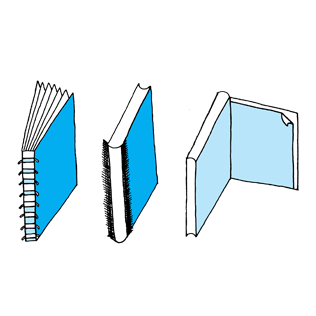

For the moment, the photobook is definitively a physical object. Somewhere, somehow—whether printed and bound at a Chinese printer whose main business is cereal boxes or output on a bedroom ink-jet printer and hand-stitched by the artist— images need to be put on paper, collated together, and made available in multiple copies. A book must be produced.

“Production” is the final stage in the long, at-times heart-wrenching process of bookmaking. And it is often where the rubber hits the proverbial road—will the delicate palette and tonal range of the original images survive the translation into a limited set of inks applied to paper via cylinders, rubber blankets, or other necessarily reductive, infinitely repeatable means? Will the paper soak up too much ink or too little? Will some innovative binding solution turn out to be a disaster? There are so many variables and so much pressure at the end of what is often a lengthy exercise of conceptualizing a book, sequencing and re-sequencing, designing and redesigning.

The production process itself can be broken down into several stages, each of which will impact the final result. We’ve spoken with a handful of people who have collectively (and many, individually) spent decades working with artists to help manifest, in physical form, the ideal book that is in their imaginations. For ease of discussion, three micro-stages have been identified: the consideration of materials, preparation of files, and what happens (or goes wrong) on press, when the images are finally made real.

—Darius Himes and Lesley A. Martin

Part A: Material Considerations

Choosing paper, endpages, trim size, boards, and inks

What are the critical production elements you feel can make or break a book?

Xavier Barral (Éditions Xavier Barral): What I believe makes a book is the reaction it provokes when, taken together, the subject, materials (primarily paper and ink), and binding bring sensuality, accuracy, and strangeness to the object.

David Strettel (Dashwood Books): Unlike a lot of publishers or book dealers, I sell contempo- rary photography books of a wide range of prices and production quality—from masterfully crafted limited editions bound in leather with tipped-in pages to zines that are folded, black- and-white, Xeroxed, and stapled. So I might be more forgiving about production issues than most. My main criteria in assessing books or zines is simply how they intrigue me and convey a sense of the artist’s passion.

Matthew Harvey (Aperture): Making a book is a bit like playing a game of chess: every move you make will impact the decisions that need to be made down the road. Everything is a continual buildup to the final moment of printing, and the only way to prepare is to try to think through everything that could possibly happen on press or in the bindery. There is a consider- able amount of planning, organizing, and preparing files that has to be done to be sure the final outcome is how we expect it, but the truth is that you only really know what the book is going to be when it’s on press, when the ink is down on paper, and the physical object is starting to take shape.

What is your approach, and what are the important considerations, when choosing materials, paper, designers, or binding materials?

Sue Medlicott (The Production Department): As a production professional there are many masters to serve, but first and foremost we are driven by budgets. We are always looking for ways to maximize clients’ available resources and still “buy” the best production possible. Fortunately we have many resources and vendors worldwide and can generally put together a combination of print production and materials that suits the client. It’s one upside of a global economy. Preparation of the illustration files for the separator is the crucial first step. Sec- ondly, it is imperative that the printer can work with the separator to make certain the images are accurately rendered on press. If the reproductions “fail,” then no amount of fancy paper, complex bindery add-ons, or press techniques can make up for this. We make picture books; everything should be geared toward telling the visual story.

Paul Schiek (TBW Books): I always consider budget and materials first. I find a structure that fits the budget and work backwards. It’s a simple form-follows-function approach. I always keep in mind factories and working-class aesthetics when producing a book, because they are inspiring to me. I try to imagine new ways of using old or outdated material. The Japanese philosophy of wabi sabi is very important to my approach. And, most importantly, I touch ev- ery material I use. I want to feel it and smell it and see what happens when it’s deconstructed. If it’s crumpled or turned inside-out, is it more interesting? Such things excite me.

