Segregation Story at Salon 94

A new exhibition at Salon 94 in New York brings to light Gordon Parks’s long-lost photographs from a breakthrough 1956 Life photoessay.

Gordon Parks, Mr. and Mrs. Albert Thornton, Mobile, Alabama, 1956 © The Gordon Parks Foundation and courtesy Salon 94, New York

When it comes to matters of race in the United States, our society’s capacity to confront the darkest moments of history can be limited. There’s a perilous tendency to imagine that the injustices of the past live far behind us, beyond the reach of a pervasive postracial rhetoric that clouds our ability to remember honestly—and collectively. Gordon Parks’s Segregation Story, on view through December 20 at Salon 94 Freemans in New York, is an arresting portrait of the consequences of racism in the South, in the distinctive manner that has always defined Parks’s photojournalism.

Installation view of Gordon Parks: Segregation Story at Salon 94 Freemans, New York

The twenty-three photographs that comprise the show were originally part of a 1956 photo essay published by Life magazine entitled “The Restraints: Open and Hidden,” which profiled the lives of members of an intergenerational, extended family in Mobile, Alabama. In its first iteration, Parks’s series was accompanied by a story by the journalist Robert Wallace. The original images were long thought to be lost. But, in 2012, archivists at the Gordon Parks Foundation discovered a box of color slides related to “The Restraints,” from which the prints for this exhibition were made. They remain startlingly potent. Unlike most images of the segregated South and the Civil Rights Movement, which were printed in black and white, “The Restraints: Open and Hidden” featured color photographs—a departure in editorial policy for Life, at the time one of the most visible influential news magazines.

Installation view of Gordon Parks: Segregation Story at Salon 94 Freemans, New York

The risks surrounding the assignment were considerable. Parks was dispatched to the place he once referred to as “the motherland of racism” with the specific intention of exposing the ills of white supremacy. And his role as a photojournalist did not prevent him from experiencing the very fear that many of his subjects faced on a daily basis. That Parks had the ability, through photography, to center on the voices of the South’s most vulnerable only increased the anger of the white community in Mobile. In an attempt to ensure his safety, Life enlisted Sam Yette, a Mobile native, to guide Parks throughout the duration of his stay. There was, however, no guide to protect Parks’s subjects who, despite viewing their participation in “The Restraints” as an important act of resistance, had to contend with job loss and other forms of harassment in the wake of publication.

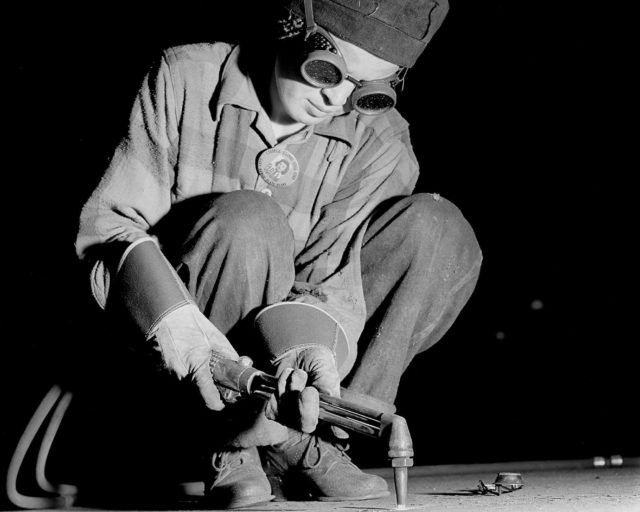

Gordon Parks, Department Store, Mobile, Alabama, 1956 © The Gordon Parks Foundation and courtesy Salon 94, New York

Segregation Story poignantly chronicles black life in the face of stark subjugation from which we are but a mere three generations removed. It’s precisely this fact—this not so recent past—that lends the exhibition its gravitas. The show begins with an untitled photograph of an advertisement for a plot of land and as one walks clockwise throughout the gallery, one moves from images of the playground to images of the bedroom. It is an exhibition that takes care to frame the public and the private as active sites of struggle.

Gordon Parks, At Segregated Drinking Fountain, Mobile, Alabama, 1956 © The Gordon Parks Foundation and courtesy Salon 94, New York

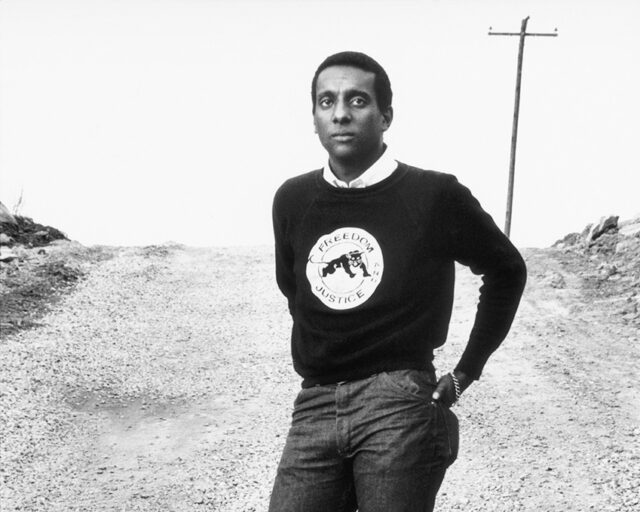

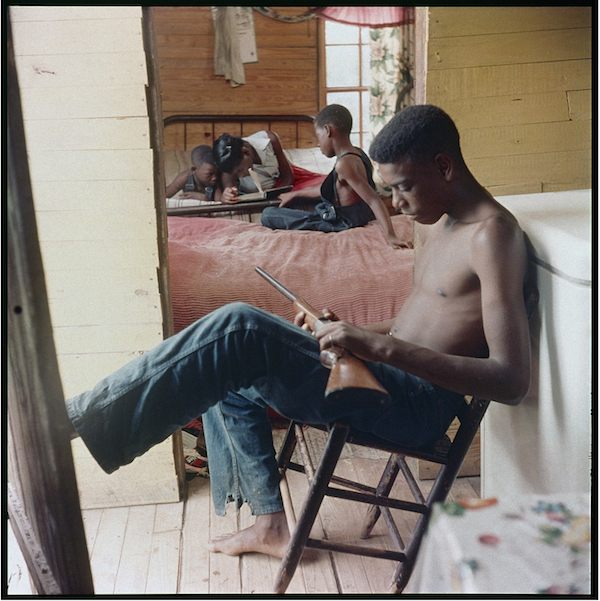

In At Segregated Drinking Fountain, Mobile, Alabama (1956), Parks captures three young girls and a man who is presumably their father drinking from a “Coloreds Only” water fountain as two young women off to the side look on. In Department Store, Mobile, Alabama (1956), Joanne Wilson and her niece stand stoically beneath the “Colored Entrance” sign at the local movie theater. Parks’s portrait, Mr. and Mrs. Albert Thorton, Mobile, Alabama (1956) is an image replete with grace and eloquence, capturing the couple as they stare directly into the camera. Meanwhile, the world outside rages and the threat of violence is palpable for blacks in the South, as seen in the portrait of Willie Causey Jr. fumbling with a shotgun in Willie Causey Jr., with Gun During Violence in Alabama (1956).

Gordon Parks, Willie Causey Jr., with Gun During Violence in Alabama, Shady Grove, Alabama, 1956 © The Gordon Parks Foundation and courtesy Salon 94, New York

Though Salon 94 is primarily dedicated to contemporary artists, Parks’s exhibition at the gallery comes at a timely moment. In 2015 alone, several institutions revisited Parks’s work, including the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and The High Museum of Art in Atlanta. (The High Museum recently co-published, with Steidl, a new monograph of Segregation Story, with essays by Charlayne Hunter-Gault and Maurice Berger.) As the U.S. finds itself in the throes of a cultural moment where young people of color are aggressively utilizing photography, video, and new media to shine a light on continued black violence at the hands of the state, it seems only right to see this renewed focus on Parks’s legacy as a bridge between the past and the present.

Installation view of Gordon Parks: Segregation Story at Salon 94 Freemans, New York. All installation views courtesy Salon 94.

Three years after the tragic 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama, two years after the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Plessy v. Ferguson, and one year after the Montgomery bus boycotts, “The Restraints: Open and Hidden” offered a nuanced glimpse of black life in the midst of Jim Crow South. Now, nearly six decades later, these photographs humanize the narrative of racial injustice, just as they did in 1956. The political is simultaneously deeply personal.

Segregation Story is on view through December 20.