Barral: There is never a systematic approach; I never have a preconceived idea in terms of materials. The starting point is my encounter with the subject and my discussion with artists and authors on what we would like to convey. From these ideas, the complex choices of materials come along. They are also nourished by my discoveries at the moment of amazing materials. Bookmaking is not an exact science. There is always a gap between what one projects onto a book and what the book conveys at the end. It is a success when the end result exceeds what one imagined and it is a failure if it is the opposite. For Martin Parr’s limited-edition Life’s a Beach, I tried several mock-ups. I would always recall my holiday photo albums when look- ing at Parr’s beach images; I felt like we shared the same memories. I was thrilled when he accepted my proposal of what I believed would be an astonishing object—including individu- ally tipped-in images and album style interleafing vellum pages. Each book brings its own particular stories.

Strettel: I recently published a book of the old pool-riding skateboard photographs of Craig Fineman. My brief for graphic designer Francesca Grassi was to depart from other pool-skating books that dwell on athleticism and are basically sports photography books aimed at skate enthusiasts. I wanted something that felt more like an artist’s book, that relied on the film-like repetition of images. The designer greatly exceeded my expectations by seeing the ballet of the skaters as Robert Longo’s drawings in the Men in the Cities series. She used a satin paper stock with very open, low-contrast scans that reproduced the empty pools as something akin to pencil drawings. Coupled with the photographs printed on yellow uncoated endpapers, the design and choice of materials immediately took the subject matter to another place.

What are the biggest difficulties or blind spots for photographers when it comes to materials, printing, and binding?

Barral: The first is that photographers often don’t think of the book as another medium, different from a portfolio of prints, with infinite possibilities in terms of paper and ink. It’s important to understand that the mental construction of a photobook is similar to one of a movie. To me, each series of photographs implies a sequence, a rhythm that builds the author’s discourse. Some photographers have specific ideas in terms of sequencing, others don’t.

Tricia Gabriel (The Ice Plant): The artist needs to know a little about how they want their book to feel or look. They should find examples of other books or papers they like, and show them to a printer or designer. They should ask questions about how to achieve that look. And if the response is, “It’s not possible,” ask why so you learn more. The problem may be simple to resolve: perhaps your print run is too small to use that type of paper, or there could be a technical reason why you can’t do something. Some knowledge of production is helpful for artists; however, a good printer should tell you when something’s not going to work.

Medlicott: I think that photographers can get too wrapped up in packaging their work with elaborate bindings or expensive materials that do not necessarily contribute to the book as a whole. It’s easy to get distracted by other books. It’s wonderful to see the infinite variety of approaches to bookmaking, but they can often misinform one about how best to present one’s own work. I’m always up for a production challenge, but after thirty years I hope that I’ve finally learned to “just say no”—or, better still, to offer up alternatives that solve the design or print problem without risking failure.

›› Continue to Part B: Preparing Files/Separations

—

Contributors include: Xavier Barral, Publisher and designer, Éditions Xavier Barral, Paris; Alexa Becker, Acquisitions editor, Kehrer Verlag, Heidelberg, Germany; Danny Frank, Project director, Meridian Printing, East Greenwich, R.I.; Tricia Gabriel, Publisher, The Ice Plant, Los Angeles; Matthew Harvey, Production manager, Aperture, New York; Kimi Himeno, Publisher, AKAAKA, Tokyo; Nicole Katz, Cofounder, Paper Chase Press, Los Angeles; Christina Labey, Cofounder, Conveyor Arts, Hoboken, N.J.; Michael Mack, Publisher, MACK Books, London; Sue Medlicott, Founder, The Production Department, Whately, Mass.; Thomas Palmer, Separator, New Haven, Conn.; Paul Schiek, Photographer and publisher, TBW Books, Oakland, Calif.; David Skolkin, Cofounder, Skolkin + Chickey Design and Radius Books, Santa Fe, N.Mex.; David Strettel, Owner and publisher, Dashwood Books, New York